Official Journal C 91 of the European Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPCI À Fiscalité Propre Et Périmètre De La Loi Montagne

DEPARTEMENT DE L'ARDECHE EPCI à fiscalité propre et périmètre de la loi Montagne Limony Charnas St-Jacques- Vinzieux Périmètre de la Loi Montagne d'Atticieux Lapeyrouse-Mornay Brossainc Félines Serrières Epinouze 11 Communautés d'agglomération Savas 11 Peyraud St-Marcel- Saint-Rambert-d'Albon lès-Annonay Peaugres Bogy Saint-Sorlin-en-Valloire 2 - Bassin d'Annonay St-Clair Champagne Anneyron Boulieu- Colombier- 15 - Privas Centre Ardèche lès-Annonay le-Cardinal St-Désirat Davézieux St-Cyr Andancette Annonay St-Etienne- Chateauneuf-de-Galaure Communautés de communes de-Valoux Albon Thorrenc Villevocance 22 1 - Vivarhône Vanosc Vernosc-lès- Talencieux Fay-le-clos Roiffieux Annonay 44 Mureils 3 - Val d'Ay Andance Beausemblant 4 - Porte de DrômArdèche ( 07/26) Monestier Ardoix Vocance Quintenas Saint-Uze 5 - Pays de St-Félicien St-Alban-d'Ay Sarras Saint-Vallier Claveyson 6 - Hermitage-Tournonais (07/26) St-Julien- Vocance St-Romain-d'Ay Ozon Saint-Barthélémy-de-Vals 7 - Pays de Lamastre St-Symphorien- Eclassan de-Mahun 8 - Val'Eyrieux 33 St-Jeure-d'Ay Arras- s/RhôneServes-sur-Rhône Satillieu 9 - Pays de Vernoux Préaux Cheminas St-André- St-Pierre-s/Doux Sécheras Chantemerle-les-Blés 10 - Rhône-Crussol en-Vivarais Erome Lalouvesc Gervans Vion 11 - Entre Loire et Allier Vaudevant Larnage St-Victor 12 - Source de la Loire Etables Lemps Crozes-Hermitage St-Jean- Rochepaule Pailharès Veaunes 13 - Ardèche des Sources et Volcans 55 de-Muzols Lafarre St-Félicien Tain-l'Hermitage Mercurol 14 - Pays d'Aubenas Vals Colombier- 66 Chanos-Curson Devesset -

Part Report for Each Region Was Prepared

WORK PACKAGE 10 First Confrontation of Theory and Practice: Test of the Tools and Discussion of their Use for Sustainable Regional Development in Five (Six!) Test Regions FINAL REPORT – 9. 11. 2007 WORK PACKAGE RESPONSIBLE: Anton Melik Geographical Institute of Scientific Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts (AMGI SRC SASA) CONTENT I. Introduction II. Methodology III. Searching for sustainable regional development in the Alps: Bottom-up approach IV. Workshops in selected test regions 1. Austria - Waidhofen/Ybbs 1.1. Context analysis of the test region 1.2. Preparation of the workshop 1.2.1. The organizational aspects of the workshop 1.3. List of selected instruments 1.4. List of stakeholders 1.5. The structure of the workshop 1.5.1. Information on the selection of respected thematic fields/focuses 1.6. Questions for each part of the workshop/ for each instrument 1.7. Revised answers 1.8. Confrontation of the context analysis results with the workshop results 1.9. Starting points for the second workshop 1.10. Conclusion 2. France – Gap 2.1. Context analysis of the test region 2.2. Preparation of the workshop 2.2.1. The organizational aspects of the workshop 2.3. List of selected instruments 2.4. List of stakeholders 2.5. The structure of the workshop 2.5.1. Information on the selection of respected thematic fields/focuses 2.6. Questions for each part of the workshop/ for each instrument 2.7. Revised answers 2.8. Confrontation of the context analysis results with the workshop results 2.9. Starting points for the second workshop 2.10. -

