(7,1-,„ • Ir STATE Government I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity Plan for the South East of South Australia 1999

SUMMARY Biodiversity Plan for the South East of South Australia 1999 rks & W Pa i Department for Environment ld l a l i f n e o i t Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs a N South Government of South Australia Australia AUTHORS Tim Croft (National Parks & Wildlife SA) Georgina House (QED) Alison Oppermann (National Parks & Wildlife SA) Ann Shaw Rungie (QED) Tatia Zubrinich (PPK Environment & Infrastructure Pty Ltd) CARTOGRAPHY AND DESIGN National Parks & Wildlife SA (Cover) Geographic Analysis and Research Unit, Planning SA Pierris Kahrimanis PPK Environment & Infrastructure Pty Ltd ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors are grateful to Professor Hugh Possingham, the Nature Conservation Society, and the South Australian Farmers Federation in providing the stimulus for the Biodiversity Planning Program and for their ongoing support and involvement Dr Bob Inns and Professor Possingham have also contributed significantly towards the information and design of the South East Biodiversity Plan. We also thank members of the South East community who have provided direction and input into the plan through consultation and participation in workshops © Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs, 1999 ISBN 0 7308 5863 4 Cover Photographs (top to bottom) Lowan phebalium (Phebalium lowanense) Photo: D.N. Kraehenbuehl Swamp Skink (Egernia coventryi) Photo: J. van Weenen Jaffray Swamp Photo: G. Carpenter Little Pygmy Possum (Cercartetus lepidus) Photo: P. Aitken Red-necked Wallaby (Macropus rufogriseus) Photo: P. Canty 2 diversity Plan for the South East of South Australia — Summary Foreword The conservation of our natural biodiversity is essential for the functioning of natural systems. Aside from the intrinsic importance of conserving the diversity of species many of South Australia's economic activities are based on the sustainable use, conservation and management of biodiversity. -

BLACKFORD RESERVE KIN S 06 Place Name and Address

BLACKFORD RESERVE KIN S 06 Place Name and Address: Blackford Reserve Rowney Road Blackford SA 5275 SUMMARY OF HERITAGE VALUE: Description: The Blackford Reserve consists of a large area of land bisected by Rowney Road. There are two stone cottages standing on the east side of the road, and one of stone and mixed materials on the west side. Most of the reserve is covered by native scrub, in a district where most land has been cleared for farming. Statement of Heritage Value: Commencing in about the 1880s, the Blackford Reserve was continuously occupied by an Indigenous community until the 1940s, and is still used today. It is the most substantial evidence of the historical and continuing relationship between European and Aboriginal people in the South-East. In addition, while there are a number of places entered in the SA Heritage Register because of their role in the interaction between European and Aboriginal South Australians, including all or part of the settlements at Poonindie, Moorundie, Point Pearce, Raukkan (Point McLeay) and Killalpaninna, all these settlements differ from Blackford Reserve in one fundamental respect. All were created, administered and supervised on a day-to-day basis by European staff. Most were run by church missionaries, Moorundie and Point Pearce by government officers, but all were European. Blackford is fundamentally different in being a settlement run entirely by and for its Aboriginal residents. Relevant Criteria (Under Section 16 of the Heritage Act 1993): (a) It demonstrates important aspects of the evolution or pattern of the State's history (d) It is an outstanding representative of a particular class of places of cultural significance RECOMMENDATION: It is recommended that the Blackford Reserve be provisionally entered in the South Australian Heritage Register, and that it be declared a place of archaeological significance. -

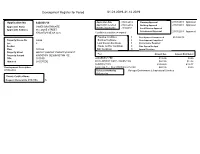

Development Register for Period 01.01.2019-31.12.2019

Development Register for Period 01.01.2019-31.12.2019 Application No 640/001/19 Application Date 07/01/2019 Planning Approval 21/01/2019 Approved Application received 07/01/2019 Building Approval 21/01/2019 Approved Applicants Name JAMES BRAITHWAITE Building Application 7/01/2019 Land Division Approval Applicants Address 66 COOKE STREET Development Approval 21/01/2019 Approved KINGSTON SE SA 5275 Conditions availabe on request Planning Conditions 3 Development Commenced 01/03/2019 Property House No 24ü24 Building Conditions 2 Development Completed Lot 2 Land Division Conditions 0 Concurrence Required Section Private Certifier Conditions 0 Date Appeal Lodged Plan D33844 DAC Conditions 0 Appeal Decision Property Street MARINEüMARINE PARADEüPARADE Fees Amount Due Amount Distributed Property Suburb KINGSTON SEüKINGSTON SE Title 5697/901 LODGEMENT FEE $136.00 $0.00 Hundred LACEPEDE DEVELOPMENT COST - COMPLYING $887.50 $44.38 BUILDING FEES $1,599.20 $101.77 Development Description Septic App. Fee -New CWMS/Onsite/Aerobic $457.00 $0.00 DWELLING Relevant Authority Manager Environment & Inspectorial Services Referred to Private Certifier Name Request Pursuant to R15 (7(b) N Development Register for Period 01.01.2019-31.12.2019 Application No 640/001/20 Application Date 07/01/2020 Planning Approval Application received 07/01/2020 Building Approval Applicants Name DW & SM SIEGERT Building Application 7/01/2020 Land Division Approval Applicants Address PO BOX 613 Development Approval NARACOORTE SA 5271 Conditions availabe on request Planning Conditions -

