By JOE BEN WHEAT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3 – State of the Bay, Third Edition

CHAPTER 3 – STATE OF THE BAY, THIRD EDITION The Human Role: Past Written by Alecya Gallaway At sundown we reached Redfish Bar, composed almost entirely of shells which extend from bank to bank the distance of several miles and appear to be formed by the confluence of the tide and the waters of the San Jacinto and Trinity, which unite a short distance above … This point is undoubtedly the head of navigation for vessels of heavy burden and has occurred to some as a more suitable site for a city than Galveston itself. —Texas in 1837, edited by Andrew Forest Muir (1958) Introduction This chapter examines the history of resource use in Galveston Bay and its adjacent land area. The chapter begins with a look back to the Pleistocene Ice Age and the impact of the earliest humans, continues with the use of resources by Native Americans and changes engendered by the transition to European-American settlement, and then focuses on the alterations that occurred to the bay as the regional focus shifted from agriculture to municipal and industrial development. This chapter describes resource use and human impact from pre-history to 1950. More recent developments and impacts are covered in Chapter 4. Resource Use: Prehistory to 1800 Galveston Bay is a recent feature of the Earth by geological reckoning. Thousands of years before the bay formed, water was held in continental ice sheets causing the sea level to be considerably lower than it is today. The shoreline was located 50–100 miles farther south into the area now covered by the Gulf of Mexico. -

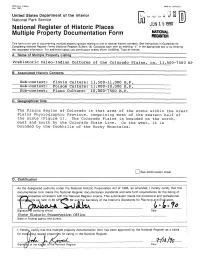

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB .vo ion-0018 (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUH151990' Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing___________________________________________ Prehistoric Paleo-Indian Cultures of the Colorado Plains, ca. 11,500-7500 BP B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ Sub-context; Clovis Culture; 11,500-11,000 B.P.____________ sub-context: Folsom Culture; 11,000-10,000 B.P. Sub-context; Piano Culture: 10,000-7500 B.P. C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ The Plains Region of Colorado is that area of the state within the Great Plains Physiographic Province, comprising most of the eastern half of the state (Figure 1). The Colorado Plains is bounded on the north, east and south by the Colorado State Line. On the west, it is bounded by the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. [_]See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of relaje«kproperties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional renuirifiaejits set forth in 36 CFSKPaV 60 and. -

Speakers and Presentations for 2018 Culturefest

Speakers and Presentations for 2018 CultureFest Thursday, Haynie Dig Site Tours Tour the current Crow Canyon dig site with our field archaeologists. Learn how our discoveries in the field are shedding new light on the importance of the Northern Chaco Outliers Project. Tours are scheduled for Thursday afternoon, October 11, leaving from the Crow Canyon campus and the Holiday Inn Express. Cost: $25 Friday, 9:30 – 10:30 Discover the inner workings of an archaeology lab and learn how lab archaeologists uncover the stories that lie behind artifacts. Leigh Cominiello, Crow Canyon’s Laboratory Education Coordinator, will discuss techniques used by lab archaeologists to clean, analyze, sort and catalog the thousands of artifacts found at Crow Canyon’s dig sites. Friday, 9:30 – 10:30 Will Tsosie, a Navajo storyteller and Tribal Archaeologist for the Navajo Nation, will present a lecture entitled Mountains of the New People: Cultural Landscape of the Navajo Nation. Will has served as scholar and educator for the College Field School and Crow Canyon CE trips. Friday and Saturday, 10:45 – 11:45 Louie Garcia (Tiwa/Piro) founded the New Mexico Pueblo Fiber Arts Guild in 2009. He teaches Pueblo weaving at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque. Louie will present two demonstrations – on the dyeing and spinning of traditional fibers and on Pueblo weaving techniques and design. Friday, 10:45 – 11:45 Grant Coffey is a GIS Archaeologist with Crow Canyon. In 2016, he used a drone to evaluate the cultural and natural features surrounding the Haynie site. This information helped Crow Canyon archaeologists plan their multi-year excavation program. -

