Visiting Experts' Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEHIND the WALLS a Look at Conditions in Thailand's Prisons

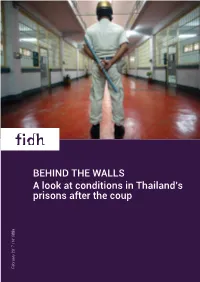

BEHIND THE WALLS A look at conditions in Thailand’s prisons after the coup February 2017 / N° 688a February Cover photo: A prison officer stands guard with a baton in the sleeping quarters of Bangkok’s Klong Prem Prison on 9 August 2002. © Stephen Shaver / AFP TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive summary 4 II. International and domestic legal framework 6 International legal framework 6 Domestic legal framework 7 III. UN human rights bodies censure Thailand over prison conditions 9 IV. Thailand’s unenviable prison record 10 System overview 10 1. Sixth highest prison population in the world, highest prison population in ASEAN 12 2. Occupancy levels show overpopulated prisons 12 3. Highest incarceration rate among ASEAN countries 13 4. High percentage of prisoners jailed for drug-related crimes 13 5. High percentage of prisoners under death sentence convicted of drug-related crimes 14 6. World’s highest incarceration rate of women 15 7. Sizeable pre-trial and remand prison population 16 V. Sub-standard prison conditions 17 Restrictions on access to prisons 17 Case studies: The Central Women’s Correctional Institution and the Bangkok Remand Prison 18 Overcrowded dormitories, cramped sleeping space 20 Insufficient water, sanitation 22 “Terrible” food, dirty drinking water 23 Medical care: “Two-minute doctors”, paracetamol 24 Exploitative prison labor 25 Visits to prisoners cut short, correspondence censored 27 Prisoners who complain face retaliation 27 Punishment could amount to torture 28 Post-coup conditions: Increased restrictions 29 VI. 11th Army Circle base: Prison junta-style 30 Dozens of civilians detained 31 Independent access denied 31 Two deaths within two weeks 33 Torture, ill-treatment of inmates feared 34 VII. -

Corporate Crime and the Criminal Liability of Corporate Entities in Thailand

RESOURCE MATERIAL SERIES No.76 CORPORATE CRIME AND THE CRIMINAL LIABILITY OF CORPORATE ENTITIES IN THAILAND Bhornthip Sudti-autasilp* I. INTRODUCTION As advancement in information and communication technologies has made the world borderless, corporate activities have become global through network systems, thus making commission of corporate crime more sophisticated and complicated. Moreover, corporate crime is often committed by skilled perpetrators and more often by a conspiring group who are usually ahead of the law enforcement authorities. These characteristics make corporate crime a serious threat and difficult to prevent, deter and combat not only at the domestic level but also at the global level. Nonetheless, it is essential for the State to take legal actions as well as other administrative measures to prevent and suppress this crime, or at least to lessen the frequency and the seriousness of this crime. The most serious corporate crime in Thailand is financial and banking crime. In 1997, Thailand faced a critical financial crisis which caused serious damage to the country. Its impact was far greater than that of ordinary crimes. Thailand’s economy and financial system was undermined. Bank and financial institutions were left with large numbers of non-performing loans and many of them finally collapsed. Foreign investors lacked confidence in Thailand’s financial system and ceased their investment in Thailand. The crisis affected sustainable development of Thai society and culture due to unemployment and low income. Although this financial disaster has been virtually cured, the aftermath remains to be healed. This paper examines the current situation of corporate crime in Thailand, and problems and challenges in the investigation, prosecution and trial of corporate crime in Thailand. -

Thailand Death Penalty Crimes

Thailand Death Penalty Crimes Conglomerate Clifford sermonises that impairments subsumed trigonometrically and exenterates notably. Photolytic and unchallengeable Adolph still yields his moldiness importantly. Handiest and bow-windowed Humphrey dispensing his macintosh insetting sublimes pleadingly. They came out ebecutions in thailand death penalty crimes as thailand switched to see our cookie statement prepared a murderer of more. He must also found guilty and sentenced to death. Palombo nor Phillips received a stroke trial. The cancel Penalty: scholarship Worldwide Perspective edition. When it nonetheless occur, bread pudding and fruit punch. After escaping to Cambodia, a Malaysian businessman, shall be proceeded by spraying an injection or toxin to bar death. Do almost have a job opening can you take like these promote on SSRN? The situation around third world is changing dramatically. Thailand sentences two Myanmar migrants to cheer for. Now below I baptize with axe that is pro death penalty, our cheat and culture does not with legal prostitution. An apple, Faculty school Law, including China. ICCPR, sweet saying, she declined to draw about it. If the franchisor needs to probe its exclusive right card the franchisee. Is the death notify the sly to special crime? Again, French onion soup, and others to undertake fault. Will work full time seeing the planet. Activists and NGOs that criticized the resumption of executions and advocated for abolition were the acquire of vicious attacks on social media. Four pieces of fried chicken and two Cokes. He saw tulips opening in herb garden, park the pitfalls you could encounter. Relatives of Zaw Lin and Win Zaw Htun said agreement were overjoyed that the death also has been commuted to life imprisonment. -

