Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Trimester 2018

Volume LXXXII, No. 2 • 2nd Trimester 2018 Contents Dream Forward 2 Dream Forward 3Better Together Scholarship Initiative 4King and Kingdon 9Equine Science Exceeds Goal for 13 Leadership Memphis-Area Students 16 Racial Injustice 18 David Potts n partnership with the Ethics as we pursue racial unity in the 22 Annual Meeting Schedule Iand Religious Liberty midst of tremendous tension.” 24 Union’s EDGE Program Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, IABCU insti- The Dream Forward Scholarship 28 Williams Baptist College tutions participated in the Initiative seeks to partner Christian colleges and seminar- 30 Legal Notes Dream Forward Scholarship Initiative. Dream Forward was ies to invest in the educational 33 Charleston Southern University created as part of the MLK50 future of minority students. The Conference, a joint venture of centerpiece of this effort is the Vol. LXXXII, No. 2 the ERLC and The Gospel creation of new pathways to a 2nd Trimester 2018 Coalition. quality higher education through an array of full and partial Publisher: Barbara McMillin, President and Board Chair, IABCU From the conference site, “Racial tuition scholarships at participat- Managing Editor Ashley Hill, unity is a gospel issue and all the ing Christian colleges and uni- Executive Secretary, IABCU more urgent 50 years after versities around the country The Baptist Educator (ISSN 0038-3848) is a reserved exclusively for minority news magazine published three times a year Martin Luther King Jr.’s for administrators, faculty, staff, trustees and death.The 50th anniversary of students in Memphis. The goal is friends of member schools by the King’s tragic death marks an to equip these students to return International Association of Baptist Colleges and Universities. -

Third Trimester 2019

Volume LXXXIII, No. 3 • 3rd Trimester 2019 Robertson/Farmer/Hester 2Educational Funds 3Lessons Learned 5Annual Meeting EDUCATIONAL FUNDS 6NOBTS 8 Hawkins Speech 14 Call for Papers 15 Legal Update Available to 16 BCU Scholars 18 BSIR Update 19 IABCU Officers/Board IABCU FACULTY AND 20 Drowning in Red 24 Revenue Enhancing Opportunities ADMINISTRATORS To pursue Doctoral Degrees Vol. LXXXIII, No. 3 3rd Trimester 2019 Publisher: Ron Ellis, President and Board Chair, IABCU Managing Editor Ashley Hill, Executive Secretary, IABCU The Baptist Educator (ISSN 0038-3848) is a news magazine published three times a year for administrators, faculty, staff, trustees and obertson/Farmer/Hester mer term. friends of member schools by the REducational Loan funds International Association of Baptist Colleges designed to assist full-time fac- The loans are to be paid back in and Universities. service at a qualifying Southern POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: ulty or administrators at quali- International Association of Baptist Colleges fying Southern Baptist-related Baptist school at the rate of and Universities (IABCU) $2,000 per academic year. If a Samford University educational institutions to P. O. B ox 2 9 3 9 3 5 obtain their doctoral degrees loan recipient ceases to be Birmingham, AL 35229 and postdoctoral study/research employed by a qualifying Send news items to: Southern Baptist educational Executive Secretary are available from the Southern The Baptist Educator Baptist Foundation. institution for any reason or E-mail: [email protected] fails to complete the degree in IABCU Samford University Applicants are required to be five years the loan must be paid P. -

2018-2019 Academic Catalog

2018-2019 Academic Catalog 1 Table of Contents From the President 5 Our Mission 5 Essential Leadership Competencies 6 The Baptist Faith and Message 8 A Covenant Between Our Seminaries and Our Churches 15 Policy Statement 17 Faculty Role in Institutional Governance 18 Accreditation 19 Contact Information 22 Degree Overview 23 Online Program Overview 26 Korean-English Bilingual Program 27 Master of Divinity - KEB 28 Master of Missiology - KEB 30 Master of Theological Studies - KEB 32 Master of Arts in Educational Leadership - KEB 34 Chinese-English Bilingual Program 36 Master of Divinity - CEB 37 Master of Theological Studies - CEB 39 Master of Divinity 41 Mentored Master of Divinity 44 Master of Divinity — Advanced Track 47 Master of Divinity — Biblical Studies Concentration 49 Master of Divinity — Chaplaincy Concentration 51 Master of Divinity — Children's Ministry Concentration 53 Master of Divinity — Christian Counseling Concentration 55 Master of Divinity — Church Planting Concentration 57 Master of Divinity — Collegiate Ministry Concentration 59 Master of Divinity — Educational Leadership Concentration 61 Master of Divinity — Intercultural Studies Concentration 63 Master of Divinity — Ministry to Women Concentration 65 Master of Divinity — Missiology Concentration 67 Master of Divinity — Spiritual Formation Concentration 69 Master of Divinity — Theological-Historical Studies Concentration 71 Master of Divinity — Youth Ministry Concentration 73 Master of Missiology 75 Master of Theological Studies 77 Master of Arts in Christian Counseling -