Thesis Methods of Dating Glass Beads From

THESIS METHODS OF DATING GLASS BEADS FROM PROTOHISTORIC SITES IN THE SOUTH PLATTE RIVER BASIN, COLORADO Submitted by Christopher R. von Wedell Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2011 Master‟s Committee Advisor: Jason M. LaBelle Sammy J. Zahran Mary Van Buren ABSTRACT METHODS OF DATING GLASS BEADS FROM PROTOHISTORIC SITES IN THE SOUTH PLATTE RIVER BASIN, COLORADO Morphological characteristics and chemical trace elements counts acquired using Laser Ablation-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry analyses were documented for glass trade beads from 24 protohistoric archaeological assemblages in the South Platte River Basin. The resulting database was used to provide quantitative descriptions of each recorded assemblage and to characterize the types of glass beads currently reported in the region. Statistical analyses were then conducted to determine if and to what extent morphological and chemical traits change through time. Characteristics of beads in dated contexts were then used to develop a linear regression model in an attempt to determine if it is possible to estimate the age of beads from undated contexts. It is concluded that morphological and chemical characteristics of glass beads in dated contexts can be used to estimate the age of glass beads in undated contexts using linear regression. The results of this thesis demonstrate that morphological characteristics are currently more accurate and precise than chemistry although both methods hold potential for revision and improvement as more dated sites become available to supplement the statistical models. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was made possible by the encouragement, support, and gentle nudging of many individuals and institutions. -

Everything Will Be Changed: the Horse and the Comanche Empire

Everything Will Be Changed: The Horse and the Comanche Empire Stephen Kwas Senior Division Historical Paper Word Count: 2474 “Remember this: if you have horses everything will be changed for you forever.”1 - Attributed to Maheo, Creator God of the Cheyenne Bones of over 1,000 horses lay bleaching under a hot Texas sun, months-old remnants from the last stand of one of the greatest equestrian powers in history: the Comanche. Spanish horses allowed for the Comanche and other tribes of the Great Plains, who had lacked horses for over 15,000 years, to transform their societies. Upon its arrival, the Comanche immediately capitalized on the horse and used it to break the barrier of human physiology—the limits of human endurance which significantly restricted hunting, raiding, and trading—and created a vast trade empire. Many have romanticized this history by arguing that the horse was beneficial to all Comanches.2 This paper, however, argues that the horse brought wealth and power to some Comanches, but also brought slave markets, marginalization of women, constant warfare, and social stratification to their society. The tragic irony was that the horse, the very technology that allowed them to conquer their environment, eventually destroyed the ecological balance of the Plains and made them vulnerable to American invasions. Pedestrianism: Life before the Horse Before European contact, Plains Indians relied on farming as much as hunting and often oscillated between the two.3 Although the bison served as their main source of food, Plains 1 Alice Marriott and Carol K. Rachlin, Plains Indian Mythology (New York, NY: Meridian, 1975), 96. -

Charles C. Di Peso, 1920-1982

MEMORIALS Charles C. Di Peso, 19204982 Charles C. Di Peso died of cancer on 20 November 1982, at the Tucson Medical Center. Di Peso served for 30 years as Director of the Amerind Foundation, a non-profit research center in Dragoon, Arizona, devoted to the study of Native American culture history. His work on the prehistoric and early historic peoples of southern Arizona and northern Mexico is well known and respected. Di Peso belonged to many professional organizations, including the Society for Historical Archaeology, of which he was a founding member. His participation in the Society and in the profession will be greatly missed. Di Peso was born on 20 October 1920, in St. Louis, Missouri to Charles Corradino and Emma Klein Di Peso and grew up in Chicago Heights, Illinois. While still in high school, Di Peso was invited by Paul S. Martin of the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History to participate in an archaeological project in Colorado. The experience confirmed an interest in archaeology, which he pursued at Beloit College, working as a student assistant under Paul S. Nesbitt, director of Beloit’s Logan Museum. In 1941 Di Peso again joined Paul Martin on a Field Museum expedi- tion, this time the Pine Lawn, New Mexico, project. Di Peso graduated from Beloit in 1942 with a B.A. in Anthropology and a B.S. in Geology, and in June he married Frances Teague. From 1942 to 1946 Di Peso served in the United States Air Force as a First Lieutenant, Pilot, and Instructor in Advanced Training Course and Instru- ment Flying. -

Iuc5 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY

uuO I iuc5G NO. 1US GRADUATE STUDIES TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY The Panhandle Aspect of the Chaquaqua Plateau Robert G. Campbell i II No. 11 March 1976 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Grover E. Murray, President Glenn E. Barnett, Executive Vice President Regents.-Clint Formby (Chairman), J. Fred Bucy, Jr., Bill E. Collins, John J. Hinchey, A. J. Kemp, Jr., Robert L. Pfluger, Charles G. Scruggs, Judson F. Williams, and Don R. Workman. l'olic C mmiiiiicc.--J. Knox Jones,Academic Jr. (Chairman. Pidlicatio Dilford C. P Carter (Executive Director), C. Leonard Ainsworth, Frank B. Conselman, Samuel F. Curl. Hugh H. Genoways, Ray C. Janeway, William R. Johnson, S. M. Kennedy, Thomas A. Langford. George F. Meenaghan, Harley D. Oberhclman, Robert L. Packard, and Charles W. Sargent. Graduate Studies No. 11 118 pp. 5 March 1976 $3.00 Graduate Studies are numbered separately and published on an irregular basis under the auspices of the Dean of the Graduate School and Director of Academic Publications, and in cooperation with the International Center for Arid and Semi-Arid Land Studies. Copies may be obtained on an exchange basis from, or purchased through, the Exchange Librarian, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409. V Texas Tech Press, Lubbock. Texas 1976 GRADUATE STUDIES TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY The Panhandle Aspect of the Chaquaqua Plateau Robert G. Campbell No. 11 March 1976 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Grover E. Murray, President Glenn E. Barnett, Executive Vice President Regents.-Clint Formby (Chairman), J. Fred Bucy, Jr., Bill E. Collins, John J. Hinchey, A. J. Kemp, Jr., Robert L. Pfluger, Charles G. Scruggs, Judson F. -

American Tri-Racials

DISSERTATIONEN DER LMU 43 RENATE BARTL American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America We People: Multi-Ethnic Indigenous Nations and Multi- Ethnic Groups Claiming Indian Ancestry in the Eastern United States Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Renate Bartl aus Mainburg 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Berndt Ostendorf Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Eveline Dürr Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 26.02.2018 Renate Bartl American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America Dissertationen der LMU München Band 43 American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America by Renate Bartl Herausgegeben von der Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1 80539 München Mit Open Publishing LMU unterstützt die Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München alle Wissenschaft ler innen und Wissenschaftler der LMU dabei, ihre Forschungsergebnisse parallel gedruckt und digital zu veröfentlichen. Text © Renate Bartl 2020 Erstveröfentlichung 2021 Zugleich Dissertation der LMU München 2017 Bibliografsche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografe; detaillierte bibliografsche Daten sind im Internet abrufbar über http://dnb.dnb.de Herstellung über: readbox unipress in der readbox publishing GmbH Rheinische Str. 171 44147 Dortmund http://unipress.readbox.net Open-Access-Version dieser Publikation verfügbar unter: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-268747 978-3-95925-170-9 (Druckausgabe) 978-3-95925-171-6 (elektronische Version) Contents List of Maps ........................................................................................................ -

An Archaeological Survey for the Ed Kharbat Drive Extension, Phase Ii Project in Montgomery County, Texas

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR THE ED KHARBAT DRIVE EXTENSION, PHASE II PROJECT IN MONTGOMERY COUNTY, TEXAS Antiquities Permit 4733 By William E. Moore Brazos Valley Research Associates Contract Report Number 185 2008 AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR THE ED KHARBAT DRIVE EXTENSION, PHASE II PROJECT IN MONTGOMERY COUNTY, TEXAS Project Number: BVRA 07-34 Principal Investigator William E. Moore Prepared by Brazos Valley Research Associates 813 Beck Street Bryan, Texas 77803 Prepared for City of Conroe Post Office Box 3066 Conroe, Texas 77305 ABSTRACT An archaeological survey was conducted along the route of the proposed Ed Kharbat Drive extension in the city limits of Conroe in central Montgomery County, Texas by Brazos Valley Research Associates (BVRA) on December 4, 2007 for the City of Conroe under Antiquities Permit 4733. No archaeological sites were identified, and no artifacts were collected. In all, 4560 feet (12.6 acres) were investigated. It is recommended that construction be allowed to proceed as planned. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I appreciate the assistance of those who participated in this project. Maps and logistical support were provided by Troy Toland, P.E. of the Capital Division, City of Conroe. I was assisted in the field by C. J. Locklear and Tanner Singleton. Jean Hughes at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory (TARL) checked the site records for previously recorded archaeological sites in the project area and vicinity. Lili G. Lyddon prepared the cover and figures that appear in this report. Nora Rogers assisted in the editing -

