IFE and Wlldll ITAT of AMERICAN SA VIRONMENT and ECOLO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thymelaeaceae)

Origin and diversification of the Australasian genera Pimelea and Thecanthes (Thymelaeaceae) by MOLEBOHENG CYNTHIA MOTS! Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR in BOTANY in the FACULTY OF SCIENCE at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Dr Michelle van der Bank Co-supervisors: Dr Barbara L. Rye Dr Vincent Savolainen JUNE 2009 AFFIDAVIT: MASTER'S AND DOCTORAL STUDENTS TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This serves to confirm that I Moleboheng_Cynthia Motsi Full Name(s) and Surname ID Number 7808020422084 Student number 920108362 enrolled for the Qualification PhD Faculty _Science Herewith declare that my academic work is in line with the Plagiarism Policy of the University of Johannesburg which I am familiar. I further declare that the work presented in the thesis (minor dissertation/dissertation/thesis) is authentic and original unless clearly indicated otherwise and in such instances full reference to the source is acknowledged and I do not pretend to receive any credit for such acknowledged quotations, and that there is no copyright infringement in my work. I declare that no unethical research practices were used or material gained through dishonesty. I understand that plagiarism is a serious offence and that should I contravene the Plagiarism Policy notwithstanding signing this affidavit, I may be found guilty of a serious criminal offence (perjury) that would amongst other consequences compel the UJ to inform all other tertiary institutions of the offence and to issue a corresponding certificate of reprehensible academic conduct to whomever request such a certificate from the institution. Signed at _Johannesburg on this 31 of _July 2009 Signature Print name Moleboheng_Cynthia Motsi STAMP COMMISSIONER OF OATHS Affidavit certified by a Commissioner of Oaths This affidavit cordons with the requirements of the JUSTICES OF THE PEACE AND COMMISSIONERS OF OATHS ACT 16 OF 1963 and the applicable Regulations published in the GG GNR 1258 of 21 July 1972; GN 903 of 10 July 1998; GN 109 of 2 February 2001 as amended. -

1 American Samoa Passive Acoustic Monitoring Site ROSE Rose Atoll

American Samoa Passive Acoustic Monitoring Site ROSE Rose Atoll, American Samoa Ecological Acoustic Recorder (EAR) 14-March-2008 to 16-July-2009 Level 1 Analysis of Passive Acoustic Observations1 Synopsis This document provides a level 1 analysis of the data obtained from ecological acoustic recorder (EAR) unit 9300638B041 deployed at Rose Atoll from March 12th 2008 to March 4th 2010. The EAR unit recorded acoustic data from March 14th 2008 to July 16th 2009. This initial report contains background information about the site, time-series of total acoustic energy, and analyses of event-triggered recordings. Background Monitoring the changing status of coral reef environments and associated biota is a critical management need and a considerable technological challenge, especially on reefs in remote locations. The Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center (PIFSC) Coral Reef Ecosystem Division (CRED), in partnership with the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB), is using natural ambient sounds as a way to characterize the activity of marine organisms on coral reefs and in surrounding waters. By deploying a device known as the Ecological Acoustic Recorder (EAR), a cost-effective tool for recording biological and anthropogenic sounds, CRED investigates and monitors the presence and activity of sound-producing marine life and human activity. The EAR can be left in place unattended for up to two years, depending on the instrument’s configuration. Passive acoustic observations are typically not compromised by bio-fouling. The EAR records the local ambient acoustic environment on a programmed schedule and is also triggered to record by high amplitude transient events, such as engine noise from passing vessels. -

American Samoa

Coral Reef Habitat Assessment for U.S. Marine Protected Areas: U.S. Territory of American Samoa National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NOAA’s National Ocean Service Management & Budget Office Special Projects February 2009 Project Overview About this Effort NCCOS Benthic Habitat Mapping Effort The United States Coral Reef Task Force (USCRTF), in both its National The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Action Plan to Conserve Coral Reefs (2000) and its National Coral Reef Ocean Service (NOS) initiated a coral reef research program in 1999 to Action Strategy (2002), established a key conservation objective of pro- map, assess, inventory, and monitor U.S. coral reef ecosystems (Monaco tecting at least 20% of U.S. coral reefs and associated habitat types in et al. 2001). These activities were implemented in response to require- no-take marine reserves. NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program has ments outlined in the Mapping Implementation Plan developed by the Map- been supporting efforts to assess current protection levels of coral reefs ping and Information Synthesis Working Group (MISWG) of the Coral Reef within Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and quantify the area of U.S. coral Task Force (CRTF) (MISWG 1999). NOS’s National Centers for Coastal reef ecosystems protected in no-take reserves. The official federal defini- Ocean Science (NCCOS) Biogeography Team was charged with the de- tion of an MPA, signed into law by Executive Order 13158, is “any area of velopment and implementation of a plan to produce comprehensive digital the marine environment that has been reserved by federal, state, tribal, coral-reef ecosystem maps for all U.S. -