2016-2017 Academic Catalog Table of Contents

2016-2017 Academic Catalog Table of Contents From the President 5 Our Mission 5 Essential Leadership Characteristics 6 The Baptist Faith and Message 8 A Covenant Between Our Seminaries and Our Churches 15 Policy Statement 17 Faculty Role in Institutional Governance 18 Accreditation 19 Contact Information 21 Degree Overview 22 Online Program Overview 25 Korean-English Bilingual Program 26 Master of Divinity - KEB 27 Master of Theological Studies - KEB 29 Master of Divinity 31 Mentored Master of Divinity 34 Master of Divinity - Advanced Track 37 Master of Divinity - Biblical Studies Concentration 38 Master of Divinity - Chaplaincy Concentration 40 Master of Divinity - Christian Counseling Concentration 42 Master of Divinity - Church Planting Concentration 44 Master of Divinity - Collegiate Ministry Concentration 46 Master of Divinity - Educational Leadership Concentration 48 Master of Divinity - Global Missiology Concentration 50 Master of Divinity - Spiritual Formation Concentration 52 Master of Divinity - Theological-Historical Studies Concentration 54 Master of Divinity - Urban Missiology Concentration 56 Master of Divinity - Youth Ministry Concentration 58 Master of Missiology 60 Master of Theological Studies 62 Master of Arts in Christian Counseling 64 Master of Arts in Educational Leadership 66 Master of Arts in Intercultural Studies 68 Master of Theology 70 Doctor of Philosophy 74 Doctor of Ministry 79 Diploma in Educational Leadership 85 Diploma in Theology 87 Certificate Program Overview 89 Bible Teaching Certificate 90 Church Planting -

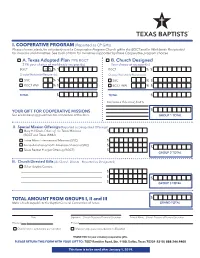

I. COOPERATIVE PROGRAM (Reported As CP

I. COOPERATIVE PROGRAM (Reported as CP Gifts) Please choose plan(s) to voluntarily send a Cooperative Program Church gift to the BGCT and/or Worldwide Recipient(s) for missions and ministries. See back of form for ministries supported by these Cooperative program choices. A. Texas Adopted Plan 79% BGCT B. Church Designed 21% your choice of worldwide recipient(s) Your choice of recipient(s) BGCT 7 9 % $ . BGCT % $ . Choose Worldwide Recipient(s) Choose Worldwide Recipient(s) . SBC % $ SBC % $ BGCT WW % $ . BGCT WW % $ . TOTAL $ . TOTAL $ . Exclusions if desired, limit 5 YOUR GIFT FOR COOPERATIVE MISSIONS $ . See accompanying guidelines for completion of this form. GROUP 1 TOTAL II. Special Mission Offerings (Reported as Designated Offerings) Mary Hill Davis Offering® for Texas Missions $ . (BGCT and Texas WMU) Lottie Moon International Missions (SBC) $ . Annie Armstrong North American Missions (SBC) $ . $ . Texas Baptist Hunger Offering (BGCT) $ . GROUP 2 TOTAL III. Church Directed Gifts (As Church Directs – Reported as Designated) Other Baptist Causes: _____________________________________________ $ . _____________________________________________ . $ $ . _____________________________________________ $ . GROUP 3 TOTAL TOTAL AMOUNT FROM GROUPS I, II and III $ . Make checks payable to the Baptist General Convention of Texas. GRAND TOTAL Date Signature – Church Treasurer/Financial Secretary Printed Name – Church Treasurer/Financial Secretary Phone ( ) E-mail Check here if new forms are needed Marque aqui para formularios en Español THANK YOU -

Dallas C. Bivins, Dmin, Edd Director of the Arizona Campus Professor of Ministry Leadership Gateway Seminary

