The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holiday That Traditional Tljie Holiday. Has Un¬ Sabbath at 10:45 A.M

SCHEDULE OF YOM KIPPUR SERVICES Sunday, September 28th, Yom Kippur Eve Mincha 1:30 KOL NIDRE 5:30 Rabbi Lookstein will speak Monday, September 29th, Yom Kippur Morning .' 8:00 Memorial Service (Yizkor) 11:15 PLEASE NOTE that the hours indicated above are Eastern Standard Time which will go into effect this Sunday morning. PLANS MADE FOR FESTIVE SUKKOTH HOLIDAY The forthcoming Sukkoth festival As announced in last week's Bul¬ w ill long be remembered by those letin, arrangements have been com¬ w ho will participate in its celebration pleted for catered meals to be served at Kehilath Jeshurun. Plans are being in the Sukkah on the first two days mjade for the Sukkoth holiday that of the festival: Friday and Saturday wjill make for a beautiful as well as evenings and Saturday and Sunday eiiijoyable observance of the Feast of afternoons. The price per plate is Tfabernacles, without for one moment $6.00 — a nominal sum that will leasing sight of the ancient traditional cover everything that is required, in¬ practices that constitute the heart of cluding gratuities. In order to allow tljie holiday. enough time for the necessary ar¬ rangements, the dead-line for reserva¬ j Once again, the Sisterhood has un¬ tions has been set for Tuesday, Sep¬ dertaken to decorate the Sukkah. A tember 30th. We should like to re¬ gjvoup of the organization's members, mind you that all reservations must uirider the chairmanship of Mrs. be accompanied by check. David Joseph, are now planning to The true celebration of the holiday prepare the spacious Sukkah, which takes place proper. -

2018–2019 Annual Report

18|19 Annual Report Contents 2 62 From the Chairman of the Board Ensemble Connect 4 66 From the Executive and Artistic Director Digital Initiatives 6 68 Board of Trustees Donors 8 96 2018–2019 Concert Season Treasurer’s Review 36 97 Carnegie Hall Citywide Consolidated Balance Sheet 38 98 Map of Carnegie Hall Programs Administrative Staff Photos: Harding by Fadi Kheir, (front cover) 40 101 Weill Music Institute Music Ambassadors Live from Here 56 Front cover photo: Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, by Stephanie Berger. Stephanie by Chris “Critter” Eldridge, and Chris Thile National Youth Ensembles in Live from Here March 9 Daniel Harding and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra February 14 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, In the 12 months since the last publication of this annual report, we have mourned the passing, but equally importantly, celebrated the lives of six beloved trustees who served Carnegie Hall over the years with the utmost grace, dedication, and It is my great pleasure to share with you Carnegie Hall’s 2018–2019 Annual Report. distinction. Last spring, we lost Charles M. Rosenthal, Senior Managing Director at First Manhattan and a longtime advocate of These pages detail the historic work that has been made possible by your support, Carnegie Hall. Charles was elected to the board in 2012, sharing his considerable financial expertise and bringing a deep love and further emphasize the extraordinary progress made by this institution to of music and an unstinting commitment to helping the aspiring young musicians of Ensemble Connect realize their potential. extend the reach of our artistic, education, and social impact programs far beyond In August 2019, Kenneth J. -

Um Compositor Brasileiro Na Broadway: a Contribuição De Heitor Villa-Lobos Ao Teatro Musical Americano

