A Genetic Variant in Proximity to the Gene LYPLAL1 Is Associated with Lower Hunger Feelings and Increased Weight Loss Following Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cell, Volume 139 Supplemental Data Profiling the Human Protein-DNA

Cell, Volume 139 Supplemental Data Profiling the Human Protein-DNA Interactome Reveals ERK2 as a Transcriptional Repressor of Interferon Signaling Shaohui Hu, Zhi Xie, Akishi Onishi, Xueping Yu, Lizhi Jiang, Jimmy Lin, Hee-sool Rho, Crystal Woodard, Hong Wang, Jun-Seop Jeong, Shunyou Long, Xiaofei He, Herschel Wade, Seth Blackshaw, Jiang Qian, and Heng Zhu Supplemental Experimental Procedures Identifying Tissue-specific Motifs We developed a program to identify tissue-specific motifs. We first defined sets of tissue-specific or tissue-enriched genes by examining their gene expression profiles across multiple tissues (Yu et al., 2006). We then calculated the most over-represented single motifs (8-mers, including a wide character) in the promoters of each set of tissue-specific genes. The program then enumerated all possible combinations of the top n motifs (e.g. n = 100). For each motif pair, the program recorded the occurrence of the motif pair in the promoter sequences. We then calculated the significance score for each motif pair, which was defined as the negative logarithm of the p value, -log(p). The motif pairs with scores above a specified threshold were considered putative TF binding motif pairs in the promoter sequences. With these predicted motif pairs, we could calculate a number of partners for each motif and select a certain number of top non-redundant motifs to be tested in the protein chip experiments. Both the p values for a single motif and those for a motif pair were calculated using hypergeometric distribution. Here, we use a motif pair as an example to show the ij, procedure. -

Investigation of Candidate Genes and Mechanisms Underlying Obesity

Prashanth et al. BMC Endocrine Disorders (2021) 21:80 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-021-00718-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Investigation of candidate genes and mechanisms underlying obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus using bioinformatics analysis and screening of small drug molecules G. Prashanth1 , Basavaraj Vastrad2 , Anandkumar Tengli3 , Chanabasayya Vastrad4* and Iranna Kotturshetti5 Abstract Background: Obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder ; however, the etiology of obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus remains largely unknown. There is an urgent need to further broaden the understanding of the molecular mechanism associated in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Methods: To screen the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that might play essential roles in obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus, the publicly available expression profiling by high throughput sequencing data (GSE143319) was downloaded and screened for DEGs. Then, Gene Ontology (GO) and REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis were performed. The protein - protein interaction network, miRNA - target genes regulatory network and TF-target gene regulatory network were constructed and analyzed for identification of hub and target genes. The hub genes were validated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and RT- PCR analysis. Finally, a molecular docking study was performed on over expressed proteins to predict the target small drug molecules. Results: A total of 820 DEGs were identified between -

The Metabolic Serine Hydrolases and Their Functions in Mammalian Physiology and Disease Jonathan Z

REVIEW pubs.acs.org/CR The Metabolic Serine Hydrolases and Their Functions in Mammalian Physiology and Disease Jonathan Z. Long* and Benjamin F. Cravatt* The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and Department of Chemical Physiology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States CONTENTS 2.4. Other Phospholipases 6034 1. Introduction 6023 2.4.1. LIPG (Endothelial Lipase) 6034 2. Small-Molecule Hydrolases 6023 2.4.2. PLA1A (Phosphatidylserine-Specific 2.1. Intracellular Neutral Lipases 6023 PLA1) 6035 2.1.1. LIPE (Hormone-Sensitive Lipase) 6024 2.4.3. LIPH and LIPI (Phosphatidic Acid-Specific 2.1.2. PNPLA2 (Adipose Triglyceride Lipase) 6024 PLA1R and β) 6035 2.1.3. MGLL (Monoacylglycerol Lipase) 6025 2.4.4. PLB1 (Phospholipase B) 6035 2.1.4. DAGLA and DAGLB (Diacylglycerol Lipase 2.4.5. DDHD1 and DDHD2 (DDHD Domain R and β) 6026 Containing 1 and 2) 6035 2.1.5. CES3 (Carboxylesterase 3) 6026 2.4.6. ABHD4 (Alpha/Beta Hydrolase Domain 2.1.6. AADACL1 (Arylacetamide Deacetylase-like 1) 6026 Containing 4) 6036 2.1.7. ABHD6 (Alpha/Beta Hydrolase Domain 2.5. Small-Molecule Amidases 6036 Containing 6) 6027 2.5.1. FAAH and FAAH2 (Fatty Acid Amide 2.1.8. ABHD12 (Alpha/Beta Hydrolase Domain Hydrolase and FAAH2) 6036 Containing 12) 6027 2.5.2. AFMID (Arylformamidase) 6037 2.2. Extracellular Neutral Lipases 6027 2.6. Acyl-CoA Hydrolases 6037 2.2.1. PNLIP (Pancreatic Lipase) 6028 2.6.1. FASN (Fatty Acid Synthase) 6037 2.2.2. PNLIPRP1 and PNLIPR2 (Pancreatic 2.6.2. -

