Security and Environmental Variables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administering Unidata on UNIX Platforms

C:\Program Files\Adobe\FrameMaker8\UniData 7.2\7.2rebranded\ADMINUNIX\ADMINUNIXTITLE.fm March 5, 2010 1:34 pm Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta UniData Administering UniData on UNIX Platforms UDT-720-ADMU-1 C:\Program Files\Adobe\FrameMaker8\UniData 7.2\7.2rebranded\ADMINUNIX\ADMINUNIXTITLE.fm March 5, 2010 1:34 pm Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Notices Edition Publication date: July, 2008 Book number: UDT-720-ADMU-1 Product version: UniData 7.2 Copyright © Rocket Software, Inc. 1988-2010. All Rights Reserved. Trademarks The following trademarks appear in this publication: Trademark Trademark Owner Rocket Software™ Rocket Software, Inc. Dynamic Connect® Rocket Software, Inc. RedBack® Rocket Software, Inc. SystemBuilder™ Rocket Software, Inc. UniData® Rocket Software, Inc. UniVerse™ Rocket Software, Inc. U2™ Rocket Software, Inc. U2.NET™ Rocket Software, Inc. U2 Web Development Environment™ Rocket Software, Inc. wIntegrate® Rocket Software, Inc. Microsoft® .NET Microsoft Corporation Microsoft® Office Excel®, Outlook®, Word Microsoft Corporation Windows® Microsoft Corporation Windows® 7 Microsoft Corporation Windows Vista® Microsoft Corporation Java™ and all Java-based trademarks and logos Sun Microsystems, Inc. UNIX® X/Open Company Limited ii SB/XA Getting Started The above trademarks are property of the specified companies in the United States, other countries, or both. All other products or services mentioned in this document may be covered by the trademarks, service marks, or product names as designated by the companies who own or market them. License agreement This software and the associated documentation are proprietary and confidential to Rocket Software, Inc., are furnished under license, and may be used and copied only in accordance with the terms of such license and with the inclusion of the copyright notice. -

The Disappearance of Lake Chad: History of a Myth

The disappearance of Lake Chad: history of a myth Géraud Magrin1 Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, France Abstract The article explores the hydropolitics of Lake Chad. Scientific and popular views on the fate of Lake Chad differ widely. The supposed 'disappearance' of the Lake through water abstraction and climate change is a popular myth that endures because it serves a large set of heterogeneous interests, including those supporting inter-basin water transfers. Meanwhile scientific investigations show substantial and continuing Lake level fluctuations over time, and do not support its projected disappearance. The task is to understand how the myth of the disappearing Lake has been engendered and used, by studying the discourses and the strategies of the main stakeholders involved. The Lake has been protected so far from massive water abstraction, and inter-basin transfer projects, due to the fragmentation of its political management, new security threats, and the piecemeal nature of the interests in play. Key words: Lake Chad; environmental myths; hydropolitics; political ecology; inter-basin transfers Résumé Cet article aborde le lac Tchad d’un point de vue hydropolitique. Les discours scientifique et du grand public sur l'état du lac Tchad diffèrent largement. La « disparition » supposée du lac sous l’effet des prélèvements anthropiques pour l’irrigation et du changement climatique est un mythe qui perdure car il sert un ensemble d'intérêts hétérogènes, dont ceux favorables à un projet de transfert d'eau inter-bassins. Or les recherches scientifiques montrent que le lac a toujours fluctué au cours du temps, et que les dynamiques récentes ne conduisent pas à sa disparition, si souvent annoncée. -

