Autistic Sociality 69

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhythm and Timing in Autism: Learning to Dance

REVIEW ARTICLE published: 19 April 2013 INTEGRATIVE NEUROSCIENCE doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00027 Rhythm and timing in autism: learning to dance Pat Amos* Training and Private Consultation, Ardmore, PA, USA Edited by: In recent years, a significant body of research has focused on challenges to neural Anne M. Donnellan, University of connectivity as a key to understanding autism. In contrast to attempts to identify a Wisconsin-Madison, University of single static, primarily brain-based deficit, children and adults diagnosed with autism are San Diego, USA increasingly perceived as out of sync with their internal and external environments in Reviewed by: Elizabeth B. Torres, Rutgers dynamic ways that must also involve operations of the peripheral nervous systems. The University, USA noisiness that seems to occur in both directions of neural flow may help explain challenges Trevor McDonald, Education to movement and sensing, and ultimately to entrainment with circadian rhythms and social Associates Inc., USA interactions across the autism spectrum, profound differences in the rhythm and timing of *Correspondence: movement have been tracked to infancy. Difficulties with self-synchrony inhibit praxis, and Pat Amos, 635 Ardmore Avenue, Ardmore, PA 19003-1831, USA. can disrupt the “dance of relationship” through which caregiver and child build meaning. e-mail: [email protected] Different sensory aspects of a situation may fail to match up; ultimately, intentions and actions themselves may be uncoupled. This uncoupling may help explain the expressions of alienation from the actions of one’s body which recur in the autobiographical autism literature. Multi-modal/cross-modal coordination of different types of sensory information into coherent events may be difficult to achieve because amodal properties (e.g., rhythm and tempo) that help unite perceptions are unreliable. -

Educational Inclusion for Children with Autism in Palestine. What Opportunities Can Be Found to Develop Inclusive Educational Pr

EDUCATIONAL INCLUSION FOR CHILDREN WITH AUTISM IN PALESTINE. What opportunities can be found to develop inclusive educational practice and provision for children with autism in Palestine; with special reference to the developing practice in two educational settings? by ELAINE ASHBEE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Education University of Birmingham November 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Amendments to names used in thesis The Amira Basma Centre is now known as Jerusalem Princess Basma Centre Friends Girls School is now known as Ramallah Friends Lower School ABSTRACT This study investigates inclusive educational understandings, provision and practice for children with autism in Palestine, using a qualitative, case study approach and a dimension of action research together with participants from two educational settings. In addition, data about the wider context was obtained through interviews, visits, observations and focus group discussions. Despite the extraordinarily difficult context, education was found to be highly valued and Palestinian educators, parents and decision–makers had achieved impressive progress. The research found that autism is an emerging field of interest with a widespread desire for better understanding. -

Autism Speaks Does Not Provide Medical Or Legal Advice Or Services

100 Day Kit A tool kit to assist families in getting the critical information they need in the first 100 days after an autism diagnosis. Autism Speaks does not provide medical or legal advice or services. Rather, Autism Speaks provides general information about autism as a service to the community. The information provided in this kit is not a recommendation, referral or endorsement of any resource, therapeutic method, or service provider and does not replace the advice of medical, legal or educational professionals. This kit is not intended as a tool for verifying the credentials, qualifications, or abilities of any organization, product or professional. Autism Speaks has not validated and is not responsible for any information or services provided by third parties. You are urged to use independent judgment and request references when considering any resource associated with the provision of services related to autism ©2013 Autism Speaks Inc. Autism Speaks and Autism Speaks It’s Time To Listen & Design are trademarks owned by Autism Speaks Inc. All rights reserved. About this Kit Autism Speaks would like to extend special thanks to the Parent Advisory Committee for the time and effort that they put into reviewing the 100 Day Kit. 100 Day Kit Parent Advisory Committee Stacy Crowe Rodney Goodman Beth Hawes Deborah Hilibrand Dawn Itzkowitz Stacy Karger Marjorie Madfis Donna Ross- Jones Judith Ursitti Marcy Wenning Family Services Committee Members Dan Aronson Parent Liz Bell Parent Sallie Bernard Parent, Executive Director, SafeMinds Farah Chapes Chief Administrative Officer, The Marcus Autism Center Peter F. Gerhardt, Ed.D Director, Upper School, The McCarton School Founding Chair of the Scientific Council, Organization for Autism Research Lorrie Henderson Ph.D., LCSW, MBA Brian Kelly * ** Parent ©2013 Autism Speaks Inc. -

