Transgranular Fractures in the Damage Zone of the Punchbowl Fault

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multivariate Discriminant Function Analysis of Camelid Astragali

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org A method for improved identification of postcrania from mammalian fossil assemblages: multivariate discriminant function analysis of camelid astragali Edward Byrd Davis and Brianna K. McHorse ABSTRACT Character-rich craniodental specimens are often the best material for identifying mammalian fossils to the genus or species level, but what can be done with the many assemblages that consist primarily of dissociated postcrania? In localities lacking typi- cally diagnostic remains, accurate identification of postcranial material can improve measures of mammalian diversity for wider-scale studies. Astragali, in particular, are often well-preserved and have been shown to have diagnostic utility in artiodactyls. The Thousand Creek fauna of Nevada (~8 Ma) represents one such assemblage rich in postcranial material but with unknown diversity of many taxa, including camelids. We use discriminant function analysis (DFA) of eight linear measurements on the astragali of contemporaneous camelids with known taxonomic affinity to produce a training set that can then be used to assign taxa to the Thousand Creek camelid material. The dis- criminant function identifies, at minimum, four classes of camels: “Hemiauchenia”, Alforjas, Procamelus, and ?Megatylopus. Adding more specimens to the training set may improve certainty and accuracy for future work, including identification of camelids in other faunas of similar age. For best statistical practice and ease of future use, we recommend using DFA rather than qualitative analyses of biplots to separate and diag- nose taxa. Edward Byrd Davis. University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History and Department of Geological Sciences, 1680 East 15th Avenue, Eugene, Oregon 97403. [email protected] Brianna K. -

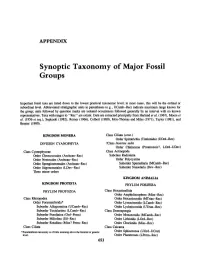

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Mojave Miocene Robert E

Mojave Miocene Robert E. Reynolds, editor California State University Desert Studies Center 2015 Desert Symposium April 2015 Front cover: Rainbow Basin syncline, with rendering of saber cat by Katura Reynolds. Back cover: Cajon Pass Title page: Jedediah Smith’s party crossing the burning Mojave Desert during the 1826 trek to California by Frederic Remington Past volumes in the Desert Symposium series may be accessed at <http://nsm.fullerton.edu/dsc/desert-studies-center-additional-information> 2 2015 desert symposium Table of contents Mojave Miocene: the field trip 7 Robert E. Reynolds and David M. Miller Miocene mammal diversity of the Mojave region in the context of Great Basin mammal history 34 Catherine Badgley, Tara M. Smiley, Katherine Loughney Regional and local correlations of feldspar geochemistry of the Peach Spring Tuff, Alvord Mountain, California 44 David C. Buesch Phytoliths of the Barstow Formation through the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum: preliminary findings 51 Katharine M. Loughney and Selena Y. Smith A fresh look at the Pickhandle Formation: Pyroclastic flows and fossiliferous lacustrine sediments 59 Jennifer Garrison and Robert E. Reynolds Biochronology of Brachycrus (Artiodactyla, Oreodontidae) and downward relocation of the Hemingfordian– Barstovian North American Land Mammal Age boundary in the respective type areas 63 E. Bruce Lander Mediochoerus (Mammalia, Artiodactyla, Oreodontidae, Ticholeptinae) from the Barstow and Hector Formations of the central Mojave Desert Province, southern California, and the Runningwater and Olcott Formations of the northern Nebraska Panhandle—Implications of changes in average adult body size through time and faunal provincialism 83 E. Bruce Lander Review of peccaries from the Barstow Formation of California 108 Donald L. -

