The Salterns of the Lymington Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girlguiding Hampshire West Unit Structure As at 16 April 2019 Division District Unit Chandlers Ford Division 10Th Chandlers Ford

Girlguiding Hampshire West Unit structure as at 16 April 2019 Division District Unit Chandlers Ford Division 10th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 14th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 14th Chandlers Ford Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Div Rgu Senior Section Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Ramalley Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Ramalley Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford West Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 2nd Chandlers Ford Ramalley (Formerly 2nd Chandlers Ford) Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 2nd Chandlers Ford Ramalley Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 2nd Chandlers Ford Ramalley Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 2nd Ramalley (Chandlers Ford) Senior Section Unit Chandlers Ford Division 3rd Chandlers Ford Ramalley Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford Ramalley Coy Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford S Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford Senior Section Unit Chandlers Ford Division 5th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 5th Chandlers Ford Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 6th Chandlers Ford Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 8th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 9th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit -

The Archaeology of Mining, and Quarrying, for Salt and the Evaporites (Gypsum, Anhydrite, Potash and Celestine)

The archaeology of mining, and quarrying, for Salt and the Evaporites (Gypsum, Anhydrite, Potash and Celestine) Test drafted by Peter Claughton Rock salt, or halite (NaCl- sodium chloride), has been mined since the late 17th century, having been discovered during exploratory shaft sinking for coal at Marbury near Northwich, Cheshire, in November 1670. Prior to that the brine springs of Cheshire and those at Droitwich in Worcestershire were the source of salt produced by evaporation, along with production from a large number of coastal sites using seawater. Alabaster, fine grained gypsum (CaSO4. 2H2O - hydrated calcium sulphate), has however been quarried in the East Midlands for use in sculpture since at least the 14th century (Cheetham 1984, 11-13) and the use of gypsum for making plaster dates from about the same period. Consumption The expansion of mining and quarrying for salt and the other evaporites came in the 19th century with the development of the chemical industry. Salt (sodium chloride) was a feedstock for the production of the chlorine used in many chemical processes and in the production of caustic soda (sodium hydroxide) and soda ash (sodium carbonate). Anhydrite (anhydrous calcium sulphate) was used in the production of sulphuric acid. Salt or halite (rock salt) was first mined at Winsford in Cheshire (the site of the only remaining active rock salt mine in England) in 1844. Production expanded in the late 19th century to feed the chemical industry in north Cheshire (together with increasing brine production from the Northwich salt fields). The Lancashire salt deposits, on the Wyre estuary at Fleetwood and Preesall, not discovered until 1872 whilst boring in search of haematite (Landless 1979, 38), were a key to the development of the chemical industry in that area. -

William Furmval, H. E. Falk and the Salt Chamber of Commerce, 1815-1889: "Ome Chapters in the Economic History of Cheshire

WILLIAM FURMVAL, H. E. FALK AND THE SALT CHAMBER OF COMMERCE, 1815-1889: "OME CHAPTERS IN THE ECONOMIC HISTORY OF CHESHIRE BY W. H. CHALONER, M.A., PH.D. Read 17 November 1960 N the second volume of his Economic History of Modern I Britain (p. 145), Sir John Clapham, writing of the chambers of commerce and trade associations which multiplied rapidly after 1860, suggested that between 1850 and 1875 "there was rather less co-operation among 'capitalist' producers than there had been in the more difficult first and second quarters" of the nineteenth century. He mentioned that in the British salt industry there had been price-fixing associations "based on a local monopoly" in the early nineteenth century, and added that after 1825 the industry "witnessed alternations of gentle men's agreements and 'fighting trade' " until the formation of the Salt Union in 1888. This combine has been called "the first British trust", but to the salt proprietors of the time it was merely "a new device, made easier by limited liability, for handling an old problem". (1) The purpose of this study is to examine in greater detail the business organisation of the natural local monopoly enjoyed by the Cheshire saltmakers in the nineteenth century and to trace the part played by "The Coalition" and the Salt Chamber of Commerce in fostering price regulation and output restriction between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and 1889.< 2 > 111 Op. cit., pp. 147-8; see also Accounts and Papers, 1817, III, 123, p. 22, and E. Hughes, Studies in Administration and Finance, 1558-1825 (1934), pp. -

