Birds in Quarries and Gravel Pits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acoustic Signalling in Eurasian Penduline Tits Remiz Pendulinus Pogany, A.; Van Dijk, R

University of Groningen Acoustic signalling in Eurasian penduline tits remiz pendulinus Pogany, A.; van Dijk, R. E.; Menyhart, O.; Miklosi, A.; DeVoogd, T. J.; Szekely, T. Published in: Acta zoologica academiae scientiarum hungaricae IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2013 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Pogany, A., van Dijk, R. E., Menyhart, O., Miklosi, A., DeVoogd, T. J., & Szekely, T. (2013). Acoustic signalling in Eurasian penduline tits remiz pendulinus: Repertoire size signals male nest defence. Acta zoologica academiae scientiarum hungaricae, 59(1), 81-96. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. -

Belarus Tour Report 2015

Aquatic Warbler, Sporovo Reserve (all photos taken on the 2015 tour by Mike Watson) BELARUS 13 – 21 May 2015 Northern Belarus Extension from 10 May LEADERS: MIKE WATSON and DIMA SHAMOVICH I was wondering how we could follow our successful first visit to Belarus in 2014... I need not have worried. New for 2015 on our expanded itinerary were: Hazel Grouse (both in the north and the south, including a fe- male on its nest); Western Capercaillie, Black Grouse and Ural and Tengmalm’s Owls on our Northern Belarus pre-tour extension, to the wonderful Krasny Bor reserve on the Russian border and we also enjoyed some great encounters with old favourites, including: point blank views of Corn Crakes; lekking Great Snipes on meadows by the Pripyat River; 46(!) Terek Sandpipers; hundreds of ‘marsh’ terns (White-winged, Black and Whiskered); Great Grey Owl (an even better close encounter than last time!); Eurasian Pygmy Owl; nine spe- cies of woodpecker including White-backed (three) and Eurasian Three-toed (five); Azure Tits at five different sites including our best views yet; Aquatic Warblers buzzing away in an ancient sedge fen (again our best views yet of this rapidly declining bird). With the benefit of the new pre-tour extension to the boreal zone of northern Belarus as well as some good fortune on the main tour we recorded a new high total of 184 bird spe- cies and other avian highlights included: Smew; Black Stork; Greater Spotted, Lesser Spotted and White-tailed Eagles; Northern Goshawk; Wood Sandpipers and Temminck’s Stints on passage in the south and breeding Whimbrels and Common Greenshanks on raised bogs in the north; Eurasian Nightjar; a profusion of song- 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Belarus www.birdquest-tours.com WWII memorial at Sosnovy sters mostly only known to western birders as scarce drift migrants including Wrynecks, Red-backed Shrikes, Marsh, Icterine and River Warblers as well as gaudy Citrine Wagtails and Common Rosefinches and lovely old forests full of Wood Warblers and Red-breasted Flycatchers. -

A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 4 A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts Madeeha Manzoor Center for Bioresource Research Adila Nazli Center for Bioresource Research, [email protected] Sabiha Shamim Center for Bioresource Research Fida Muhammad Khan Center for Bioresource Research Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Manzoor, M., Nazli, A., Shamim, S., & Khan, F. M. (2017). A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts, Journal of Bioresource Management, 4 (1). DOI: 10.35691/JBM.7102.0067 ISSN: 2309-3854 online (Received: May 29, 2019; Accepted: May 29, 2019; Published: Jan 1, 2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts Erratum Added the complete list of author names © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. Journal of Bioresource Management does not grant you any other rights in relation to this website or the material on this website. In other words, all other rights are reserved. For the avoidance of doubt, you must not adapt, edit, change, transform, publish, republish, distribute, redistribute, broadcast, rebroadcast or show or play in public this website or the material on this website (in any form or media) without appropriately and conspicuously citing the original work and source or Journal of Bioresource Management’s prior written permission. -

"Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at Its Meeting Held on ______2007, Enacted This