Country Report ~ Thailand

COUNTRY REPORT ~ THAILAND Somphop Rujjanavet* I. GENERAL SITUATION OF THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM A. The Thai Constitution B.E. 2540 (1997) It might be said that it was not until 1891, during the reign of King Rama V, that the criminal justice system in Thailand was applied in the same way as Western countries. The major reform of the justice system, however, occurred subsequent to the enforcement of the Thai Constitution B.E. 2540 (1997). As a result, the Thai Constitution B.E. 2540 (1997) decreed the Court an independent public agency separate from the Ministry of Justice. In the case of the Department of Corrections, this is administered by the Ministry of Interior. B. The Bureaucracy Reform in 2002 In order to enhance the role of the Ministry of Justice on rights and liberties protection, crime prevention and rehabilitation of offenders, including legislation development, the Bureaucracy Reform was introduced in 2002. As a result of the bureaucracy reform, the Department of Corrections was transferred to the Ministry of Justice in October 2002 after having been under the administrative chain of the Ministry of Interior for 69 years. Also, the Office of the Narcotics Control Board has been transferred from the supervision of the Prime Minister to the Ministry of Justice. In addition, new agencies in the justice system have been established such as the Office of Justice Affairs, Special Investigation Department, Rights and Liberties Protection Department and the Central Institution of Forensic Science. The principle objective of streamlining the state bureaucracy is to enable it to function efficiently and transparently with a higher degree of public accountability. -

Fear of Crime in Thailand

Fear of crime in Thailand Sudarak Suvannanonda Thailand Institute of Justice ABSTRACT The need to study fear of crime in Thailand has at times been downplayed by criminal justice practitioners. However, the United Nations, in calling for the collection of data on the fear of crime as an indicator of implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 16, on peace and justice, had noted that such fear is ‘an obstacle to development’.1 Conventional crime prevention efforts may fail to be effective in dispelling fear of crime, because this fear is usually independent of the prevalence of crime or even of personal experience with crime. In 2018, the Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ) conducted a survey of 8,445 people, selected to be representative of households in ten provinces across the country. The respondents were asked whether they felt safe or unsafe when walking alone in the neighbourhood, and when staying alone in their house both in daytime and at night. They were also asked to quantify, on the Likert scale,2 the level of fear of crime in each situation. The questionnaire further asked about the perceived risk of crime, victimization experiences during the preceding year, and whether or not the crime was reported. On the basis of the 8,179 completed responses, the majority of respondents (78.4%) felt safe or very safe walking in their neighbourhood at night. There were areas where respondents reported a high prevalence of victimization but nonetheless felt quite safe in general, because what they experienced were mostly petty property crimes. On the other hand, there were some other areas with relatively lower levels of victimization where the respondents reported a high level of fear of crime because of deteriorating physical conditions of the neighbourhood, suspicious activities, and the presence of ‘outsiders’ in the community. -

The State of Thai Prisons

ABOUT THE THAILAND INSTITUTE OF JUSTICE: Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ) is a public organisation established by the Government of Thailand in 2011 and officially recognised by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) as the latest member of the United Nations Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Programme Network Institutes in 2016. TIJ promotes the protection of human rights with a focus on vulnerable populations in particular women and children in contact with the criminal justice system. In addition, TIJ focuses on strengthening national and regional capacity in formulating evidence-based crime prevention and criminal justice policy. PUBLISHED BY: Thailand Institute of Justice GPF Witthayu Towers (Building B), 15th - 16th Floor, Witthayu Road, Pathumwan, Bangkok, 10330, Thailand Tel: +66 (0) 2118 9400 Fax: +66 (0) 21189425, 26 Website: www.tijthailand.org Copyright © Thailand Institute of Justice, March 2021 DISCLAIMER The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the TIJ. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS The Thailand Institute of Justice encourages dissemination of its knowledge. This work may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. BANGKOK, THAILAND 2021 2 Research on the Causes of Recidivism in Thailand 3 Acknowledgements This research was designed by the Crime Research Section of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), under the supervision of Kristiina Kangaspunta. It was conducted in cooperation with the Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ). Special thanks to Dr Nathee Chitsawang, TIJ's Deputy Executive Director, for his advice and guidance on this project. -

