Lester Bird V Baldwin Spencer Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antigua and Barbuda an Annotated Critical Bibliography

Antigua and Barbuda an annotated critical bibliography by Riva Berleant-Schiller and Susan Lowes, with Milton Benjamin Volume 182 of the World Bibliographical Series 1995 Clio Press ABC Clio, Ltd. (Oxford, England; Santa Barbara, California; Denver, Colorado) Abstract: Antigua and Barbuda, two islands of Leeward Island group in the eastern Caribbean, together make up a single independent state. The union is an uneasy one, for their relationship has always been ambiguous and their differences in history and economy greater than their similarities. Barbuda was forced unwillingly into the union and it is fair to say that Barbudan fears of subordination and exploitation under an Antiguan central government have been realized. Barbuda is a flat, dry limestone island. Its economy was never dominated by plantation agriculture. Instead, its inhabitants raised food and livestock for their own use and for provisioning the Antigua plantations of the island's lessees, the Codrington family. After the end of slavery, Barbudans resisted attempts to introduce commercial agriculture and stock-rearing on the island. They maintained a subsistence and small cash economy based on shifting cultivation, fishing, livestock, and charcoal-making, and carried it out under a commons system that gave equal rights to land to all Barbudans. Antigua, by contrast, was dominated by a sugar plantation economy that persisted after slave emancipation into the twentieth century. Its economy and goals are now shaped by the kind of high-impact tourism development that includes gambling casinos and luxury hotels. The Antiguan government values Barbuda primarily for its sparsely populated lands and comparatively empty beaches. This bibliography is the only comprehensive reference book available for locating information about Antigua and Barbuda. -

The Antigua and Barbuda Review of Books

VOLUME 12 THE ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA REVIEW OF BOOKS NUMBER 1 Rev. Birchfield Aymer on St. Luke Dorbrene O’Marde on Barbuda Lionel Hurst on Barbuda Paget Henry on Barbuda Edgar O. Lake on Clement White Elaine Olaoye on Glenn Sankatsing SUMMER 2019 Elaine Jacobs on Clement White Poetry with Sir Lester Bird, Elaine Olaoye and Clement White And much more …. Produced by the Office of University Communications THE ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA REVIEW OF BOOKS A Publication of the Antigua and Barbuda Studies Association Volume 12 • Number 1 • Summer 2019 Copyright © 2019 Antigua and Barbuda Studies Association Editorial Board: Ian Benn, Joanne Hillhouse, Paget Henry, Edgar Lake, Adlai Murdoch, Ermina Osoba, Elaine Olaoye, Mali Olatunji, Vincent Richards Paget Henry, Editor The Antigua and Barbuda Studies Association was founded in 2006 with the goal of raising local intellectual awareness by creating a field of Antigua and Barbuda Studies as an integral part of the larger field of Caribbean Studies. The idea for such an interdisciplinary field grew out of earlier “island conferences” that had been organized by the University of the West Indies, School of Continuing Education, in conjunction with the Political Culture Society of Antigua and Barbuda. The Antigua and Barbuda Review of Books is an integral part of this effort to raise local and regional intellectual awareness by generating conversations about the neglected literary traditions of Antigua and Barbuda through reviews of its texts. Manuscripts: the manuscripts of this publication must be in the form of short reviews of books or works of art dealing with Antigua and Barbuda. -

The Antigua and Barbuda High Commission Official Newsletter

March/April/May 2013 The Antigua and Barbuda High Commission Official Newsletter A newsletter produced by the Antigua and Barbuda High Commission London for nationals and friends of Antigua and Barbuda Issue 153 Antigua hosts 57th during the session. the usual pomp and ceremo- Meeting of OECS Au- ny at the opening ceremony, The meeting agenda, for the on June 2 at which time the thority “Each business session on June 3 outgoing chairman of the Endeavour- ing all Achieving” Inside This Issue Commonwealth 5 Day Observance Prime Minister 6 Appoints New Senators Heads of Government of the and 4, included mulling the Authority, Prime Minis- Walker retains 7 Organisation of Eastern Car- financial landscape and the ter of St. Vincent and the BMP Leadership ibbean States (OECS) and OECS development strategy. Grenadines Dr. Ralph their national delegations Barbuda First 8 Gonsalves, handed over gathered in Antigua, from Calypso Tent The heads also engaged the the reins to Prime Minis- June 2 to 4, for the 57th private sector, as they con- ter Baldwin Spencer. Coco Point Beach Meeting of the OECS Au- 9 sidered a partnership for Barbuda thority. growth and development. Both the opening and the A Little Bit about 13 Work programmes and business sessions will be held Rosie The Authority comprised of budgets of the organs of the at Sandals Grande Antigua prime ministers and chief OECS were to be examined. Resort and Spa, at Dickenson Barbuda Express 16 ministers. The supreme poli- Bay. cy-making body in the sub- Before the leaders got down Update on New 18 regional grouping, continue Airport to work, however, there was 28th May 2013 to advance Economic Union * * * * * * Kite Surfing Festi- 20 val Antigua Carnival Saturday 27th July to Tuesday 6th August 2013 Antigua and Barbuda High Commission, 2nd Floor, 45 Crawford Place, London W1H 4LP Telephone:020 7258 0070 Facsimile:020 7258 7486 Email: [email protected] 2 High Commissioner‘s Message Address by H.E. -