Application to Neuroimaging Biomarkers in Alzheimer's

The Author(s) BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2017, 17(Suppl 1):61 DOI 10.1186/s12911-017-0454-0 RESEARCH Open Access Knowledge-driven binning approach for rare variant association analysis: application to neuroimaging biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease Dokyoon Kim1,2, Anna O. Basile2, Lisa Bang1, Emrin Horgusluoglu4, Seunggeun Lee3, Marylyn D. Ritchie1,2, Andrew J. Saykin4 and Kwangsik Nho4* From The 6th Translational Bioinformatics Conference Je Ju Island, Korea. 15-17 October 2016 Abstract Background: Rapid advancement of next generation sequencing technologies such as whole genome sequencing (WGS) has facilitated the search for genetic factors that influence disease risk in the field of human genetics. To identify rare variants associated with human diseases or traits, an efficient genome-wide binning approach is needed. In this study we developed a novel biological knowledge-based binning approach for rare-variant association analysis and then applied the approach to structural neuroimaging endophenotypes related to late-onset Alzheimer’sdisease(LOAD). Methods: For rare-variant analysis, we used the knowledge-driven binning approach implemented in Bin-KAT, an automated tool, that provides 1) binning/collapsing methods for multi-level variant aggregation with a flexible, biologically informed binning strategy and 2) an option of performing unified collapsing and statistical rare variant analyses in one tool. A total of 750 non-Hispanic Caucasian participants from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort who had both WGS data and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were used in this study. Mean bilateral cortical thickness of the entorhinal cortex extracted from MRI scans was used as an AD-related neuroimaging endophenotype. -

Long Noncoding RNA LYPLAL1-AS1 Regulates Adipogenic Differentiation

Yang et al. Cell Death Discovery (2021) 7:105 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-021-00500-5 Cell Death Discovery ARTICLE Open Access Long noncoding RNA LYPLAL1-AS1 regulates adipogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by targeting desmoplakin and inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway Yanlei Yang1,2,JunfenFan1,HaoyingXu1,LinyuanFan1,LuchanDeng1,JingLi 1,DiLi1, Hongling Li1, Fengchun Zhang2 and Robert Chunhua Zhao1 Abstract Long noncoding RNAs are crucial factors for modulating adipogenic differentiation, but only a few have been identified in humans. In the current study, we identified a previously unknown human long noncoding RNA, LYPLAL1- antisense RNA1 (LYPLAL1-AS1), which was dramatically upregulated during the adipogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hAMSCs). Based on 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends assays, full- length LYPLAL1-AS1 was 523 nt. Knockdown of LYPLAL1-AS1 decreased the adipogenic differentiation of hAMSCs, whereas overexpression of LYPLAL1-AS1 enhanced this process. Desmoplakin (DSP) was identified as a direct target of LYPLAL1-AS1. Knockdown of DSP enhanced adipogenic differentiation and rescued the LYPLAL1-AS1 depletion- induced defect in adipogenic differentiation of hAMSCs. Further experiments showed that LYPLAL1-AS1 modulated DSP protein stability possibly via proteasome degradation, and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway was inhibited during 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; adipogenic differentiation regulated by the LYPLAL1-AS1/DSP complex. Together, our work provides a new mechanism by which long noncoding RNA regulates adipogenic differentiation of human MSCs and suggests that LYPLAL1-AS1 may serve as a novel therapeutic target for preventing and combating diseases related to abnormal adipogenesis, such as obesity. -