Introduction to the Earl Morris Papers Joe Ben Wheat University of Colorado, Boulder

University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Series in Anthropology Anthropology 6-1963 No. 8: Introduction to the Earl Morris Papers Joe Ben Wheat University of Colorado, Boulder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/santhro Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Wheat, Joe Ben, "No. 8: Introduction to the Earl Morris Papers" (1963). Series in Anthropology. 18. http://scholar.colorado.edu/santhro/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Anthropology at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Series in Anthropology by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BASKET MAKER III SITES NEAR DURANGO, COLORADO BY ROY L. CARLSON R e s e a r c h A ss o c ia t e in A nthropology U n iv e r s it y of C o l o r a d o M u s e u m w it h INTRODUCTION TO THE EARL MORRIS PAPERS BY JOE BEN WHEAT C u r a t o r of A nthropology U n iv e r s it y of C o l o r a d o M u s e u m U n iver sity of C olorado P ress Series in Anthropology, No. 8 The Earl Morris Papers, No. I University of Colorado Press Boulder, Colorado, June, 1963 Price $3.50 INTRODUCTION TO THE EARL MORRIS PAPERS For nearly half a century Earl H. Morris was one of the nation’s leading archaelogists. -

5MT3 Site Report

Site 5MT3: A Small Village in the Joe Ben Wheat Site Complex (5MT16722), Yellow Jacket, Colorado Richard H. Wilshusen and Jeannette L. Mobley-Tanaka 2005 Chapter 1 Introduction to the Archaeology of 5MT3 Richard H. Wilshusen and Jeannette L. Mobley-Tanaka Site 5MT3 is one of three sites in the Joe Ben Wheat Site Complex (5MT16722), which was listed to the National Register of Historic Places in 2004 (Lekson 2004). Site 5MT3 has three distinct periods of occupation, which fall within the Basketmaker III, Pueblo II, and Pueblo III periods in the Pecos classification. These occupations date to approximately A.D. 630–660, 1050–1150, and 1150–1275. Although 5MT3 was the second site to be investigated, it was the site that Joe Ben Wheat returned to again and again over a 30-year period of time. There have been several theses and dissertations—as well as various journal articles—that have focused on aspects or artifacts from the site; but there still is the need for a detailed site report. The present report is a preliminary site report that introduces researchers to the research history, archaeological setting, and occupation history of the site. A full site report would require hundreds of pages of descriptive text and at least a preliminary analysis of the artifacts. This is not possible at the present, but we anticipate that this preliminary report will encourage the research necessary to produce a more comprehensive site report. The Pueblo III occupation (5MT3. Figure 1) at the site is the largest and most well revealed of the three occupations. -

AN EXAMINATION of LATE PUEBLO II and PUEBLO III TOWERS in the NORTHERN SAN JUAN REGION by ALISON VANESSA BREDTHAUER

A TOWERING ENIGMA: AN EXAMINATION OF LATE PUEBLO II AND PUEBLO III TOWERS IN THE NORTHERN SAN JUAN REGION by ALISON VANESSA BREDTHAUER A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Art Department of Anthropology 2010 ! ""! This thesis entitled: A Towering Enigma: An Examination of Pueblo II and Pueblo III Towers in the Northern San Juan Region written by Alison Vanessa Bredthauer has been approved for the Department of Anthropology _____________________________________ Dr. Catherine Cameron _____________________________________ Dr. Stephen Lekson _____________________________________ Dr. Donna Glowacki (Notre Dame University) Date __________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ! """! Abstract Bredthauer, Alison Vanessa (M.A., Anthropology) A Towering Enigma: An Examination of Late Pueblo II and Pueblo III Period towers in the northern San Juan region Thesis directed by Dr. Catherine M. Cameron One of the most impressive structural elements of ancestral Puebloan culture is the masonry tower, a structure most commonly found during the Pueblo III (A.D. 1150-1300) period of northern San Juan region occupation. This time period was associated with dramatic and significant social changes that characterized the decades before the ultimate depopulation of the region in the 1300s. The following thesis research explores both the variability in construction and context of towers in order to better understand how they functioned during this time period.