Take Another Look

Take Contact Details Another SUNSHINE COAST REGIONAL COUNCIL Caloundra Customer Service Look..... 1 Omrah Avenue, Caloundra FRONT p: 07 5420 8200 e: [email protected] Maroochydore Customer Service 11-13 Ocean Street, Maroochydore p: 07 5475 8501 e: [email protected] Nambour Customer Service Cnr Currie & Bury Street, Nambour p: 07 5475 8501 e: [email protected] Tewantin Customer Service 9 Pelican Street, Tewantin p: 07 5449 5200 e: [email protected] YOUR LOCAL CONTACT Our Locals are Beauties HINTERLAND EDITION HINTERLAND EDITION 0 Local native plant guide 2 What you grow in your garden can have major impact, Introduction 3 for better or worse, on the biodiversity of the Sunshine Native plants 4 - 41 Coast. Growing a variety of native plants on your property can help to attract a wide range of beautiful Wildlife Gardening 20 - 21 native birds and animals. Native plants provide food and Introduction Conservation Partnerships 31 shelter for wildlife, help to conserve local species and Table of Contents Table Environmental weeds 42 - 73 enable birds and animals to move through the landscape. Method of removal 43 Choosing species which flower and fruit in different Succulent plants and cacti 62 seasons, produce different types of fruit and provide Water weeds 70 - 71 roost or shelter sites for birds, frogs and lizards can greatly increase your garden’s real estate value for native References and further reading 74 fauna. You and your family will benefit from the natural pest control, life and colour that these residents and PLANT TYPE ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFITS visitors provide – free of charge! Habitat for native frogs Tall Palm/Treefern Local native plants also improve our quality of life in Attracts native insects other ways. -

Marine Conservation Science & Monitoring

Sanctuary Advisory Council UPDATE: January - August 2015 CULTURAL HERITAGE & COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT In February 2015, the National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa (sanctuary) launched American Samoa "Get into Your Sanctuary (GIYS)" cam- paign that will run through October 2015. The campaign highlights communities, partnerships and the special places of the sanctuary. Additionally, the campaign includes community and outreach events as well as eco-tours led by sanctuary community members. GIYS LAUNCH: Over 200 government leaders, community UPCOMING EVENTS members, local residents, and students filled the Ocean Center for the February launch of the "Get into Your Sanc- September 3rd @ 9am tuary" Campaign where 200 students from 13 different schools pledged “Ta’iala mo le Sami" (Ocean Action Initia- Ocean Center - Google Street and Catlin Seaview Survey Launch tives) to further efforts to conserve natural and cultural re- sources for a better tomorrow for American Samoa. Richard September 4th @ 9am Vevers, Executive Director of Catlin Seaview Survey, pre- sented on the recent global coral bleaching event that im- Ocean Center - Sanctuary Advisory Council Meeting pacted the Territory’s reefs. He also compared bleaching September 19th @ 9am - 12pm imagery from February with pre-bleaching 360 degree im- agery captured during a visit in December 2014. Malaloa Dock – SSV Robert C. Seamans Open House GIYS SITE EVENTS: In March the Fagatele Bay event drew more than 200 visitors that explored the wonders of this ocean treasure and its unique surroundings. Tours included information on sanctuary programs, birds, veg- etation, an umu/weaving/traditional food tasting and hike down to the bay. 200 people participated in the Aunu’u “GIYS” event in April. -

Phylogeny of the Tropical Tree Family Dipterocarpaceae Based on Nucleotide Sequences of the Chloroplast Rbcl Gene1