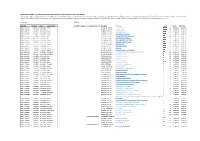

Supp Table 2

Supplementary Table 2 : Transcripts and pathways down-regulated in SLE compared to control renal biopsies Differences in (Log2-transformed, mean-centered) gene expression between lupus and control biopsies were analyzed using a moderated t test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons (p value threshold set to 0.05). Pathway analyses were performed using DAVID software. Enrichment scores are –log10 p values, calculated by modified Fisher Exact test by comparing proportions of transcripts belonging to a given pathway in the tested gene list compared to the whole transcriptome.[14, 15] Transcripts Pathways Identifier [Control] [SLE] Gene Symbol Annotation Cluster 1 Enrichment Score: 7.43 Database Pathway Count P_Value Benjamini ILMN_1751607 2.8195102 0.25910223 FOSB SP_PIR_KEYWORDS mitochondrion 52 6.80E-20 2.30E-17 ILMN_1682763 2.1716797 -0.4070203 ALB GOTERM_CC_FAT mitochondrion 60 2.70E-19 7.50E-17 ILMN_1781285 1.7535293 -0.0462692 DUSP1 GOTERM_CC_FAT mitochondrial part 42 7.40E-17 1.50E-14 ILMN_1723522 1.718832 -0.2997489 APOLD1 GOTERM_CC_FAT mitochondrial enveLope 34 3.00E-15 2.80E-13 ILMN_1765232 1.632873 0.14076953 RNLS GOTERM_CC_FAT mitochondrial inner membrane 28 8.40E-14 5.80E-12 ILMN_1662880 1.6177534 -0.1763568 FIS GOTERM_CC_FAT mitochondrial membrane 31 1.50E-13 8.60E-12 ILMN_1813361 1.6158535 0.08449265 ANGPTL7 UP_SEQ_FEATURE tranSit peptide:Mitochondrion 32 3.90E-13 2.80E-10 ILMN_2047618 1.6081884 -0.0522185 KCNE1 GOTERM_CC_FAT organeLLe inner membrane 28 4.80E-13 2.20E-11 ILMN_1711015 1.577714 -0.2619377 -

Genomic and Transcriptome Analysis Revealing an Oncogenic Functional Module in Meningiomas

Neurosurg Focus 35 (6):E3, 2013 ©AANS, 2013 Genomic and transcriptome analysis revealing an oncogenic functional module in meningiomas XIAO CHANG, PH.D.,1 LINGLING SHI, PH.D.,2 FAN GAO, PH.D.,1 JONATHAN RUssIN, M.D.,3 LIYUN ZENG, PH.D.,1 SHUHAN HE, B.S.,3 THOMAS C. CHEN, M.D.,3 STEVEN L. GIANNOTTA, M.D.,3 DANIEL J. WEISENBERGER, PH.D.,4 GAbrIEL ZADA, M.D.,3 KAI WANG, PH.D.,1,5,6 AND WIllIAM J. MAck, M.D.1,3 1Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California; 2GHM Institute of CNS Regeneration, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China; 3Department of Neurosurgery, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California; 4USC Epigenome Center, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California; 5Department of Psychiatry, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California; and 6Division of Bioinformatics, Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California Object. Meningiomas are among the most common primary adult brain tumors. Although typically benign, roughly 2%–5% display malignant pathological features. The key molecular pathways involved in malignant trans- formation remain to be determined. Methods. Illumina expression microarrays were used to assess gene expression levels, and Illumina single- nucleotide polymorphism arrays were used to identify copy number variants in benign, atypical, and malignant me- ningiomas (19 tumors, including 4 malignant ones). The authors also reanalyzed 2 expression data sets generated on Affymetrix microarrays (n = 68, including 6 malignant ones; n = 56, including 3 malignant ones). -