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS ESCOLA DE MÚSICA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM MÚSICA - MESTRADO UM COMPOSITOR BRASILEIRO NA BROADWAY: A CONTRIBUIÇÃO DE HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS AO TEATRO MUSICAL AMERICANO ROSANE VIANA BELO HORIZONTE 2007 ROSANE VIANA UM COMPOSITOR BRASILEIRO NA BROADWAY: A CONTRIBUIÇÃO DE HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS AO TEATRO MUSICAL AMERICANO Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Mestrado da Escola de Música da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Música. Área de Concentração: Estudo das Práticas Musicais Sub-área: Análise Musical Orientador: Lucas Bretas Belo Horizonte Escola de Música da UFMG 2007 Dedico o presente trabalho ao meu pai, Sebastião Vianna. AGRADECIMENTOS Ao meu orientador, por ter aceitado o desafio de desbravar "terras incógnitas" sem medo de se arriscar e pela sua grande capacidade. A Mônica Mansur Brandão, pela ajuda inestimável e imprescindível no pré-projeto. A Maria Eugênia Albinatti, pelo seu "ouvido paciente" nesses dois anos e sua colaboração. A David Peterson, meu "dicionário vivo" em momentos cruciais. A Rita Lopes Moreira, pela sua generosidade, sem a qual eu não poderia sequer ter iniciado o Curso de Mestrado. Ao meu pai, pelas informações preciosas e inéditas sobre Magdalena e tantas outras sobre Villa-Lobos. Agradeço também pela sua ajuda financeira durante esse período. A minha saudosa mãezinha, Rosa Nalterelli Viana, pelo seu entusiasmo e incentivo quando descobri a obra em 2000. A Sandra Loureiro, pelas palavras sábias em momentos difíceis e por compartilhar comigo a alegria de escrever sobre Magdalena. A André Cavazotti, por ter carinhosamente me acolhido na sub-área Análise Musical e por ter sempre respondido aos meus e-mails e retornado meus telefonemas. -

Beethoven's 9Th Symphony

The Greater Utica Choral Society presents The Clinton Symphony Orchestra of the Mohawk Valley Charles Schneider, Music Director Saturday, December 19, 2015 Clinton Central Schools Performing Arts Complex 8:00 p.m. Beethoven’s 9th Symphony Featuring soloists Alexia Mate, Soprano; Carolyn Weber, Mezzo-soprano; Jon Fredric West, Tenor; Eric Johnson, Bass; and Choral Singers from Central New York Sponsors: Fiber Instrument Sales ♫ Strategic Financial Services CHARLES SCHNEIDER, Music Director An award-winning and versatile musician, Maestro Schneider's experience spans the musical spectrum - Broadway musical theatre, opera, pops and symphonic music. He conducted the 1967 CBS Television Special of the Year with Jimmy Durante, The Supremes and Jimmy Dean. He was the Music Director of the off- Broadway hit “Your Own Thing” that won the 1968 New York Critics Award (first time ever for an off- Broadway show). He was the Music Director for Juliet Prowse, Dorothy Sarnoff and Broadway legend John Raitt. A number of upstate New York perform- ance organizations have benefited from Charles Schnei- der's guidance and expertise: he has conducted the Catskill Symphony since 1973, was the Music Direc- tor of the Utica Symphony from 1980-2011, and of the Schenectady Symphony Orches- tra since 1982. In addition, Mr. Schneider has served as Music Director of the Portland (Oregon) Chamber Orchestra. He was the founding music director of Glimmerglass Opera, a position he held for 12 years. He was also co-founder of the Catskill Conser- vatory of Music (Oneonta, NY). Additionally, he conducted the United States premiere of Bertold Brecht and Kurt Weill’s “The Rise and Fall of the City Mahagonny” with the San Francisco Opera. -

Department of Defense Appropriations for 2014 Hearings

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE APPROPRIATIONS FOR 2014 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEFENSE C. W. BILL YOUNG, Florida, Chairman RODNEY P. FRELINGHUYSEN, New Jersey PETER J. VISCLOSKY, Indiana JACK KINGSTON, Georgia JAMES P. MORAN, Virginia KAY GRANGER, Texas BETTY MCCOLLUM, Minnesota ANDER CRENSHAW, Florida TIM RYAN, Ohio KEN CALVERT, California WILLIAM L. OWENS, New York JO BONNER, Alabama MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TOM COLE, Oklahoma STEVE WOMACK, Arkansas NOTE: Under Committee Rules, Mr. Rogers, as Chairman of the Full Committee, and Mrs. Lowey, as Ranking Minority Member of the Full Committee, are authorized to sit as Members of all Subcommittees. TOM MCLEMORE, JENNIFER MILLER, PAUL TERRY, WALTER HEARNE, MAUREEN HOLOHAN, ANN REESE, TIM PRINCE, BROOKE BOYER, BG WRIGHT, ADRIENNE RAMSAY, and MEGAN MILAM ROSENBUSCH, Staff Assistants SHERRY L. YOUNG, Administrative Aide PART 2 Page Defense Health Program ....................................................... 1 U.S. Africa Command .............................................................. 155 FY 2014 Navy and Marine Corps ......................................... 179 FY 2014 Army Budget Overview .......................................... 331 FY 2014 Air Force Budget Overview .................................. 421 Outside Witness Statements ................................................. 501 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 86–557 WASHINGTON : 2014 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS -

The Magazine of South Carolina

THE MAGAZINE OF SOUTH CAROLINA san One Dollar Twenty-Five JANUARY • 1971 THE GREATER GREENVILLE AREA APEX OF SOUTH CAROLINA INDUSTRY AND CULTURE ONE OF A SERIES DEPICTING UPPER SOUTH CAROLINA'S PROGRESS PROPOSED GREENVILLE DOWNTOWN COLISEUM AND CONVENTION CENTER "/"/Fr==i•E31 C:: - ,;C::,,,... "/I THE CENTER will have a seating capacity of approximately RADIO 133 13,000 for various stage shows, sporting events and GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA •MULTIMEDIA STATIONS conventions. Complementing the main area are separate exhibition and banquet facilities and a multistory ,~/Fr==iiE31 c::=: - ~ "/I parking building making this one of the most complete STEREO 937 and up to date complexes of its kind. ~7n today's world where talk comes cheap~ action speaks louder!' I When somebody wants to sell you something, you almost always know the words: We care. We understand. We're interested. We listen. We do more for you. We make it easy. It all sounds so meaningful. But by now you've realized that talk is cheap. And what's really important is the follow-through. At C&S Bank, we'll never waste words to tell you we care. Because saying it doesn't make it so. Action does. So come in. Try us. Find out about our services. Tell us what you think about the way we work for you. Write us if it's handier. We're dedicated to being the best bank in South Carolina. You say the words, we'll start the action. THE CITIZENS & SOUTHERN NATIONAL BANK OF SOUTH CAROLINA Member F.D.l.C. -

The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia

The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia Alfred W. McCoy with Cathleen B. Read and Leonard P.Adams II Contents Glossary Acknowledgements Introduction: The Consequences of Complicity Heroin: The History of a "Miracle Drug" The Logistics of Heroin 1. Sicily: Home of the Mafia Addiction in America: The Root of the Problem The Mafia in America The Mafia Restored Fighters for Democracy in World War II Luciano Organizes the Postwar Heroin Trade The Marseille Connection Mapa de la Conquista de Sicilia (1943) 2. Marseille: America's Heroin Laboratory Genesis From Underworld to Underground Political Bedfellows The Socialist Party, the Guerinis, and the CIA The Guerini-Francisci Vendetta After the Fall The Decline of the European Heroin Trade, and a Journey to the East 3. The Colonial Legacy: Opium for the Natives The Royal Thai Opium file:///I|/drugtext/local/library/books/McCoy/default.htm[24-8-2010 15:09:28] The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia Monopoly Burma Sahibs in the Shan states French Indochina The Friendly Neighborhood Opium Den The Opium Crisis of 1939- 1945 The Meo of Laos Politics of the Poppy Opium in the Tai Country Denouement at Dien Bien Phu Into the Postwar Era 4. Cold War Opium Boom French Indochina Opium Espionage and "Operation X" The Binh Xuyen Order and Opium in Saigon Secret War in Burma The KMT Thailand's Opium The Fruits of Victory Isn't it true that Communist China is the center of the Appendix international narcotics traffic? No 5. South Vietnam: Narcotics in the Nation's -

Tomeof a $15,000,000 Project

TV & RADIO LOGS-MAY S-14 Loretta Young's Own Story: The Mother Behind My Success Blue Ribbon Bouts: tomeof A $15,000,000 Project What's Wrong? TV Discovers 'Em; The Movies Grab 'em! fe INSPIRE THE PEN Mrs. Renzo Dare, Fontana experience that the ones who write about the Lord loving the common To the person who says she doesn't in are regulars who try to get on people because he made so many of like the Pallais Sisters on "Western every quiz show and do not make the them—is true. Attending the Liberace Varieties," all Ican say is she doesn't grade. In fact I never knew there concert in Pasadena it was interest- know good entertainment when she were so many jealous people until I ing to see how people really love him started going to the broadcasts. hears it and sees it, so let her turn —and he loves to play. He gives the KABC is one of the few studios that her dial. For me, the Pallais Sisters public what they want and is sin- are the best part of "Western tries to do anything about it, and they penalized some very nice people cerely grateful for his good fortune. Varieties." If it wasn't for them I He is so big hearted I imagine he wouldn't even tune in the show. on account of a few who thought they had special rights to be on every pro- would even hand out beans to starv- gram. ing critics. He won't be needing hand- Michael J. -

