Thomas Kellein Ways of Fluxus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Byrd Musical Papers PASC-M.0064

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf687007kg No online items Finding Aid for the Joseph Byrd Musical Papers PASC-M.0064 Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 October 13. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Joseph Byrd PASC-M.0064 1 Musical Papers PASC-M.0064 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Joseph Byrd musical papers Identifier/Call Number: PASC-M.0064 Physical Description: 10.4 Linear Feet(26 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1960-1980 Abstract: Collection consists predominantly of holographs of Joseph Byrd's concert pieces, "happening" pieces, film and television music, and arrangements, with some works by other composers, papers and memorabilia. Also contains some audiotapes and videotapes. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audiovisual materials. Audiovisual materials are not currently available for access, unless otherwise noted in a Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements note at the file level. All requests to access processed digital materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. -

Chaos Theory and Robert Wilson: a Critical Analysis Of

CHAOS THEORY AND ROBERT WILSON: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF WILSON’S VISUAL ARTS AND THEATRICAL PERFORMANCES A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts Of Ohio University In partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Shahida Manzoor June 2003 © 2003 Shahida Manzoor All Rights Reserved This dissertation entitled CHAOS THEORY AND ROBERT WILSON: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF WILSON’S VISUAL ARTS AND THEATRICAL PERFORMANCES By Shahida Manzoor has been approved for for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Charles S. Buchanan Assistant Professor, School of Interdisciplinary Arts Raymond Tymas-Jones Dean, College of Fine Arts Manzoor, Shahida, Ph.D. June 2003. School of Interdisciplinary Arts Chaos Theory and Robert Wilson: A Critical Analysis of Wilson’s Visual Arts and Theatrical Performances (239) Director of Dissertation: Charles S. Buchanan This dissertation explores the formal elements of Robert Wilson’s art, with a focus on two in particular: time and space, through the methodology of Chaos Theory. Although this theory is widely practiced by physicists and mathematicians, it can be utilized with other disciplines, in this case visual arts and theater. By unfolding the complex layering of space and time in Wilson’s art, it is possible to see the hidden reality behind these artifacts. The study reveals that by applying this scientific method to the visual arts and theater, one can best understand the nonlinear and fragmented forms of Wilson's art. Moreover, the study demonstrates that time and space are Wilson's primary structuring tools and are bound together in a self-renewing process. -

The Joseph Byrd Musical Works and Papers Collection, 1960-1980

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf687007kg No online items Finding Aid for the Joseph Byrd Musical Works and Papers Collection, 1960-1980 Processed by the staff of the Dept. of Music Special Collections, UCLA; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Joseph Byrd 64 1 Musical Works and Papers Collection, 1960-1980 Finding Aid for the Joseph Byrd Musical Works and Papers Collection, 1960-1980 Collection number: 64 UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: The Staff of the Dept. of Music Special Collections, UCLA Date Completed: 1997 Encoded by: Caroline Cubé © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: The Joseph Byrd Musical Works and Papers Collection, Date (inclusive): 1960-1980 Collection number: 64 Creator: Byrd, Joseph Extent: 3 boxes (ca. 160 items). -

The Fiery Furnaces: Gallowsbird Bark Seth Kim-Cohen Rough Trade

The Fiery Furnaces: Gallowsbird Bark Seth Kim-Cohen Rough Trade An unpublished review of the Fiery Furnaces debut, 2003. ¤ ¤¤ Maybe Pierre Bourdieu is right. Maybe the “field of cultural production” is nothing but a game board and each producer, promoter, buyer and seller is a piece on the board. We each fulfill our roles. The board doesn’t change much over time. Nor do the relative roles of the pieces. The game always needs someone at the top and someone at the bottom, but it also needs someone filling the various roles in between. If Bourdieu is right, we might see the Fiery Furnaces as the contemporary occupiers of the space once held by Joseph Byrd’s the United States of America. In 1968 the United States of America grated against the outer extremities of rock music, integrating sources as diverse as 19th century folk forms, Sousa-esque brass arrangements and experimental analog electronics (Gordon Marron is credited with playing ring modulator) into an au courant blend of pastoral psychedelia, blues, and proto-acid guitar leads. With their debut, Gallowsbird’s Bark, the Fiery Furnaces chafe against the current state of the art, interpolating 19th century folk forms, dada lyrics, and splice and dice arrangements into an au courant mix of earnest sonics, postmodern cool and post-acid guitar leads. So there we have it: neatly bundled and tied in a fancy French bow. 1 But Bourdieu’s system fails to account for a few alternatives to this neat bundle. The Fiery Furnaces are Eleanor and Matthew Friedberger: brother and sister (like the White Stripes?), duo (like the White Stripes, the Kills, and Quasi), and from New York City (like you name it). -

