Agency for International Development Ppc/Cdie/Di

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport Sur Les Indicateurs De L'eau Et De L'assainissement

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER ----------------------------------------- FRATERNITE – TRAVAIL - PROGRES ------------------------------------------- MINISTERE DE L’HYDRAULIQUE ET DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT ---------------------------------------- COMITE TECHNIQUE PERMANENT DE VALIDATION DES INDICATEURS DE L’EAU ET DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT RAPPORT SUR LES INDICATEURS DE L’EAU ET L'ASSAINISSEMENT POUR L’ANNEE 2016 Mai 2017 Table des matières LISTE DES SIGLES ET ACRONYMES I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 II. DEFINITIONS ..................................................................................................................... 1 2.1. Définitions de quelques concepts et notions dans le domaine de l’hydraulique Rurale et Urbaine. ................................................................................................................ 1 2.2. Rappel des innovations adoptées en 2011 ................................................................... 2 2.3. Définitions des indicateurs de performance calculés dans le domaine de l’approvisionnement en eau potable ................................................................................... 3 2.4. Définitions des indicateurs de performance calculés dans le domaine de l’assainissement .................................................................................................................... 4 III. LES INDICATEURS DES SOUS – PROGRAMMES DU PROSEHA .......................... 4 IV. CONTRAINTES ET PROBLEMES -

Republique Du Niger

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Ministère de l’Hydraulique et de l’Assainissement Direction Générale des Ressources en eau Direction de l’Hydrogéologie ETAT DE MISE EN ŒUVRE DES ACTIVITES DU PROJET DANS LE COMPLEXE AQUIFERE DU LIPTAKO GOURMA AU NIGER RAF7011 – Gestion intégrée et durable des ressources en eau en Afrique axé sur les États Membres de la région du Sahel Vienne, du 05 au 08 Mai 2014 Présenté par Sanoussi RABE, Ingénieur Hydrogéologue DHGL/DGRE/MH/A PLAN DE L’EXPOSE 1. Présentation du complexe Aquifère du Liptako Gourma 2. Les principaux problèmes hydrogéologiques identifiés dans le bassin ; 3. Critères utilisés pour la sélection des points de prélèvement ; 4. Liste des personnes directement impliquées dans les activités ; 5. Principaux problèmes rencontrés lors des missions de terrain ; 6. Etat de lieux sur les données de base (Base des données et cartes thématiques de la zone du projet) 7. Conclusion et perspectives Introduction Introduction Capitale Niamey Superficie (km2) 1 267 000 Superficie de la zone d’intervention par pays (km2) 123 805 Densité (hbt/km2) 10 Population Ensemble 13 044 973 Zone ALG 4 839 638 Taux de croissance démographique 3,3 Ensemble 7+CUN Découpage administratif Zone ALG 2+CUN Introduction Le Liptako Gourma est une région enclavée aux conditions très difficiles du fait de la rareté des ressources en eaux dont les plus importantes sont situées dans des aquifères discontinus et dont les débits sont très faibles. Cette région qui regroupe le Burkina Faso, le Mali et le Niger.est concernée par le aquifères des grands bassins hydrogéologiques. Introduction 0 1 2 3 4 5 MALI 15 REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER 15 TA HO UA Projet RAF7011/AIEA %[ Ayorou CARTE DE LA REGION DU LIPTAKO GOURMA ILLELA OU ALLA M FILING UE ]' ]' Tillaberi ]%[' TERA 14 ]' 14 BIRN I N 'K ON N I N DOG ON DO UTC HI ]' NIAMEY ]' LO GA O E %[ S KOLLO ]' %[ Dosso BURKINA FASO ]' ]' SAY ]' 13 BIRN IN GA OU RE 13 30 0 30 60 Kilomètres 12 Gaya 12 %[]' 0 1 2 3 4 5 2. -

