A Cave of Their Own: a Comparative Examination of Recurring Social And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art James Anthony Ricci University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-15-2015 Now, We Hear Through a Voice Darkly: New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art James Anthony Ricci University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ricci, James Anthony, "Now, We Hear Through a Voice Darkly: New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6021 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Now, We Hear Through a Voice Darkly: New Media and Narratology in Cinematic Art by James A. Ricci A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Victor Peppard, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 13, 2015 Keywords: New Media, Narratology, Manovich, Bakhtin, Cinema Copyright © 2015, James A. Ricci DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my wife, Ashlea Renée Ricci. Without her unending support, love, and optimism I would have gotten lost during the journey. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe many individuals much gratitude for their support and advice throughout the pursuit of my degree. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Petr Husseini Nick Cave’s Lyrics in Official and Amateur Czech Translations Master‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph.D. 2009 Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. .................................................. Author‟s signature 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph.D., for her kind help, support and valuable advice. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 1. Translation of Lyrics and Poetry .............................................................................. 9 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 9 1.2 General Nature of Lyrics and Poetry ........................................................ 11 1.3 Tradition of Lyrics Translated into Czech ............................................... 17 1.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 20 2. Nick Cave’s Lyrics in King Ink and King Ink II ................................................... 22 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 22 -

Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave

Student ID: XXXXXX ENGL3372: Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave Table of Contents Introduction 2 Chapter One – ‘I went on down the road’: Cave and the holy blues 4 Chapter Two – ‘I got the abattoir blues’: Cave and the contemporary 15 Chapter Three – ‘Can you feel my heart beat?’: Cave and redemptive feeling 25 Conclusion 38 Bibliography 39 Appendix 44 Student ID: ENGL3372: Dissertation 12 May 2014 Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the lyrics of Nick Cave Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown INTRODUCTION And I only am escaped to tell thee. So runs the epigraph, taken from the Biblical book of Job, to the Australian songwriter Nick Cave’s collected lyrics.1 Using such a quotation invites anyone who listens to Cave’s songs to see them as instructive addresses, a feeling compounded by an on-record intensity matched by few in the history of popular music. From his earliest work in the late 1970s with his bands The Boys Next Door and The Birthday Party up to his most recent releases with long- time collaborators The Bad Seeds, it appears that he is intent on spreading some sort of message. This essay charts how Cave’s songs, which as Robert Eaglestone notes take religion as ‘a primary discourse that structures and shapes others’,2 consistently use the blues as a platform from which to deliver his dispatches. The first chapter draws particularly on recent writing by Andrew Warnes and Adam Gussow to elucidate why Cave’s earlier songs have the blues and his Christian faith dovetailing so frequently. -

Photo Credit: Kevin Kauer, Pictured: Original Cast Photo Credit: Nate Watters, Pictured: 2015 Cast

Photo Credit: Kevin Kauer, Pictured: Original Cast Photo Credit: Nate Watters, Pictured: 2015 Cast A Glimmer of Hope or Skin or Light (Glimmer) was a dance/theater/cabaret/glam-rock musical commissioned by Seattle’s ACT Theatre and performed to sold out houses in 2010 and again in 2015 created by veteran choreographer/director KT Niehoff. Glimmer was described by Michael Van Baker from the SunBreak as “one of the more spectacular, unpredictable, and mood-altering performances (he’s) ever been a party to.” The cast entwined with an audience that was free to watch the show from any vantage point, moving as they wish throughout the evening. Full of uncommon encounters, raucous spectacle and virtuosic dancing, Gigi Berardi of Dance Magazine wrote, “(Glimmer) is a raucous, daunting thing…. and unforgettable.” The cast was comprised of five core dancers, seven showgirls and a rock band led by singer/songwriter Ivory Smith. Niehoff and Smith fronted the band, singing original songs that borrowed inspiration from Pippin, Cabaret, and Moulin Rouge. Audience member Bret Love said, “I had no idea that something so beautiful and perfect existed. And that one night spent in their world literally changed my life.” Glimmer’s original Seattle luminary cast: Bianca Cabrera, Ricki Mason, Aaron Swartzman, Kelly Sullivan and Michael Rioux. Showgirls: Sruti Desai, Jill Leversee, Morgan Nutt, Erin Simons, Violette Tucker, Hendri Walujo and Kate Wallich Glimmer’s 2015 all-star international cast: Meredith Salle, Patrick Kilbane, Amy Tuner Clem, Ainesh Madan, Antonio Somera Jr. and Molly Sides. Showgirls: Danica Bito, Emily Durand, Nadia Losonsky, Annie McGhee, Anja Kellner Rogers and Hendri Walujo. -