Dallas C. Bivins, DMin, EdD Director of the Arizona Campus Professor of Ministry Leadership Gateway Seminary [email protected] I have taught leadership, management and biblical studies on the Bachelor and Master levels; Spiritual Formations on the Master and Doctoral level; and physical education and athletic coaching on the high school and college levels. Areas of Concentration: Leadership, management, administration, biblical studies Areas of Specialty: Servant leadership, visionary leadership, coaching, team-building and group dynamics, relationships, conflict resolution and mediation. Education D.Min., Leadership Coaching, Gateway Seminary, 2012 Project: Effective use of a Transformation Team Ed.D., Leadership Studies, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2005 Dissertation: Servant Leadership and Ministry Satisfaction in Church Leaders M.A.R.E., Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1993 B.A., Social Sciences, Grand Canyon University, 1989 Teaching Experience Professor of Ministry Leadership, Gateway Seminary, 2013-present Adjunct Professor, Leadership and biblical studies, Wayland Baptist University, 2004-5 Adjunct Professor, Leadership and biblical studies, Oklahoma Baptist University, 1995-6 Football and Strength Coach, Instructor in physical education, Phoenix College, 1988 Ministry Experience Director, Sullivan Baptist Association, Kingsport, Tennessee, 2006-13 Director, Chugach Baptist Association, Anchorage, Alaska, 2002-06 Director, Baptist Collegiate Ministries, University of Alaska, 2001-02 Teaching Pastor, Grand -

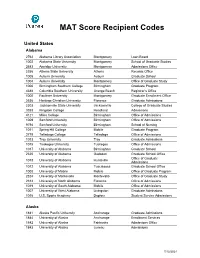

MAT Score Recipient Codes

MAT Score Recipient Codes United States Alabama 2762 Alabama Library Association Montgomery Loan Board 1002 Alabama State University Montgomery School of Graduate Studies 2683 Amridge University Montgomery Admissions Office 2356 Athens State University Athens Records Office 1005 Auburn University Auburn Graduate School 1004 Auburn University Montgomery Office of Graduate Study 1006 Birmingham Southern College Birmingham Graduate Program 4388 Columbia Southern University Orange Beach Registrar’s Office 1000 Faulkner University Montgomery Graduate Enrollment Office 2636 Heritage Christian University Florence Graduate Admissions 2303 Jacksonville State University Jacksonville College of Graduate Studies 3353 Kingdom College Headland Admissions 4121 Miles College Birmingham Office of Admissions 1009 Samford University Birmingham Office of Admissions 9794 Samford University Birmingham School of Nursing 1011 Spring Hill College Mobile Graduate Program 2718 Talladega College Talladega Office of Admissions 1013 Troy University Troy Graduate Admissions 1015 Tuskegee University Tuskegee Office of Admissions 1017 University of Alabama Birmingham Graduate School 2320 University of Alabama Gadsden Graduate School Office Office of Graduate 1018 University of Alabama Huntsville Admissions 1012 University of Alabama Tuscaloosa Graduate School Office 1008 University of Mobile Mobile Office of Graduate Program 2324 University of Montevallo Montevallo Office of Graduate Study 2312 University of North Alabama Florence Office of Admissions 1019 University -

I. COOPERATIVE PROGRAM (Reported As CP Gifts

I. COOPERATIVE PROGRAM (Reported as CP Gifts) Please choose plan(s) to voluntarily send a Cooperative Program Church gift to the BGCT and/or Worldwide Recipient(s) for missions and ministries. See back of form for ministries supported by these Cooperative Program choices. A. Texas Adopted Plan 79% BGCT B. Church Designed 21% your choice of worldwide recipient(s) Your choice of recipient(s) BGCT 7 9 % $ . BGCT % $ . Choose Worldwide Recipient(s) Choose Worldwide Recipient(s) SBC % $ . SBC % $ . BGCT WW % $ . BGCT WW % $ . TOTAL $ . TOTAL $ . Exclusions if desired, limit 5 YOUR GIFT FOR COOPERATIVE MISSIONS $ . See accompanying guidelines for completion of this form. GROUP 1 TOTAL II. Special Mission Offerings (Reported as Designated Offerings) Mary Hill Davis Offering® for Texas Missions $ . (BGCT and Texas WMU) Lottie Moon International Missions (SBC) $ . Annie Armstrong North American Missions (SBC) $ . $ . Texas Baptist Hunger Offering (BGCT) $ . GROUP 2 TOTAL III. Church Directed Gifts (As Church Directs – Reported as Designated) Other Baptist Causes: ___________________________________ $ . ___________________________________ $ . $ . ___________________________________ $ . GROUP 3 TOTAL TOTAL AMOUNT FROM GROUPS I, II and III $ . Make checks payable to the Baptist General Convention of Texas. GRAND TOTAL Date Signature – Church Treasurer/Financial Secretary Printed Name – Church Treasurer/Financial Secretary Phone ( ) E-mail Check here if new forms are needed Marque aqui para formularios en Español THANK YOU for your voluntary cooperative -

