Oligodendroglial Epigenetics, from Lineage Specification to Activity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activation of ATM Depends on Chromatin Interactions Occurring Before Induction of DNA Damage

LETTERS Activation of ATM depends on chromatin interactions occurring before induction of DNA damage Yong-Chul Kim1,6, Gabi Gerlitz1,6, Takashi Furusawa1, Frédéric Catez1,5, Andre Nussenzweig2, Kyu-Seon Oh3, Kenneth H. Kraemer3, Yosef Shiloh4 and Michael Bustin1,7 Efficient and correct responses to double-stranded breaks the KAP-1 protein9. The local and global changes in chromatin organiza- (DSB) in chromosomal DNA are crucial for maintaining genomic tion facilitate recruitment of damage-response proteins and remodelling stability and preventing chromosomal alterations that lead to factors, which further modify chromatin in the vicinity of the DSB and cancer1,2. The generation of DSB is associated with structural propagate the DNA damage response. Given the extensive changes in chro- changes in chromatin and the activation of the protein kinase matin structure associated with the DSB response, it could be expected ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM), a key regulator of the that architectural chromatin-binding proteins, such as the high mobility signalling network of the cellular response to DSB3,4. The group (HMG) proteins, would be involved in this process10–12. interrelationship between DSB-induced changes in chromatin HMG is a superfamily of nuclear proteins that bind to chromatin architecture and the activation of ATM is unclear4. Here we show without any obvious specificity for a particular DNA sequence and affect that the nucleosome-binding protein HMGN1 modulates the the structure and activity of the chromatin fibre10,12,13. We have previ- interaction of ATM with chromatin both before and after DSB ously reported that HMGN1, an HMG protein that binds specifically to formation, thereby optimizing its activation. -

Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8+ T Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 25, 2021 T + is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology , 34 of which you can access for free at: 2016; 197:1477-1488; Prepublished online 1 July from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication 2016; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600589 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/4/1477 Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8 Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model Katherine A. Waugh, Sonia M. Leach, Brandon L. Moore, Tullia C. Bruno, Jonathan D. Buhrman and Jill E. Slansky J Immunol cites 95 articles Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2016/07/01/jimmunol.160058 9.DCSupplemental This article http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/4/1477.full#ref-list-1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material References Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2016 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 25, 2021. The Journal of Immunology Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8+ T Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model Katherine A. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond

cells Review Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond Sarah Kuhn y, Laura Gritti y, Daniel Crooks and Yvonne Dombrowski * Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (L.G.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0044-28-9097-6127 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 7 November 2019; Published: 12 November 2019 Abstract: Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS) that are generated from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC). OPC are distributed throughout the CNS and represent a pool of migratory and proliferative adult progenitor cells that can differentiate into oligodendrocytes. The central function of oligodendrocytes is to generate myelin, which is an extended membrane from the cell that wraps tightly around axons. Due to this energy consuming process and the associated high metabolic turnover oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to cytotoxic and excitotoxic factors. Oligodendrocyte pathology is therefore evident in a range of disorders including multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Deceased oligodendrocytes can be replenished from the adult OPC pool and lost myelin can be regenerated during remyelination, which can prevent axonal degeneration and can restore function. Cell population studies have recently identified novel immunomodulatory functions of oligodendrocytes, the implications of which, e.g., for diseases with primary oligodendrocyte pathology, are not yet clear. Here, we review the journey of oligodendrocytes from the embryonic stage to their role in homeostasis and their fate in disease. We will also discuss the most common models used to study oligodendrocytes and describe newly discovered functions of oligodendrocytes. -

Build a Neuron

Build a Neuron Objectives: 1. To understand what a neuron is and what it does 2. To understand the anatomy of a neuron in relation to function This activity is great for ALL ages-even college students!! Materials: pipe cleaners (2 full size, 1 cut into 3 for each student) pony beads (6/student Introduction: Little kids: ask them where their brain is (I point to my head and torso areas till they shake their head yes) Talk about legos being the building blocks for a tower and relate that to neurons being the building blocks for your brain and that neurons send messages to other parts of your brain and to and from all your body parts. Give examples: touch from body to brain, movement from brain to body. Neurons are the building blocks of the brain that send and receive messages. Neurons come in all different shapes. Experiment: 1. First build soma by twisting a pipe cleaner into a circle 2. Then put a 2nd pipe cleaner through the circle and bend it over and twist the two strands together to make it look like a lollipop (axon) 3. take 3 shorter pipe cleaners attach to cell body to make dendrites 4. add 6 beads on the axon making sure there is space between beads for the electricity to “jump” between them to send the signal super fast. (myelin sheath) 5. Twist the end of the axon to make it look like 2 feet for the axon terminal. 6. Make a brain by having all of the neurons “talk” to each other (have each student hold their neuron because they’ll just throw them on a table for you to do it.) messages come in through the dendrites and if its a strong enough electrical change, then the cell body sends the Build a Neuron message down it’s axon where a neurotransmitter is released. -