F:\Niger En Chiffres 2014 Draft

Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 1 Novembre 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Direction Générale de l’Institut National de la Statistique 182, Rue de la Sirba, BP 13416, Niamey – Niger, Tél. : +227 20 72 35 60 Fax : +227 20 72 21 74, NIF : 9617/R, http://www.ins.ne, e-mail : [email protected] 2 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Pays : Niger Capitale : Niamey Date de proclamation - de la République 18 décembre 1958 - de l’Indépendance 3 août 1960 Population* (en 2013) : 17.807.117 d’habitants Superficie : 1 267 000 km² Monnaie : Francs CFA (1 euro = 655,957 FCFA) Religion : 99% Musulmans, 1% Autres * Estimations à partir des données définitives du RGP/H 2012 3 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 4 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Ce document est l’une des publications annuelles de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Il a été préparé par : - Sani ALI, Chef de Service de la Coordination Statistique. Ont également participé à l’élaboration de cette publication, les structures et personnes suivantes de l’INS : les structures : - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Economiques (DSEE) ; - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Démographiques et Sociales (DSEDS). les personnes : - Idrissa ALICHINA KOURGUENI, Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Ibrahim SOUMAILA, Secrétaire Général P.I de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Ce document a été examiné et validé par les membres du Comité de Lecture de l’INS. Il s’agit de : - Adamou BOUZOU, Président du comité de lecture de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Djibo SAIDOU, membre du comité - Mahamadou CHEKARAOU, membre du comité - Tassiou ALMADJIR, membre du comité - Halissa HASSAN DAN AZOUMI, membre du comité - Issiak Balarabé MAHAMAN, membre du comité - Ibrahim ISSOUFOU ALI KIAFFI, membre du comité - Abdou MAINA, membre du comité. -

Etat Des Lieux De La Riziculture Au Niger

Etat des lieux de la riziculture au Niger Elaboré par Sido Amir Novembre 2011 Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’Alimentation et l’Agriculture Etat des lieux de la riziculture au Niger Amir Sido / Assistant technique APRAO-Niger Niamey, Niger Abdoulkarim Alkaly, consultant, Niamey, Niger Abdou Maliki, consultant, Niamey, Niger Projet Amélioration de la production de riz en Afrique de l’Ouest en réponse à la flambée de prix des denrées alimentaires République du Niger Organisation des Nations unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture Agence espagnole de coopération internationale pour le développement ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L’ALIMENTATION ET L’AGRICULTURE Rome, 2011 Etat des lieux de la riziculture au Niger TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES TABLEAUX ..................................................................................................................................... 3 AVANT-PROPOS ................................................................................................................................................. 6 REMERCIEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 8 1. CONTEXTE GENERAL ................................................................................................................................. 9 2. IMPORTANCE ECONOMIQUE -

ٍٍRapport Monitoring Protection Tillaberi Avril2018.Pdf

RAPPORT D’ANALYSE MENSUELLE DES DONNEES DU MONITORING DE PROTECTION avril 2018 Tillabéri, Niger Entretien avec des nouveaux arrivés à Inatès (ANTD, avril 2018) 1 I. APERCU DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT SECURITAIRE ET DE PROTECTION DANS LA REGION DE TILLABERI La situation sécuritaire dans la ré- des exactions de part et d’autres # TOTAL DES PDIs DANS LA RE- gion de Tillaberi au cours du mois des deux communautés (per- GION DE TILLABERI d’Avril est restée très instable par- sonnes tuées, banditisme armé, ticulièrement dans les localités vol de bétail, villages menacés). frontalières avec le Mali et le Bur- Selon certaines sources, les con- kina-Faso, en raison de la conduite flits intercommunautaires entre 11,033 des opérations militaires menées peulhs et touaregs pourraient aug- par les Groupes armés signataires menter le nombre de recrutement de la plateforme (GATIA/MSA-D), de jeunes en particulier d’ethnies soutenue par les forces françaises peulhs pour rejoindre les groupes de Barkhane, des violents affron- armés et défendre leur familles EVOLUTION DU NOMBRE DES tements armés entre les commu- menacées. PDIs DE JANVIER A AVRIL 2018 nautés Fulani et Daoussak au Mali, Au cours du mois d’avril, il a été sig- 11033 ainsi que des actions des éléments nalé une migration des éléments des groupes armés non étatiques des groupes armés non étatiques 7477 8017 de part et d’autres des différents vers les localités frontalières avec pays. le Burkina-Faso (Bankilaré, Toro- L’assassinat au Mali au cours du di) et à l’est d’Abala ainsi que vers mois d’avril 2018 d’un chef mil- des zones moins couvertes par les itaire du GATIA et d’un officier opérations militaires. -

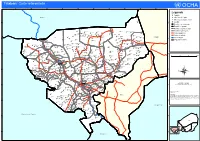

NIGER: VILLAGES SUIVIS DANS LES 5 DEPARTEMENTS SOUS ETAT D'urgence DANS LA REGION DE TILLABERI Au 5 Mai 2018 1°0'0"E 2°0'0"E 3°0'0"E 4°0'0"E