Tapemaster Main Copy

Jeff Schechtman Interviews December 1995 to January 2018 2018 Daniel Pink When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing 1/18/18 Martin Shiel WhoWhatWhy Story on Deutsche Bank 1/17/18 Sara Zaske Achtung Baby: An American Mom on the German Art of Raising Self-Reliant Children 1/17/18 Frances Moore Lappe Daring Democracy: Igniting Power, Meaning and Connection for the America We Want 1/16/18 Martin Puchner The Written Word: The Power of Stories to Shape People, History, Civilization 1/11/18 Sarah Kendzior Author /Journalist “The View From Flyover Country” 1/11/18 Gordon Whitman Stand Up! How to Get Involved, Speak Out and Win in a World on Fire 1/10/18 Brian Dear The Friendly Orange Glow: The Untold Story of the PLATO System and the Dawn of Cyberculture 1/9/18 Valter Longo The Longevity Diet: The New Science behind Stem Cell Activation 1/9/18 Richard Haass The World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order 1/8/18 Chloe Benjamin The Immortalists: A Novel 1/5/18 2017 Morgan Simon Real Impact: The New Economics of Social Change 12/20/17 Daniel Ellsberg The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a War Planner 12/19/17 Tom Kochan Shaping the Future of Work: A Handbook for Action and a New Social Contract 12/15/17 David Patrikarakos War in 140 Characters: How Social Media is Reshaping Conflict in the Twenty First Century 12/14/17 Gary Taubes The Case Against Sugar 12/13/17 Luke Harding Collusion: Secret Meetins, Dirty Money and How Russia Helped Donald Trump Win 12/13/17 Jake Bernstein Secrecy World: Inside the Panama Papers -

An Ethico-Aesthetics of Imagination

Racing Toward Uncertainty: an Ethico-Aesthetics of Imagination Jack Kahn Pomona College: Claremont, California Abstract In this paper, I examine imagination as a performative expression using an ethico-aesthetic paradigm (which I take from Baruch Spinoza and Félix Guattari) which accounts for the ways, affects, as ethical orientations toward the world, participate in creative world-making amidst conditions of social and political entrapment. Using William James’ notion of “medical materialism” as a critical tool, I turn to the work and life of South Asian autistic poet Tito Mukhopadhyay to trouble the ways critical discourse understands ‘autism’. These are namely as a signifier for particular reductive perceptuo-aesthetic relations (an understanding I find in the work of Erin Manning), in order to re-conceive how disability politics might resist and restructure totalizing systems of global domination without referring to rights or identity claims. Keywords/Terms Disability, autism, ethico-aesthetics, affect, world-making, imagination, medical materialism, embodiment, perception, neuro-reductionism, performativity, entrapment, crisis Correspondence information: [email protected] Introduction: On Autism and Ethico-Aesthetics Discourse frequently describes autism as an “enigma.” But what would it mean for one to live within enigma, for one’s body to be cast as a riddle, a puzzle, a question? To think through autism would compel not simply an analysis of its construction within discourse, but an analysis of what it means to be immersed within and to respond to the realities and entrapments created by the interactions between the cultural and the embodied. That which “autism” signifies exceeds its definition by diagnostic criteria, which comprehends autistic difference as a pervasive social and developmental pathology that disables those who embody it. -

The Interviews

Jeff Schechtman Interviews December 1995 to April 2017 2017 Marcus du Soutay 4/10/17 Mark Zupan Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest 4/6/17 Johnathan Letham More Alive and Less Lonely: On Books and Writers 4/6/17 Ali Almossawi Bad Choices: How Algorithms Can Help You Think Smarter and Live Happier 4/5/17 Steven Vladick Prof. of Law at UT Austin 3/31/17 Nick Middleton An Atals of Countries that Don’t Exist 3/30/16 Hope Jahren Lab Girl 3/28/17 Mary Otto Theeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality and the Struggle for Oral Health 3/28/17 Lawrence Weschler Waves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the Astrophysicists 3/28/17 Mark Olshaker Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs 3/24/17 Geoffrey Stone Sex and Constitution 3/24/17 Bill Hayes Insomniac City: New York, Oliver and Me 3/21/17 Basharat Peer A Question of Order: India, Turkey and the Return of the Strongmen 3/21/17 Cass Sunstein #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media 3/17/17 Glenn Frankel High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic 3/15/17 Sloman & Fernbach The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Think Alone 3/15/17 Subir Chowdhury The Difference: When Good Enough Isn’t Enough 3/14/17 Peter Moskowitz How To Kill A City: Gentrification, Inequality and the Fight for the Neighborhood 3/14/17 Bruce Cannon Gibney A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America 3/10/17 Pam Jenoff The Orphan's Tale: A Novel 3/10/17 L.A. -