In accordance with Article 6 paragraph 3 of the FT Law ("Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at its meeting held on ____________ 2007, enacted this DECISION ON CONTROL LIST FOR EXPORT, IMPORT AND TRANSIT OF GOODS Article 1 The goods that are being exported, imported and goods in transit procedure, shall be classified into the forms of export, import and transit, specifically: free export, import and transit and export, import and transit based on a license. The goods referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article were identified in the Control List for Export, Import and Transit of Goods that has been printed together with this Decision and constitutes an integral part hereof (Exhibit 1). Article 2 In the Control List, the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license, were designated by the abbreviation: “D”, and automatic license were designated by abbreviation “AD”. The goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license designated by the abbreviation “D” and specific number, license is issued by following state authorities: - D1: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for protection of human health - D2: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for animal and plant health protection, if goods are imported, exported or in transit for veterinary or phyto-sanitary purposes - D3: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for environment protection - D4: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for culture. -

Comparative Life History of the South Temperate Cape Penduline Tit (Anthoscopus Minutus) and North Temperate Remizidae Species

J Ornithol DOI 10.1007/s10336-016-1417-4 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Comparative life history of the south temperate Cape Penduline Tit (Anthoscopus minutus) and north temperate Remizidae species 1,2 1 1 Penn Lloyd • Bernhard D. Frauenknecht • Morne´ A. du Plessis • Thomas E. Martin3 Received: 19 June 2016 / Revised: 22 October 2016 / Accepted: 14 November 2016 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2016 Abstract We studied the breeding biology of the south parental nestling care. Consequently, in comparison to the temperate Cape Penduline Tit (Anthoscopus minutus)in other two species, the Cape Penduline Tit exhibits greater order to compare its life history traits with those of related nest attentiveness during incubation, a similar per-nestling north temperate members of the family Remizidae, namely feeding rate and greater post-fledging survival. Its rela- the Eurasian Penduline Tit (Remiz pendulinus) and the tively large clutch size, high parental investment and Verdin (Auriparus flaviceps). We used this comparison to associated high adult mortality in a less seasonal environ- test key predictions of three hypotheses thought to explain ment are consistent with key predictions of the adult latitudinal variation in life histories among bird species— mortality hypothesis but not with key predictions of the the seasonality and food limitation hypothesis, nest pre- seasonality and food limitation hypothesis in explaining dation hypothesis and adult mortality hypothesis. Contrary life history variation among Remizidae species. These to the general pattern of smaller clutch size and lower adult results add to a growing body of evidence of the impor- mortality among south-temperate birds living in less sea- tance of age-specific mortality in shaping life history sonal environments, the Cape Penduline Tit has a clutch evolution. -

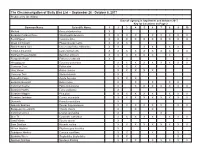

The Circumnavigation of Sicily Bird List -- September 26

The Circumnavigation of Sicily Bird List -- September 26 - October 8, 2017 Produced by Jim Wilson Date of sighting in September and October 2017 Key for Locations on Page 2 Common Name Scientific Name 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X Yellow-legged Gull Larus michahellis X X X X X X X X X X Northern House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X European Robin Erithacus rubecula X X Woodpigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X Common Coot Fulica atra X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X Bonnelli's Eagle Aquila fasciata X X X Eurasian Buzzard Buteo buteo X X X X X Common Kestrel Falco tinnunculus X X X X X X X X Eurasian Hobby Falco subbuteo X Eurasian Magpie Pica pica X X X X X X X X Eurasian Jackdaw Corvus monedula X X X X X X X X X Dunnock Prunella modularis X Spanish Sparrow Passer hispaniolensis X X X X X X X X European Greenfinch Chloris chloris X X X Common Linnet Linaria cannabina X X Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus X X X X X X X X Sand Martin Riparia riparia X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus X Subalpine Warbler Curruca cantillans X X X X Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes X X X Spotless Starling Spotless Starling X X X X X X X X Common Name Scientific Name 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sardinian Warbler Curruca melanocephala X X X X -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, Member of Albatros Media Group, 2020