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Artist Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

360 - Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} Anna Lunoe & Wax Motif - Love Ting 360 - Child Antlers, The - I Don't Want Love 360 - Falling & Flying Architecture In Helsinki - Break My Stride {Like A Version} 360 - I'm OK Architecture In Helsinki - Contact High 360 - Killer Architecture In Helsinki - Denial Style 360 - Meant To Do Architecture In Helsinki - Desert Island 360 - Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} Architecture In Helsinki - Escapee [Me] - Naked Architecture In Helsinki - I Know Deep Down 2 Bears, The - Work Architecture In Helsinki - Sleep Talkin' 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Architecture In Helsinki - W.O.W. A.A. Bondy - The Heart Is Willing Architecture In Helsinki - Yr Go To Abbe May - Design Desire Arctic Monkeys - Black Treacle Abbe May - Taurus Chorus Arctic Monkeys - Don't Sit Down Cause I've Moved Your About Group - You're No Good Chair Active Child - Hanging On Arctic Monkeys - Library Pictures Adalita - Burning Up {Like A Version} Arctic Monkeys - She's Thunderstorms Adalita - Hot Air Arctic Monkeys - The Hellcat Spangled Shalalala Adalita - The Repairer Argentina - Bad Kids Adrian Lux - Boy {Ft. Rebecca & Fiona} Art Brut - Lost Weekend Adults, The - Nothing To Lose Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! Afrojack & Steve Aoki - No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Art Vs Science - Bumblebee Agnes Obel - Riverside Art Vs Science - Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger {Like A Albert Salt - Fear & Loathing Version} Aleks And The Ramps - Middle Aged Unicorn On Beach With Art Vs Science - Higher Sunset Art Vs Science - Meteor (I Feel Fine) Alex Burnett - Shivers {Straight To You: triple j's tribute To Art Vs Science - New World Order Nick Cave} Art Vs Science - Rain Dance Alex Metric - End Of The World {Ft. -

Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman AN ELECTRONIC CLASSICS SERIES PUBLICATION Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman is a publication of The Electronic Classics Series. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any pur- pose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsibility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, The Electronic Clas- sics Series, Jim Manis, Editor, PSU-Hazleton, Hazleton, PA 18202 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them. Jim Manis is a faculty member of the English Depart- ment of The Pennsylvania State University. This page and any preceding page(s) are restricted by copyright. The text of the following pages are not copyrighted within the United States; however, the fonts used may be. Cover Design: Jim Manis; image: Walt Whitman, age 37, frontispiece to Leaves of Grass, Fulton St., Brooklyn, N.Y., steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost da- guerreotype by Gabriel Harrison. Copyright © 2007 - 2013 The Pennsylvania State University is an equal opportunity university. Walt Whitman Contents LEAVES OF GRASS ............................................................... 13 BOOK I. INSCRIPTIONS..................................................... 14 One’s-Self I Sing .......................................................................................... 14 As I Ponder’d in Silence............................................................................... -