Projetos Editoriais Que Testam Os Limites Da Publicação

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES FACULDADE DE ARQUITETURA Projetos Editoriais que testam os limites da Publicação Bárbara Forte Fernandes Gonçalves Teixeira Dissertação Mestrado em Práticas Tipográficas e Editoriais Contemporâneas Dissertação orientada pela Professora Doutora Sofia Leal Rodrigues 2019 I DECLARAÇÃO DE AUTORIA Eu, Bárbara Forte Fernandes Gonçalves Teixeira, declaro que a presente dissertação de mestrado intitulada “Projetos Editoriais que testam os limites da Edição”, é o resultado da minha investigação pessoal e independente. O conteúdo é original e todas as fontes consultadas estão devidamente mencionadas na bibliografia ou outras listagens de fontes documentais, tal como todas as citações diretas ou indiretas têm devida indicação ao longo do trabalho segundo as normas académicas. O Candidato Lisboa, 22 de Outubro de 2019 II RESUMO O livro enquanto veículo de expressão artística tem vindo a ser explorado desde a génese das práticas editoriais. O design, a música, o teatro, a literatura, o cinema, entre outras formas de manifestação criativa, são ingredientes do bolo que constituí a book art e a publicação independente, cuja expressividade é diretamente influenciada pela mistura rica de áreas e técnicas participantes. É necessário conhecer particularidades do trabalho percursor neste âmbito, para que se assimile e compreenda o papel disruptivo do artist’s book. As formas comunicação gráfica primevas (são exemplo as pinturas rupestres), despoletaram espontaneamente, cumprindo as necessidades do ser humano pré-histórico. Com o avançar dos anos, e à medida que a linguagem se desenvolvia cada vez mais complexa, os suportes de inscrição de matéria foram também aperfeiçoados. As culturas chinesa e egípcia possibilitaram a descoberta e refinamento do papel, ao aplicarem as fibras de bambu e papiro, respetivamente, num processo de fabricação de “folhas”. -

Queens Park Music Club

Alan Currall BBobob CareyCarey Grieve Grieve Brian Beadie Brian Beadie Clemens Wilhelm CDavidleme Hoylens Wilhelm DDavidavid MichaelHoyle Clarke DGavinavid MaitlandMichael Clarke GDouglasavin M aMorlanditland DEilidhoug lShortas Morland Queens Park Music Club EGayleilidh MiekleShort GHrafnhildurHalldayle Miekle órsdóttir Volume 1 : Kling Klang Jack Wrigley ó ó April 2014 HrafnhildurHalld rsd ttir JJanieack WNicollrigley Jon Burgerman Janie Nicoll Martin Herbert JMauriceon Burg Dohertyerman MMelissaartin H Canbazerbert MMichelleaurice Hannah Doherty MNeileli Clementsssa Canbaz MPennyichel Arcadele Hannah NRobeil ChurmClements PRoben nKennedyy Arcade RobRose Chu Ruanerm RoseStewart Ruane Home RobTom MasonKennedy Vernon and Burns Tom Mason Victoria Morton Stuart Home Vernon and Burns Victoria Morton Martin Herbert The Mic and Me I started publishing criticism in 1996, but I only When you are, as Walter Becker once learned how to write in a way that felt and still sang, on the balls of your ass, you need something feels like my writing in about 2002. There were to lift you and hip hop, for me, was it, even very a lot of contributing factors to this—having been mainstream rap: the vaulting self-confidence, unexpectedly bounced out of a dotcom job that had seesawing beat and herculean handclaps of previously meant I didn’t have to rely on freelancing Eminem’s armour-plated Til I Collapse, for example. for income, leaving London for a slower pace of A song like that says I am going to destroy life on the coast, and reading nonfiction writers everybody else. That’s the braggadocio that hip who taught me about voice and how to arrange hop has always thrived on, but it is laughable for a facts—but one of the main triggers, weirdly enough, critic to want to feel like that: that’s not, officially, was hip hop. -

Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

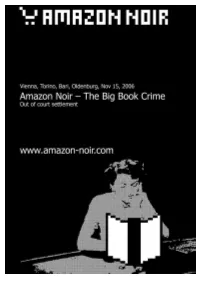

The Fluxus Reader By: Ken Friedman Edited by Ken Friedman ISBN: 0471978582 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 PART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIESPART I THREE HISTORIES Page 2 Page 3 Ben Patterson, Terry Reilly and Emmett Williams, of whose productions we will see this evening, pursue purposes already completely separate from Cage, though they have, however, a respectful affection.' After this introduction the concert itself began with a performance of Ben Patterson's Paper Piece. Two performers entered the stage from the wings carrying a large 3'x15' sheet of paper, which they then held over the heads of the front of the audience. At the same time, sounds of crumpling and tearing paper could be heard from behind the on-stage paper screen, in which a number of small holes began to appear. The piece of paper held over the audience's heads was then dropped as shreds and balls of paper were thrown over the screen and out into the audience. As the small holes grew larger, performers could be seen behind the screen. The initial two performers carried another large sheet out over the audience and from this a number of printed sheets of letter-sized paper were dumped onto the audience. On one side of these sheets was a kind of manifesto: "PURGE the world of bourgeois sickness, `intellectual', professional & commercialised culture, PURGE the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic Page 4 [...] FUSE the cadres of cultural, social & political revolutionaries into united front & action."2 The performance of Paper Piece ended as the paper screen was gradually torn to shreds, leaving a paper-strewn stage. -

Report to the U. S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2008

Report to the U.S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2008 Created by the U.S. Congress to Preserve America’s Film Heritage Created by the U.S. Congress to Preserve America’s Film Heritage April 10, 2009 Dr. James H. Billington The Librarian of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540-1000 Dear Dr. Billington: In accordance with The Library of Congress Sound Recording and Film Preservation Programs Reauthorization Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-336), I submit to the U.S. Congress the 2008 Report of the National Film Preservation Foundation. We present this Report with renewed purpose and responsibility. The NFPF awarded our first preservation grants in 1998, fueled by contributions from the entertainment industry. Since then, federal funding from the Library of Congress has redrawn the playing field and enabled 187 archives, libraries, and museums across 46 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico to save historically significant films and share them with the public. These efforts have rescued 1,420 works that might otherwise have been lost—newsreels, documentaries, silent-era features, avant-garde films, home movies, industrials, and independent works. Films preserved through the NFPF are now used widely in education and reach audiences everywhere through exhibition, television, video, and the Internet. The renewal of our federal legislation, passed unanimously by both houses of Congress in 2008, celebrates these formative steps but also recognizes that there is still much to do. With the Library’s continued support, we will strengthen efforts in the months ahead and press in new directions to advance film preservation and broaden access. -

A Festival of Unexpected New Music February 28March 1St, 2014 Sfjazz Center

SFJAZZ CENTER SFJAZZ MINDS OTHER OTHER 19 MARCH 1ST, 2014 1ST, MARCH A FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 28 FEBRUARY OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC Find Left of the Dial in print or online at sfbg.com WELCOME A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED TO OTHER MINDS 19 NEW MUSIC The 19th Other Minds Festival is 2 Message from the Executive & Artistic Director presented by Other Minds in association 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and SFJazz Center 11 Opening Night Gala 13 Concert 1 All festival concerts take place in Robert N. Miner Auditorium in the new SFJAZZ Center. 14 Concert 1 Program Notes Congratulations to Randall Kline and SFJAZZ 17 Concert 2 on the successful launch of their new home 19 Concert 2 Program Notes venue. This year, for the fi rst time, the Other Minds Festival focuses exclusively on compos- 20 Other Minds 18 Performers ers from Northern California. 26 Other Minds 18 Composers 35 About Other Minds 36 Festival Supporters 40 About The Festival This booklet © 2014 Other Minds. All rights reserved. Thanks to Adah Bakalinsky for underwriting the printing of our OM 19 program booklet. MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WELCOME TO OTHER MINDS 19 Ever since the dawn of “modern music” in the U.S., the San Francisco Bay Area has been a leading force in exploring new territory. In 1914 it was Henry Cowell leading the way with his tone clusters and strumming directly on the strings of the concert grand, then his students Lou Harrison and John Cage in the 30s with their percussion revolution, and the protégés of Robert Erickson in the Fifties with their focus on graphic scores and improvisation, and the SF Tape Music Center’s live electronic pioneers Subotnick, Oliveros, Sender, and others in the Sixties, alongside Terry Riley, Steve Reich and La Monte Young and their new minimalism. -

