Inferring the Evolutionary History of Divergence Despite Gene Flow in A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

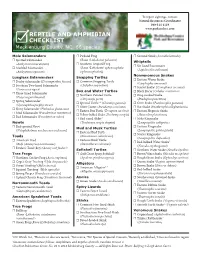

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

Scincella Lateralis)

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 7(2): 109–114. Submitted: 30 January 2012; Accepted: 30 June 2012; Published: 10 September 2012. SEXUAL DIMORPHISM IN HEAD SIZE IN THE LITTLE BROWN SKINK (SCINCELLA LATERALIS) 1 BRIAN M. BECKER AND MARK A. PAULISSEN Department of Natural Sciences, Northeastern State University, Tahlequah, Oklahoma 74464, USA 1Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Many species of skinks show pronounced sexual dimorphism in that males have larger heads relative to their size than females. This can occur in species in which males have greater body length and show different coloration than females, such as several species of the North American genus Plestiodon, but can also occur in species in which males and females have the same body length, or species in which females are larger than males. Another North American skink species, Scincella lateralis, does not exhibit obvious sexual dimorphism. However, behavioral data suggest sexual differences in head size might be expected because male S. lateralis are more aggressive than females and because these aggressive interactions often involve biting. In this study, we measured snout-to-vent length and head dimensions of 31 male and 35 female S. lateralis from northeastern Oklahoma. Females were slightly larger than males, but males had longer, wider, and deeper heads for their size than females. Sexual dimorphism in head size may be the result of sexual selection favoring larger heads in males in male-male contests. However, male S. lateralis are also aggressive to females and larger male head size may give males an advantage in contests with females whose body sizes are equal to or larger than theirs. -

First Record of Brown Forest Skink, Scincella Cherriei (Cope, 1893) (Squamata:Scincidae) in El Salvador

Herpetology Notes, volume 13: 715-716 (2020) (published online on 25 August 2020) First record of brown forest skink, Scincella cherriei (Cope, 1893) (Squamata:Scincidae) in El Salvador Antonio E. Valdenegro-Brito1,2, Néstor Herrera-Serrano3, and Uri O. García-Vázquez1,* The Scincella Mittleman, 1950 genus is composed by 2015; Valdenegro-Brito et al., 2016; McCranie, 2018). 36 species, 26 restricted to eastern Asia and 10 species Here, we report the first record of S. cherrie from El are known in the New World in North America, and Salvador. The digital photographs of specimens were Mesoamerica (Myers and Donelly, 1991; Nguyen et al., submitted to the Colección digital de vertebrados de 2019). For El Salvador in Central America, Scincella la Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza, UNAM assata (Cope, 1864) represents the only species of (MZFZ-IMG). the genus know for the country (Köhler et al., 2006). While conducting fieldwork in El Salvador, on 10 Scincella cherriei (Cope, 1893) is characterised November 2019, we observed two male juvenile by possessing 30 to 36 rows of scales around the individuals (MZFZ-IMG254-56 and MZFZ-IMG257- midbody, 58-72 dorsal scales, thick and moderately 260; Fig. 1) of S. cherriei in a coffee plantation within long pentadactyl limbs, average snout-vent length of an oak pine forest in the locality of San José Sacare, 55 mm; the dorsal colouration is dark brown with a municipality of La Palma, Chalatenango department mottled pattern throughout the body, and a well-defined (14. 27079ºN, 89. 17995ºW; datum WGS84) 1215 lateral dark stripe only in the head and neck, which m a.s.l. -

The Spatial Ecology of the Southern Copperhead in a Fragmented and Non-Fragmented Habitat

Coastal Carolina University CCU Digital Commons Electronic Theses and Dissertations College of Graduate Studies and Research 1-1-2017 The pS atial Ecology of the Southern Copperhead in a Fragmented and Non-Fragmented Habitat Megan Veronica Novak Coastal Carolina University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Novak, Megan Veronica, "The pS atial Ecology of the Southern Copperhead in a Fragmented and Non-Fragmented Habitat" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 38. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/etd/38 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Graduate Studies and Research at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SPATIAL ECOLOGY OF THE SOUTHERN COPPERHEAD IN A FRAGMENTED AND NON-FRAGMENTED HABITAT By Megan Veronica Novak Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Coastal Marine and Wetland Studies in the School of Coastal and Marine Systems Science Coastal Carolina University 2017 ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Scott Parker, Major Professor Dr. Lindsey Bell, Committee Member ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Derek Crane, Committee Member Dr. Louis Keiner, Committee Member ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. Richard Viso, CMWS Director Dr. Michael Roberts, Dean ii The spatial ecology of the southern copperhead in a fragmented and non-fragmented habitat Megan Veronica Novak Coastal Marine and Wetland Studies Program Coastal Carolina University Conway, South Carolina ABSTRACT Habitat fragmentation may alter the spatial ecology of organisms inhabiting the fragmented landscape by limiting the area of habitat available and altering microhabitat features. -