2021 Girls Spring Season

2021 GIRLS' SPRING PROGRAM SEASON INFORMATION PACKET LAST UPDATED: WEDNESDAY, APRIL 7TH @ 10:00PM 2020-21 RETURN TO PLAY - MAKING YOUR SAFETY A PRIORITY C R E A T E D B Y V C U N I T E D S T A F F U S I N G R E S T O R E I L L I N O I S A N D J V A / U S A V / A A U V O L L E Y B A L L G U I D E L I N E S 2021 SPRING TRYOUTS 2020-21 Seaon - Return To Play - Making Your Safety Our Priority GET READY FOR THE 2021 SPRING SEASON WHY TRYOUTS? Even though we anticipate that the Pre-TRryouEt Cl-iniTcs aRre a gYreatO way Uto prTepar eC for tLhe uIpNcomiIngC club season early sessions will be in-house leagues, or simply keep your skills sharp during the year. Each session will focus on a we need to accomplish two goals with range of skills and include drills to sharpen your overall game and build our tryouts. First, to create a competitive training environment with your confidence as you prepare for the spring club season. players of similar ability and objectives. Second, is to be in a position to quickly U17 U16 U15 move to teams/tournament play when SATURDAY, APRIL 17 SATURDAY, APRIL 17 SATURDAY, APRIL 17 Illinois determines it is safe to do so. 9A-11A OR 1P-3P 9A-11A OR 1P-3P 9A-11A OR 1P-3P COST: $30 COST: $30 COST: $30 AGE GROUPS USA Volleyball and AAU Volleyball have U14 U13 U12-U11 changed the birthdate cutoff starting SATURDAY, APRIL 17 SATURDAY, APRIL 17 SATURDAY, APRIL 17 with the upcoming season. -

Increasing Day-Length Induces Spring Flushing of Tropical Dry Forest Trees in the Absence of Rain

Trees (2002) 16:445–456 DOI 10.1007/s00468-002-0185-3 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Guillermo Rivera · Stephen Elliott · Linda S. Caldas Guillermo Nicolossi · Vera T. R. Coradin Rolf Borchert Increasing day-length induces spring flushing of tropical dry forest trees in the absence of rain Received: 10 September 2001 / Accepted: 26 March 2002 / Published online: 20 July 2002 © Springer-Verlag 2002 Abstract In many conspecific trees of >50 species high- synthetic gain in tropical forests with a relatively short ly synchronous bud break with low inter-annual varia- growing season. tion was observed during the late dry season, around the spring equinox, in semideciduous tropical forests of Keywords Bud break · Phenology · Photoperiodic Argentina, Costa Rica, Java and Thailand and in tropical control · Tropical semideciduous forests savannas of Central Brazil. Bud break was 6 months out of phase between the northern and southern hemispheres and started about 1 month earlier in the subtropics than Introduction at lower latitudes. These observations indicate that “spring flushing”, i.e., synchronous bud break around the In cold-temperate forests, vegetative phenology of all spring equinox and weeks before the first rains of the broad-leaved trees is strongly synchronized by winter wet season, is induced by an increase in photoperiod of cold. In contrast, severe seasonal drought does not syn- 30 min or less. Spring flushing is common in semidecid- chronize vegetative phenology in tropical semideciduous uous forests characterized by a 4–6 month dry season forests with a dry season of 4–6 months and annual rain- and annual rainfall of 800–1,500 mm, but rare in neo- fall between 800 and 1,500 mm. -

Red Hat Jboss Data Grid 7.2 Data Grid for Openshift

Red Hat JBoss Data Grid 7.2 Data Grid for OpenShift Developing and deploying Red Hat JBoss Data Grid for OpenShift Last Updated: 2019-06-10 Red Hat JBoss Data Grid 7.2 Data Grid for OpenShift Developing and deploying Red Hat JBoss Data Grid for OpenShift Legal Notice Copyright © 2019 Red Hat, Inc. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ . In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, the Red Hat logo, JBoss, OpenShift, Fedora, the Infinity logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Linux ® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java ® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS ® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL ® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. Node.js ® is an official trademark of Joyent. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

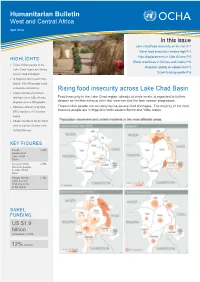

Rising Food Insecurity Across Lake Chad Basin Humanitarian Bulletin

Humanitarian Bulletin West and Central Africa April 2016 In this issue Lake Chad food insecurity on the rise P.1 Sahel food insecurity remains high P.3 New displacements in Côte d’Ivoire P.5 HIGHLIGHTS Ebola resurfaces in Guinea and Liberia P.6 Three million people in the Regional update on epidemics P.7 Lake Chad region are facing Sahel funding update P.8 severe food shortages. In Nigeria’s Borno and Yobe states, 800,000 people need immediate assistance. Rising food insecurity across Lake Chad Basin Clashes between herders and farmers in Côte d’Ivoire Food insecurity in the Lake Chad region, already at crisis levels, is expected to further deepen as families exhaust their last reserves and the lean season progresses. displace over 6,000 people. Between January and April, Three million people are currently facing severe food shortages. The majority of the food insecure people are in Nigeria’s north-eastern Borno and Yobe states. DRC reports 5,757 cholera cases. Ebola resurfaces for the third time in Liberia, Guinea sees its first flare-up. KEY FIGURES People 2.4M displaced in Lake Chad Basin Severely food 2.9M insecure people in Lake Chad Basin People facing 6.7M crisis level of food insecurity in the Sahel SAHEL FUNDING US $1.9 billion requested in 2016 12% funded Humanitarian Bulletin | 2 In Borno, 1.6 million Immediate emergency assistance required people are in emergency According to a joint UN multi-sectoral assessment, carried out in April, in Borno alone, some 1.6 million people are facing severe food insecurity, with more than 550,000 in phase of food insecurity. -