James Hoff and Danny Snelson

Inventory Arousal James Hoff and Danny Snelson A lecture by James Hoff at the National Academy of Art, Oslo, Norway on February 11, 2008. Transcribed in real time by Danny Snelson in Tokyo, Japan. Introduction by Danny Snelson In the winter of 2007, James Hoff contacted me to transcribe a lecture he would be giving on minor histories as primary information—or rather, on secondary information as source material for primary history—in Oslo, Norway. In the spirit of collaboration, I took this offer as an opportunity to experiment in performative editing & live data processing. The process of this transcription I undertook was simple. First, I received a large list of key figures, publications and works James might address. His lecture was improvisational, based on hundreds of images and hours of artists’ curated video running simultaneously and connected anecdotally, so there was no set agenda or instructions for the material that would or wouldn’t be used. Over the next couple of months, I googled together a massive body of text around this list (from the various virtual resources available to me online in Japan). The sources ran from book reviews to artist interviews, from essays, memoirs and stock lists to articles, blog posts and even full length books: what- ever was searchable & citable, informative or interesting. We then arranged for Børre Saethre, a Norwegian artist, to relay the lec- ture via Skype telephony to my computer in Tokyo. Taking James’ words from this digital transmission, I culled paragraphs from my previously complied text file using the “find,” “copy” & “paste” functions of my TextEdit program. -

Kevin Holm-Hudson, Ed., Progressive Rock Reconsidered (New York and London: Routledge, 2002), ISBN 0 8153 3714 0 (Hb), 0 8153 3715 9 (Pb)

twentieth century music http://journals.cambridge.org/TCM Additional services for twentieth century music: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Mark Carroll, Music and Ideology in Cold War Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), ISBN 0 521 82072 3 (hb) Stephen Walsh twentieth century music / Volume 1 / Issue 02 / September 2004, pp 308 - 314 DOI: 10.1017/S147857220525017X, Published online: 22 April 2005 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S147857220525017X How to cite this article: Stephen Walsh (2004). twentieth century music, 1, pp 308-314 doi:10.1017/S147857220525017X Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TCM, IP address: 131.251.254.13 on 25 Feb 2014 REVIEWS twentieth-century music 1/2, 285–314 © 2004 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S1478572205210174 Printed in the United Kingdom Kevin Holm-Hudson, ed., Progressive Rock Reconsidered (New York and London: Routledge, 2002), ISBN 0 8153 3714 0 (hb), 0 8153 3715 9 (pb) Three decades on from its creative zenith, so-called ‘progressive’ rock remains probably the most critically maligned and misunderstood genre in the history of rock music. During progressive rock’s heyday in 1969–77 British groups like Yes, Genesis, Emerson, Lake & Palmer (ELP), King Crimson, and Gentle Giant, along with their later North American cousins, like Kansas and Rush, sought to blur the distinction between art and popular music, crafting large-scale pieces – often in multiple ‘movements’ – in which the harmonic, metric, and formal complexities seemed to share more of a stylistic affinity with, say, a symphonic work by Liszt or Holst than with a typical three- or four-minute pop song.1 Critics at the time differed widely in their opinions of progressive rock, but most agreed that it was not ‘authentic’ rock music. -

The Message Is the Medium: the Communication Art of Yoko

..... LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS VII ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Xl INTRODUCTION I CHAPTER 1 Historical Background Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data and Common Issues Yoshimoto, Midori. 9 Into pertormance :Japanese women artists in New York / Midorl Yoshimoto. p. em. CHAPTER 2 Peiforming the Self: Includes bibliographical references and index. Yayoi Kusama and Her ISBN 0-8135-3520-4 (hardcover: alk. paper) -ISBN 0-8135-3521-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) Ever-Expanding Universe 45 1. Arts, Japanese-New York (State)-New York-20th century. 2. Pertormance art- New York (State)- New York. 3. Expatriate artists -New York (State)- New York. 4. Women artists-Japan. I. Tille. CHAPTER 3 The Message NX584.l8Y66 2005 Is the Medium: 700' .92'395607471-dc22 2004011725 The Communication Art A British Cataloging-In-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library. ifYOko Ono 79 Copyright ©2005 by Midori Yoshimoto CHAPTER 4 PlaJ1ul Spirit: All rights reserved The Interactive Art No part of this book may be reproduced or utiiized In any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permis ifTakako Saito 115 sion from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 100 Joyce Kilmer Avenue, Piscataway, NJ 08854-8099. The only exception to this prohibition is '1alr use" as defined by CHAPTER 5 Music, Art, Poetry, U.S. copyright law. and Beyond: Book design by Adam B. Bohannon The Intermedia Art ifMieko Shiomi 139 Manufactured in the United States of America The Message 79 Is the Medium: The Communication Art eifYoko Ono I realized then, that it was not enough in life to just wake up in the morning, eat, talk, walk, and go to sleep.