Stephen Petronio Company

presents STEPHEN PETRONIO COMPANY Friday, June 15 & Saturday, June 16, 2012 at 8 pm Durham Performing Arts Center UNDERLAND Concept and Choreography Stephen Petronio Music Nick Cave Courtesy of EMI Music, Film & TV and Mute Song Ltd. Music Producer Tony Cohen Soundscape Paul Healy Costumes Tara Subkoff Visual Design Ken Tabachnick Video Mike Daly Assistant to the Artistic Director Gino Grenek Lighting Supervisor Joe Doran Production Stage Manager Veronica Falborn Performed by Stephen Petronio Company with Guest Artists Brandon Collwes & Reed Luplau Descent into Underland Stephen Petronio Mah Sanctum Davalois Fearon & Reed Luplau Mercy Strings Gino Grenek Wild World The Company Wild Wild World The Company The Carny Davalois Fearon, Joshua Green, Gino Grenek, Barrington Hinds, Natalie Mackessy, Jaqlin Medlock, Nicholas Sciscione, Emily Stone, Joshua Tuason Prelude to Weep Emily Stone The Weeping Song Davalois Fearon, Joshua Green, Barrington Hinds, Reed Luplau, Natalie Mackessy, Jaqlin Medlock, Nicholas Sciscione, Joshua Tuason The Ship Song: Davalois Fearon, Gino Grenek, Emily Stone, Joshua Tuason Stagger Lee: Duet: Barrington Hinds & Natalie Mackessy Quartet: Gino Grenek, Reed Luplau, Nicholas Sciscione, Joshua Tuason After Lee Solo: Joshua Green; The Company The Mercy Seat The Company Prelude to Death Davalois Fearon Death is Not the End The Company Running time: 60 minutes, performed without an intermission Casting subject to change UNDERLAND was commissioned by the Sydney Dance Company and had its world premiere at the Sydney Opera House on May 27, 2003. UNDERLAND has been made possible by the National Endowment for the Arts as part of American Masterpieces: Three Centuries of Artistic Genius. This presentation of Underland is made possible by the New England Foundation for the Arts’ National Dance Project, with lead funding from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and additional funding from The Andrew W. -

Villagevoice Review 2011

Stephen Petronio Ventures Into a Dark World By Deborah Jowitt Wednesday, Apr 13 2011 For once, I didn’t read the program. When the lights came Amanda Wells (in up on Stephen Petronio’s Underland, I watched videos of a sky blue tutu) fiery explosions on the three-paneled back wall of the Joyce walk with doll-like stage, heard crashes, and thought of the earthquake in stiffness. Japan. When Reed Luplau descended from above, head Cave sings of the first, harnessed, and clinging to a cargo net, I saw Orpheus shabby circus entering the Underworld to find Eurydice. The burning troupe trying to buildings and circling helicopters in Mike Daly’s video bury the Carny’s montage, as well as the drastic lighting (visual design by dead horse, Ken Tabachnik), seemed part ancient fable and part Sorrow; the shockingly contemporary vision dancers (including Julian De Leon As the piece unfolded, however, it became clear that and Barrington Petronio had in mind other disasters, other hells, and the Hinds) lift Wells subterranean, subcutaneous land of dark minds and dark overhead, laid out, and carry her toward the dark at the deeds. No heroes except the valiant dancers daring to enter back of the stage. the maelstrom. The gothic songs of the Australian Nick Cave thread through a dire soundscape of elements Is it my imagination that when, to heavy piano chords, Wells sampled and manipulated by Tony Cohen from the performs (magnificently) the fierce gestures of the solo recordings of Cave and his band, the Bad Seeds. The “Prelude to Weep,” her eyes look like dark pits? And in “The singer’s voice moans tales of death by execution, sadistic Weeping Song” that follows, the dancers, wearing shabby sex, murder, the sorrows of life, and possible redemption gray clothes, enter in a line, marching numbly; however like wind rushing around an underground cavern. -

2 Column Indented

22,000 Karaoke Songs - AMS Entertainment ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years Duck And Run 6188 Through The Iris 20005 Here By Me 17629 Wasteland 16042 Here Without You 13010 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 10,000 Maniacs Kryptonite 6190 Because The Night 1750 Landing In London 17631 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Let Me Be Myself 25227 Like The Weather 16149 Let Me Go 13785 More Than This 16150 Live For Today 13648 These Are The Days 1273 Loser 6192 Trouble Me 16151 Road I'm On, The 6193 So I Need You 17632 10cc When I'm Gone 13086 Donna 20006 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 30 Seconds To Mars I'm Mandy 16152 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 I'm Not In Love 2631 Rubber Bullets 20007 311 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 All Mixed Up 16156 Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Don't Tread On Me 13649 First Straw 22322 112 Love Song 22323 Come See Me 25019 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Dance With Me 22319 It's Over Now 22320 38 Special Peaches & Cream 22321 Caught Up In You 1904 U Already Know 13602 Hold On Loosely 1901 Second Chance 17633 2 Tons O' Fun Teacher, Teacher 13492 It's Raining Men (Hallelujah!) 6017 3LW 2 Unlimited No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 11795 No Limits 6183 3Oh!3 20 Fingers Don't Trust Me 16157 Short Dick Man 1962 3OH!3 & Katy Perry 2Pac Starstrukk 25138 California Love (Original Version) 14147 Changes 12761 4 Him Ghetto Gospel 16153 Basics Of Life 20002 For Future Generations 20003 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