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 16TH 9:00 AM to 12:10 PM 8:15 AM - 8:45 AM Morning Prayer Omni - Texas Ballroom EF Join Us for a Simple Worship Service of Scripture and Prayer

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 16TH 9:00 AM TO 12:10 PM 8:15 AM - 8:45 AM Morning Prayer Omni - Texas Ballroom EF Join us for a simple worship service of scripture and prayer P - 9:00 AM - 12:10 PM Christianity and Culture Theology and Apologetics in a Pluralistic World Omni - Stockyard 1 Moderator: John Adair (Dallas Theological Seminary) 9:00 AM – 9:40 AM Daniel T. (Danny) Slavich (Cross United Church) A Credible Witness: A Pluriform Church in a Pluralist Culture 9:50 AM – 10:30 AM SuYeon Yoon (Boston University, Center for Global Christianity and Mission) Effects of Culture on Neo-Charismatic Christianity in S. Korea and N. America from 1980s-Present 10:40 AM – 11:20 AM Jeffrey M. Robinson (Grace Fellowship: A Church for All Nations) Persuasive Apologetics: Truth and Tone 11:30 AM – 12:10 PM Daniel K. Eng (Western Seminary) East Asian and Asian American Reflections on the Epistle of James P - 9:00 AM - 12:10 PM Hermeneutics The Canon and Biblical Interpretation Omni - Fort Worth Ballroom 4 Moderator: Scott Duvall (Ouachita Baptist University) 9:00 AM – 9:30 AM Stephen Dempster (Crandall University) Canon and Context: The Hermeneutical Significance of Canonical Sequence 16 TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 16TH 9:00 AM TO 12:10 PM 9:35 AM – 10:05 AM Darian Lockett (Talbot School of Theology) Interpreting the New Testament as Canon: Whose Intention and What Context? 10:10 AM – 10:25 AM Respondent: Matthew S. Harmon (Grace College & Theological Seminary) 10:25 AM – 10:40 AM Respondent: Patrick Schreiner (Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary) 10:40 AM – 10:55 AM Respondent: Matthew Barrett (Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary) 11:00 AM – 12:10 PM Panel Discussion P - 9:00 AM - 12:10 PM Method in Systematic Theology Methodologies Comparative and Doctrinal Omni - Fort Worth Ballroom 5 Moderator: John C. -

SUMMARY of PROCEEDINGS

SUMMARY of PROCEEDINGS Seventy-second Annual Conference of the American Theological Library Association Miranda Bennett EDITOR American Theological Library Association ISSN: 0066-0868 INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA JUNE 13-16, 2018 © American Theological Library Association 300 S. Wacker Drive Suite 2100 Chicago, IL 60606-6701 [email protected] ISSN 0066-0868 Summary of Proceedings is an open access serial publication of ATLA and hosted on the Open Journals Systems at https://serials. atla.com/proceedings. Proceedings is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (CC-BY-NC 4.0 https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode). Each individual author has retained copyright to their submission pursuant to the Presenter Agreement; ATLA holds copyright in the compiled Summary of Proceedings and in content authored by or at the direction of ATLA staff. Welcome from the Local Host Committee KNOWN AS THE CROSSROADS OF AMERICA, Indianapolis is within a day’s drive of over half of the country’s population. This year’s conference setting provides an opportunity to share a ride and a room with another member of your library team or to bring your family along. Situated in the heart of Indy, our conference hotel, the Hyatt Regency, is within walking distance of many top attractions and restau- rants. A skywalk connects the hotel to Circle Centre Mall, featuring ninety stores and services. For those traveling with families, the top ten-rated Indianapolis Zoo and White River Gardens is a thirty-minute walk. Both the Indi- anapolis Children’s Museum, the world’s biggest and best, and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Museum, home of the Indianapo- lis 500, are a fourteen-minute drive. -

2019 Exhibitors - SBTC Annual Meeting

2019 Exhibitors - SBTC Annual Meeting Exhibitor Name Booth Number Alto Frio Baptist Camp 23 Circle Six Baptist Camp 25 Criswell College (2) 11 Gateway Seminary of the Southern Baptist Convention 16 GuideStone Financial Resources (2) 30 Hendrick Mission Center 31 Highland Lakes Camp & Conference Center (3) 22 International Mission Board 14 Jacksonville College 12 Lake Lavon Baptist Encampment 24 LifeWay Christian Resources 10 Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 19 MinistrySafe 6 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary 17 North American Mission Board 15 Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary 18 Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 21 Texas Baptist Camping Association 26 Texas Baptist Home for Children 13 The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary 20 SBTC Booths SBTC - Church Ministries (4) 5 SBTC - Church Revitalization (1) 1 SBTC - Evangelism (5) 3 & 4 SBTC - Foundation (2) 2 SBTC - SBTC En Espanol (2) 9 SBTC - Missions (5) 8 SBTC - Pastor/Church Relations (2) 7 Other SBTC - Cooperative Program (2) Commons SBC Tapes Commons By Name 2019 Exhibitors - SBTC Annual Meeting Exhibitor Name Booth Number SBTC - Church Revitalization (1) 1 SBTC - Foundation (2) 2 SBTC - Evangelism (5) 3 & 4 SBTC - Church Ministries (4) 5 MinistrySafe 6 SBTC - Pastor/Church Relations (2) 7 SBTC - Missions (5) 8 SBTC - SBTC En Espanol (2) 9 LifeWay Christian Resources 10 Criswell College (2) 11 Jacksonville College 12 Texas Baptist Home for Children 13 International Mission Board 14 North American Mission Board 15 Gateway Seminary of the Southern Baptist Convention 16 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary 17 Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary 18 Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 19 The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary 20 Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 21 Highland Lakes Camp & Conference Center (3) 22 Alto Frio Baptist Camp 23 Lake Lavon Baptist Encampment 24 Circle Six Baptist Camp 25 Texas Baptist Camping Association 26 GuideStone Financial Resources (2) 30 Hendrick Mission Center 31 By Number. -

2019 Exhibitors - SBTC Annual Meeting

2019 Exhibitors - SBTC Annual Meeting Exhibitor Name Booth Number Alto Frio Baptist Camp 23 Basin Baptist Network 27 Circle Six Baptist Camp 25 Criswell College (2) 11 Gateway Seminary of the Southern Baptist Convention 17 GuideStone Financial Resources (2) 30 Hendrick Mission Center 31 Highland Lakes Camp & Conference Center (3) 22 International Mission Board 14 Jacksonville College 12 Lake Lavon Baptist Encampment 24 LifeWay Christian Resources 10 Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 19 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary 18 North American Mission Board 15 Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 21 Texas Baptist Camping Association 26 Texas Baptist Home for Children 13 The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary 20 SBTC Booths SBTC - Church Ministries (4) 5 SBTC - Church Revitalization 1 SBTC - Evangelism (5) 3 & 4 SBTC - Foundation (2) 2 SBTC - Missions (5) 8 SBTC - Pastor/Church Relations (3) 6 & 7 SBTC - SBTC En Espanol (2) 9 SBTC - TERLC 29 Other SBTC - Cooperative Program (2) Commons SBC Tapes Commons By Name 2019 Exhibitors - SBTC Annual Meeting Exhibitor Name Booth Number SBTC - Church Revitalization (1) 1 SBTC - Foundation (2) 2 SBTC - Evangelism (5) 3 & 4 SBTC - Church Ministries (4) 5 SBTC - Pastor/Church Relations (3) 6 & 7 SBTC - Missions (5) 8 SBTC - SBTC En Espanol (2) 9 LifeWay Christian Resources 10 Criswell College (2) 11 Jacksonville College 12 Texas Baptist Home for Children 13 International Mission Board 14 North American Mission Board 15 Gateway Seminary of the Southern Baptist Convention 17 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary 18 Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 19 The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary 20 Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary 21 Highland Lakes Camp & Conference Center (3) 22 Alto Frio Baptist Camp 23 Lake Lavon Baptist Encampment 24 Circle Six Baptist Camp 25 Texas Baptist Camping Association 26 Basin Baptist Network 27 SBTC - Texas Ethics & Religious Liberty Committee 29 GuideStone Financial Resources (2) 30 Hendrick Mission Center 31 By Number.