I STRUCTURE and FUNCTION of the PALMITOYLTRANSFERASE

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE PALMITOYLTRANSFERASE DHHC20 AND THE ACYL COA HYDROLASE MBLAC2 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Martin Ian Paguio Malgapo December 2019 i © 2019 Martin Ian Paguio Malgapo ii STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE PALMITOYLTRANSFERASE DHHC20 AND THE ACYL COA HYDROLASE MBLAC2 Martin Ian Paguio Malgapo, Ph.D. Cornell University 2019 My graduate research has focused on the enzymology of protein S-palmitoylation, a reversible posttranslational modification catalyzed by DHHC palmitoyltransferases. When I started my thesis work, the structure of DHHC proteins was not known. I sought to purify and crystallize a DHHC protein, identifying DHHC20 as the best target. While working on this project, I came across a protein of unknown function called metallo-β-lactamase domain-containing protein 2 (MBLAC2). A proteomic screen utilizing affinity capture mass spectrometry suggested an interaction between MBLAC2 (bait) and DHHC20 (hit) in HEK-293 cells. This finding interested me initially from the perspective of finding an interactor that could help stabilize DHHC20 into forming better quality crystals as well as discovering a novel protein substrate for DHHC20. I was intrigued by MBLAC2 upon learning that this protein is predicted to be palmitoylated by multiple proteomic screens. Additionally, sequence analysis predicts MBLAC2 to have thioesterase activity. Taken together, studying a potential new thioesterase that is itself palmitoylated was deemed to be a worthwhile project. When the structure of DHHC20 was published in 2017, I decided to switch my efforts to characterizing MBLAC2. -

View Full Page

The Journal of Neuroscience, June 15, 2016 • 36(24):6431–6444 • 6431 Cellular/Molecular Identification of PSD-95 Depalmitoylating Enzymes Norihiko Yokoi,1,3* Yuko Fukata,1,3*,‡ Atsushi Sekiya,1,3 Tatsuro Murakami,1,3 Kenta Kobayashi,2,3 and Masaki Fukata1,3‡ 1Division of Membrane Physiology, Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology and 2Section of Viral Vector Development, Center for Genetic Analysis of Behavior, National Institute for Physiological Sciences (NIPS), National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS), and 3Department of Physiological Sciences, School of Life Science, SOKENDAI (The Graduate University for Advanced Studies), Okazaki, Aichi 444-8787, Japan Postsynaptic density (PSD)-95, the most abundant postsynaptic scaffolding protein, plays a pivotal role in synapse development and function. Continuous palmitoylation cycles on PSD-95 are essential for its synaptic clustering and regulation of AMPA receptor function. However,molecularmechanismsforpalmitatecyclingonPSD-95remainincompletelyunderstood,asPSD-95depalmitoylatingenzymes remain unknown. Here, we isolated 38 mouse or rat serine hydrolases and found that a subset specifically depalmitoylated PSD-95 in heterologous cells. These enzymes showed distinct substrate specificity. ␣/-Hydrolase domain-containing protein 17 members (ABHD17A, 17B, and 17C), showing the strongest depalmitoylating activity to PSD-95, showed different localization from other candi- dates in rat hippocampal neurons, and were distributed to recycling endosomes, the dendritic plasma membrane, and the synaptic fraction. Expression of ABHD17 in neurons selectively reduced PSD-95 palmitoylation and synaptic clustering of PSD-95 and AMPA receptors. Furthermore, taking advantage of the acyl-PEGyl exchange gel shift (APEGS) method, we quantitatively monitored the palmi- ␣ toylation stoichiometry and the depalmitoylation kinetics of representative synaptic proteins, PSD-95, GluA1, GluN2A, mGluR5, G q , and HRas. -

Genetics of Body Fat Distribution: Comparative Analyses in Populations with European, Asian and African Ancestries

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Genetics of Body Fat Distribution: Comparative Analyses in Populations with European, Asian and African Ancestries Chang Sun 1 , Peter Kovacs 1 and Esther Guiu-Jurado 1,2,* 1 Medical Department III–Endocrinology, Nephrology, Rheumatology, University of Leipzig Medical Center, 04103 Leipzig, Germany; [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (P.K.) 2 Deutsches Zentrum für Diabetesforschung, 85764 Neuherberg, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-341-9715895 Abstract: Preferential fat accumulation in visceral vs. subcutaneous depots makes obese individuals more prone to metabolic complications. Body fat distribution (FD) is regulated by genetics. FD patterns vary across ethnic groups independent of obesity. Asians have more and Africans have less visceral fat compared with Europeans. Consequently, Asians tend to be more susceptible to type 2 diabetes even with lower BMIs when compared with Europeans. To date, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified more than 460 loci related to FD traits. However, the majority of these data were generated in European populations. In this review, we aimed to summarize recent advances in FD genetics with a focus on comparisons between European and non-European populations (Asians and Africans). We therefore not only compared FD-related susceptibility loci identified in three ethnicities but also discussed whether known genetic variants might explain the FD pattern heterogeneity across different ancestries. Moreover, we describe several novel candidate genes potentially regulating FD, including NID2, HECTD4 and GNAS, identified in studies with Citation: Sun, C.; Kovacs, P.; Asian populations. -