Protozoan, Helminth, and Arthropod Parasites of the Sported Chorus Frog, Pseudacris Clarkii (Anura: Hylidae), from North-Central Texas

J. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 58(1), 1991, pp. 51-56 Protozoan, Helminth, and Arthropod Parasites of the Sported Chorus Frog, Pseudacris clarkii (Anura: Hylidae), from North-central Texas CHRIS T. MCALLISTER Renal-Metabolic Lab (151-G), Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 4500 S. Lancaster Road, Dallas, Texas 75216 ABSTRACT: Thirty-nine juvenile and adult spotted chorus frogs, Pseudacris clarkii, were collected from 3 counties of north-central Texas and examined for parasites. Thirty-three (85%) of the P. clarkii were found to be infected with 1 or more parasites, including Hexamita intestinalis Dujardin, 1841, Tritrichomonas augusta Alexeieff, 1911, Opalina sp. Purkinje and Valentin, 1840, Nyctotherus cordiformis Ehrenberg, 1838, Myxidium serotinum Kudo and Sprague, 1940, Cylindrotaenia americana Jewell, 1916, Cosmocercoides variabilis (Harwood, 1930) Travassos, 1931, and Hannemania sp. Oudemans, 1911. All represent new host records for the respective parasites. In addition, a summary of the 36 species of amphibians and reptiles reported to be hosts of Cylin- drotaenia americana is presented. KEY WORDS: Anura, Cosmocercoides variabilis, Cylindrotaenia americana, Hannemania sp., Hexamita in- testinalis, Hylidae, intensity, Myxidium serotinum, Nyctotherus cordiformis, Opalina sp., prevalence, Pseudacris clarkii, spotted chorus frog, survey, Tritrichomonas augusta. The spotted chorus frog, Pseudacris clarkii ported to the laboratory where they were killed with (Baird, 1854), is a small, secretive, hylid anuran an overdose of Nembutal®. Necropsy and parasite techniques are identical to the methods of McAllister that ranges from north-central Kansas south- (1987) and McAllister and Upton (1987a, b), except ward through central Oklahoma and Texas to that cestodes were stained with Semichon's acetocar- northeastern Tamaulipas, Mexico (Conant, mine and larval chiggers were fixed in situ with 10% 1975). -

A Brief Review of the Guatemalan Lizards of the Genus Anolis

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 91 A Brief Review of the Guatemalan Lizards of the Genus Anolis BY L. C. STUART ANN ARBOR MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN June 6, 1955 LIST OF THE MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS OF THE MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Address inquiries to the Director of the Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan *On sale from the University Press, 311 Maynard St., Ann Arbor, Michigan. Bound in Paper No. 1. Directions for Collecting and Preserving Specimens of Dragonflies for Museum Purposes. By E. B. Williamson. (1916) Pp. 15, 3 figures No. 2. An Annotated List of the Odonata of Indiana. By E. B. Williamson. (1917) Pp. 12, 1 map No. 3. A Collecting Trip to Colombia, South America. By E. B. Williamson. (1918) Pp. 24 (Out of print) No. 4. Contributions to the Botany of Michigan. By C. K. Dodge. (1918) Pp. 14 No. 5. Contributions to the Botany of Michigan, II. By C. K. Dodge. (1918) Pp. 44, 1 map No. 6. A Synopsis of the Classification of the Fresh-water Mollusca of North America, North of Mexico, and a Catalogue of the More Recently Described Species, with Notes. By Bryant Walker. (1918) Pp. 213, 1 plate, 233 figures No. 7. The Anculosae of the Alabama River Drainage. By Calvin Goodrich. (1922) Pp. 57, 3 plates No. 8. The Amphibians and Reptiles of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. By Alexander G. Ruthven. (1922) Pp. 69, 13 plates, 2 figures, 1 map No. 9. Notes on American Species of Triacanthagyna and Gynacantha. -