MASTER 3+3 14/5/09 9:52 AM Page 2

120885bk Street:MASTER 3+3 14/5/09 9:52 AM Page 2 Act I Act II. 1. Ain’t It Awful, The Heat 3:44 Scene 1 Also available in the Naxos Musicals series ... Maria Martino, Alice Lee, Catherine 11. Entr’acte: There’ll Be Trouble 9:00 Helgenberg & Ensemble Norman Atkins, Polyna Stoska & 2. I Got A Marble And A Star 1:29 Dorothy Sarnoff Ferdinand Hilt 12. A Boy Like You 2:47 3. Gossip Trio: Get A Load Of That 1:07 Polyna Stoska Maria Martino, Alice Lee, Catherine 13. We’ll Go Away Together 3:01 Helgenberg & Ensemble Brian Sullivan & Dorothy Sarnoff 4. When A Woman Has A Baby 1:42 14. The Woman Who Lived Up There 5:19 Chris Ortiz & Ensemble Ensemble 5. Scene: Somehow I Never Could Scene 2 Believe 8:19 15. Interlude—Lullaby 5:36 Polyna Stoska Nursemaids 8.120786 8.120845 8.120846 6. Ice Cream Sextet 4:38 16. I Loved Her Too 3:50 Henry Timmerman & Ensemble Norman Atkins, Dorothy Sarnoff & Ensemble 7. Let Things Be Like They Always Was 17. Don’t Forget The Lilac Bush; 3:00 Ain’t It Awful, The Heat 6:13 Norman Atkins Brian Sullivan & Dorothy Sarnoff, 8. Lonely House 3:50 Maria Martino, Alice Lee, Catherine Brian Sullivan Helgenberg & Ensemble 9. What Good Would The Moon Be? 5:26 Orchestra and Chorus under the direction Dorothy Sarnoff of Izler Solomon 10. Remember That I Care 5:33 Concert performance, Hollywood Bowl, Dorothy Sarnoff & Brian Sullivan 21 August 1949, recorded for overseas broadcast by Armed Forces Radio Service 8.120877 8.120878 8.120879 IE-38-99, Program 99, mx RL 15558/65 C The cast was specially assembled for this one concert and performers in some instances are These titles are not for retail sale in the USA uncertain but given here according to best knowledge. -

![Volume 44 Issue 31 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5295/volume-44-issue-31-pdf-3815295.webp)

Volume 44 Issue 31 [PDF]

MAY 1942 VOLUME NUMBER PRESIDENTDAY AND ARMYOFFICERS REVIEW THE ROTC IN BARTONHALL ALUMNI NEWS Advertisers: Your Message Gets Preferred Attention when addressed to the 67,000 Alumni Readers of COLUMBIA CORNELL DARTMOUTH HARVARD PENNSYLVANIA PRINCETON YALE For Group Advertising Rates, Details, and Schedules Write, Wire, or Phone Ivy League Alumni Magazines Charles E. Thorp 370 Lexington Ave. Representative New York City Please mention the CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS ELL ALU I NEWS Subscription price $4 a year. Entered as second class matter, Ithaca, N. Y. Published weekly during the college year and monthly during the summer VOL. XLIV, NO. 31 ITHACA, NEW YORK, MAY XI, 1942. PRICE, 15 CENTS HOTELMEN PROVE USEFUL IN WAR EFFORT By Professor Howard B. Meek, Head of Department of Hotel Administration Kevin E. Howard, who received the their studies in inactive status. Sixteen BS in Hotel Administration at Cornell This is the eleventh of our series on are cadet officers in the ROTC, thirteen in 1931, is now in charge of the equip- Cornell and World War II, outlining being assigned to the Quartermaster ment and operation of Pan-Anierican some of the contributions of various Corps. Another sixteen are in various Airways bases across equatorial Africa, Colleges and Departments of the Uni- branches of the Navy, eight in the used in ferrying US military planes to versity to the country's war effort. The Supply Corps. series began in our issue of February 26 the Near and Far East. Associated with Department Teaches Specialists him are ten other graduates of the and will continue in succeeding numbers. -