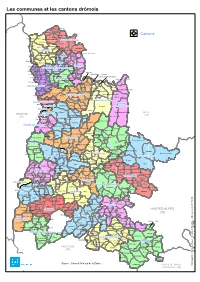

Mise En Page

Les communes et les cantons drômois Lapeyrouse-Mornay Epinouze Manthes Lens-Lestang CantonsCantons Moras-en-Valloire Saint-Rambert-d'Albon Saint-Sorlin-en-Valloire GRANDGRAND SERRESERRE (LE)(LE) Anneyron Grand-Serre Hauterives Andancette Châteauneuf-de-Galaure Albon Montrigaud Saint-Martin-d'Août STST VALLIERVALLIER Saint-Christophe-et-le-Laris Tersanne Mureils Saint-Bonnet-de-Valclérieux Saint-Avit Miribel Laveyron Motte-de-Galaure Montchenu Saint-Uze Bathernay Saint-Laurent-d'Onay Claveyson Crépol Saint-Vallier Ratières Montmiral Saint-Barthélemy-de-Vals Chalon Ponsas Charmes-sur-l'Herbasse ROMANSROMANS IIII Serves-sur-Rhône Bren Arthémonay ROMANSROMANS IIII STST DONATDONAT SURSUR L'HERBASSEL'HERBASSE Saint-Michel Marsaz Margès Geyssans Erôme Chantemerle-les-Blés Saint-Donat Parnans Eymeux Châtillon-Saint-Jean Gervans Chavannes Peyrins Saint-Nazaire-en-Royans Larnage Triors Saint-Bardoux Saint-Thomas-en-Royans Crozes-Hermitage Veaunes Génissieux Baume-d'Hostun Mercurol ROMANSROMANS II Saint-Julien-en-Vercors Clérieux Mours-Saint-Eusèbe Tain-l'Hermitage Chanos-Curson Sainte-Eulalie Romans Saint-Paul-lès-Romans Motte-Fanjas Granges-les-Beaumont Hostun TAINTAIN L'HERMITAGEL'HERMITAGE TAINTAIN L'HERMITAGEL'HERMITAGE Jaillans Echevis Rochechinard Beaumont-Monteux Beauregard-Baret Bourg-de-Péage Saint-Martin-en-Vercors Pont-de-l'Isère Saint-Jean-en-Royans Chatuzange-le-Goubet Châteauneuf-sur-Isère Saint-Laurent-en-Royans Roche-de-Glun Alixan BOURGBOURG DEDE PEAGEPEAGE Oriol-en-Royans Marches Chapelle-en-Vercors Saint-Marcel-lès-Valence Bésayes -

Hautes-Alpes En Car Lignes Du Réseau

Lignes du LER PACA N 21 NICE - DIGNE - GAP OE 29 MARSEILLE - BRIANÇON Ligne 35 du LER PACA 30 GAP-BARCELONNETTE Briançon - Grenoble 31 MARSEILLE-NICE-SISTERON-GRENOBLE LA GRAVE 35 VILLARD D’ARÉNE 33 DIGNE - VEYNES - GAP - BRIANÇON OULX S 35 BRIANÇON - GRENOBLE COL DU LA LE LAUZET NÉVACHE ITALIE 4101 GAP - GRENOBLE VIA TRANSISÈRE UTARET PLAMPINET Numéros Utiles Le Monêtier-les-Bains G1 S33 ISÈRE SERRE CHEV S33 CESANA Région LE ROSIER G (38) S32 CLAVIÈRE ◗ LER PACA : 0821 202 203 ALLIER Montgenèvre H LA VACHETTE ◗ TER : 0800 11 40 23 V LE PRÉ DE ALLÉE S31 Département MME CARLE ◗ PUY-ST PIERRE BRIANÇON 05 Voyageurs PUY-ST ANDRÉ ( Hautes-Alpes) : 04 92 502 505 AILEFROIDE Pelvoux ◗ Transisère : 0820 08 38 38 CERVIÈRES ST ANTOINE PRELLES Ligne 4101 du LER PACA F ENTRAIGUES Vallouise Intra Hautes-Alpes Gap - Grenoble S30 QUEYRIÈRES ◗ Réseau Urbain de Gap, 1800 1600 F2 ABRIÈS Puy st vincent LES VIGNEAUX S28 Linéa : 04 92 53 18 19 Brunissard ◗ FREISSINIÈRES L’ARGENTIÈRE AIGUILLES Transport Urbain de Briançon ASPRES La Chapelle CHÂTEAU (TUB) : 04 92 20 47 10 Corps LES CORPS LA-BESSÉE QUEYRAS Ristolas en Valgaudemar S26 VILLE-VIEILLE Arvieux LE COIN 4101 ST FIRMIN F1 ESTÉYÈRE MOLINES CHAUFFAYER 29 FONTGILLARDE S27 PIERRE LES COSTES 33 GROSSE S25 La Joue C2 St-Véran LA MOTTE EN CHAMPSAUR Orcières du Loup MAISON DU ROY C1 Station MONT-DAUPHIN S24 Ligne 31 du LER PACA ST-ETIENNE Ceillac CHAILLOL S12 GUILLESTRE EN DÉVOLUY St Bonnet ORCIÈRES SNCF Marseille-Nice-Sisteron-Grenoble D1 D2 SAINT-JEAN-SAINT-NICOLAS RISOUL A LA SAULCE - GAP AGNIÈRES S22 S23 -