Palynological Evidence for Gradual Vegetation and Climate Changes During the African Humid Period Termination at 13◦ N from a Mega-Lake Chad Sedimentary Sequence

Clim. Past, 9, 223–241, 2013 www.clim-past.net/9/223/2013/ Climate doi:10.5194/cp-9-223-2013 of the Past © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Palynological evidence for gradual vegetation and climate changes during the African Humid Period termination at 13◦ N from a Mega-Lake Chad sedimentary sequence P. G. C. Amaral1, A. Vincens1, J. Guiot1, G. Buchet1, P. Deschamps1, J.-C. Doumnang2, and F. Sylvestre1 1CEREGE, Aix-Marseille Universite,´ CNRS, IRD, College` de France, Europoleˆ Mediterran´ een´ de l’Arbois, BP 80, 13545 Aix-en-Provence cedex 4, France 2Departement´ des Sciences de la Terre, Universite´ de N’Djamena (UNDT) BP 1027 N’Djamena, Chad Correspondence to: P. G. C. Amaral ([email protected]) Received: 16 May 2012 – Published in Clim. Past Discuss.: 18 June 2012 Revised: 18 December 2012 – Accepted: 19 December 2012 – Published: 29 January 2013 Abstract. Located at the transition between the Saharan and period. However, we cannot rule out that an increase of Sahelian zones, at the center of one of the largest endorheic the Chari–Logone inputs into the Mega-Lake Chad might basins, Lake Chad is ideally located to record regional envi- have also contributed to control the abundance of these taxa. ronmental changes that occurred in the past. However, until Changes in the structure and floristic composition of the veg- now, no Holocene archive was directly cored in this lake. etation towards more open and drier formations occurred In this paper, we present pollen data from the first sed- after ca. 6050 cal yr BP, following a decrease in mean Pann imentary sequence collected in Lake Chad (13◦ N; 14◦ E; estimates to approximately 600 (−230/+600) mm. -

The Variability of Lake Chad : Hydrological Modelling and Ecosystem Services

The variability of Lake Chad : hydrological modelling and ecosystem services 1 1 2 Jacques Lemoalle Jean-Claude Bader Marc Leblanc (1) IRD/MSE, UMR G-Eau, BP 64501, 34394 Montpellier Cx5, France Corresponding address : [email protected] (2) School of Earth and Environmental Sci., James Cook University, Cairns, Australia Abstract As in most of West and Central Africa, the rainfall regime over the Lake Chad basin has changed around 1970 from a humid to a dry period. This rainfall change is the cause of the changes in Lake Chad area. Lake Chad being a closed lake, its surface area has changed according to the lower water inputs from the watershed. The lake, which covered about 22000 km2 in the 1960s, is now divided into different individual seasonal or perennial lake basins. In the northern basin of the lake, the seasonally inundated area has varied from zero in dry years (as in 1985, 1987) to about 6000 km2 (1979, 1989 and 1999-2001). In the southern basin of the lake, the between year variability has markedly decreased. The changes in lake area and in the links between the lake basins have been modelled as a function of the river inputs. Satellite estimates of water area in the northern basin and gauge levels in the southern basin have been used as calibration data. The water volumes incorporated in and lost by the sediments during the annual wet and dry cycle have been taken into account in the model. The hydrologic changes are the driving forces for the natural resources associated with the lake i.e. -