American Journal of Botany 86(8): 1182±1190. 1999. PHYLOGENY OF THE TROPICAL TREE FAMILY DIPTEROCARPACEAE BASED ON NUCLEOTIDE SEQUENCES OF THE CHLOROPLAST RBCL GENE1 S. DAYANANDAN,2,6 PETER S. ASHTON,3 SCOTT M. WILLIAMS,4 AND RICHARD B. PRIMACK2 2Biology Department, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215; 3Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138; and 4Division of Biomedical Sciences, Meharry Medical College, 1005 D. B. Todd, Jr. Boulevard, Nashville, Tennessee 37208 The Dipterocarpaceae, well-known trees of the Asian rain forests, have been variously assigned to Malvales and Theales. The family, if the Monotoideae of Africa (30 species) and South America and the Pakaraimoideae of South America (one species) are included, comprises over 500 species. Despite the high diversity and ecological dominance of the Dipterocar- paceae, phylogenetic relationships within the family as well as between dipterocarps and other angiosperm families remain poorly de®ned. We conducted parsimony analyses on rbcL sequences from 35 species to reconstruct the phylogeny of the Dipterocarpaceae. The consensus tree resulting from these analyses shows that the members of Dipterocarpaceae, including Monotes and Pakaraimaea, form a monophyletic group closely related to the family Sarcolaenaceae and are allied to Malvales. The present generic and higher taxon circumscriptions of Dipterocarpaceae are mostly in agreement with this molecular phylogeny with the exception of the genus Hopea, which forms a clade with Shorea sections Anthoshorea and Doona. Phylogenetic placement of Dipterocarpus and Dryobalanops remains unresolved. Further studies involving repre- sentative taxa from Cistaceae, Elaeocarpaceae, Hopea, Shorea, Dipterocarpus, and Dryobalanops will be necessary for a comprehensive understanding of the phylogeny and generic limits of the Dipterocarpaceae. -

Program in American Samoa: 2015 Report

THE TROPICAL MONITORING AVIAN PRODUCTIVITY AND SURVIVORSHIP (TMAPS) PROGRAM IN AMERICAN SAMOA: 2015 REPORT Peter Pyle, Kim Kayano, Jessie Reese, Vicki Morgan, Robinson Seumanutafa Mulitalo, Joshua Tigilau, Salefu Tuvalu, Danielle Kaschube, Ron Taylor, and Lauren Helton 30 September 2015 PO Box 1346 PO Box 3730 Point Reyes Station, CA 94956 Pago Pago, American Samoa 96799 Robinson S. Mulitalo banding a Many-colored Fruit-Dove at the Mt. Alava TMAPS station Suggested citation: Pyle, P., K. Kayano, J. Reese, V. Morgan, R. S. Mulitalo, J. Tigilau, S. Tuvalu, D. Kaschube, R. Taylor, and L. Helton. 2015. The Tropical Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (TMAPS) Program in American Samoa: 2015 Report. The Institute for Bird Populations, Point Reyes Station, CA. Cover photograph by Kim Kayano. The Institute for Bird Populations American Samoa 2015 TMAPS Report 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Few data exist on the ecology, population status, and conservation needs of landbirds in American Samoa. In an effort to provide baseline population data for these species and to address potential conservation concerns, we initiated a Tropical Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (TMAPS) program on Tutuila Island in 2012, expanded it to Ta'u Island in 2013, and continued operation on both islands in 2014-2015. Long-term goals of this project are to: (1) provide annual indices of adult population size and post-fledging productivity; (2) provide annual estimates of adult population densities, adult survival rates, proportions of residents, and recruitment into the adult population (from capture-recapture data); (3) relate avian demographic data to weather and habitat; (4) identify proximate and ultimate causes of population change; (5) use monitoring data to inform management; and (6) assess the success of managements actions in an adaptive management framework. -

Endiandric Acid Derivatives and Other Constituents of Plants from the Genera Beilschmiedia and Endiandra (Lauraceae)