United States District Court Northern District of Texas Dallas Division

Case 3:12-cv-04641-L Document 1 Filed 11/15/12 Page 1 of 172 PageID 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION RALPH S. JANVEY, in his capacity § as court-appointed receiver for the § Stanford receivership estate; § The OFFICIAL STANFORD § INVESTORS COMMITTEE; § SANDRA DORRELL; § SAMUEL TROICE; and § MICHOACAN TRUST; individually § and on behalf of a class of all others § similarly situated § § Plaintiffs § CIVIL ACTION NO. _________ § VS. § § GREENBERG TRAURIG, LLP; § HUNTON & WILLIAMS, LLP; and § YOLANDA SUAREZ § § Defendants § PLAINTIFFS’ ORIGINAL COMPLAINT - CLASS ACTION 1 Case 3:12-cv-04641-L Document 1 Filed 11/15/12 Page 2 of 172 PageID 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PARTIES ........................................................................................................................... 2 II. OVERVIEW OF CASE .................................................................................................... 4 III. PERSONAL JURISDICTION ......................................................................................... 7 IV. SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION & VENUE ...................................................... 8 V. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... 8 A. The Stanford Financial Group Empire .................................................................... 8 B. Stanford Financial’s Operations in the United States and Texas Base ................. 10 C. The Anatomy of the Stanford Illicit Securities Scheme ....................................... -

13 Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda | Freedom House Page 1 of 1 JOIN OUR MAILING LIST About Us DONATE Blog Contact Us Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Donate FREEDOM OF THE PRESS - View another year - Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda Freedom of the Press 2013 - Select year - The constitution provides for freedoms of speech and of the press, but the government enforces those rights somewhat selectively. Defamation remains a criminal offense, punishable by up to three years in prison. Cases 2013 SCORES are occasionally brought against journalists, and politicians often file libel suits against opposing party members. In February 2012, a court ruled in favor of opposition Antigua Labour Party (ALP) leader Lester Bird in a PRESS STATUS defamation case against Prime Minister Baldwin Spencer and Crusader Radio, owned by the ruling United Progressive Party (UPP), for statements Spencer made during a 2008 campaign rally that were aired by the Partly station. The judge awarded EC$75,000 (US$28,000) in damages to Bird, and declared that radio stations would be held responsible for defamatory comments made during live broadcasts without a time delay. In August, a Free controversial song to be played during the annual Carnival, which some claimed celebrated violence against PRESS FREEDOM SCORE women, led to calls for the establishment of a broadcast commission to monitor the country’s airwaves. The proposal received government support, but a commission had yet to be created by year’s end. 38 The 2004 Freedom of Information Act grants citizens the right to access official government documents and established a commissioner to oversee compliance, though Antiguans have complained of difficulties in obtaining LEGAL ENVIRONMENT information. -

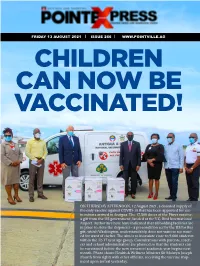

ON THURSDAY AFTERNOON, 12 August 2021, a Donated Supply of the Only Vaccine Against COVID-19 That Has Been Approved for Use in Minors Arrived in Antigua

FRIDAY 13 AUGUST 2021 | ISSUE 266 | WWW.POINTVILLE.AG CHILDREN CAN NOW BE VACCINATED! ON THURSDAY AFTERNOON, 12 August 2021, a donated supply of the only vaccine against COVID-19 that has been approved for use in minors arrived in Antigua. The 17,500 doses of the Pfizer vaccine, a gift from the US government, landed at the V.C. Bird International Airport. Authorities here have indicated that all holding facilities are in place to store the shipment – a precondition set by the US for this gift, which Washington, understandably, does not want to see wast- ed for want of shelter. The aim is to inoculate close to 9,000 students within the 12-17 year age group. Consultations with parents, teach- ers and school administrators are planned so that the students can be vaccinated before the new semester/academic year begins next month. Photo shows Health & Wellness Minister Sir Molwyn Joseph (fourth from right) with other officials, receiving the vaccine ship- ment upon arrival yesterday. WEDNESDAY 11 AUGUST 2021 PAGE 2 GUEST EDITORIAL Are people in the Caribbean becoming architects of their own destruction? (The writer is An- tigua and Barbuda’s Ambassador to the United States and the Organization of American States. He is also a Senior Fel- low at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies at the Uni- versity of London and Massey College in the University of Toronto. The views expressed are entirely his own) The question has to be asked: Are some people in Caribbean countries becoming the architects of their own, and the region’s, destruction? There is clearly an organised anti-vac- cination campaign throughout the re- gion. -