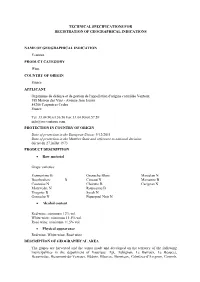

Technical Specifications for Registration of Geographical Indications

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR REGISTRATION OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS NAME OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION Ventoux PRODUCT CATEGORY Wine COUNTRY OF ORIGIN France APPLICANT Organisme de défense et de gestion de l'appellation d'origine contrôlée Ventoux 388 Maison des Vins - Avenue Jean Jaurés 84206 Carpentras Cedex France Tel. 33.04.90.63.36.50 Fax 33.04.90.60.57.59 [email protected] PROTECTION IN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN Date of protection in the European Union: 9/12/2011 Date of protection in the Member State and reference to national decision: décret du 27 juillet 1973 PRODUCT DESCRIPTION Raw material Grape varieties: Vermentino B Grenache Blanc Marselan N Bourboulenc B Cinsaut N Marsanne B Counoise N Clairette B Carignan N Mourvedre N Roussanne B Viognier B Syrah N Grenache N Piquepoul Noir N Alcohol content Red wine: minimum 12% vol. White wine: minimum 11.5% vol. Rosé wine: minimum 11.5% vol. Physical appearance Red wine, White wine, Rosé wine DESCRIPTION OF GEOGRAPHICAL AREA The grapes are harvested and the wines made and developed on the territory of the following municipalities in the department of Vaucluse: Apt, Aubignan, Le Barroux, Le Beaucet, Beaumettes, Beaumont-du-Ventoux, Bédoin, Blauvac, Bonnieux, Cabrières-d'Avignon, Caromb, Carpentras, Caseneuve, Crestet, Crillonle-Brave, Entrechaux, Flassan, Fontaine-de-Vaucluse, Gargas, Gignac, Gordes, Goult, Joucas, Lagnes, Lioux, Loriol-du-Comtat, Malaucène, Malemort- du-Comtat, Maubec, Mazan, Méthamis, Modène, Mormoiron, Murs, Pernes, Robion, La Roque- sur-Pernes, Roussillon, Rustrel, Saignon, Saumane, Saint-Didier, Saint-Hippolyte-le-Graveron, Saint-Martin-de-Castillon, Saint-Pantaléon, Saint-Pierre-de-Vassols, Saint-Saturnin-d'Apt, Venasque, Viens, Villars and Villes-sur-Auzon. -