Transcript for the IACC Full Committee Meeting on July 9, 2013

1 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES INTERAGENCY AUTISM COORDINATING COMMITTEE FULL COMMITTEE MEETING TUESDAY, JULY 9, 2013 The Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC) met in Room 10, Sixth Floor, C Wing, Building 31, 31 Center Drive, Bethesda, Maryland, from 9:09 a.m. until 5:28 p.m., Thomas Insel, Chair, presiding. PRESENT: THOMAS INSEL, M.D., Chair, IACC, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) SUSAN DANIELS, Ph.D., Executive Secretary, IACC, NIMH IDIL ABDULL, Somali American Autism Foundation JAMES BALL, Ed.D., BCBA-D, JB Autism Consulting and Autism Society of America (attended by phone) ANSHU BATRA, M.D., Our Special Kids JAMES BATTEY, M.D., Ph.D., National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) 2 PRESENT (continued): LINDA BIRNBAUM, Ph.D., National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (attended by phone) COLEEN BOYLE, Ph.D., M.S.Hyg., U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) JOSEPHINE BRIGGS, M.D., National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) SALLY BURTON-HOYLE, Ed.D., Eastern Michigan University MATTHEW CAREY, Ph.D., Left Brain Right Brain (attended by phone) JAN CRANDY, Nevada State Autism Treatment Assistance Program and Nevada Commission on Autism Spectrum Disorders GERALDINE DAWSON, Ph.D., Duke University DENISE DOUGHERTY, Ph.D., Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) TIFFANY FARCHIONE, M.D., U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ALAN GUTTMACHER, M.D., Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) LAURA KAVANAGH, M.P.P., Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) DONNA KIMBARK, Ph.D., U.S. -

The Informative Pointing Method

THE INFORMATIVE POINTING METHOD By Portia Iversen strangeson.com THE INFORMATIVE POINTING METHOD November 11, 2007 INTRODUCTION A joint attention and literacy-based approach to convey in this manual. Some of these core elements communication for individuals with autism overlap with other methods such as the Rapid Prompting Method, Facilitated Communication, Mar- The Informative Pointing Method and ion Blank’s Light on Literacy program, Greenspan’s this manual came about after my book Floortime approach, Relationship Development In- Strange Son was published in January tervention and even the Applied Behavioral Analysis 2007. Many people contacted me after model. my book came out, wanting to know how they could get their nonverbal au- It is my hope that the online Community tistic child to start pointing and communicating. My (www.strangeson.com) will become a gathering own son Dov began to communicate for the first time place for people who have higher hopes for their when he was nine years old, after working with the nonverbal or ‘low-communicating’ children and that very talented Soma Mukhopadyay and it was then the content of the site will evolve over time to include that we learned he had normal intelligence. I spent many kinds of approaches and methods that have the next three years observing Soma and studying been successful in increasing communication. In this her as she worked with hundreds of children, all the way I hope that the intelligence of nonverbal and while struggling myself to learn how to communicate low-communicating people with autism will become with Dov the way she did. -