Newsletter 135-Jly Aug

The Antigua and Barbuda High Commission Official Newsletter - Issue 135 -- July/August 2009 This is Carnival! by Andrea Thomas The lead up to Antigua’s Carnival since the beginning of June. This of what they could expect to hear, 2009 was jam packed with all well attended event previewed and see, over the carnival different events, the most the new and upcoming Antiguan season. popular being the Joe Mikes artists to the eager crowds that Jam session every Thursday gathered. This gave them a taste Continue on pages 19,20 Queen of Carnival (Shelana George) and her runners-up In This Issue 1. Prime Minister’s Emancipation Day Message (pages 3 & 7) 2. Antigua and Barbuda receives US$50 Million from Venezuela ( page 12) 3. Educational Past (page 18) 4. Carnival 2009 highlights (pages 1,19 & 20) Antigua and Barbuda High Commission Issue 135 - July/August 2009 a march on this basis. It may pride when one of their fellow citizens even be said that it is a does well at an international event citizen’s constitutional right to (for example Usain Bolt at the demonstrate to its recently concluded 12th IAAF World government how he/she feels Championship in Germany). Let me about prevailing issues in the quickly add, in case someone readily country. However, I was very reminds me, that our own Daniel surprised to hear of the Bailey performed exceptionally well. I presence of so many foreign know, I saw it and there I was flags being waved by beaming with so much pride as an marchers. -

The Failings of Governance in Antigua and Barbuda

THE FAILINGS OF GOVERNANCE IN ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA THE ELECTIONS OF 1999 Douglas W. Payne June 1, 1999 Policy Papers on the Americas THE FAILINGS OF GOVERNANCE IN ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA The Elections of 1999 Douglas W. Payne Policy Papers on the Americas Volume X Study 4 June 1, 1999 CSIS Americas Program The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), established in 1962, is a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS is dedicated to policy analysis and impact. It seeks to inform and shape selected policy decisions in government and the private sector to meet the increasingly complex and difficult global challenges that leaders will confront in the next century. It achieves this mission in three ways: by generating strategic analysis that is anticipatory and interdisciplinary, by convening policymakers and other influential parties to assess key issues, and by building structures for policy action. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author. CSIS Americas Program Leadership Georges Fauriol, Director M. Delal Baer, Deputy Director and Director, Mexico Project Amy Coughenour, Assistant Director Michael May, Director, MERCOSUR-South America Project Armand Peschard-Sverdrup, Assistant Director, Mexico Project Christopher Sands, Director, Canada Project Editor Joyce Hoebing, Adjunct Fellow © 1999 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. This report was prepared under the aegis of the CSIS Western Hemisphere Election Study series. Comments are welcome and should be directed to: Amy Coughenour CSIS Americas Program 1800 K Street, NW Washington, D.C. -

Trustworthiness and Jurisdiction in the Stanford Financial Group Fraud

Trustworthiness and Jurisdiction in the Stanford Financial Group Fraud by Camilo Arturo Leslie A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Margaret R. Somers, Co-Chair Professor George P. Steinmetz, Co-Chair Professor Donald J. Herzog Associate Professor Greta R. Krippner Associate Professor Geneviève Zubrzycki © Camilo Arturo Leslie 2015 DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my father, Camilo Antonio Leslie, and to the love, good humor, and perseverance of my mother, Lourdes Leslie. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This grueling, absurd, intermittently wonderful journey began a very long time ago, and I’ve racked up a list of debts appropriate to its duration. I arrived in Ann Arbor in the early 2000s without a plan or a clue, and promptly enrolled in a social theory course co-taught by George Steinmetz and Webb Keane. Both professors, and several graduate students enrolled in that course (Mucahit Bilici, Hiroe Saruya, John Thiels), were more welcoming than I had any right to expect, and my application to the sociology program the following year was largely in response to their generosity of spirit. Before long, I was enrolled as both a 1L at the University of Michigan Law School and as a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology. For their many forms of support and indispensable friendship during these trying first few years, I wish to thank the entire Horwitz family (Beth, Jeremy, Larry, and Tobi); Marco Rigau and Alexandra Carbone; and Ryan Calo and Jean Brownell. -