Further Dismemberment of the Pan-Continental

18 Australasian Journal of Herpetology Australasian Journal of Herpetology 41:18-28. Published 1 August 2019. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) Further dismemberment of the pan-continental Lizard genus Scincella Mittleman, 1950 with the creation of four new genera to accommodate divergent species and the formal descriptions of six new species. LSID urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:816D2F9D-3C4E-46C0-9B97-79F433D67996 RAYMOND T. HOSER 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: snakeman (at) snakeman.com.au Received 11 November 2018, Accepted 11 May 2019, Published 1 August 2019. ABSTRACT The genus Scincella Mittleman, 1950 as currently recognized has been shown in numerous studies to be paraphyletic. Since the creation of the genus, some divergent species have been split off into separate genera (e.g. Kaestlea Eremchenko and Das, 2004 and Asymblepharus Eremchenko and Szczerbak, 1980) or transferred to others. Continuing with this dismemberment of the genus, this paper relies on both morphological and molecular evidence to further refine the genus-level classification of Scincella sensu lato. Four new genera for Asiatic species are formally erected according to the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (Ride et al. 1999) as well as two subgenera within one of the new genera. Six obviously unnamed species are also formally named in this paper, so that their conservation and management can be properly implemented and before any species runs the increased risk of becoming extinct through indifference both by the scientific community and regulatory authorities who depend on them. -

Liolaemus Multimaculatus

VOLUME 14, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2007 ONSERVATION AUANATURAL ISTORY AND USBANDRY OF EPTILES IC G, N H , H R International Reptile Conservation Foundation www.IRCF.org ROBERT POWELL ROBERT St. Vincent Dwarf Gecko (Sphaerodactylus vincenti) FEDERICO KACOLIRIS ARI R. FLAGLE The survival of Sand Dune Lizards (Liolaemus multimaculatus) in Boelen’s Python (Morelia boeleni) was described only 50 years ago, tes- Argentina is threatened by alterations to the habitats for which they tament to its remote distribution nestled deep in the mountains of are uniquely adapted (see article on p. 66). Papua Indonesia (see article on p. 86). LUTZ DIRKSEN ALI REZA Dark Leaf Litter Frogs (Leptobrachium smithii) from Bangladesh have Although any use of Green Anacondas (Eunectes murinus) is prohibited very distinctive red eyes (see travelogue on p. 108). by Venezuelan law, illegal harvests are common (see article on p. 74). CHARLES H. SMITH, U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE GARY S. CASPER Butler’s Garter Snake (Thamnophis butleri) was listed as a Threatened The Golden Toad (Bufo periglenes) of Central America was discovered Species in Wisconsin in 1997. An effort to remove these snakes from in 1966. From April to July 1987, over 1,500 adult toads were seen. the Wisconsin list of threatened wildlife has been thwarted for the Only ten or eleven toads were seen in 1988, and none have been seen moment (see article on p. 94). since 15 May 1989 (see Commentary on p. 122). About the Cover Diminutive geckos (< 1 g) in the genus Sphaerodactylus are widely distributed and represented by over 80 species in the West Indies. -

Amphibians and Reptiles Of

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Amphibians and Reptiles of Aransas National Wildlife Refuge Abundance Common Name Abundance Common Name Abundance C Common; suitable habitat is available, Scientific Name Scientific Name should not be missed during appropriate season. Toads and Frogs Texas Tortoise R Couch’s Spadefoot C Gopherus berlandieri U Uncommon; present in moderate Scaphiopus couchi Guadalupe Spiny Soft-shelled Turtle R numbers (often due to low availability Hurter’s Spadefoot C Trionyx spiniferus guadalupensis of suitable habitat); not seen every Scaphiopus hurteri Loggerhead O visit during season Blanchard’s Cricket Frog U Caretta caretta Acris crepitans blanchardi Atlantic Green Turtle O O Occasional; present, observed only Green Tree Frog C Chelonia mydas mydas a few times per season; also includes Hyla cinerea Atlantic Hawksbill O those species which do not occur year, Squirrel Tree Frog U Eretmochelys imbricata imbricata while in some years may be Hyla squirella Atlantic Ridley(Kemp’s Ridley) O fairly common. Spotted Chorus Frog U Lepidocheyls kempi Pseudacris clarki Leatherback R R Rare; observed only every 1 to 5 Strecker’s Chorus Frog U Dermochelys coriacea years; records for species at Aransas Pseudacris streckeri are sporadic and few. Texas Toad R Lizards Bufo speciosus Mediterranean Gecko C Introduction Gulf Coast Toad C Hemidactylus turcicus turcicus Amphibians have moist, glandular skins, Bufo valliceps valliceps Keeled Earless Lizard R and their toes are devoid of claws. Their Bullfrog C Holbrookia propinqua propinqua young pass through a larval, usually Rana catesbeiana Texas Horned Lizard R aquatic, stage before they metamorphose Southern Leopard Frog C Phrynosoma cornutum into the adult form. -