Spring Winter Summer Autumn

• Always drive on good, properly inflated issouri is a state of four seasons tires. and each season has its own unique road conditions. Missouri driving • Know and obey all traffic laws. cannot be categorized entirely into spring, summer, autumn, or winter. Nature some- • Be ready to adjust your speed to be ap- times mixes our four seasons together, and propriate for constantly changing driving this can cause problems when we travel. conditions. This brochure has been prepared to give you some tips on how to handle our Finally, let’s all work together, so fewer many varied driving conditions. people will become traffic crash statistics on Missouri’s highways. Spring Buckle Up Missouri! • Never drive when you have been drink- ing alcoholic beverages. Summer • Never ride with someone who has been drinking. • If medication directions indicate you should not drive after taking it, don’t do Feel free to call the it. Road Condition Report Hotline at: Produced by: Public Information and Education Division • Have a good attitude when you drive. Be Published by: Autumn patient with others. 1-888-275-6636 Missouri State Highway Patrol 1510 East Elm Street • Give driving your full attention. Behind Or, check the Patrol’s Jefferson City, MO 65101 the wheel is no place to read, put on 573-751-3313 makeup, or talk on the cell phone. web site at: V/TDD 573-751-3313 email: [email protected] • How about those eyes? Don’t be vain. If www.mshp.dps.mo.gov www.mshp.dps.mo.gov Winter you need glasses, wear them. -

Lake Chad: Recent Dry Season Area Changes, Near Term Dry Season Area Projections, and Dry Season Area Projections Through the Year 2100

LAKE CHAD: RECENT DRY SEASON AREA CHANGES, NEAR TERM DRY SEASON AREA PROJECTIONS, AND DRY SEASON AREA PROJECTIONS THROUGH THE YEAR 2100 by Frederick S. Policelli A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland December, 2018 © 2018 Frederick S. Policelli All Rights Reserved Lake Chad, in the Sahel region of Africa is shallow, freshwater, and the terminal lake of an enormous (2.5 million km2) endorheic basin. The lake has exhibited a wide range of area over the centuries. More recently, some of the earliest satellite photographs of Lake Chad were taken in the 1960s when the lake area was estimated to be about 25,000 km2. During the late 1960s, the 1970s and the 1980s, a recurrent set of droughts caused the lake area to decrease sharply. During the period when the lake was drying, large areas of aquatic vegetation formed in the lake, while a small area of open water persisted. It appears likely that some researchers and the popular press have focused only on the small open water area when reporting the size of Lake Chad, because it is very challenging to detect and measure the area of flooded vegetation. Reports of a decrease of ninety to ninety-five percent of lake area, relative to lake area in the 1960s, led the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) to study an interbasin water transfer from the Ubangi River, a tributary to the Congo River. The motivation for this dissertation was to use satellite data and modeling results to provide information on the recent trends of total Lake Chad area (open water and flooded vegetation), and to provide statistical models and results for near term and long term modeling of the lake area. -

Adaptive Water Management in the Lake Chad Basin Addressing Current Challenges and Adapting to Future Needs

Seminar Proceedings Adaptive Water Management in the Lake Chad Basin Addressing current challenges and adapting to future needs World Water Week, Stockholm, August 16-22, 2009 Adaptive Water Management in the Lake Chad Basin Addressing current challenges and adapting to future needs World Water Week, Stockholm, August 16-22, 2009 Contents Acknowledgements 4 Seminar Overview 5 The Project for Water Transfer from Oubangui to Lake Chad 9 The Application of Climate Adaptation Systems and Improvement of 19 Predictability Systems in the Lake Chad Basin The Aquifer Recharge and Storage Systems to Halt the High Level of Evapotranspiration 29 Appraisal and Up-Scaling of Water Conservation and Small-Scale Agriculture Technologies 45 Summary and Conclusions 59 4 Adaptive Water Management in the Lake Chad Basin Acknowledgements The authors wish to express their gratitude to the following persons for their support; namely: Claudia Casarotto for the technical revision and Edith Mahabir for editing. Thanks to their continuous support and prompt action, it was possible to meet the very narrow deadline to produce it. Seminar Overview 5 Seminar Overview Maher Salman, Technical Officer, NRL, FAO Alex Blériot Momha, Director of Information, LCBC The entire geographical basin of the Lake Chad covers 8 percent of the surface area of the African continent, shared between the countries of Algeria, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Libya, Niger, Nigeria and Sudan. In recent decades, the open water surface of Lake Chad has reduced from approximately 25 000 km2 in 1963, to less than 2 000 km2 in the 1990s heavily impacting the Basin’s economic activities and food security.