Biomolecules 2015, 5, 910-942; doi:10.3390/biom5020910 OPEN ACCESS biomolecules ISSN 2218-273X www.mdpi.com/journal/biomolecules/ Review Endiandric Acid Derivatives and Other Constituents of Plants from the Genera Beilschmiedia and Endiandra (Lauraceae) Bruno Ndjakou Lenta 1,2,*, Jean Rodolphe Chouna 3, Pepin Alango Nkeng-Efouet 3 and Norbert Sewald 2 1 Department of Chemistry, Higher Teacher Training College, University of Yaoundé 1, P.O. Box 47, Yaoundé, Cameroon 2 Organic and Bioorganic Chemistry, Chemistry Department, Bielefeld University, P.O. Box 100131, 33501 Bielefeld, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Chemistry, University of Dschang, P.O. Box 67, Dschang, Cameroon; E-Mails:[email protected] (J.R.C.); [email protected] (P.A.N.-E.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +2376-7509-7561. Academic Editor: Jürg Bähler Received: 3 March 2015 / Accepted: 6 May 2015 / Published: 14 May 2015 Abstract: Plants of the Lauraceae family are widely used in traditional medicine and are sources of various classes of secondary metabolites. Two genera of this family, Beilschmiedia and Endiandra, have been the subject of numerous investigations over the past decades because of their application in traditional medicine. They are the only source of bioactive endiandric acid derivatives. Noteworthy is that their biosynthesis contains two consecutive non-enzymatic electrocyclic reactions. Several interesting biological activities for this specific class of secondary metabolites and other constituents of the two genera have been reported, including antimicrobial, enzymes inhibitory and cytotoxic properties. This review compiles information on the structures of the compounds described between January 1960 and March 2015, their biological activities and information on endiandric acid biosynthesis, with 104 references being cited. -

CHAPTER II Planning Area Profile for Hazard Mitigation Analysis

CHAPTER II Planning Area Profile for Hazard Mitigation Analysis 24 Territory of American Samoa Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan A U.S. Territory since 1900, American Samoa is located in the central South Pacific Ocean, 2,300 miles south-southwest of Hawaii and 1,600 miles east-northeast of New Zealand. American Samoa has a total land area of approximately 76 square miles and consists of a group of five volcanic islands and two atolls (Rose Atoll and Swains Island). The five volcanic islands, Tutuila, Aunu’u, Ofu, Olosega, and Ta’u, are the major inhabited islands. Tutuila is the largest island and the center of government. Ofu, Olosega, and Ta’u, collectively are referred to as the Manu’a Islands. Figure 1 Base Map of American Samoa depicts all of the islands of American Samoa. Figure 1. Base Map of American Samoa. The five volcanic islands, Tutuila, Aunu’u, Ofu, Olosega, and Ta’u, are the inhabited islands. At 53 square miles, Tutuila is the largest and oldest of the islands, and is the center of government and business. It is a long, narrow island lying SW-NE, is just over 20 miles in length, and ranges from 1 to 2 miles wide in the eastern half, and from 2 to 5 miles wide in the western half. Home to 95 percent of the territory’s 55,000 residents, Tutuila is the historic capitol (Pago Pago), the seat of American Samoa’s legislature and judiciary (Fagatogo), as well as the office of the Governor. Tutuila is often divided into 3 regions: the eastern district, the western district and Manu’a district. -

American Samoa

Date visited: November 8, 2016 American Samoa Previous (American Revolutionary War) (/entry/American_Revolutionary_War) Next (American civil religion) (/entry/American_civil_religion) American Samoa Amerika Sāmoa / Sāmoa Amelika is an unorganized, American Samoa incorporated territory of the United States (/entry/File:American_samoa_coa.png) (/entry/File:Flag_of_American_Samoa.svg) Flag Coat of arms Motto: "Samoa, Muamua Le Atua" (Samoan) "Samoa, Let God Be First" Anthem: The StarSpangled Banner, Amerika Samoa (/entry/File:LocationAmericanSamoa.png) Capital Pago Pago1 (de facto (/entry/De_facto)), Fagatogo (seat of (/entry/List_of_national_capitals) government) Official languages English, Samoan Government President Barack Obama (/entry/Barack_Obama) (D) Governor Togiola Tulafono (D) Lieutenant Governor Ipulasi Aitofele Sunia (D) Unincorporated territory of the United States (/entry/United_States) Tripartite Convention 1899 Deed of Cession of Tutuila 1900 Deed of Cession of Manu'a 1904 Annexation of Swains Island 1925 Area (/entry/List_of_countries_and_outlying_territories_by_area) Date visited: November 8, 2016 199 km² (212th Total (/entry/List_of_countries_and_outlying_territories_by_area)) 76.83 sq mi Water (%) 0 Population 2009 estimate 66,432 2000 census 57,291 326/km² Density 914/sq mi GDP (/entry/Gross_domestic_product) 2007 estimate (PPP) Total $575.3 million Per capita (/entry/Per_capita) Currency (/entry/Currency) US dollar (USD) Internet TLD (/entry/List_of_Internet_top .as level_domains) Calling code ++1684 (/entry/List_of_country_calling_codes) (/entry/United_States), located in the South Pacific Ocean (/entry/Pacific_Ocean) southeast of the sovereign state of Samoa (/entry/Samoa). The native inhabitants of its 70,000 people are descended from seafaring Polynesians (/entry/Polynesia) who populated many islands in the South Pacific. It is a destination spot of many vacationers due to its seasonally sublime climate and miles of clear sandy beaches. -