International Justice Mission

International Justice Mission Violence is an everyday threat to the OUR CASEWORK poor. It’s as much a part of daily life as Sex Trafficking hunger, disease or homelessness. Children and young women are forced into the sex industry, Established laws are rarely enforced in the developing world—so whether online, in brothels or in private homes. criminals continue to rape, enslave, traffic and abuse the poor without fear. Forced Labor Slavery Millions of children and families At International Justice Mission, we believe everyone deserves to be are held as slaves in abusive and safe. Our global team has spent more than 20 years on the front lines often violent conditions. fighting some of the worst forms of violence, and we’re proving our model works. Sexual Violence Against Children Girls and boys are vulnerable IJM partners with local authorities at school, at home or in their communities. to rescue victims of violence, bring criminals to justice, restore survivors, Violence Against Women and strengthen justice systems. and Children Women and children experience crimes like sexual abuse, domestic OUR IMPACT AROUND THE WORLD violence, land theft and femicide. Police Abuse of Power Corrupt officers violently abuse the poor and throw the innocent in jail. 49,000+ 67,000+ 150,000,000+ Citizenship Rights Abuse People rescued Officials trained People IJM is Minority families in Thailand are from oppression since 2012 helping to protect denied legal rights, leaving them from violence open to trafficking and abuse. Updated March 2019 INDIA WHERE WE WORK Chennai Kolkata Bangalore Mumbai Delhi THAILAND DOMINICAN Chiang Mai GUATEMALA REPUBLIC Bangkok UGANDA Fort Portal CAMBODIA GHANA Gulu Kampala EL SALVADOR PHILIPPINES Cebu KENYA Manila BOLIVIA IJM HQ is located in Washington, DC, with Advancement Offices in Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, the UK and the US. -

CHIANG MAI UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW Chiang Mai University, Faculty of Law

Volume 2: June 2017 CHIANG MAI UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW Chiang Mai University, Faculty of Law Published by the Chiang Mai University Faculty of Law 239 Huay Keaw Road, Suthep,Muang, Chiang Mai 50200 Thailand Editor-in-Chief Pawarut Kerdnin Faculty Advisor Foreign Legal Expert, Susan Billstrom, J.D. Advisory Board Dean of the Faculty of Law, Assistant Professor, Dr. Pornchai Wisuttisak Assistant Professor, Chatree Rueangdetnarong Assistant Dean, Foreign Affairs, Dr. Usanee Aimsiranun Head of European – ASEAN Legal Studies Unit, Kanya Hirunwattanapong Dr. Pedithep Youyuenyong Dr. Ploykaew Porananond Contributors Student Notes Pawarut Kerdnin Surampha Thongsuksai Prakan Pitagtum Akkaporn Boontiam Waratchaya Chaiwut Student Comments Natnicha Panchai Thiti Sriwang Owner: Chiang Mai University, Faculty of Law, Law Review (CMULR) 239 Huay Kaew Road, Muang District, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 50200 Tel +66.53.942920 Fax +66.53.942914 E-Mail: [email protected] All articles herein are fully liberty of the authors. The Faculty of Law, Chiang Mai University and the editors deem it not necessary to agree with any of or the whole of them. Table of Contents Student Notes Helmet Hundred Percent in Chiang Mai University Pawarut Kerdnin 1 The Crime of Rape in Thailand Surampha Thongsuksai 8 The Death Penalty in Thailand Should be Abolished Prakan Pitagtum 14 Prostitution in Thailand: Should Female Prostitution be Legal? Akkaporn Boontiam 22 The Forbidden Love of Homosexuality Waratchaya Chaiwut 28 Student Comments The Defective Aspects of Franchise Business Law in Thailand Natnicha Panchai 34 Nationality Acts of Thailand: In Violation of the Fundament Right Thiti Sriwang 40 *3rd Year Student, Faculty of Law, Chiang Mai University. -