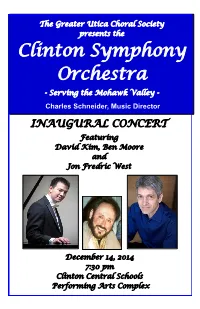

Dec 14 Program

The GreaterClinton Utica High SchoolChoral Society presentsDrama Club the Presents Clinton Symphony Orchestra - Serving the Mohawk Valley - Charles Schneider, Music Director INAUGURAL CONCERT Featuring David Kim, Ben Moore and Jon Fredric West December 14, 2014 7:30 pm Clinton Central Schools Performing Arts Complex The Greater Utica Choral Society presents the Clinton Symphony Orchestra The Greater Utica Choral Society is proud to sponsor the newly formed Clinton Symphony Orchestra in its inaugural concert. We are very excited to launch this new performing arts group whose mission will be to perform live symphonic repertoire of many different styles ranging from the Baroque era to the twenty-first century. Local musi- cians are most eager to perform in the wonderful acoustical venue of the Clinton Performing Arts Complex and hope that this concert will usher in a new a new renaissance of classical music. We would like to thank the many local citizens and businesses who have stepped up to support us. Dr. Roger Moore, President Mr. Charles Schneider, Music Director Ms. Marilee Ensign, General Manager Music Librarian: Rayna Schneider Program Ads: Barbara Kamp, Dana Schneider and Eli England Program Book: Marilee Ensign Printer: Express Printing CCS Theatre Manager: Keith DeStefanis Volunteers Clinton High School Orchestra Students Special Thank Yous Dr. & Mrs. Roger Moore Community Foundation of Herkimer and Oneida Counties Julia Scranton Clinton Central School District John Murphy Jack Murphy CHARLES SCHNEIDER, Music Director An award-winning and versatile musician, Maestro Schneider's experience spans the musical spectrum - Broadway musical theatre, opera, pops and symphonic music. He conducted the 1967 CBS Television Special of the Year with Jimmy Durante, The Supremes and Jimmy Dean. -

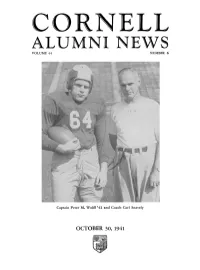

Alumni New Volume 44 Number 6

CORNELL ALUMNI NEW VOLUME 44 NUMBER 6 Captain Peter M. Wolff '42 and Coach Carl Snavely OCTOBER 30, 1941 LEHIGH VALLEY SERVICE Cornell for the Class Rings FOR WOMEN Dartmouth Ten carat gold mounting, set with sardonyx stone of Carnelian shade. Block "C" and numerals Game cut in the stone. ITHACA, SAT., NOV. IS $11.50 plus defense tax of 10% LOW ROUND TRIP FARES POSTPAID {Tax Not Included) FROM TO ITHACA ROUND TRIP THE CORNELL CO-OP Coach Travel Pullman Travel BARNES HALL ITHACA, N.Y. New York $ 8.95 AS13.10 BS14.60 Newark 8.70 A 12.75 B 14.20 Philadelphia 10.00 A 14.55 B 16.20 Rochester 3.60 Buffalo 5.55 A—Plus Cost of Upper Berth, each way. B—Plus Cost of Lower Berth, Room or Parlor Car Seat, Each Way. EAT COMFORTABLY Lower Berth $2.10, Upper $1.45, Parlor Car Seat $1.50. Double Bedroom ($2 or more) $4.20. Compartment (2 or more) $6.30, Drawing Room (2 or more) $7.35, each way (Tax not included.) Before the Game GOING November 8 Lv. New York (Penna. Station) 11:05 A.M. 10:10 P.M. Lv. Newark (Penna. Station) 11:20 A.M. 10:25 P.M. Lv. Philadelphia (Reading Ter.) 11:15 A.M. 10:35 P.M. Experienced Cornelliαns know Ar. Ithaca 6:41 P.M. x 7:38 A.M. that on a big game day, it's xSleeping Cars from New York may be occupied at Ithaca until 8:00 A.M. best to meet their Friends at the RETURNING University's Lv.