Télécharger Annexe 12 A

ANNEXE 12a Sectorisation : Secteur de recrutement du Lycée Aristide Briand à Gap par collège et commune - rentrée 2021 Secteur du collège de La Bâtie- Secteur du CLG A. Mauzan Secteur CLG de St Bonnet Secteur CLG F.Mitterrand - Veynes Secteur CLG de Serres Secteur Clg Hauts de Plaine - Laragne Neuve code code Code Code Code Code Commune Commune Commune Commune Commune Commune postal postal postal postal postal postal GAP : voir annexes 11 a 05000 AVANCON 05230 ANCELLE 05260 AGNIERES EN DEVOLUY 05250 BRUIS 05150 ANTONAVES * 05300 et 11b - sectorisation en CHORGES 05230 ASPRES-LES-CORPS 05800 ASPREMONT 05140 CHANOUSSE 05700 BARRET-LE-BAS 05300 fonction de l'adresse LA BATIE-NEUVE 05230 BENEVENT-ET-CHARBILLAC 05500 ASPRES-SUR-BUECH 05140 L' EPINE 05700 BARRET-SUR-MEOUGE* 05300 LA BATIE-VIELLE 05000 BUISSARD 05500 CHABESTAN 05140 LA BATIE-MONTSALEON 05700 CHATEAUNEUF-DE-CHABRE * 05300 LA ROCHETTE 05000 CHABOTTES 05260 CHATEAUNEUF D'OZE 05400 LA PIARRE 05700 EOURRES * 05300 MONTGARDIN 05230 CHAMPOLEON 05250 FURMEYER 05400 LE BERSAC 05700 ETOILE SAINT-CYPRICE * 05700 PRUNIERES 05230 CHAUFFAYER 05800 LA BEAUME 05140 MEREUIL 05701 EYGUIANS * 05300 RAMBAUD 05000 FOREST-SAINT-JULIEN 05260 LA CLUSE 05250 MONTCLUS 05700 LAGRAND * 05300 ST-ETIENNE-LE-LAUS 05130 LA CHAPELLE EN VALGAUDEMAR 05800 LA FAURIE 05140 MONTJAY 05150 LARAGNE-MONTEGLIN * 05300 VALSERRES 05130 LA FARE-EN-CHAMPSAUR 05500 LA HAUTE BEAUME 05 MONTMORIN 05150 LAZER * 05300 LA MOTTE-EN-CHAMPSAUR 05500 LE SAIX 05400 MONTROND 05700 LE POET * 05300 LAYE 05500 MONTBRAND 05140 MOYDANS 05150 -

Le Mot Du Maire

N°19 - AVRIL 2017 LE MOT DU MAIRE Ce début d’année nous donne une charge de travail Sommaire : conséquente au vue des échéances électorales : présidentielles Editorial P. 1 et législatives ; nous comptons sur vous et votre sens du civisme. Droits civiques P. 2 à 4 Pour donner suite à l’agenda d’accessibilité, les premiers travaux seront envisagés pour la mairie avec regroupement des Municipalité P . 5 à 10 services « Mairie » et « Poste » dans un même lieu. Nous poursuivrons l’accessibilité par l’école. Vie du village P. 11 à 17 Malgré le début du printemps exceptionnel, le gel a frappé la Communiqué commune assez sévèrement. informations P. 18 à 19 Je vous souhaite une bonne lecture de ce bulletin rempli Festivités P.20 à 21 d’informations. Etat civil P. 22 Michel JOUVE Bloc notes P. 23 PAGE 2 LE FLASSANNAIS N°19 - AVRIL 2017 DROITS CIVIQUES RECENSEMENT MILITAIRE (ou recensement citoyen) Les jeunes gens dès le jour de leurs 16 ans sont priés de venir se faire recenser en Mairie dans le trimestre qui suit leur anniversaire. Ainsi, un jeune ayant 16 ans le 15 juin 2017 doit venir se faire recenser avant le 30 juin 2017. À la suite du recensement, la mairie délivre une attestation de recensement. Le recensement permet à l'administration de convoquer le jeune pour qu'il effectue la journée défense et citoyenneté (JDC). Le recensement permet aussi l'inscription d'office du jeune sur les listes électorales à ses 18 ans. Coordonnées téléphoniques du Bureau accueil du Centre du Service National de Nîmes : 04.66.02.31.73 Centre joignable également sur l’adresse institutionnelle : http://www.defense.gouv.fr/jdc PROCHAINES ELECTIONS Les nouvelles cartes électorales vous ont été distribuées et sont à utiliser pour le prochain scrutin. -

Oui Non Pour Les Particuliers*

Déchets verts = POUR LES PARTICULIERS* déchets issus de tontes de gazon, * y compris dans le cas où le particulier confie les travaux PREFETE DES HAUTES-ALPES des feuilles et aiguilles mortes, à une entreprise spécialisée des tailles d'arbres et d'arbustes LE BRULAGE DES DECHETS VERTS DANS LES HAUTES-ALPES Afin de préserver la qualité de l’air, le brûlage DES DÉCHETS VERTS EST INTERDIT SUR L'ENSEMBLE DU DÉPARTEMENT des Hautes-Alpes. Toutefois, des dérogations existent, le brûlage des déchets verts issus de débroussaillement obligatoire est autorisé SOUS CERTAINES CONDITIONS : 1ère condition : la commune du lieu de brûlage est en vert dans la carte ci-contre 2ème condition : le lieu de brûlage est en forêt, bois, plantations, reboisements, landes, ainsi que tous les terrains situés à moins de 200 mètres de ces espaces cartes à consulter sur http://www.hautes-alpes.gouv.fr/atlas-cartographique-du- pdpfci-a1892.html Voir liste des communes ou parties de communes au verso Si NON à l’une de ces 2 conditions alors PAS DE DEROGATION, BRULAGE DES DECHETS VERTS INTERDIT Si DEROGATION possible selon les périodes d’emploi du feu : OUI en toutes périodes l'usage du feu est interdit par vent supérieur à 40 km/h, verte (15/09 au 14/03) : emploi du feu libre orange (15/03 au 14/09) : emploi du feu soumis à déclaration préalable en mairie rouge : INTERDIT rafales comprises Si OUI OBLIGATION de respecter les consignes suivantes POUR LES PÉRIODES VERTE ET ORANGE : - Informer les pompiers (18 ou 112) le matin même de l'emploi du feu, en précisant la localisation du feu, - profiter d'un temps calme, - effectuer le brûlage entre 10 et 15 heures, de préférence le matin, Alternative au brûlage : - ne pas laisser le feu sans surveillance, Afin de préserver la qualité de l’air, l’élimination des déchets verts - disposer de moyens permettant une extinction rapide, en décheterie ou par broyage est à privilégier - éteindre totalement le feu avant le départ du chantier et au plus tard à 15 heures. -

LES RISQUES MAJEURS DANS LA DROME Dossier Départemental Des Risques Majeurs

LES RISQUES MAJEURS DANS LA DROME Dossier Départemental des Risques Majeurs PRÉFECTURE DE LA DRÔME DOSSIER DÉPARTEMENTAL DES RISQUES MAJEURS 2004 Éditorial Depuis de nombreuses années, en France, des disposi- Les objectifs de ce document d’information à l’échelle tifs de prévention, d'intervention et de secours ont été départementale sont triples : dresser l’inventaire des mis en place dans les zones à risques par les pouvoirs risques majeurs dans la Drôme, présenter les mesures publics. Pourtant, quelle que soit l'ampleur des efforts mises en œuvre par les pouvoirs publics pour en engagés, l'expérience nous a appris que le risque zéro réduire les effets, et donner des conseils avisés à la n'existe pas. population, en particulier, aux personnes directement Il est indispensable que les dispositifs préparés par les exposées. autorités soient complétés en favorisant le développe- Ce recueil départemental des risques majeurs est le ment d’une « culture du risque » chez les citoyens. document de référence qui sert à réaliser, dans son pro- Cette culture suppose information et connaissance du longement et selon l’urgence fixée, le Dossier risque encouru, qu’il soit technologique ou naturel, et Communal Synthétique (DCS) nécessaire à l’informa- 1 doit permettre de réduire la vulnérabilité collective et tion de la population de chaque commune concernée individuelle. par au moins un risque majeur. Cette information est devenue un droit légitime, défini Sur la base de ces deux dossiers, les maires ont la par l’article 21 de la loi n° 87-565 du 22 juillet 1987 responsabilité d’élaborer des documents d’information relative à l'organisation de la sécurité civile, à la protec- communaux sur les risques majeurs (DICRIM), qui ont tion de la forêt contre l'incendie et à la prévention des pour objet de présenter les mesures communales d’a- lerte et de secours prises en fonction de l’analyse du risques majeurs. -