Victorian Salt Pans and Rock Salt Mining

Victorian Salt Pans Cheshire became dominant in salt making because of its easy access to strong natural brine and rock salt and good communica- tions. But this came at a cost to the environ- ment until the change to controlled brine pumping and vacuum evaporation. Salt was skimmed into salt moulds - originally Salt blocks were sold complete, or crushed to Brine was pumped to a brine tank ready to be baskets, later cooper made cones, then make fine salt. gravity fed to the salt pans. wooden boxes. Images from AF Calvert – Salt in Cheshire, London, 1913 Lump Crushing Storage & Packing Trap doors Brine A fine pan described in the Illustrated London Drying Area News 1850. Fishery pans could be much Brine 200°F Flues and ditches larger and made coarser crystals in pans set Firing Area up outdoors to replicate ‘Bay Salt’. The surviving brine pump at Murgatroyd’s Pan House Stove House Salt Works, Middlewich. Open pan salt works made fine salt and block Flues carried heat and fumes from the salt in a Pan House with an attached Stove furnace underneath the Stove House to a Rock Salt Mining House. Coal was burnt under the iron pan. chimney. Rising heat dried the salt when it Refineries Rock salt itself was not found until 1670, Salt was skimmed into boxes and barrowed was ‘lofted’ to the warehouse floor above. ‘There was a growth in rock salt refineries when William Jackson discovered it into the Stove House. after 1670 but Acts of Parliament restricted whilst prospecting for coal. their construction. -

Hordle Lakes

HORDLE LAKES HORDLE, HAMPSHIRE A Highly Regarded Coarse Fishery Providing An Excellent Lifestyle & Business Opportunity With Further Potential, Situated In A Most Desirable Rural Location The lakes are heavily stocked with Carp, Tench, Perch, Bream, Roach, SITUATION Chubb & Rudd providing excellent sport which has enabled the LAKES fishery to become recognised nationally achieving regular coverage New Milton 1.3 miles, Lymington 5 miles, Brockenhurst 6.2 miles, Spring Lake Extending to 0.7 acres, Spring lake provides 20 pegs across various angling publications. Anglers Mail voted the site as Christchurch 8.8 miles, Cadnam (M27) 15.5 miles, Bourne- and holds Carp up to 24lbs along with Tench to 7lbs, Bream to one of the top 100 British Commercial Fisheries in 2010. mouth 15 miles 6lbs, Perch to 3lbs and Roach and Rudd. A number of islands offer Railway Stations: Brockenhurst to London/Waterloo 1h 36mins, good features with lily pads and rushes. New Milton to London/Waterloo 1h 44mins The spring fed lakes cater for day ticket anglers, fishing clubs who International Airports: Bournemouth International Airport hold regular matches and specimen anglers who can night fish 10 miles. Southampton 25 miles. subject to booking. Many of the lakes also enjoy easy disabled access from the carpark. Hordle Lakes is situated in the popular village of Hordle on the southern edge of The New Forest National Park and enjoys an The current owners supplement their income with tuition; tackle sales attractive rural setting with easy access from Ashley Road. The property and refreshments with scope to develop the business and property benefits from good communication links with the A31 & A35 to the further, subject to obtaining the necessary planning consents. -

Coastal Landfill and Shoreline Management: Implications for Coastal Adaptation Infrastructure

NERC Environmental Risk to Infrastructure Innovation Programme (ERIIP) Coastal Landfill and Shoreline Management: Implications for Coastal Adaptation Infrastructure Case Study: Pennington Prepared by: R.P. Beaven, A.S. Kebede, R.J. Nicholls, I.D. Haigh, J. Watts, A. Stringfellow This report was produced by the University of Southampton Waste Management Research Group and Energy and Climate Change Group as part of a study for the “Coastal landfill and shoreline management: implications for coastal adaptation infrastructure” project. This was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC: NE/N012909/1) as part of the Environmental Risks to Infrastructure Innovation Programme. Suggested citation: R.P. Beaven, R.J. Nicholls, I.D. Haigh, A.S. Kebede, J. Watts, A. Stringfellow, 2018. Coastal Landfill and Shoreline Management: Implications for Coastal Adaptation Infrastructure — Pennington Marshes Case Study. Report for Natural Environment Research Council. 37pp. Cover photograph, courtesy of Anne Stringfellow, University of Southampton. View of Pennington seawall (2018). 2 Table of Contents: Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6 2. Background ............................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Study -

Brockhampton Conservation Area Character Appraisal – (Rev A) April 2007

BROCKHAMPTON CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT- DEFINITION OF SPECIAL INTEREST OF THE CONSERVATION AREA (Executive Summary) 1. INTRODUCTION • Conservation Area Designation • Location and Setting • Historic Context 2. AREA DEFINITION • Entrances • Boundaries 3. CHARACTER AND APPEARANCE • Urban Form/Townscape • Buildings of Interest • Other Special Features 4. CONTROL OF DEVELOPMENT 5. NEXT STEPS • Recommendations for Future Management • Opportunities for Enhancement • Public Consultation • Management Plan and Monitoring SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT: - DEFINITION OF SPECIAL INTEREST OF THE BROCKHAMPTON CONSERVATION AREA 1. This is an Executive Summary of the key elements (of significance) that define the essential character and qualities of the Brockhamton Conservation Area, which was designated on 13 April 2005 – “the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance”. It aims to provide a succinct picture of the conservation area as it is today - defining its special qualities and heritage assets particularly in terms of the area’s local distinctiveness and special interest. These qualities should be safeguarded and where possible, enhanced. 2. Brockhampton Conservation Area is located just to the west of Havant town centre and primarily within the area defined by West Street in the north, Brockhampton Road to the west and Brockhampton Lane in the east. West Street is known to mark the historic Roman route from Chichester to Wickham and the earliest remaining buildings along this road are statutorily listed. 3. To the south of West Street, the natural springs, streams, collecting basins, lakes and surrounding land lie at the heart of the area and are one of the reasons for the presence of the Portsmouth Water Company. -

Salt Deposits in the UK

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by NERC Open Research Archive Halite karst geohazards (natural and man-made) in the United Kingdom ANTHONY H. COOPER British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG, Great Britain COPYRIGHT © BGS/NERC e-mail [email protected] +44 (-0)115 936 3393 +44 (-0)115 936 3475 COOPER, A.H. 2002. Halite karst geohazards (natural and man-made) in the United Kingdom. Environmental Geology, Vol. 42, 505-512. This work is based on a paper presented to the 8th Multidisciplinary Conference on Sinkholes and the Engineering and Environmental impact of karst, Louisville, Kentucky, April 2001. In the United Kingdom Permian and Triassic halite (rock salt) deposits have been affected by natural and artificial dissolution producing karstic landforms and subsidence. Brine springs from the Triassic salt have been exploited since Roman times, or possibly earlier, indicating prolonged natural dissolution. Medieval salt extraction in England is indicated by the of place names ending in “wich” indicating brine spring exploitation at Northwich, Middlewich, Nantwich and Droitwich. Later, Victorian brine extraction in these areas accentuated salt karst development causing severe subsidence problems that remain a legacy. The salt was also mined, but the mines flooded and consequent brine extraction caused the workings to collapse, resulting in catastrophic surface subsidence. Legislation was enacted to pay for the damage and a levy is still charged for salt extraction. Some salt mines are still collapsing and the re-establishment of the post-brine extraction hydrogeological regimes means that salt springs may again flow causing further dissolution and potential collapse. -

3 New Grade a Industrial / Warehouse Units 25,626 - 101,726 Sq Ft Available to Let Q4 2018

3 NEW GRADE A INDUSTRIAL / WAREHOUSE UNITS 25,626 - 101,726 SQ FT AVAILABLE TO LET Q4 2018 STANBRIDGE ROAD, HAVANT, HAMPSHIRE PO9 2NS A development by: VELOCITYHAVANT.COM PORTSMOUTH CHICHESTER M27 SOUTHAMPTON A3(M) A27 HAVANT TOWN CENTRE HAVANT RAIL STATION DELONGHI CROSSLAND DRIVE FLEXIBLE UNIT SIZES GRADE A QUALITY SPACE EXCELLENT TRANSPORT LINKS STANBRIDGE ROAD NEW LANE FASTER FORWARD A new high specification industrial / distribution BARTONS ROAD development providing flexible unit sizes from 25,626 to 101,726 sq ft, located in one of the South Coast’s most established industrial locations. Providing excellent communications to the A27, M27 and A3(M) corridors, and within walking distance of Havant town centre and railway station, Velocity provides an excellent opportunity for new premium space. LOCATION Velocity benefits from being in a strategic location, just 1 mile from Havant town centre and mainline railway station, providing direct trains to London Waterloo, Portsmouth, Brighton and Southampton. The A27 / M27 road network is within approximately 1.5 miles and the A3(M) is approximately 2 miles, providing fast access to Portsmouth (8 miles) and Southampton (26 miles) to the west, and London (69 miles) to the north. Major occupiers in the vicinity include; Pfizer, Kenwood Delonghi, Eaton Industrial Hydraulics, Formaplex, Dunham-Bush and Colt. Computer Generated Image 12 CYCLES REFUSE 12 CYCLES 34.6M 34.6M 46M REFUSE REFUSE 20 CYCLES 1ST FLOOR OFFICE 1ST FLOOR OFFICE 1ST FLOOR OFFICE UNIT 1 UNIT 2 UNIT 3 STANBRIDGE ROAD RAPID DELIVERY ACCOMMODATION Available for occupation Q4 2018, the units UNIT 1 offer a flexible range of accommodation from WAREHOUSE 22,462 sq ft 2,086 sq m 25,626 - 101,726 sq ft on a site extending to approximately 5 acres. -

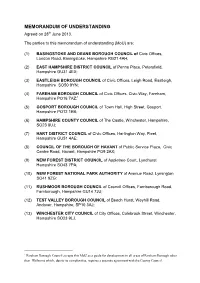

Memorandum of Understanding 2013

MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING Agreed on 28th June 2013. The parties to this memorandum of understanding (MoU) are: (1) BASINGSTOKE AND DEANE BOROUGH COUNCIL of Civic Offices, London Road, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 4AH; (2) EAST HAMPSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL of Penns Place, Petersfield, Hampshire GU31 4EX; (3) EASTLEIGH BOROUGH COUNCIL of Civic Offices, Leigh Road, Eastleigh, Hampshire SO50 9YN; (4) FAREHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL of Civic Offices, Civic Way, Fareham, Hampshire PO16 7AZ;1 (5) GOSPORT BOROUGH COUNCIL of Town Hall, High Street, Gosport, Hampshire PO12 1EB; (6) HAMPSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL of The Castle, Winchester, Hampshire, SO23 8UJ; (7) HART DISTRICT COUNCIL of Civic Offices, Harlington Way, Fleet, Hampshire GU51 4AE; (8) COUNCIL OF THE BOROUGH OF HAVANT of Public Service Plaza, Civic Centre Road, Havant, Hampshire PO9 2AX; (9) NEW FOREST DISTRICT COUNCIL of Appletree Court, Lyndhurst Hampshire SO43 7PA; (10) NEW FOREST NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY of Avenue Road, Lymington SO41 9ZG: (11) RUSHMOOR BOROUGH COUNCIL of Council Offices, Farnborough Road, Farnborough, Hampshire GU14 7JU; (12) TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL of Beech Hurst, Weyhill Road, Andover, Hampshire, SP10 3AJ; (13) WINCHESTER CITY COUNCIL of City Offices, Colebrook Street, Winchester, Hampshire SO23 9LJ. 1 Fareham Borough Council accepts this MoU as a guide for development in all areas of Fareham Borough other than Welborne which, due to its complexities, requires a separate agreement with the County Council. CONTENTS CLAUSE 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................. -

Solent Grange, New Lane, Milford-On-Sea, Hampshire, So41 0Uq

www.haywardfox.co.uk SEA - ON - MILFORD GREEN, VILLAGE THE SOLENT GRANGE, NEW LANE, MILFORD-ON-SEA, MILFORD COURT, NEW LANE, MILFORD-ON-SEA, HAMPSHIRE SO41 0UQ HAMPSHIRE SO41 0UG Please note the photographs shown above were taken at other Royale development Example: THE AVANTI Example: THE CANFORD EXAMPLES OF LAYOUTS - OTHER STYLES AVAILABLE For more information on this property or to arrange an accompanied viewing, please contact: 01590 644933 or [email protected] Our offices are located in: Bransgore ~ 01425 673707 Brockenhurst ~ 01590 624300 Lymington ~ 01590 675424 Mayfair ~ 020 7079 1454 Milford on Sea ~ 01590 644933 New Milton ~ 01425 638656 Sway ~ 01590 681656 www.haywardfox.co.uk 9 High Street Milford on Sea Lymington Hampshire SO41 0QF Tel: 01590 644933 Fax: 01590 641836 Email: [email protected] SOLENT GRANGE, NEW LANE, MILFORD-ON-SEA, HAMPSHIRE SO41 0UQ PRICES FROM: £250,000 AN EXCITING BRAND NEW, GATED, FULLY RESIDENTIAL DETACHED LUXURY BUNGALOW DEVELOPMENT FOR THE OVER 45'S, IN 'TURN-KEY' CONDITION, FULLY FURNISHED, READY FOR IMMEDIATE OCCUPATION, WELL LOCATED A SHORT DISTANCE FROM THE VILLAGE CENTRE OF MILFORD-ON-SEA, ADJACENT TO STURT POND & KEYHAVEN NATURE RESERVE Spacious accommodation provided in a variety of styles depending on the size and model of each property, but primarily offering a sitting room, dining room, fully fitted kitchen, two double bedrooms, master bedroom with en-suite, bathroom, double glazing, gfch, parking and garden Appointments must be made via the Vendors Agents Hayward Fox SOLENT GRANGE, NEW LANE, MILFORD-ON-SEA, HAMPSHIRE, SO41 0UQ SOLENT GRANGE - This brand new development of fully residential luxury bungalows is set within a gated community, providing accommodation specifically for the over 45's. -

Hurst Spit to Lymington Project Introductory Briefing Note

Final June 2020 Hurst Spit to Lymington Project Introductory Briefing Note Introduction The Environment Agency in partnership with New Forest District Council, Hampshire County Council and Natural England with expert support from JBA Consulting are exploring a sustainable future for the coastal frontage between Hurst Spit and Lymington in relation to flood and coastal erosion risk management. This project aims to investigate if and how to respond to the significant challenges facing this area of coastline now and into the future, and how to fund any potential works going forward. This Briefing sets out more details, and we welcome your questions and input as the project develops. This coastal frontage is located within the New Forest and extends from Milford-on- Sea in the west, encompasses Keyhaven and Pennington Marshes extending up the Lymington River to the east (see Figure 1). The Hurst Spit to Lymington coastline is characterised by large areas of low-lying coastal habitats, including mudflats, saltmarsh and vegetated shingle. The existing defences, as well as protecting local communities, protects large areas of coastal grazing marsh and coastal lagoons. The habitats and the species which can be found along this section of coast are of international importance. The rich biodiversity creates the stunning landscape, which is accompanied by cultural and historical heritage of significant status. For these reasons the area attracts substantial visitor numbers and is enjoyed by a range of recreational users, for activities such as walking, sailing and fishing. These factors along with natural coastal processes will need to be carefully considered as the project develops.