In the Eastern Caribbean: the Antigua–US WTO Internet Gambling Case

The Centre for International Governance Innovation THE CARIBBEAN PAPERS A Project on Caribbean Economic Governance “Remote” in the Eastern Caribbean: The Antigua–US WTO Internet Gambling Case ANDREW F. COOPER Caribbean Paper No.4 April 2008 An electronic version of this paper is available for download at: www.cigionline.org Addressing International Governance Challenges THE CARIBBEAN PAPERS Abstract Letter from the The structure of the multilateral trading system is widely Executive Director assumed to contain bias towards big actors, unevenly dis- tributing access to the key processes of the system. Small It is my pleasure to introduce The Caribbean countries, including Caribbean states, have long focused Papers, a product of our major research project on their attention on physical merchandise, while the US Caribbean Economic Governance. CIGI is an inde- has taken on the role of disciplinarian, confronting coun- pendent, nonpartisan think tank that addresses tries that they perceive to be in violation of the General international governance challenges. Led by a Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). group of experienced practitioners and distin- guished academics, CIGI supports research, Brought to the WTO by Antigua, the Internet remote gam- forms networks, advances policy debates, builds bling case has challenged standard assumptions about the capacity, and generates ideas for multilateral workings of the international trading system in the WTO governance improvements. context. A small country appearing to take the US on by itself, Antigua claimed the American government failed to This project convenes researchers and leaders live up to its commitment under GATS regarding “recre- within the private and public sectors to examine ational services.” While Antigua argued for fairness in the and provide substantive answers and policy pre- WTO system, the US adopted a prohibitionist attitude to scription to current economic governance chal- Internet remote gambling, citing domestic moral standards. -

Newsletter101 ( .Pdf )

ISSUE No.101 July 2005 n 5th July, Prime Minister Baldwin Spencer O presented his government’s case to the Heads of CARICOM for the retention of work permits for non- nationals after the implementation of the CSME in December 2005. Antigua and Barbuda was granted derogation by the Heads in July of 2002 from the requirement to fully implement the free movement of skills regime; and was allowed to continue to control the numbers of CARICOM nationals through work-permit requirements. Prime Minister Spencer said that Antigua and Prime Minister Baldwin Spencer (left) conferring with the Barbuda has always been a leader in facilitating regional Minister responsible for Barbuda Affairs, Trevor Walker MP integration with 34% of the workforce coming from other Caribbean countries. He remarked, “We agree with the core principles of the CSME and will comply with its obligations. Antigua and Barbuda is on-target to implement the free movement of skills legislation by December 2005 and will allow free movement of persons within the special categories.” In 1991, there were 7,796 CARICOM nationals living in Antigua and Barbuda. That number grew to 13, 695 by 2001, representing a 75% increase. Sections of the CARICOM Secretariat have stated that the derogation which allows Antigua and Barbuda to issue work permits will expire in December of 2005 at the beginning of the full implementation of the CSME. Prime Minister Spencer said that such action would defeat the very purpose for which it was originally granted keeping in mind that Antigua and Barbuda has already integrated the labour market of the region with 34% of the country’s work force comprising CARICOM nationals. -

Antigua and Barbuda Page 1 of 5

Antigua and Barbuda Page 1 of 5 Antigua and Barbuda Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 28, 2005 Antigua and Barbuda is a multiparty, parliamentary democracy governed by a prime minister, a cabinet, and a bicameral legislative assembly. A governor general, appointed by the British monarch, is the titular head of state, with largely ceremonial powers. In March parliamentary elections, which observers described as generally free and fair, the United Progressive Party (UPP) defeated Prime Minster Lester Bird's Antigua Labour Party (ALP), which had controlled the Government and Parliament continuously since 1976. Since taking office, Prime Minister Baldwin Spencer has passed important reform legislation improving government accountability and transparency. The judiciary is independent. Security forces consist of a police force and the small Antigua and Barbuda Defense Force. The security forces are responsible for law enforcement, and civilian authorities maintained effective control of them. Some members of the security forces committed human rights abuses. The country had a mixed economy with a strong private sector. The population was approximately 76,000. Tourism and financial services were the most important source of foreign exchange earnings. The Government was the largest employer, with approximately 13,000 workers. The government's large debt was a serious problem. Real economic growth was projected to be 4 percent for the year. The Labor Commission estimated that the unemployment rate was 11 to 13 percent at year's end. The Government generally respected the human rights of its citizens; however, problems remained in a few areas.