Cytogenetics of the Skinks (Reptilia, Scincidae) from Thailand; IV: Newly Investigated Karyotypic Features of Lygosoma Quadrupes and Scincella Melanosticta

Caryologia International Journal of Cytology, Cytosystematics and Cytogenetics ISSN: 0008-7114 (Print) 2165-5391 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tcar20 Cytogenetics of the skinks (Reptilia, Scincidae) from Thailand; IV: newly investigated karyotypic features of Lygosoma quadrupes and Scincella melanosticta Isara Patawang, Yodchaiy Chuaynkern, Praween Supanuam, Nuntiya Maneechot, Krit Pinthong & Alongklod Tanomtong To cite this article: Isara Patawang, Yodchaiy Chuaynkern, Praween Supanuam, Nuntiya Maneechot, Krit Pinthong & Alongklod Tanomtong (2017): Cytogenetics of the skinks (Reptilia, Scincidae) from Thailand; IV: newly investigated karyotypic features of Lygosoma quadrupes and Scincella melanosticta, Caryologia, DOI: 10.1080/00087114.2017.1402249 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00087114.2017.1402249 Published online: 18 Dec 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tcar20 Download by: [Chiang Mai University] Date: 18 December 2017, At: 22:17 CARYOLOGIA: INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CYTOLOGY, CYTOSYSTEMATICS AND CYTOGENETICS, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/00087114.2017.1402249 Cytogenetics of the skinks (Reptilia, Scincidae) from Thailand; IV: newly investigated karyotypic features of Lygosoma quadrupes and Scincella melanosticta Isara Patawanga,b, Yodchaiy Chuaynkernc , Praween Supanuamd, Nuntiya Maneechote, Krit Pinthonge and Alongklod -

Field Notes: Scincella Lateralis

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Biology and Chemistry 2005 Field Notes: Scincella lateralis Timothy R. Brophy Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Brophy, Timothy R., "Field Notes: Scincella lateralis" (2005). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 41. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs/41 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology and Chemistry at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CATESBE/ANA 2005, 25(2) The Rockbridge County skink was observed foraging for arthropods for several minutes along the edge of the gravel and dirt berm beside the wooded edge of the road (FS 439). The site had little to no canopy cover Field Notes over the road. The road was composed primarily of an exposed shale and limestone gravel with little ground vegetation. The skink was not Eltmeees fasciallts (Five-lined Skink). Washington, Co., 18517 Hillbilly photographed or vouchered and no measurements were taken. Site Lane, Bristol (UTM: 39.6446, 40.60222). 10 June 2005. David Carrier. elevation was approximately 548 meters. On 10 June 2005, David Carrier submitted to the Virginia Department of At the Montgomery County site, one male was captured and released. No Game and Inland Fisheries two digital photographs of what he believed to measurements were taken and it was not photographed. Sides of the head be Eumeees la/ieeps (Broad-headed skink). -

New Records and an Updated List of Herpetofauna from Cerro Piedra Larga, an Isolated Mountain Massif in Oaxaca, Mexico

Herpetology Notes, volume 10: 651-658 (2017) (published online on 23 November 2017) New records and an updated list of herpetofauna from Cerro Piedra Larga, an isolated mountain massif in Oaxaca, Mexico Rafael Alejandro Calzada-Arciniega1,*, Ernesto Recuero2, 3, Mirna G. García-Castillo1 and Gabriela Parra-Olea1 Abstract. Oaxaca has the highest diversity of amphibians and reptiles of all the states in Mexico. Cerro Piedra Larga is an isolated mountain located in the southeast region of Oaxaca; this massif is covered by mixed temperate and cloud forest and surrounded by drier lowlands. A previous study reported a high diversity of vertebrate fauna on the massif, with 34 species of herpetofauna. During a sampling field trip to Cerro Piedra Larga in September 2014 we found a total of 22 species of amphibians and reptiles, 10 of which represent new records to the area, including six Mexican endemics. Our new records include two salamander species known previously only from their type localities in separate physiographic provinces and the others represent an extension to their geographical known distribution. With the new data we provide herein, Cerro Piedra Larga reaches 42 species of amphibians and reptiles. Keywords: Amphibians, Reptiles, Conservation, Diversity, Distributional records, Plethodontidae, Salamanders, Checklist Introduction position in the transition zone between the neartic and neotropical zones (Casas-Andreu et al., 1996). Although The state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico covers an southern Mexico, and specifically the state of Oaxaca, area of 93000 km2 and supports the highest diversity is one of the better studied areas compared to most of of reptiles (293 species) and amphibians (149 species) the northern parts of the country, the known diversity in the country, with very a high degree of endemism of this region increases every year with new records (93 species, 21%).