Jungle Myna (Acridotheres Fuscus)

Invasive animal risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Jungle myna Acridotheres fuscus Steve Csurhes First published 2011 Updated 2016 © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Front cover: Jungle myna Photo: Used with permission, Wikimedia Commons. Invasive animal risk assessment: Jungle myna Acridotheres fuscus 2 Contents Summary 4 Introduction 5 Identity and taxonomy 5 Description and biology 5 Diet 5 Reproduction 5 Preferred habitat and climate 6 Native range and global distribution 6 Current distribution and impact in Queensland 6 History as a pest overseas 7 Use 7 Potential distribution and impact in Queensland 7 References 8 Invasive animal risk assessment: Jungle myna Acridotheres fuscus 3 Summary Acridotheres fuscus (jungle myna) is native to an extensive area of India and parts of southeast Asia. Naturalised populations exist in Singapore, Taiwan, Fiji, Western Samoa and elsewhere. In Fiji, the species occasionally causes significant damage to crops of ground nuts, with crop losses of up to 40% recorded. Within its native range (South India), it is not a well documented pest, but occasionally causes considerable (localised) damage to fruit orchards. -

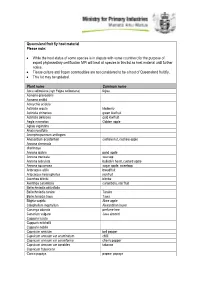

MPI Queensland Fruit Fly Host Material List

Queensland fruit fly host material Please note: While the host status of some species is in dispute with some countries; for the purpose of export phytosanitary certification MPI will treat all species in this list as host material until further notice. Tissue culture and frozen commodities are not considered to be a host of Queensland fruit fly. This list may be updated. Plant name Common name Acca sellowiana (syn Feijoa sellowiana) feijoa Acmena graveolens Acmena smithii Acroychia acidula Actinidia arguta kiwiberry Actinidia chinensis green kiwifruit Actinidia deliciosa gold kiwifruit Aegle marmelos Golden apple Aglaia sapindina Alyxia ruscifolia Amorphospermum antilogum Anacardium occidentale cashew nut, cashew apple Annona cherimola cherimoya Annona glabra pond apple Annona muricata soursop Annona reticulata bullock's heart, custard apple Annona squamosa sugar apple, sweetsop Artocarpus altilis breadfruit Artocarpus heterophyllus jackfruit Averrhoa bilimbi blimbe Averrhoa carambola carambola, star fruit Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Beilschmiedia taraire Taraire Beilschmiedia tawa Tawa Blighia sapida Akee apple Calophyllum inophyllum Alexandrian laurel Cananga odorata perfume tree Canarium vulgare Java almond Capparis lucida Capparis mitchellii Capparis nobilis Capsicum annuum bell pepper Capsicum annuum var acuminatum chilli Capsicum annuum var cerasiforme cherry pepper Capsicum annuum var conoides tabasco Capsicum frutescens Carica papaya papaw, papaya Carica pentagona babaco Carissa ovata Casimiroa edulis white sapote Cassine australia Castanospora alphandii Chrysophyllum cainito caimito, star apple Cissus sp Citrullus lanatus Watermelon Citrus spp. Citrus aurantiifolia West indian lime Citrus aurantium Seville orange Citrus grandis (syn maxima) pummelo Citrus hystrix kaffir lime Citrus jambhiri rough lemon Citrus latifolia Tahatian lime Citrus limetta sweet lemon tree Citrus limon lemon Citrus maxima (syn grandis) pomelo, shaddock Citrus medica citron Citrus meyeri Meyer lemon Citrus reticulata mandarin Citrus reticulata var.