✹ Tomáš Tůma Tomáš ✹ ✹ We all know that there are many birds in the sky, but did you know that there is a similar Encyclopaedia vast number on our planet’s surface? The bird kingdom is weird, wonderful, vivid ✹ of Birds and fascinating. This encyclopaedia will introduce you to over a hundred of the for Young Readers world’s best-known birds, as well as giving you a clear idea of the orders in which birds ✹ ✹ are classified. You will find an attractive selection of birds of prey, parrots, penguins, songbirds and aquatic birds from practically every corner of Planet Earth. The magnificent full-colour illustrations and easy-to-read text make this book a handy guide that every pre- schooler and young schoolchild will enjoy. Tomáš Tůma www.b4upublishing.com Readers Young Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, member of Albatros Media Group, 2020. ean + isbn Two pairs of toes, one turned forward, ✹ Toco toucan ✹ Chestnut-eared aracari ✹ Emerald toucanet the other back, are a clear indication that Piciformes spend most of their time in the trees. The beaks of toucans and aracaris The diet of the chestnut-eared The emerald toucanet lives in grow to a remarkable size. Yet aracari consists mainly of the fruit of the mountain forests of South We climb Woodpeckers hold themselves against tree-trunks these beaks are so light, they are no tropical trees. It is found in the forest America, making its nest in the using their firm tail feathers. Also characteristic impediment to the birds’ deft flight lowlands of Amazonia and in the hollow of a tree. -

Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas

sustainability Article Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas Vasilios Liordos 1,* , Jukka Jokimäki 2 , Marja-Liisa Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki 2, Evangelos Valsamidis 1 and Vasileios J. Kontsiotis 1 1 Department of Forest and Natural Environment Sciences, International Hellenic University, 66100 Drama, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (V.J.K.) 2 Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland; jukka.jokimaki@ulapland.fi (J.J.); marja-liisa.kaisanlahti@ulapland.fi (M.-L.K.-J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Knowing the ecological requirements of bird species is essential for their successful con- servation. We studied the niche characteristics of birds in managed small-sized green spaces in the urban core areas of southern (Kavala, Greece) and northern Europe (Rovaniemi, Finland), during the breeding season, based on a set of 16 environmental variables and using Outlying Mean Index, a multivariate ordination technique. Overall, 26 bird species in Kavala and 15 in Rovaniemi were recorded in more than 5% of the green spaces and were used in detailed analyses. In both areas, bird species occupied different niches of varying marginality and breadth, indicating varying responses to urban environmental conditions. Birds showed high specialization in niche position, with 12 species in Kavala (46.2%) and six species in Rovaniemi (40.0%) having marginal niches. Niche breadth was narrower in Rovaniemi than in Kavala. Species in both communities were more strongly associated either with large green spaces located further away from the city center and having a high vegetation cover (urban adapters; e.g., Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), European Greenfinch (Chloris Citation: Liordos, V.; Jokimäki, J.; chloris Cyanistes caeruleus Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L.; ), Eurasian Blue Tit ( )) or with green spaces located closer to the city center Valsamidis, E.; Kontsiotis, V.J. -

Phylogeny of the Eurasian Wren Nannus Troglodytes

PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Phylogeny of the Eurasian Wren Nannus troglodytes (Aves: Passeriformes: Troglodytidae) reveals deep and complex diversification patterns of Ibero-Maghrebian and Cyrenaican populations 1 2 3 4 1 Frederik AlbrechtID *, Jens Hering , Elmar Fuchs , Juan Carlos Illera , Flora Ihlow , 5 5 6 7 a1111111111 Thomas J. ShannonID , J. Martin CollinsonID , Michael Wink , Jochen Martens , a1111111111 Martin PaÈckert1 a1111111111 a1111111111 1 Museum of Zoology, Senckenberg Natural History Collections Dresden, Senckenberg|Leibniz Institution for Biodiversity and Earth System Research, Dresden, Saxony, Germany, 2 Verein SaÈchsischer Ornithologen e. a1111111111 V., Limbach-Oberfrohna, Saxony, Germany, 3 Verein SaÈchsischer Ornithologen e.V., Weimar, Thuringia, Germany, 4 Research Unit of Biodiversity (UO-CSIC-PA), Oviedo University, Asturias, Spain, 5 School of Medicine, Medical Sciences and Nutrition, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland, United Kingdom, 6 Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Baden- WuÈrttemberg, Germany, 7 Institute of Organismic and Molecular Evolution, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany OPEN ACCESS Citation: Albrecht F, Hering J, Fuchs E, Illera JC, * [email protected] Ihlow F, Shannon TJ, et al. (2020) Phylogeny of the Eurasian Wren Nannus troglodytes (Aves: Passeriformes: Troglodytidae) reveals deep and complex diversification patterns of Ibero- Abstract Maghrebian and Cyrenaican populations. PLoS The Mediterranean Basin represents a Global Biodiversity Hotspot where many organisms ONE 15(3): e0230151. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0230151 show high inter- and intraspecific differentiation. Extant phylogeographic patterns of terres- trial circum-Mediterranean faunas were mainly shaped through Pleistocene range shifts and Editor: èukasz Kajtoch, Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals Polish Academy of range fragmentations due to retreat into different glacial refugia. -