Id4: an Inhibitory Function in the Control

Id4: an inhibitory function in the control of hair cell formation? Sara Johanna Margarete Weber Thesis submitted to the University College London (UCL) for the degree of Master of Philosophy The work presented in this thesis was conducted at the UCL Ear Institute between September 23rd 2013 and October 19th 2015. 1st Supervisor: Dr Nicolas Daudet UCL Ear Institute, London, UK 2nd Supervisor: Dr Stephen Price UCL Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, London, UK 3rd Supervisor: Prof Guy Richardson School of Life Sciences, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK I, Sara Weber confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Heidelberg, 08.03.2016 ………………………….. Sara Weber 2 Abstract Mechanosensitive hair cells in the sensory epithelia of the vertebrate inner ear are essential for hearing and the sense of balance. Initially formed during embryological development they are constantly replaced in the adult avian inner ear after hair cell damage and loss, while practically no spontaneous regeneration occurs in mammals. The detailed molecular mechanisms that regulate hair cell formation remain elusive despite the identification of a number of signalling pathways and transcription factors involved in this process. In this study I investigated the role of Inhibitor of differentiation 4 (Id4), a member of the inhibitory class V of bHLH transcription factors, in hair cell formation. I found that Id4 is expressed in both hair cells and supporting cells of the chicken and the mouse inner ear at stages that are crucial for hair cell formation. -

Epigenetic Mechanisms of Lncrnas Binding to Protein in Carcinogenesis

cancers Review Epigenetic Mechanisms of LncRNAs Binding to Protein in Carcinogenesis Tae-Jin Shin, Kang-Hoon Lee and Je-Yoel Cho * Department of Biochemistry, BK21 Plus and Research Institute for Veterinary Science, School of Veterinary Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea; [email protected] (T.-J.S.); [email protected] (K.-H.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-02-800-1268 Received: 21 September 2020; Accepted: 9 October 2020; Published: 11 October 2020 Simple Summary: The functional analysis of lncRNA, which has recently been investigated in various fields of biological research, is critical to understanding the delicate control of cells and the occurrence of diseases. The interaction between proteins and lncRNA, which has been found to be a major mechanism, has been reported to play an important role in cancer development and progress. This review thus organized the lncRNAs and related proteins involved in the cancer process, from carcinogenesis to metastasis and resistance to chemotherapy, to better understand cancer and to further develop new treatments for it. This will provide a new perspective on clinical cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Abstract: Epigenetic dysregulation is an important feature for cancer initiation and progression. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcripts that stably present as RNA forms with no translated protein and have lengths larger than 200 nucleotides. LncRNA can epigenetically regulate either oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes. Nowadays, the combined research of lncRNA plus protein analysis is gaining more attention. LncRNA controls gene expression directly by binding to transcription factors of target genes and indirectly by complexing with other proteins to bind to target proteins and cause protein degradation, reduced protein stability, or interference with the binding of other proteins. -

HMGB1 in Health and Disease R

Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Journal Articles Academic Works 2014 HMGB1 in health and disease R. Kang R. C. Chen Q. H. Zhang W. Hou S. Wu See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles Part of the Emergency Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Kang R, Chen R, Zhang Q, Hou W, Wu S, Fan X, Yan Z, Sun X, Wang H, Tang D, . HMGB1 in health and disease. 2014 Jan 01; 40():Article 533 [ p.]. Available from: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles/533. Free full text article. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works. Authors R. Kang, R. C. Chen, Q. H. Zhang, W. Hou, S. Wu, X. G. Fan, Z. W. Yan, X. F. Sun, H. C. Wang, D. L. Tang, and +8 additional authors This article is available at Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles/533 NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Mol Aspects Med. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 December 01. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Mol Aspects Med. 2014 December ; 0: 1–116. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2014.05.001. HMGB1 in Health and Disease Rui Kang1,*, Ruochan Chen1, Qiuhong Zhang1, Wen Hou1, Sha Wu1, Lizhi Cao2, Jin Huang3, Yan Yu2, Xue-gong Fan4, Zhengwen Yan1,5, Xiaofang Sun6, Haichao Wang7, Qingde Wang1, Allan Tsung1, Timothy R. -

Neurons – Is a Basic Cell of the Nervous System. • Neurons Carry Nerve Messages, Or Impulses, from One Part of the Body to Another