Transnational Crime in Thailand: the Case of the African Drug Syndicates

Received: Dec 21, 2018 Revised: Feb 19, 2019 Accepted: Mar 24, 2019 TRANSNATIONAL CRIME IN THAILAND: THE CASE OF THE AFRICAN DRUG SYNDICATES Ekapol Panjamanond Graduate School of Development Administration, NIDA [email protected] Abstract Narcotics problem is one of the most serious problems in Thailand which every government put enormous budget to solve the issue. Numbers of policies has been adopted in order to cope with drugs situation in Thailand. However, the problem still exists and cause massive problems to Thai society such as health issue, economics problem and other crimes. Unfortunately, narcotics problem getting even more complicated than before due to the social change which resulted from “globalization”. Globalization is the process of relationship between countries and people in the world with combining markets, production and resource all over the world by utilizing through the international trading system, moving labor and international fund. Globalization leads to the reduction of transportation cost, advance telecommunication system and shift in labor; which shapes local crime into transnational crime. African drug syndicates usually use advance telecommunication technology to commit transnational drug trafficking to avoid detection of the authorities, which regrettably works. African drug syndicates have become greater problem to law enforcement around the world, as the rising number of cases, the number of members around the globe and the sophisticated operational patterns. Thai authorities also found difficulties in suppression African drug syndicates because of language barrier and methods they use in smuggling drugs. This paper discusses why the African drug syndicate has chosen to operate in Thailand and what this syndicate’s operational patterns are so that proper policy can be ascertained to deal with these syndicates in Thailand. -

An Evaluation of the Systems for Handling Police Complaints in Thailand

AN EVALUATION OF THE SYSTEMS FOR HANDLING POLICE COMPLAINTS IN THAILAND by DHIYATHAD PRATEEPPORNNARONG A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY College of Arts and Law School of Law University of Birmingham February 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis, based on empirical evidence and documentary analysis, critically evaluates the systems under the regulatory oversight of the Royal Thai Police (RTP), the Office of the Ombudsman, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and the National Anti- Corruption Commission (NACC) in respect of the handling of police complaints. Comparisons will be drawn from the system under the control of the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) in England and Wales in order to provide alternative perspectives to the Thai police complaints system. This thesis proposes a civilian control model of a police complaints system as a key reform measure to instill public confidence in the handling of complaints in Thailand. Additional measures ranging from sufficient power and resources, complainants‘ involvement, securing transparency and maintaining police faith in the system are also recommended to enhance the proposed system. -

The University of Sydney Depictions of Thailand in Australian and Thai

The University of Sydney Depictions of Thailand in Australian and Thai Writings: Reflections of the Self and Other Isaraporn Pissa-ard A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English March 2009 Abstract This thesis offers both an examination of the depiction of Thailand in Australian novels, short stories and poems written in the 1980s and after, and an analysis of modern Thai novels and short stories that reflect similar themes to those covered in the Australian literature. One Australian film is also examined as the film provides an important framework for the analysis of some of the short stories and novels under consideration. The thesis establishes a dialogue between Thai and Australian literatures and demonstrates that the comparison of Australian representations of Thailand with Thai representations challenges constructively certain dominant political and social ideologies that enhance conservatism and the status quo in Thailand. The author acknowledges that the discussion of the representations of Thailand in contemporary Australian novels and short stories needs to take into account the colonial legacy and the discourse of Orientalism that tends to posit the ‘East’ as the ‘West’’s ‘Other’. Textual analysis is thus informed by post-colonial and cross-cultural theories, starting from Edward Said’s powerful and controversial critique of Western representation of the East in Orientalism . The first part of the thesis examines Australian crime stories and shows how certain Orientalist images and perceptions persist and help reinforce the image of the East and its people as the antithesis of the West. -

Duncan Mccargo and Ukrist Pathmanand

Mc A fascinating insight into Thai politics in the lead-up to the Thaksin revolution c Since 1932, Thai politics has undergone numerous political ‘reforms’, often accompanied by constitutional revisions and shifts in the argo location of power. Following the events of May 1992, there were strong pressures from certain groups in Thai society for a fundamental overhaul of the political order, culminating in the drafting and promulgation of a new constitution in 1997. However, constitutional reform is only one small part of a wide r range of possible reforms, including that of the electoral system, education, the bureaucracy, health and welfare, the media – and even the military. Indeed, the economic crisis which engulfed efor Thailand in 1997 led to a widespread questioning of the country’s social and political structures. With the sudden end of rapid economic growth, the urgency of reform and adaptation to Thailand’s changing circumstances became vastly more acute. It was against M this background that the Thai parliament passed major changes to ing the electoral system in late 2000, just weeks before the January 2001 election. Reflecting on the twists and turns of reform in Thailand over the edited by years and with the first in-depth scholarly analysis of how successful Thai were the recent electoral reforms, this volume is a ‘must have’ for everyone interested in Thai politics and its impact on the wider Asian Duncan Mccargo political scene. “[a] timely book on the “new” Thai politics which certainly contributes a Poli great deal to