Penduline Tit Field Guide

PRACTICAL FIELD GUIDE FOR INVESTIGATING BREEDING ECOLOGY OF PENDULINE TITS REMIZ PENDULINUS René E. van Dijk1, István Szentirmai2 & Tamás Székely1 1 Department of Biology & Biochemistry, University of Bath, Bath BA2 7AY, UK 2 Őrsèg National Park, Siskaszer 26a, H-9941, Őriszentpéter, Hungary Email: [email protected] Photograph by C. Daroczi Version 1.5 – 18 Aug 2014 Rationale Why study penduline tits? The main reason behind studying penduline tits is their extremely variable and among birds unusual breeding system: both sexes are sequentially polygamous. Both males and females may desert the clutch during the egg-laying phase, so that parental care is carried out by one parent only and, most remarkably, some 30-40% of clutches is deserted by both parents. In this field guide we outline several methods that help us to reveal various aspects of the penduline tit’s breeding system, including mate choice, mating behaviour, and parental care. The motivation in writing this field guide is to guide you through a number of basic field methods and point your attention to some potential pitfalls. The penduline tit is a fairly easy species to study, but at the heart of unravelling its breeding ecology are appropriate, standardised and accurate field methods. Further reading Cramp, S., Perrins, C. M. & Brooks, D. M. 1993. Handbook of the birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa – The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Franz, D. 1991. Paarungsystem and Fortpflanzungstrategie der Beutelmeise Remiz pendulinus. Journal für Ornithologie, 132, 241-266. Glutz von Blotzheim, U.N. -

England Birds and Gardens 2013 Trip

Eagle-Eye England Birds and Gardens 2013 Trip May 7th – 18th 2013 Bird List Graylag Goose (Anser anser) Dark-bellied Brent Goose (Branta bernicla bernicla)] Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) Mute Swan (Cygnus olor) Egyptian Goose (Alopochen aegyptiaca) Common Shelduck (Tadorna tadorna) Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata) Gadwall (Anas strepera) Eurasian Wigeon (Anas penelope) Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) Northern Shoveler (Anas clypeata) Green-winged Teal (Eurasian) (Anas crecca crecca/nimia) Red-crested Pochard (Netta rufina) Common Pochard (Aythya ferina) Tufted Duck (Aythya fuligula) Common/Northern Eider (Somateria mollissima mollissima) Common Scoter (Melanitta nigra) Red-legged Partridge (Alectoris rufa) Gray Partridge (Perdix perdix) Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) Little Grebe (Tachybaptus ruficollis) Great Crested Grebe (Podiceps cristatus) Northern Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) Northern Gannet (Morus bassanus) Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) Gray Heron (Ardea cinerea) Little Egret (Egretta garzetta) Eurasian Spoonbill (Platalea leucorodia) Western Marsh-Harrier (Circus aeruginosus) Eurasian Sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo) Water Rail (Rallus aquaticus) Eurasian Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus) Eurasian Coot (Fulica atra) Common Crane (Grus grus) Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) Grey/Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) Common Ringed Plover (Charadrius hiaticula) Little Ringed Plover (Charadrius dubius) Eurasian Oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus) Pied Avocet (Recurvirostra avosetta)