Signature Redacted for Privacy. Robeqs. Yeats

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Barbara Jean Ellis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geology presented on May 12, 1994, Title: Changing Tectonic Regimes in the Southern Salinian Block: Extension, Strike-Slip Faulting. Compression and Rotation in the Cuyama Valley, Ca1ifornia ,.Signature redacted forprivacy. Abstract approved: RobeqS.Yeats During the Cenozoic, tectonics in the Cuyama basin of the southeastern Salinian block changed from extension to strike-slip faulting to compression and rotation. During the Oligocene-early Miocene, the Cuyama basin was adjacent to the southern Mojave region and part of that extensional tectonic regime. Many present-day reverse faults have an extensional history. At -P23 Ma, strike-slip faulting began, and the Cuyama basin was part of a zone of distributed shear between the North American and Pacific plates. The Russell fault, which is the oldest documented right-lateral fault in the region, began movement at -P23 Ma which continued until 4 Ma. Tracing its 29 km of slip south of the Big Pine fault is problematic.It may connect with the Blue Rock fault below the Cuyama Badlands, and then correlate with the Clemens Well-Fenner-San Francisquito fault segments, another early strand of the San Andreas fault system to the south. An associated left-lateral fault is proposed to underlie the southeast Caliente Range. The Cox normal fault, which was active during deposition of the Saltos Shale member of the Monterey Formation, is another structure associated with the early right-lateral shear. Compressional tectonics have occurred more recently. The Caliente Range is moving south on the Whiterock and Morales thrusts; the Sierra Madre is moving north on the South Cuyama and Ozena faults. -

Cenozoic Rock Units of the Mojave Desert

CENOZOIC ROCK UNITS OF THE MOJAVE DESERT Thomas W. Dibblee, Jr_ 316 East Mission Street Santa Barbara, California 93101 ABSTRACT The deeply eroded surface of the Pre-Cenozoic basement complex of plutonic and metamorphic rocks of the Mojave Desert is overlain in many parts by Cenozoic sedimentary and volcanic rocks. The oldest are elastic sedimentary rocks of Paleocene-Eocene age, known only along the southwestern and northwestern margins of the western Mojave Desert. These are marine deposits mostly southwest of the San Andreas fault zone, and fluviatile sediments northwest of the Garlock fault zone. Within the Mojave Desert volcanic and sedimentary deposits of early middle Ter- tiary (Oligocene to middle Miocene) age are the oldest and most widespread Ter- tiary rocks. They are extensive in the western and central parts, and present locally in the northern and eastern parts. They are composed primarily of pyro- elastic rocks, and volcanic breccias and flows of rhyolitic to basaltic rocks erupted from many vents and fissures within these parts of the desert terrain. Intercalated with these eruptive rocks are clastic sedimentary rocks composed of agglomerates, fanglomerates and local minor amounts of finer sediments. The age of this assemblage may range from Oligocene to middle Miocene. At one place, a radioactive age (K-A) of 23.5 m.y.b.p. was obtained from rhyolite. All these deposits acumulated on an eroded basement platform in parts of the Mojave Desert region that evolved into depositional basins. The most extensive are in the western and central parts which are designated as the western and central Mojave Desert basins, respectively. -

Sell-0618 , Mohave Project – AZ-CA, Applied Geologic Studies

CONTACT INFORMATION Mining Records Curator Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., Suite 100 Tucson, Arizona 85701 520-770-3500 http://www.azgs.az.gov [email protected] The following file is part of the James Doyle Sell Mining Collection ACCESS STATEMENT These digitized collections are accessible for purposes of education and research. We have indicated what we know about copyright and rights of privacy, publicity, or trademark. Due to the nature of archival collections, we are not always able to identify this information. We are eager to hear from any rights owners, so that we may obtain accurate information. Upon request, we will remove material from public view while we address a rights issue. CONSTRAINTS STATEMENT The Arizona Geological Survey does not claim to control all rights for all materials in its collection. These rights include, but are not limited to: copyright, privacy rights, and cultural protection rights. The User hereby assumes all responsibility for obtaining any rights to use the material in excess of “fair use.” The Survey makes no intellectual property claims to the products created by individual authors in the manuscript collections, except when the author deeded those rights to the Survey or when those authors were employed by the State of Arizona and created intellectual products as a function of their official duties. The Survey does maintain property rights to the physical and digital representations of the works. QUALITY STATEMENT The Arizona Geological Survey is not responsible for the accuracy of the records, information, or opinions that may be contained in the files. The Survey collects, catalogs, and archives data on mineral properties regardless of its views of the veracity or accuracy of those data. -