Nervous System Nerves and Nerve Cells: Neurons – is a basic cell of the nervous system. • Neurons carry nerve messages, or impulses, from one part of the body to another. Structure of a Nerve Cell: A neuron has three basic parts: 1. Body – controls the cell’s growth 2. Axon – is a long thin fiber that carries impulses away from the cell body Myelin – is a fatty material that insulates the axon and increases the speed at which an impulse travels 3. Dendrites – are short, branching fibers that carry nerve impulses toward the cell body. • A nerve impulse begins when the dendrites are stimulated. The impulse travels along the dendrites to the cell body, and then away from the cell body on the axon. • The impulse must cross a synapse to a muscle or another neuron. Synapse – is the space between an axon and the structure with which the neuron communicates. Types of Nerve Cells: Sensory Neurons – pick up information about your external and internal environment from your sense organs and your body Motor Neurons – sends impulses to your muscles and glands, causing them to react Interneurons – are located only in the brain and spinal cord, pass impulses from one neuron to another The Central Nervous System: • The nervous system consists of two parts. Your brain and spinal cord make up one part, which is called the central nervous system. 1 • The peripheral nervous system, which is the other part, is made up of all the nerves that connect the brain and spinal cord to other parts of the body. The Brain: Brain ± a moist, spongy organ weighing about three pounds is made up of billions of neurons that control almost everything you do and experience. -

Artificial Induction of Sox21 Regulates Sensory Cell Formation in the Embryonic Chicken Inner Ear

Artificial Induction of Sox21 Regulates Sensory Cell Formation in the Embryonic Chicken Inner Ear Stephen D. Freeman*, Nicolas Daudet* UCL Ear Institute, University College London, London, United Kingdom Abstract During embryonic development, hair cells and support cells in the sensory epithelia of the inner ear derive from progenitors that express Sox2, a member of the SoxB1 family of transcription factors. Sox2 is essential for sensory specification, but high levels of Sox2 expression appear to inhibit hair cell differentiation, suggesting that factors regulating Sox2 activity could be critical for both processes. Antagonistic interactions between SoxB1 and SoxB2 factors are known to regulate cell differentiation in neural tissue, which led us to investigate the potential roles of the SoxB2 member Sox21 during chicken inner ear development. Sox21 is normally expressed by sensory progenitors within vestibular and auditory regions of the early embryonic chicken inner ear. At later stages, Sox21 is differentially expressed in the vestibular and auditory organs. Sox21 is restricted to the support cell layer of the auditory epithelium, while it is enriched in the hair cell layer of the vestibular organs. To test Sox21 function, we used two temporally distinct gain-of-function approaches. Sustained over- expression of Sox21 from early developmental stages prevented prosensory specification, and abolished the formation of both hair cells and support cells. However, later induction of Sox21 expression at the time of hair cell formation in organotypic cultures of vestibular epithelia inhibited endogenous Sox2 expression and Notch activity, and biased progenitor cells towards a hair cell fate. Interestingly, Sox21 did not promote hair cell differentiation in the immature auditory epithelium, which fits with the expression of endogenous Sox21 within mature support cells in this tissue. -

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association Between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic Asthma Ayoung Jeong 1,2, Medea Imboden 1,2, Akram Ghantous 3, Alexei Novoloaca 3, Anne-Elie Carsin 4,5,6, Manolis Kogevinas 4,5,6, Christian Schindler 1,2, Gianfranco Lovison 7, Zdenko Herceg 3, Cyrille Cuenin 3, Roel Vermeulen 8, Deborah Jarvis 9, André F. S. Amaral 9, Florian Kronenberg 10, Paolo Vineis 11,12 and Nicole Probst-Hensch 1,2,* 1 Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, 4051 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] (A.J.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 Department of Public Health, University of Basel, 4001 Basel, Switzerland 3 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 69372 Lyon, France; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (Z.H.); [email protected] (C.C.) 4 ISGlobal, Barcelona Institute for Global Health, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (A.-E.C.); [email protected] (M.K.) 5 Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08002 Barcelona, Spain 6 CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), 08005 Barcelona, Spain 7 Department of Economics, Business and Statistics, University of Palermo, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 8 Environmental Epidemiology Division, Utrecht University, Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, 3584CM Utrecht, Netherlands; [email protected] 9 Population Health and Occupational Disease, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, SW3 6LR London, UK; [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (A.F.S.A.) 10 Division of Genetic Epidemiology, Medical University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] 11 MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, W2 1PG London, UK; [email protected] 12 Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine (IIGM), 10126 Turin, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-61-284-8378 Int. -

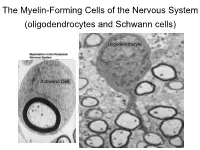

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes