Humour and Heterotopias in the Works of Edward Gorey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Beatrix Potter Admirers, Society News the Beatrix Potter Society

Approaching "Beatrix's side" of Windermere, on the ferry from Bowness Photo: J. Sullivan Dear Beatrix Potter Admirers, The Beatrix Potter Welcome back to another mix of articles, events and Society happenings - it is always an adventure to see where Beatrix will take us! Interested in learning more about Beatrix Potter? Consider joining the Society News Society. Meet others who are passionate about The Society's Committee, following the AGM in early March: Beatrix Potter, her life and works. You will also receive the quarterly Journal and Newsletter, full of interesting articles about Miss Potter and the Society's efforts and events. Find the Membership form for download, and more information about the Society here. Save the Date: May 20, 2017: Spring Meeting, Sloane Club, London. Rear row, l to r: Angela Black, Meetings Secretary; Miranda Gore Browne; Sue Smith, Treasurer; Helen Duder, Archivist and merchandise specialist. June 9-11, 2017: Front row, l to r: Rowena Godfrey, Chairman; Kathy Cole, Secretary Photo: Betsy Bray "Beatrix Potter in New London on the Thames River: A Symposium at the Linda Lear Center for The Society is still looking for Members to take over the roles Special Collections and of Treasurer, Sales Manager, and Editor of the Journal and Archives", Connecticut Newsletter, as well as someone to help create publications. If College, New London, CT. you can volunteer, please contact [email protected]. September 9-10, 2017: Autumn Meeting, Lake District, UK. December 2, 2017: Festive Gathering, Sloane Club, London. Quick Links Email us at: [email protected] m Read the previous issue of "Pottering About" here. -

Guided Reading Level I

Guided Reading Book List It can be difficult finding books that meet your child's reading ability. Below is a list of suggested books according to their guided reading level. Guided Reading Level I Airport by Byron Barton Albert the Albatross by Syd Hoff Allergies by Sharon Gordon All Tutus Should Be Pink by Sheri Brownrigg Alligators All around by Maurice Sendak Ambulances by Marcia Freeman Angus and the Cat by Marjorie Flack Apples and Pumpkins by Ann Rockwell Are You My Mother? by P.D. Eastman Asthma by Sharon Gordon The Bear’s Bicycle by Emilie McLeod Benny Bakes a Cake by Eve Rice Big Dog, Little Dog by P.D. Eastman The Big Hungry Bear by Don and Audrey Wood The Bike Lesson by Stan and Jan Berenstain Busy Buzzing Bumblebees by Alvin Schwartz Charles M. Schulz by Cheryl Carlson Come and Have Fun by Edith Thacher Hurd The Dinosaur Who Lived in My Backyard by Brendan Hennessy Dragon Gets By by Dav Pilkey Dragon’s Fat Cat by Dav Pilkey Earaches by Sharon Gordon Father Bear Comes Home by Else Minarik Fire Engines by Marcia Freeman A Friend for Dragon by Dav Pilkey Go away, Dog by Joan Nodset Goodnight, Owl! by Pat Hutchins Hattie and the Fox by Mem Fox Hello Cat, You Need a Hat by Rita Gelman Henny Penny by Paul Galdone Hiccups for Elephant by James Preller It’s Not Easy Being a Bunny by Marilyn Sadler Jim Meets the Thing by Miriam Cohen Just a Mess by Mercer Mayer Leo the Late Bloomer by Robert Kraus The Lighthouse Children by Syd Hoff A Look at China by Helen Frost A Look at Mexico by Helen Frost Lost in the Museum by Miriam Cohen Maurice -

American Masters 200 List Finaljan2014

Premiere Date # American Masters Program Title (Month-YY) Subject Name 1 ARTHUR MILLER: PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS On the Set of "Death of a Salesman" June-86 Arthur Miller 2 PHILIP JOHNSON: A SELF PORTRAIT June-86 Philip Johnson 3 KATHERINE ANNE PORTER: THE EYE OF MEMORY July-86 Katherine Anne Porter 4 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 1) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 5 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 2) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 6 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 3) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 7 BILLIE HOLIDAY: THE LONG NIGHT OF LADY DAY August-86 Billie Holiday 8 JAMES LEVINE: THE LIFE IN MUSIC August-86 James Levine 9 AARON COPLAND: A SELF PORTRAIT August-86 Aaron Copland 10 THOMAS EAKINS: A MOTION PORTRAIT August-86 Thomas Eakins 11 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE September-86 Georgia O'Keeffe 12 EUGENE O'NEILL: A GLORY OF GHOSTS September-86 Eugene O'Neill 13 ISAAC IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER July-87 Isaac Bashevis Singer 14 DIRECTED BY WILLIAM WYLER July-87 William Wyler 15 ARTHUR RUBENSTEIN: RUBENSTEIN REMEMBERED July-87 Arthur Rubinstein 16 ALWIN NIKOLAIS AND MURRAY LOUIS: NIK AND MURRAY July-87 Alwin Nikolais/Murray Louis 17 GEORGE GERSHWIN REMEMBERED August-87 George Gershwin 18 MAURICE SENDAK: MON CHER PAPA August-87 Maurice Sendak 19 THE NEGRO ENSEMBLE COMPANY September-87 Negro Ensemble Co. 20 UNANSWERED PRAYERS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF TRUMAN CAPOTE September-87 Truman Capote 21 THE TEN YEAR LUNCH: THE WIT AND LEGEND OF THE ALGONQUIN ROUND TABLE September-87 Algonquin Round Table 22 BUSTER KEATON: A HARD ACT TO FOLLOW (Part 1) November-87 Buster Keaton 23 BUSTER KEATON: -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

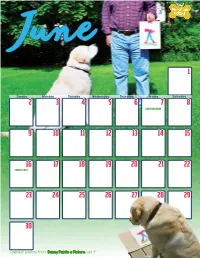

Calendar Photos from Danny Paints a Picture, Set 4 June 2019 Cut and Paste Activity Calendar Activity

June 1 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dad’s birthDay 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Father’s Day 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Calendar photos from Danny Paints a Picture, set 4 June 2019 Cut and Paste Activity Calendar Activity Find the June birthdays, cut out the picture that goes with each, and paste it on their special day on the calendar. 6 Cynthia Rylant was born June 6, 1954 in West Virginia. Her youth in the Appalachian region provided the setting for her first children’s book, When I was Young in the Mountains. A prolific writer of children’s literature, Rylant explores themes of friendship, emotions, and growing up. She has been awarded the Newbery Medal for A Fine White Dust, and several other stories have been named Newbery Honor and Caldecott Honor books. 10 The writer and illustrator of the popular Where the Wild Things Are, Maurice Sendak was born June 10, 1928. First an illustrator, Sendak worked on more than eighty books written by various authors before he wrote his own story. Kenny’s Window, published in 1956, was Sendak’s first title of which he was both author and illustrator. Seven years later he produced Where the Wild Things Are and earned the Caldecott Medal. 18 Another Caldecott Medal winner is Chris Van Allsburg. Born June 18, 1949, Allsburg is best known as the author and illustrator of Jumanji and The Polar Express, both of which have been made into major motion pictures. -

1 Abbey Books; #4 Richard Abel Bookseller; 1973:1, S

M-106 BOOKSELLER’S CATALOGS A & R BOOKSELLERS; #1 ABACUS BOOKSHOP; #1 ABBEY BOOKS; #4 RICHARD ABEL BOOKSELLER; 1973:1, Sale edition; 1974: 1 ABI BOOKS; #10-11, 15, 22-23, 30; Edward Gordon Craig; 1982: Early autumn, Spring, Edward Gorey; 1983: Spring ABINGTON BOOKS; 1973: Autumn ABOUT BOOKS; #3, 9-10, 61-64, 67-69 BEN ABRAHMSON’S ARGUS BOOK SHOP; #1-5, 7-12, 14-17, 20-34, Along the north wall, Along the south wall, 383, 623, 626, 969, 975, 985, 1944: Oct. HERMAN ABROMSON; #5-6, 7-10, 12 ACADEMIC BOOK COLLECTION; #9 ACADEMY BOOK SHOP; #61 PAUL ADAMS; Botany ADCO SPORTS BOOK EXCHANGE; 1808 TO DATE RICHARD ADAMIAK; #29 RICHARD H. ADELSON; 1981: Spring ; 1983: Spring ; 1992-93: Winter; 1994-95: Winter ADS AUTOGRAPHS; #1-3, 6-10, 13 ADVENTURE BOOK STORE; #1 ; 1988: Nov. AEONIAN PRESS; 1 catalog (unnumbered/undated) AESOP BOOKS; #8 CHARLES AGVENT; #2-5 AHAB RARE BOOKS; #26-27 ALASTOR RARE BOOKS; #16 EDWIN ALBERT; #1 l ALBION BOOKS; #3-4; 1979: Dec. ALCAZAR BOOK SERVICE; #51, 156 ALDREDGE BOOK STORE; #53, 87, 89-90, 114-116 ALEX ALEC-SMITH; #10, 14/16, 18 ALEPH-BET BOOKS; #3, 8-12, 14, 32, 35, 38-41, 43-45, 49, 53, 65; 2004: April 19 ALEXANDERSON & KLOSINSKI BOOKSELLERS; #1-2 ALFA ANTIQUARIAN BOOKSELLER; #79 LIBRAIRIE ALIX; #1 D.C. ALLEN; #32-33, 36, 58, 60, 62 R.R. ALLEN BOOKS; #21, 66-67, 70, 74, 79, 81-82, 84, 86, 92-96; 1996 WILLIAM H. ALLEN BOOKSELLER; #189, 206, 219, 224-225, 227-228, 231-232, 235-236, 239, 244-245, 249-251, 254-256, 259-261, 264-266, 268, 271-273, 275-276, 279-281, 283-284, 287-288, 290-291, 293- 294, 296-297, 300-301, 303-305, 307, 310-311, 313-314, 316-318, 320-321, 323-324; Special mailing 20 DUNCAN M. -

Hail to the Caldecott!

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 11 Number 1 Spring 2013 ISSN 1542-9806 Hail to the Caldecott! Interviews with Winners Selznick and Wiesner • Rare Historic Banquet Photos • Getting ‘The Call’ PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT PENGUIN celebrates 75 YEARS of the CALDECOTT MEDAL! PENGUIN YOUNG READERS GROUP PenguinClassroom.com PenguinClassroom PenguinClass Table Contents● ofVolume 11, Number 1 Spring 2013 Notes 50 Caldecott 2.0? Caldecott Titles in the Digital Age 3 Guest Editor’s Note Cen Campbell Julie Cummins 52 Beneath the Gold Foil Seal 6 President’s Message Meet the Caldecott-Winning Artists Online Carolyn S. Brodie Danika Brubaker Features Departments 9 The “Caldecott Effect” 41 Call for Referees The Powerful Impact of Those “Shiny Stickers” Vicky Smith 53 Author Guidelines 14 Who Was Randolph Caldecott? 54 ALSC News The Man Behind the Award 63 Index to Advertisers Leonard S. Marcus 64 The Last Word 18 Small Details, Huge Impact Bee Thorpe A Chat with Three-Time Caldecott Winner David Wiesner Sharon Verbeten 21 A “Felt” Thing An Editor’s-Eye View of the Caldecott Patricia Lee Gauch 29 Getting “The Call” Caldecott Winners Remember That Moment Nick Glass 35 Hugo Cabret, From Page to Screen An Interview with Brian Selznick Jennifer M. Brown 39 Caldecott Honored at Eric Carle Museum 40 Caldecott’s Lost Gravesite . -

VINTAGE POSTERS FEBRUARY 25 Our Annual Winter Auction of Vintage Posters Features an Exceptional Selection of Rare and Important Art Nouveau Posters

SCALING NEW HEIGHTS There is much to report from the Swann offices these days as new benchmarks are set and we continue to pioneer new markets. Our fall 2013 season saw some remarkable sales results, including our top-grossing Autographs auction to date—led by a handwritten Mozart score and a collection of Einstein letters discussing his general theory of relativity, which brought $161,000 each. Check page 7 for more post-sale highlights from the past season. On page 7 you’ll also find a brief tribute to our beloved Maps specialist Gary Garland, who is retiring after nearly 30 years with Swann, and the scoop on his replacement, Alex Clausen. Several special events are in the works for our winter and spring sales, including a talk on the roots of African-American Fine Art that coincides with our February auction, a partnership with the Library Company of Philadelphia and a discussion of the growing collecting field of vernacular photography. Make sure we have your e-mail address so you’ll receive our invites. THE TRUMPET • WINTER / SPRING 2014 • VOLUME 28, NUMBER 2 20TH CENTURY ILLUSTRATION JANUARY 23 Following the success of Swann’s first dedicated sale in this category, our 2014 auction features more excellent examples by famous names. There are magazine and newspaper covers and cartoons by R.O. Blechman, Jules Feiffer, David Levine, Ronald Searle, Edward Sorel, Richard Taylor and James Thurber, as well as works by turn-of-the-20th-century magazine and book illustrators such as Howard Chandler Christy and E.W. Kemble. Beloved children’s book artists include Ludwig Bemelmans, W.W. -

1998 Acquisitions

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in. -

Edward Gorey Phantasmagorey, 1974 Pen and Ink with Collage on Paper Collection of Clifford Ross

Edward Gorey Phantasmagorey, 1974 Pen and ink with collage on paper Collection of Clifford Ross Phantasmagorey is a play on the term “phantasmagoria” which means: “a constantly shifting, complex succession of things seen or imagined.” Like a phantasmagoria, this series of six images reveals dreamlike glimpses into Gorey’s imagination. Each vignette shows a common motif in Gorey’s work, including a ghostly femme fatale, a cat sitting atop a stack of books, and a fur-coated self-portrait. This drawing was made for an exhibition of the same name, held at the Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University, in 1974. An art student named Clifford Ross, now a contemporary artist in his own right, curated the first survey of Gorey’s work for his senior thesis. 501 Harry Benson Scottish, born 1929 Edward Gorey in His New York City Apartment with Cat, 1978 Gelatin silver print Collection of the artist Benson’s photographic portrait offers a glimpse into Gorey’s apartment in Manhattan’s Murray Hill neighborhood, where he lived from 1953 to 1983. Gorey displayed his collection of fine art—including a print by Edvard Munch and drawings by Balthus—next to found objects that he treated as works of art, such as a weathered crucifix and a needlepoint of a skull. Out and about in the city, he took in movies, theater, dance, and art exhibitions. At home, he retreated to his creative sanctuary filled with obscure books, fine art, and his beloved cats. Edvard Munch Norwegian, 1863–1944 The Woman and the Bear, 1908–9 Lithograph on wove paper mounted on wove paper Bequest of Edward Gorey, 2001.13.61 Munch created this image to illustrate his mythical story Alpha and Omega. -

Drawing on the Victorians Eries in Victorian Studies S Series Editors: Joseph Mclaughlin and Elizabeth Miller Katherine D

Drawing on the Victorians eries in Victorian Studies S Series editors: Joseph McLaughlin and Elizabeth Miller Katherine D. Harris, Forget Me Not: The Rise of the British Literary Annual, 1823–1835 Rebecca Rainof, The Victorian Novel of Adulthood: Plot and Purgatory in Fictions of Maturity Erika Wright, Reading for Health: Medical Narratives and the Nineteenth-Century Novel Daniel Bivona and Marlene Tromp, editors, Culture and Money in the Nineteenth Century: Abstracting Economics Anna Maria Jones and Rebecca N. Mitchell, editors, Drawing on the Victorians: The Palimpsest of Victorian and Neo-Victorian Graphic Texts Drawing on the Victorians The Palimpsest of Victorian and Neo-Victorian Graphic Texts edited by Anna Maria Jones and Rebecca N. Mitchell with an afterword by Kate Flint ohio university press athens Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701 ohioswallow.com © 2017 by Ohio University Press All rights reserved To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax). Printed in the United States of America Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ƒ ™ 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request. Names: Jones, Anna Maria, 1972- editor. | Mitchell, Rebecca N. (Rebecca Nicole), 1976- editor. Title: Drawing on the Victorians : the palimpsest of Victorian and neo-Victorian graphic texts / edited by Anna Maria Jones and Rebecca N. Mitchell ; with an afterword by Kate Flint. -

Wins DITMAR and ATHELING AWARDS Harlan Ellison Wins Fans at Syncon *83 BRUCE GILLESPIE to RECEIVE WORLD SF AWARD

Terry Dowling Wins DITMAR and ATHELING AWARDS Harlan Ellison Wins Fans At Syncon *83 BRUCE GILLESPIE TO RECEIVE WORLD SF AWARD TOE AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS - THE DITMARS, were presented at the 22nd Australian National Science Fiction Convention -SYNCON '83, which was held at the Shore Motel, Artarmon, Sydney, June 10-13. The highlight of this well organised convention, one of the best all round sf cons we have seen in Australia, was the showman like performance of the Guest of Honour, HARLAN ELLISON. He had all the fans practically eating out of his hands, with the colourful and dramatic style of his speech making, readings and conversation. Besides TERRY DOWLING, the inevitable two awards went to MARC ORTLIEB again and ROBIN JOHNSON received the Special Award for Services to Australian Science Fiction. The full list of winners is as follows: BEST INTERNATIONAL SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY RIDDLEY WALKER by Russell Hoban (Jonathan Cape / Pan J BEST AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY "The Man Who Walked Away Behind the Eyes" by Terry Dowling (OMEGA May/June '83 ) BEST AUSTRALIAN FANZINE BEST AUSTRALIAN FAN WRITER Q 36 Edited by Marc Ortlieb Marc Ortlieb BEST AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY ARTIST BRUCE GILLESPIE & ELAINE COCHRANE (Photo John Litchen) Marilyn Pride Melbourne fan and publisher BRUCE GILLESPIE has been awarded the World SF organisation's BEST AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY CARTOONIST "Harrison Award" for Increasing the Status John Packer of Science Fiction Internationally. Two other recipients of this award were Sam Lundwell BEST AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY EDITOR and Krsto Mazuranic.