Autism Books & Website Resources

Autism Books & Website Resources A Parent’s Guide to Asperger Syndrome & High Functioning Autism –Sally Ozonof Asperger Syndrome Employment Workbook –Roger N. Meyer and Tony Attwood The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime (Novel) – Mark Haddon Asperger’s Huh? A child’s perspective - Rosing G. Schnurr and John Strachan Embarrassed Often, Ashamed Never – Lisa B. Elliott Emily Post Book of Etiquette Freaks, Geeks & Asperger Syndrome: A User Guide to Adolescence - Luke Jackson Is it “Just a Phase”? – Susan Anderson Swedo and Henrietta L. Leonard Look Me in the Eye: My Life with Asperger’s – John Elder Robison Room 14:A Social Language Program Activity Book – Carolyn C Wilson The Tough Kids : Social Skills Book – Susan M. Sheridan and Tom Oling Coping: A Survival Guide for People with Asperger Syndrome - Marc Segar The New Social Story Book - Carol Gray Rules – Cynthia Lord Aspertools – Harold Reitman A Practical Guide to Day-to-Day Life Social Skills for Teenagers and Adults with Asperger Syndrome - Nancy J. Patrick Asperger Syndrome And Difficult Moments: Practical Solutions For Tantrums, Rage And Meltdowns - Brenda Smith Myles and Jack Southwick Asperger Syndrome and Employment: What People With Asperger Syndrome Really Really Want - Sarah Hendrickx The Autism Sourcebook: Everything You Need to Know About Diagnosis, Treatment, Coping, and Healing - Karen Siff Exkorn Girls Under the Umbrella of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Practical Solutions for Addressing Everyday Challenges - Lori, Ph.D. Ernsperger and Danielle Wendel Aspergirls: Empowering Females With Asperger Syndrome - Rudy Simone Navigating the Social World: A Curriculum for Individuals with Asperger's Syndrome, High Functioning Autism and Related Disorders - McAfee, J.; 2002). -

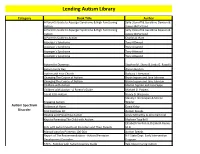

Lending Library

Lending Autism Library Category Book Title Author A Parent's Guide to Asperger Syndrome & High Functioning Sally Ozonoff & Geraldine Dawson & Autism James McPartland A Parent's Guide to Asperger Syndrome & High Functioning Sally Ozonoff & Geraldine Dawson & Autism James McPartland A Parent's Guide to Autism Charles A. Hart Asperger's Syndrome Tony Attwood Asperger's Syndrome Tony Attwood Asperger's Syndrome Tony Attwood Asperger's Syndrome Tony Attwood Autism for Dummies Stephen M. Shore & Linda G. Rastelli Autism Every Day Alyson Beytien Autism and Your Church Barbara J. Newman Changing The Course of Autism Bryan Jepson and Jane Johnson Changing The Course of Autism Bryan Jepson and Jane Johnson Children with Autism Marian Sigman and Lisa Capps Children with Autism - A Parent's Guide Michael D. Powers Could It Be Autism Nancy D. Wiseman Stanley I. Greenspan & Serena Engaging Autism Wieder Autism Spectrum Evidence of Harm David Kirby Disorder First 100 Days Kit Autism Speaks Healing and Preventing Autism Jenny McCarthy & Jerry Kartzinel Keys to Parenting The Child with Autism Marlene Targ Brill Elizabeth Verdick & Elizabeth Reeve, Kids with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Their Parents M.D Manual para los Primeros 100 Días Autism Speaks Report of The Recommendations - Autism/Pervasive N.Y State Dept. Early Intervention Development Disorders Program TACA - Families with Autism Journey Guide Talk About Curing Autism Autism Spectrum Disorder Lending Autism Library Category Book Title Author TACA - Families with Autism Journey Guide -Early -

Students with Autism: a Light/Sound Technology Intervention

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1996 Students with autism: A light/sound technology intervention Patricia Powell Woodbury College of William & Mary - School of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Educational Psychology Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, and the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Woodbury, Patricia Powell, "Students with autism: A light/sound technology intervention" (1996). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539618724. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25774/w4-84wg-4h14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Use of Clinical Judgment in Differentiating Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder from Those of Other Childhood Conditions: a Delphi Study

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2019 The Use of Clinical Judgment in Differentiating Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder from Those of Other Childhood Conditions: A Delphi Study Staci Jordan University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the School Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Jordan, Staci, "The Use of Clinical Judgment in Differentiating Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder from Those of Other Childhood Conditions: A Delphi Study" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1587. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1587 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. The Use of Clinical Judgment in Differentiating Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder From Those of Other Childhood Conditions: A Delphi Study A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Morgridge College of Education University of Denver ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ____________ by Staci Jordan June 2019 Advisor: Dr. Devadrita Talapatra ©Copyright by Staci Jordan 2019 All Rights Reserved Abstract Author: Staci Jordan Title: The Use of Clinical Judgment in Differentiating Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder From Those of Other Childhood Conditions: A Delphi Study Advisor: Dr. Devadrita Talapatra Degree Date: June 2019 Abstract More and more, due to long waiting lists at diagnostic clinics and access barriers for certain segments of the population, schools are often the first environment in which children are evaluated for ASD (Sullivan, 2013).