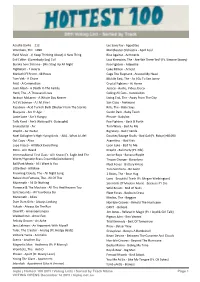

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft. -

Wavelength (January 1982)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 1-1982 Wavelength (January 1982) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (January 1982) 15 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW ORLEANS MUSIC MAGAZINE ISSUE NO. 15 • JANUARY 1982 • $1 .50 (70p U.K.) ISSUE NO. 15 • JANUARY 1982 "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. " Ernie K-Doe, 1979 Features ADen Toussaint . ...... ....... 8 Amusement Tax . ............. 14 Top Cats .. .. ............... 17 Clark Vreeland . .............. 19 N.O.M.I.F.. ................. 23 Bessie Griffin . .. ........... 27 Columns Top20 ................... .. 5 January ............ ......... 7 Jazz ... .. .... .. ... .. .. .... 31 Books ................ ..... 33 Rare Records . ........... .. ... 34 Reggae ... .. .... ........... 35 Reviews ............ ....... .. 37 Classij7eds ... ........... .. .. 44 LastJ>age ................ .... 46 has a divine white wine named after him. Cover photo of Allen Toussaint by Josephine Sacabo THE BISHOP OF RIESLING. Let history pour forth by gracing your table with a bottle of The Bishop . ........._,Patrick Berry, Utor, Connie Atkinson. ~lo Utor, Tim Lyman. A....... Seloo, Steve Gifford, EIJcn Johnson. AJt Over 200 years ago Clemens Wenzelaus von Wettin, Archbishop of Trier, Dlndor, Skip Bolen. Cotolltlolllllla Artlola, Katblccn Perry, Rick Sptin, Mike Staau. Dloertktloll, Gene Sc:aramlllZO, Star Irvine. Co• encouraged the planting of the noble Riesling grape in the picturesque triNe- Steve Alleman, Carlot BoU, Bill CatalancUo, Tanya Coyle, John Deoplu, Zeke Fisbhad, Steve Graves, Jerry Karp, Brad valley of the Mosel. -

U N I V E R S I T Ä T P a D E R B O R N

U n i v e r s i t ä t P a d e r b o r n Fakultät für Kulturwissenschaften Institut für Evangelische Theologie „And God is never far away“ – Spannende Theologie im Werk von Nick Cave Dissertationsschrift von Matthias Surall Am Laugrund 3 33098 Paderborn Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Harald Schroeter-Wittke, Institut für Evangelische Theologie an der Fakultät für Kulturwissenschaften der Universität Paderborn Zweitgutachterin: Privatdozentin Dr. Inge Kirsner, Institut für Evangelische Theologie an der Fakultät für Kulturwissenschaften der Universität Paderborn Mai 2014 Inhaltsverzeichnis I Vorwort V Abkürzungsverzeichnis VII 1. „He’s a ghost, he’s a god, he’s a man, he’s a guru” – Einleitung 1 1.1 Aufmerksame Gespanntheit, erregte Erwartung und fesselnde Entsprechung oder: spannende Zuordnungen und Relationen – Spannung als Kategorie 1 1.2 Angst vor dem Stillstand – Nick Caves biographische Fortentwicklung und künstlerische Wandlungsfähigkeit 3 1.3 Theologie in der Kunst und speziell in der Popkultur? Aspekte und Facetten spannender Theologie im Werk des Laientheologen Nick Cave 6 1.4 Methodische und hermeneutische Prolegomena 9 1.5 Zum Forschungsstand 11 1.5.1 Selbstverortung im bisherigen Diskurs zu Nick Cave 11 1.5.2 Anschluss an die Wahrnehmung und Erforschung popkultureller Phänomene in der Praktischen Theologie 24 2. Vom heiligen Huckleberry bis zum grabenden Lazarus. Das Hauptwerk. 27 2.1 „City of Refuge“ - Die Alben der Berliner Periode von 1984 – 1988 27 2.1.1 „Deep in the Desert of Despair“ – Von (Liebes)Leid und Ewigkeit oder „From