NIGER: VILLAGES SUIVIS DANS LES 5 DEPARTEMENTS SOUS ETAT D'URGENCE DANS LA REGION DE TILLABERI Au 5 mai 2018 1°0'0"E 2°0'0"E 3°0'0"E 4°0'0"E Légende ! Chef lieu du département 50km # Village à haut risque de déplacement D Village ayant connu un déplacement M A L II " Village accueillant des déplacés internes ^ Village à suivre par le monitoring de protection 10 # Limite départementale 76 #6 9# 49 # 5 8 53 48#" #42 D 75 # #" "" 65 D# 68 # #55 # 57 D#74 # 4 # 3 Limite communale #" # # 1 # #7 11 12 " 52 # # 73 64 D# 67 D# 15 # # 19 37# 72 ## # 66 69 70 # # #" 61 60 59 63 # # # Département sous état d'urgence 51 #" # # 62 D # # 20 35 50 58 #13 16 17 # 18 #" #"54 INATES 71 # 34 D # " 77 Banibangou # # N # " 41 N " Limite internationale #43 # BANIBANGOU ! " 0 44 45 14 0 ' 56 " #" #" # ' 0 40 D# 0 ° " 47 BANIBANGOU SANAM ° 5 24 21 38 39 5 1 # #33 D# Abala 1 # 30 46 D#" #" D# #" ABALA ! # ## 26 36 ABALA # 29 25#" 31 22 #27 93 32 ^ # 94^95 23 #28 GOROUAL ^ ^96 98 Ayorou TONDIKIWINDI 84 103 ^ ^^ ! ^^ 97 AYOROUAYOROU 83 99 92 100 ^ ^ Ayorou ANZOUROU ^102 Bankilare DINGAZIBANDA KOURFEYE-FILINGUE ! ^91 DESSA 86 BANKILARE 82 ^ BANKILARE OUALLAM ^ 85 BIBIYERGOU 1 Miel 26 Agamsourgou 51 Tagdounatt 76 Inzouett 101 Petelkole ^ MEHANA 88 2 Miel Cimint 27 Tinfagatt 52 Inassarara 77 Tilloa 102 Dolbel 79 SAKOIRA Filingue ^ ^ Ouallam 3 Tigueze Fan Raoufi 28 Tinagangan 53!Imbouga 78 Bouppo 103 Gorouol 80 TILLABERI ! 4 Tiguezefan Issa 29 Yassane Nomade 54 Tamagaste 79 Lemdou ^ ^81 SINDER OUALLAM 5 Tiguezefantabre 30 Alewayane 55 Inates 80 Tinawass 90 KOKOROU -

Ref Tillaberi A1.Pdf

Tillabéri: Carte référentielle 0°0'0" 0°30'0"E 1°0'0"E 1°30'0"E 2°0'0"E 2°30'0"E 3°0'0"E 3°30'0"E 4°0'0"E 4°30'0"E Légende !^! Capitale M a l i !! Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département N N " Digue Diga " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 Localité ° ° 5 5 1 1 Frontière internationale Frontière régionale Zongodey Frontière départementale Chinégodar Dinarha Tigézéfen Gouno Koara Chim Berkaouan Frontière communale In Tousa Tamalaoulaout Bourobouré Mihan Songalikabé Gorotyé Meriza Fandou Kiré Bissao Darey Bangou Tawey Térétéré Route goudronée Momogay Akaraouane Abala Ngaba Tahououilane Adabda Fadama Tiloa Abarey Tongo Tongo BANIBANGOU Bondaba Jakasa Route en latérite Bani Bangou Fondé Ganda Dinara Adouooui Firo ! Ouyé Asamihan N N " Tahoua " 0 Abonkor 0 ' Inates ' 0 Siwili Tuizégorou Danyan Kourfa 0 ° ° Fleuve Niger 5 Alou Agay 5 1 1 Sékiraoey Koutougou Ti-n-Gara Gollo Soumat Fadama ABALA Fartal Sanam Yassan Katamfransi ! Banikan Oualak Zérma Daré Doua I-n-Tikilatène Gawal Région de Tillabéri Yabo Goubara Gata Garbey Tamatchi Dadi Soumassou Sanam Tiam Bangou Kabé Kaina Sama Samé Ouèlla Sabon Gari Yatakala Mangaizé-Keina Moudouk Akwara Bada Ayerou Tonkosom Amagay Kassi Gourou Bossé Bangou Oussa Kaourakéri Damarké Bouriadjé Ouanzerbé Bara Tondikwindi Mogodyougou Gorou Alkonghi Gaya AYOROU Boni Gosso Gorouol ! Foïma Makani Boga Fanfara Bonkwari Tongorso Golbégui Tondikoiré Adjigidi Kouka Goubé Boukari Koyré Toumkous Mindoli Eskimit Douna Mangaïzé Sabaré Kouroufa Aliam Dongha Taroum Fégana Kabé Jigouna Téguey Gober Gorou Dambangiro Toudouni Kandadji Sassono -