Perissodactyla, Mammalia) from the Late Miocene of China

Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia (Research in Paleontology and Stratigraphy) vol. 124(1): 1-22. March 2018 SIVALHIPPUS PTYCHODUS AND SIVALHIPPUS PLATYODUS (PERISSODACTYLA, MAMMALIA) FROM THE LATE MIOCENE OF CHINA BOYANG SUN1,2,4, XIAOXIAO ZHANG1,2,3, YAN LIU1 & RAYMOND L. BERNOR⁴ 1Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044. 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100039. 3Tianjin Natural History Museum, Tianjin 300201. 4Corresponding Author. College of Medicine, Department of Anatomy, Laboratory of Evolutionary Biology, Howard University, Washington D.C. 20059. E-mail: [email protected]. To cite this article: Sun B., Zhang X., Liu Y. & Bernor R.L. (2018) - Sivalhippus ptychodus and Sivalhippus platyodus (Perissodactyla, Mammalia) from the Late Miocene of China. Riv. It. Paleontol. Strat., 124(1): 1-22. Keywords: Sivalhippus ptychodus; Sivalhippus platyodus; late Miocene; Evolution; Biogeography. Abstract. Herein, the authors report on skulls, mandibles and postcranial specimens of two species of Chinese Sivalhippus, S. ptychodus and S. platyodus. We frame our description and analyses within the context of newly described characters of the cheek teeth of Hippotherium from the Pannonian C of the Vienna Basin, the oldest and most primitive Old World hipparions. Our report includes original skull, mandibular and limited postcranial ma- terial of Sivalhippus ptychodus and skulls and dentitions of Sivalhippus platyodus from the Paleontological Museum of Uppsala (PMU, Uppsala, Sweden), the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH, New York, USA) and the Licent Collection in Tianjin Natural History Museum (Tianjin, China). The skull, maxillary and mandibular material we attribute to Sivalhippus ptychodus and Sivalhippus platyodus exhibit some primitive features for Old World hipparions and synapamorphies of the face and dentition that unite it with the Sivalhippus clade. -

SVP Comments on 21 U.S. National

Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 9650 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20814- 3998 Phone: (301) 634-7814 Fax: (301) 634-7455 Email: [email protected] Web: www.vertpaleo.org FEIN: 06-0906643 July 9, 2017 Subject: Comments from the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology about the scientific importance of paleontological resources at the 21 U.S. National Monuments established since 1996 (Docket ID: DOI-2017-0002). Executive Summary In this document, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology reviews the paleontological resources currently known from the U.S. National Monuments established since 1996 and explains why altering or revoking their boundaries would be disastrous for the science of paleontology. In these comments, we present: i. our views on the role of public lands in the science of paleontology (p. 2); ii. information on the benefit of paleontological science and education at these monuments to the general public (p. 4); iii. comments on why mining operations are incompatible with discovery and scientific study of paleontological resources (p. 4); iv. specific details about the paleontological resources at each of the continental monuments under review (p 6); v. a copy of the comments we submitted on May 25, 2017, about Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments (tracking number 1k1-8wld-cxoj) (Appendix 1, p. 17); vi. representative scientific publications on paleontological resources at each of the moments (Appendix 2, p. 25) We find that all 21 non-marine monuments protect scientifically important vertebrate fossils or rocks with a high potential for yielding them, and are therefore are appropriately designated under the Antiquities Act of 1906 (note: ‘fossils’ must not to be confused with ‘fossil fuels’). -

2004 Breaking Up

Breaking Up Breaking Up the 2004 Desert Symposium Field Trip Robert E. Reynolds, Editor LSA Associates, Inc. with Abstracts from the 2004 Desert Symposium California State University, Desert Studies Consortium Department of Biological Science California State University, Fullerton Fullerton, California 92384 in association with LSA Associates, Inc. 1650 Spruce Street, Suite 500 Riverside, California 92507 April 2004 1 Desert Symposium 2004 Table of Contents Breaking Up! The Desert Symposium 2004 Field Trip Road Guide Robert E. Reynolds and Miles Kenney ................................................................................................................... 3 Latest Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) fossil assemblage from the Silver Lake Climbing Dune site, northeastern Mojave Desert, California Robert E. Reynolds ............................................................................................................................................. 33 Harper Dry Lake Marsh: past, present, and future Brian Croft and Casey Burns ............................................................................................................................... 39 Mojave River history from an upstream perspective Norman Meek ....................................................................................................................................................41 Non-brittle fault deformation in trench exposure at the Helendale fault Kevin A. Bryan ...................................................................................................................................................51 -