Recueil Des Actes Administratifs N°05-2017-187

RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS N°05-2017-187 HAUTES-ALPES PUBLIÉ LE 1 DÉCEMBRE 2017 1 Sommaire Agence régionale de santé PACA – DT des Hautes-Alpes 05-2017-10-17-008 - Décision modificative portant désignation du directeur par intérim de l'EHPAD Résidence François PAVIE à Savines-le-Lac (Hautes-Alpes) (2 pages) Page 5 05-2017-11-23-004 - Décision portant modification concernant l'agrément de transports sanitaires terrestres de la société " AMBULANCES VOLPE" (agrément numéro 50-05) (2 pages) Page 8 05-2017-11-16-003 - DECISION TARIFAIRE N°1671 PORTANT MODIFICATION DU FORFAIT GLOBAL DE SOINS de l'EHPAD CHABRE - LARAGNE MONTEGLIN (3 pages) Page 11 05-2017-11-13-010 - DÉCISION TARIFAIRE N°1675 PORTANT MODIFICATION DU FORFAIT GLOBAL DE SOINS POUR L'EHPAD LES CHANTERELLES (3 pages) Page 15 05-2017-11-13-011 - DÉCISION TARIFAIRE N°1872 PORTANT MODIFICATION DU FORFAIT GLOBAL DE SOINS POUR L'EHPAD ÉTOILE DES NEIGES (3 pages) Page 19 05-2017-11-13-009 - DÉCISION TARIFAIRE N°1879 PORTANT MODIFICATION DU FORFAIT GLOBAL DE SOINS POUR L'EHPAD LES SABOTS DE VENUS (3 pages) Page 23 05-2017-11-13-012 - DÉCISION TARIFAIRE N°1880 PORTANT MODIFICATION DU FORFAIT GLOBAL DE SOINS POUR L'EHPAD LOU VILAGE (3 pages) Page 27 05-2017-11-16-004 - DECISION TARIFAIRE N°1888 PORTANT MODIFICATION DU FORFAIT GLOBAL DE SOINSPOUR L’ANNEE 2017 DE L'EHPAD LE BUECH - LARAGNE MONTEGLIN (3 pages) Page 31 05-2017-11-16-002 - DECISION TARIFAIRE N°1919 PORTANT MODIFICATION DU PRIX DEJOURNEE POUR L’ANNEE 2017 DEMAS SOLEIL AME - LARAGNE MONTELIN (3 pages) Page 35 05-2017-11-16-007 - DÉCISION TARIFAIRE N°1938 PORTANT MODIFICATION DU FORFAIT GLOBAL DE SOINS POUR LE FAM L'HARMONIE (2 pages) Page 39 05-2017-11-16-008 - DÉCISION TARIFAIRE N°1939 PORTANT MODIFICATION DU FORFAIT GLOBAL DE SOINS POUR LE FAM L'OUSTALOU (2 pages) Page 42 Direction départementale de la cohésion sociale et de la protection des populations des Hautes-Alpes 05-2017-11-08-005 - Arrêté préfectoral modifiant l'arrêté 2012130.0001 du 9 mai 2012Mme le Dr. -