Genome-Wide Association Study of Body Fat Distribution Identifies

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08000-4 OPEN Genome-wide association study of body fat distribution identifies adiposity loci and sex-specific genetic effects Mathias Rask-Andersen 1, Torgny Karlsson1, Weronica E. Ek1 & Åsa Johansson1 Body mass and body fat composition are of clinical interest due to their links to cardiovascular- and metabolic diseases. Fat stored in the trunk has been suggested to be more pathogenic 1234567890():,; compared to fat stored in other compartments. In this study, we perform genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for the proportion of body fat distributed to the arms, legs and trunk estimated from segmental bio-electrical impedance analysis (sBIA) for 362,499 indi- viduals from the UK Biobank. 98 independent associations with body fat distribution are identified, 29 that have not previously been associated with anthropometric traits. A high degree of sex-heterogeneity is observed and the effects of 37 associated variants are stronger in females compared to males. Our findings also implicate that body fat distribution in females involves mesenchyme derived tissues and cell types, female endocrine tissues as well as extracellular matrix maintenance and remodeling. 1 Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala University, Box 256, 751 05 Uppsala, Sweden. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.R.-A. (email: [email protected]) or to Å.J. (email: [email protected]) NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2019) 10:339 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08000-4 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08000-4 verweight (body mass index [BMI] > 25) and obesity mass, and between fat stored in different compartments of the O(BMI > 30) have reached epidemic proportions globally1. -

Lupus Nephritis Supp Table 5

Supplementary Table 5 : Transcripts and DAVID pathways correlating with the expression of CD4 in lupus kidney biopsies Positive correlation Negative correlation Transcripts Pathways Transcripts Pathways Identifier Gene Symbol Correlation coefficient with CD4 Annotation Cluster 1 Enrichment Score: 26.47 Count P_Value Benjamini Identifier Gene Symbol Correlation coefficient with CD4 Annotation Cluster 1 Enrichment Score: 3.16 Count P_Value Benjamini ILMN_1727284 CD4 1 GOTERM_BP_FAT translational elongation 74 2.50E-42 1.00E-38 ILMN_1681389 C2H2 zinc finger protein-0.40001984 INTERPRO Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme/RWD-like 17 2.00E-05 4.20E-02 ILMN_1772218 HLA-DPA1 0.934229063 SP_PIR_KEYWORDS ribosome 60 2.00E-41 4.60E-39 ILMN_1768954 RIBC1 -0.400186083 SMART UBCc 14 1.00E-04 3.50E-02 ILMN_1778977 TYROBP 0.933302249 KEGG_PATHWAY Ribosome 65 3.80E-35 6.60E-33 ILMN_1699190 SORCS1 -0.400223681 SP_PIR_KEYWORDS ubl conjugation pathway 81 1.30E-04 2.30E-02 ILMN_1689655 HLA-DRA 0.915891173 SP_PIR_KEYWORDS protein biosynthesis 91 4.10E-34 7.20E-32 ILMN_3249088 LOC93432 -0.400285215 GOTERM_MF_FAT small conjugating protein ligase activity 35 1.40E-04 4.40E-02 ILMN_3228688 HLA-DRB1 0.906190291 SP_PIR_KEYWORDS ribonucleoprotein 114 4.80E-34 6.70E-32 ILMN_1680436 CSH2 -0.400299744 SP_PIR_KEYWORDS ligase 54 1.50E-04 2.00E-02 ILMN_2157441 HLA-DRA 0.902996561 GOTERM_CC_FAT cytosolic ribosome 59 3.20E-33 2.30E-30 ILMN_1722755 KRTAP6-2 -0.400334007 GOTERM_MF_FAT acid-amino acid ligase activity 40 1.60E-04 4.00E-02 ILMN_2066066 HLA-DRB6 0.901531942 SP_PIR_KEYWORDS