July, 1984 USAID, Niamey NIGER IRRIGATION SUBSECTOR

NIGER IRRIGATION SUBSECTOR ASSESSMENT VOLUME ONE MAIN REPORT July, 1984 Glenn Anders, Irrigation Engineer USAID, Niamey Walter Firestone, Agronomist Michael Gould, Environmental Specialist Emile Malek, Public Health Specialist Emmy Simmons, arming Systems Economist Malcolm Versel, Vegetable Marketing Teresa Ware, Institutional Analyst Tom Zalla, Team Leader NIGER IRRIGATION SUB-SECTOR A.SSESSMENT Table of Contents Paae EXECUTIV.E S==",R L.. .......... i i. INTRODU2 0N...... ................. II. GOVERNMENT AND DONOR ACTIVITIES RELATED TO IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE ...... ........... 2 A. Government of Niger Institutions ....... 2 1, Ministrv of Rqal Development (MDR) . 2 2. Ministry of Hydrology and the Environment (AHE) ........... 3 3. Ministry of Higher Education and Research (MESR) ...... ............ 4 B. Donor Activities ....... ............. 4 III. IRRIGATION SYSTEMS IN NIGER .... ........ 5 A. Jointly Managed River Pumping Systems . 6 B. Jointly Managed Surface Dam Systems . 6 C. Jointly Managed Ground Water Pumping Systems ........................ 7 D. Individual Managed Micro-Irrigation Systems ......... ................. 7 IV. ENGINEERING ASPECTS OF IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE IN NIGER .......... .................. 8 A. Factors Influencing Development Costs . 9 1. Topography ........ ............... 9 2. Design Standards... ............ 11 3. Competition ..... .............. 12 4. Risk and Uncertainty... .......... .. 12 B. Water Supply and Management Problems. 13 C. System Maintenance. ............... 14 D. Feasibility of Promoting -

Stratégie De Développement Rural

République du Niger Comité Interministériel de Pilotage de la Stratégie de Développement Rural Secrétariat Exécutif de la SDR Stratégie de Développement Rural ETUDE POUR LA MISE EN PLACE D’UN DISPOSITIF INTEGRE D’APPUI CONSEIL POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL AU NIGER VOLET DIAGNOSTIC DU RÔLE DES ORGANISATIONS PAYSANNES (OP) DANS LE DISPOSITIF ACTUEL D’APPUI CONSEIL Rapport provisoire Juillet 2008 Bureau Nigérien d’Etudes et de Conseil (BUNEC - S.A.R.L.) SOCIÉTÉ À RESPONSABILITÉ LIMITÉE AU CAPITAL DE 10.600.000 FCFA 970, Boulevard Mali Béro-km-2 - BP 13.249 Niamey – NIGER Tél : +227733821 Email : [email protected] Site Internet : www.bunec.com 1 AVERTISSEMENTS A moins que le contexte ne requière une interprétation différente, les termes ci-dessous utilisés dans le rapport ont les significations suivantes : Organisation Rurale (OR) : Toutes les structures organisées en milieu rural si elles sont constituées essentiellement des populations rurales Organisation Paysanne ou Organisation des Producteurs (OP) : Toutes les organisations rurales à caractère associatif jouissant de la personnalité morale (coopératives, groupements, associations ainsi que leurs structures de représentation). Organisation ou structure faîtière: Tout regroupement des OP notamment les Union Fédération, Confédération, associations, réseaux et cadre de concertation. Union : Regroupement d’au moins 2 OP de base, c’est le 1er niveau de structuration des OP. Fédération : C’est un 2ème niveau de structuration des OP qui regroupe très souvent les Unions. Confédération : Regroupement les fédérations des Unions, c’est le 3ème niveau de structuration des OP Membre des OP : Personnes physiques ou morales adhérents à une OP Adhérents : Personnes physiques membres des OP Promoteurs ou structures d’appui ou partenaires : ce sont les services de l’Etat, ONG, Projet ou autres institutions qui apportent des appuis conseil, technique ou financier aux OP. -

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique Au Niger»

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique au Niger» DIFEB, le 16 Août 2019 SOMMAIRE CEV Plan de déploiement Détails Zone 1 Détails Zone 2 Avantages/Limites CEV Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote CEV: Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote Notion apparue avec l’introduction de la Biométrie dans le système électoral nigérien. ▪ Avec l’utilisation de matériels sensible (fragile et lourd), difficile de faire de maison en maison pour un recensement, C’est l’emplacement physique où se rendront les populations pour leur inscription sur la Liste Electorale Biométrique (LEB) dans une localité donnée. Pour ne pas désorienter les gens, le CEV servira aussi de lieu de vote pour les élections à venir. Ainsi, le CEV contiendra un ou plusieurs bureaux de vote selon le nombre de personnes enrôlées dans le centre et conformément aux dispositions de création de bureaux de vote (Art 79 code électoral) COLLECTE DES INFORMATIONS SUR LES CEV Création d’une fiche d’identification de CEV; Formation des acteurs locaux (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil) pour le remplissage de la fiche; Remplissage des fiches dans les communes (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil et 3 personnes ressources); Centralisation et traitement des fiches par commune; Validation des CEV avec les acteurs locaux (Traitement des erreurs sur place) Liste définitive par commune NOMBRE DE CEV PAR REGION Région Nombre de CEV AGADEZ 765 TAHOUA 3372 DOSSO 2398 TILLABERY 3742 18 400 DIFFA 912 MARADI 3241 ZINDER 3788 NIAMEY 182 ETRANGER 247 TOTAL 18 647 Plan de Déploiement Plan de Déploiement couvrir tous les 18 647 CEV : Sur une superficie de 1 267 000 km2 Avec une population électorale attendue de 9 751 462 Et 3 500 kits (3000 kits fixes et 500 tablettes) ❖ KIT = Valise d’enrôlement constitués de plusieurs composants (PC ou Tablette, lecteur d’empreintes digitales, appareil photo, capteur de signature, scanner, etc…) Le pays est divisé en 2 zones d’intervention (4 régions chacune) et chaque région en 5 aires. -

Niger AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Fraternity – Work - Progress ------Prime Minister’S Office ------AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND High Commission for Niger Valley Development

Republic of Niger AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Fraternity – Work - Progress ------------ ------------------------ Prime Minister’s Office ------------ AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND High Commission for Niger Valley Development "KANDADJI" ECOSYSTEMS REGENERATION AND NIGER VALLEY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (KERNVDP) DETAILED ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY January 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms.........................................................................................................................i 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 2. Description and Rationale of the KERNVDP .................................................................... 1 3. Policy, Legal and Institutional Framework ........................................................................ 3 3.1. Policy Framework ...................................................................................................... 3 3.1.1. Relevant ADB Crosscutting Policies ..................................................................... 3 3.1.2. International Conventions, Protocols, Treaties and Agreements. .......................... 4 3.1.3. Legal Environmental Framework........................................................................... 5 3.1.4. Legal Social Framework ........................................................................................ 5 3.2. Institutional and Administrative Framework ............................................................ -

Rapport Monitoring Protection Tillaberi Juin 2018

RAPPORT D’ANALYSE MENSUELLE DES DONNEES DU MONITORING DE PROTECTION juin 2018 Tillabéri, Niger 1 # TOTAL DES PDIs DANS LA RE- I. APERCU DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT SECURITAIRE ET GION DE TILLABERI DE PROTECTION DANS LA REGION DE TILLABERI Le contexte sécuritaire reste volatile dans la bande frontalière avec le Mali. Le mois de juin a été marqué par la poursuite des opérations mil- 17,758 itaires, conséquence du climat d’insécurité et de l’instabilité à la fron- tière entre le Niger (régions de Tillabéri et Tahoua) et le Mali (région de Menaka). Dès lors, l’opération Koufra 5 impliquant les forces Dongo, Barkane, et d’autres forces se poursuit à la frontière Tillaberi/Menaka, ainsi que d’autres opérations militaires de ratissage dans les communes # TOTAL DES PDIs PAR DEPARTE- de Baninbangou, Ouallam, Inates, Aballa. MENT De source sécuritaire, une grande partie des groupes armés chassés 13,238 ou dispersés par lesdites interventions militaires, se seraient déplacés vers d’autres localités des communes d’Anzourou, Baninbangou, Abala, Tondikiwindi, Bankilaré dans la région de Tillaberi. Des caches d’armes et des motos ayant été retrouvées par les militaires témoignent de l’in- filtration des membres de ces groupes dans les communautés locales. Dans le sillage des conflits armés et des conflits intercommunautaires 2,655 au Mali, la prolifération des armes à feu est une grande menace puis- 1,200 que cela augmente le niveau de violence au sein des communautés. 665 Cela a notamment favorisé l’accroissement des cas de brigandage à l’arme, d’intimidation et de menace de la population par les groupes Banibangou Ouallam Abala Ayorou qui procèdent à des tirs en l’air.