Téléchargez Le Dépliant Détaillé De Toutes Les Locations Partenaires De

Meublés de Tourisme & hébergements insolites en Ventoux Provence GUIDE 2021 www.ventouxprovence.fr Capacité Canapé convertible Sauna Handicap moteur Nombre de couverts Climatisation Télévision Handicap visuel Nombre de chambres Club enfants Terrain de tennis Clientèle Espace aquatique ludique Terrain clos Nombre de chambres accessibles Famille + Garage Terrasse Nombre de dortoirs Spécial famille avec enfants Jacuzzi® Nombre d’emplacements Labels Groupes Lave linge privatif Nombre d’emplacements de camping-car Qualité Tourisme™ Lave vaisselle Moyens de paiement Nombre de personnes Logis Matériel Bébé Carte bancaire/crédit Nombre de lit double Gîtes de France Non fumeur Chèque Vacances Nombre de lit simple Clévacances Parking Titre Restaurant Commodités Camping Qualité Parking autocar Chèque Wifi Internet Bienvenue à la ferme Piscine Aire de stationnement camping-cars Piscine chauffée Accessibilité Aire de jeux Piscine couverte Accessible en fauteuil roulant Animaux acceptés Restaurant Handicap auditif Ascenseur Salle de réunion Handicap mental Bar NOS MEUBLÉS DE TOURISME PARTENAIRES - 2021 MEUBLÉS ET GÎTES LE CLOS DES OLIVIERS - MARGUERITE HHH ©A.FERRE "Marguerite", gîte de charme avec piscine au Clos des Oliviers à 2 ch. 4/4 1 2 Aubignan. En famille ou entre amis, un cadre accueillant et reposant pour vos vacances au cœur de la Provence. Toute l'année. SEMAINE WEEK END 372 Chemin de Gargamiane - 84810 Aubignan Tél. 06 17 25 75 51 [email protected] 450 > 1050 € 120 > 300 € www.leclosdesoliviers.net MEUBLÉS ET GÎTES LE CLOS DES OLIVIERS - YVONNE HHH ©A.FERRÉ "Yvonne", gîte de charme avec piscine au Clos des Oliviers à 2 ch. 4/4 1 2 Aubignan. En famille ou entre amis, un cadre accueillant et reposant pour vos vacances au cœur de la Provence. -

Nouveau Territoire D'itinérance

Alpes de Haute-Provence / Provincia di Cuneo nuovo territorio da scoprire - nouveau territoire d’itinérance Produits labellisés Huile d’olive Autoroutes Patrimoine naturel remarquable Olio d’oliva Routes touristiques / Strade turistiche Autostrade Patrimonio naturale notevole Torino Torino Fromage de Banon Carignano Routes principales Espaces protégés Formaggio di Banon Route des Grandes Alpes Asti Strada principale Strada delle Grandi Alpi Aree protette Vins régionaux / Caves / Musées Variante Routes secondaires Sommets de plus de 3 000 mètres Asti Enoteche regionali / Cantine / Musei Pinerolo Strada secondaria Routes de la lavande Montagne >3.000 metri Agneau de Sisteron Strade della lavanda Rocche del Roero Voies ferrées Via Alpina Agnello di Sisteron Ferrovie Itinéraire rouge - Point d’étape Casalgrasso Montà Govone Itinerario rosso – Punto tappa Canale Vergers de la Durance Route Napoléon Ceresole Polonghera S. Stefano Roero Priocca Train des Pignes Strada Napoléon Itinéraire bleu - Point d’étape Faule Caramagna d’Alba Frutteti della Durance Piemonte Monteu Roero Les Chemins de fer Itinerario blu – Punto tappa Castellinaldo de Provence Montaldo Vezza Sommariva Roero d’Alba Magliano Point étape des sentiers de randonnée trekking Racconigi d. Bosco Alfieri Maisons de produits de pays Murello Baldissero Digne-les-Bains > Cuneo Bagnolo Moretta d’Alba Castagnito Points de vente collectifs Piemonte Sanfrè Corneliano Punto tappa dei sentieri di trekking Cavallerieone Sommariva d’Alba Aziende di prodotti locali Perno Digne-les-Bains > Cuneo Rucaski Cardè Guarene Neive Raggruppamento di produttori con vendita diretta Villanova Piobesi M. Granero Torre Monticello Solaro d’Alba 3.171 m Abbazia S. Giorgio Pocapaglia d’Alba Barbaresco Barge Staffarda Castiglione Marchés paysans C. d.