Gravity Study of the San Gabriel Mountains, By

Gravity Study of the San Gabriel Mountains, By Laurence A. WoOd Suimitted in Patial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Science LINDGREN at the MASSACHUIETTS INSTITUTE OF TECIOLOGY June, 1968 Signature of Author . ... Certified by .. The si Supe-rvisor Accepted by ......... Chairman, Departmental Comittee on Thc3es Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.5668 Fax: 617.253.1690 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Due to the poor quality of the original document, there is some spotting or background shading in this document. -2- Abstract A gravity study of the San Gabriel Mountains was made. A map of Bouguer anomalies in the area was completed and a profile across the mountains was taken. Calculations of the crustal thickness beneath the Los Angeles basin, the San Gabriel Mountains, and the Eajave tesert were made using the sin x/x method and a method described by Bott. These calculations indicate that there is a crustal thinning under the San Gabriel Mountains to 27 km. Values of 35 and 38 km were obtained for the Los Angeles basin and the IMojave Desert respectively. These results correspond quite closely to seismic determinations of the crustal thickness in this area. -

Geology on the San Bernardino National Forest

Geologic setting, San Bernardino National Forest Unpublished manuscript J.C. Matti and D.M. Morton, U.S. Geological Survey 02/09/2000 GEOLOGY OF THE SAN BERNARDINO NATIONAL FOREST The San Bernardino National Forest (SBNF) includes parts of, two major geologic-geomorphic provinces of western North America, the Transverse Ranges and Peninsular Ranges provinces. The San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains are part of the eastern Transverse Ranges and the San Jacinto and Santa Rosa Mountains, Thomas Mountain, and Coahuila Mountain are part of the northern Peninsular Ranges. The geology of the two provinces is vastly different one from the other. The Transverse Ranges province boundary south of the San Gabriel Mountains is the Cucamonga fault zone, a major compressional fault zone at the base of the mountains. East of the San Gabriel Mountains the province boundary is right-laterally offset 15-20 km by the San Jacinto fault and is located in the structurally complex San Gorgonio Pass area. Due to fundamental differences in all but the youngest geology, the pre-Quaternary geology of the San Bernardino National Forest is discussed in terms of three rock assemblages, the San Gabriel Mountains assemblage, the San Bernardino Mountains assemblage, and the Peninsular Ranges assemblage. Although within the same geologic-geomorphic province all but the youngest geology of the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains is markedly different. Major lateral displacement on the San Andreas fault has juxtaposed the different rock assemblages of the two ranges. The San Bernardino Mountains rock assemblage underlies the area of the San Gabriel Mountains north of the San Andreas fault in addition to the physiographic San Bernardino Mountains. -

Report Template

5.9 Paleontological Resources 5.9 Paleontological Resources This section evaluates the potential impacts on paleontological resources of the PHPP. The assessment is based a comprehensive literature review, museum records search and fieldwork at the plant site, as well as along the Project’s linear facilities. The evaluation summarizes applicable LORS, discusses the paleontological sensitivity of the Project area and vicinity, evaluates potential Project-related impacts on the paleontological resources identified, and provides recommendations for mitigating potential impacts. This assessment was conducted in accordance with the professional standards of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP). The assessment was performed by qualified paleontological professionals. Additional details of the assessment, including personnel qualifications, are provided in Appendix J. Paleontology is a multidisciplinary science that combines elements of geology, biology, chemistry, and physics in an effort to understand the history of life on earth. Paleontological resources, or fossils, are the remains, imprints, or traces of once-living organisms preserved in rocks and sediments. These include mineralized, partially mineralized, or unmineralized bones and teeth, soft tissues, shells, wood, leaf impressions, footprints, burrows, and microscopic remains. The fossil record is the only evidence that life on earth has existed for more than 3.6 billion years. Fossils are considered nonrenewable resources because the organisms they represent no longer exist. Once destroyed, a fossil can never be replaced. 5.9.1 LORS Compliance Fossils are classified as nonrenewable scientific resources and are protected by various laws, ordinances, regulations, and standards (LORS) across the country. These LORS are summarized in Table 5.9-1, and the following paragraphs.