INVENTORY of ROCK TYPES, HABITATS, and BIODIVERSITY on ROCKY SEASHORES in SOUTH AUSTRALIA's TWO SOUTH-EAST MARINE PARKS: Pilot

INVENTORY OF ROCK TYPES, HABITATS, AND BIODIVERSITY ON ROCKY SEASHORES IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA’S TWO SOUTH-EAST MARINE PARKS: Pilot Study A report to the South Australian Department of Environment, Water, and Natural Resources Nathan Janetzki, Peter G. Fairweather & Kirsten Benkendorff June 2015 1 Table of contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Methods 5 Results 11 Discussion 32 References cited 42 Appendix 1: Photographic plates 45 Appendix 2: Graphical depiction of line-intercept transects 47 Appendix 3: Statistical outputs 53 2 Abstract Geological, habitat, and biodiversity inventories were conducted across six rocky seashores in South Australia’s (SA) two south-east marine parks during August 2014, prior to the final implementation of zoning and establishment of management plans for each marine park. These inventories revealed that the sampled rocky seashores in SA’s South East Region were comprised of several rock types: a soft calcarenite, Mount Gambier limestone, and/or a harder flint. Furthermore, these inventories identified five major types of habitat across the six sampled rocky seashores, which included: emersed substrate; submerged substrate; boulders; rock pools; and sand deposits. Overall, a total of 12 marine plant species and 46 megainvertebrate species were recorded across the six sampled seashores in the Lower South East and Upper South East Marine Parks. These species richness values are considerably lower than those recorded previously for rocky seashores in other parts of SA. Low species richness may result from the type of rock that constitutes south-east rocky seashores, the interaction between rock type and strong wave action and/or large swells, or may reflect the time of year (winter) during which these inventories were conducted. -

Camping in the District Council of Grant Council Is Working in the Best Interests of Its Community and Visitors to Ensure the Region Is a Great Place to Visit

Camping in the District Council of Grant Council is working in the best interests of its community and visitors to ensure the region is a great place to visit. Approved camping sites located in the District Council of Grant are listed below. Camping in public areas or sleeping in any type of vehicle in any residential or commercial area within the District Council of Grant is not permitted. For a complete list of available accommodation or further information please contact: Phone: 08 8738 3000 Port MacDonnell Community Complex & Visitor Information Outlet Email: [email protected] 5-7 Charles Street Web: portmacdonnell.sa.au OR dcgrant.sa.gov.au Port MacDonnell South Australia 5291 Location Closest Description Facilities Township Port MacDonnell Foreshore Port MacDonnell Powered & unpowered sites, on-site Tourist Park caravans, 20-bed lodge and cabins. Short Ph 08 8738 2095 walk to facilities and centre of town. www.woolwash.com.au 8 Mile Creek Road, Port MacDonnell Pine Country Caravan Park Mount Gambier Powered, unpowered, ensuite, drive thru Ph 8725 1899 sites and cabins. Short walking distance www.pinecountry.com.au from Blue Lake. Cnr Bay & Kilsby Roads, Mount Gambier. Canunda National Park Carpenter Rocks Campsites with varying degrees of access: Number Two Rocks Campground: www.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/Find_a_Park/ 7 unpowered campsites – book online Browse_by_region/Limestone_Coast/canunda- (4 wheel drive access only) national-park Cape Banks Campground: 6 unpowered campsites - book online Designated areas that offer *free camping for **self-contained vehicles only: Tarpeena Sports Ground Tarpeena Donation to Tarpeena Progress Association Edward Street appreciated. -

The Blue Lake - Frequently Asked Questions

The Blue Lake - Frequently Asked Questions FACT SHEET | JULY 2014 FAST FACTS Why does the Lake change Capacity: 30,000 megalitres on current levels. One colour? megalitre is 1000kL, one kilolitre is 1000 litres. The colour change happens over a few days in late November and early December and Depth: Maximum depth of 72m metres continues to deepen during summer. There are many theories about the famous colour Shoreline: Approximately 3.5km kilometres change of the lake, from grey in winter to vivid blue in summer – the following explanation Surface area: Approximately 70ha 59 hectares summarises the general understanding from recent research. Height above sea level: The crater rim is 100m 115 The clear water in the Blue Lake turns vibrant metres above sea level (at its highest point) and the blue in summer for two reasons. First, the Blue Lake water level 11.5m above sea level in 2007. The higher position of the sun in summer means lake level is approximately 28m below Commercial St more light hits the surface of the lake. This level increases the blue light that is scattered back out from the lake by small particles. Pure water Water supply: Currently SA Water pumps an average of tends to scatter light in the blue range, small 3500 megalitres per year particles (such as CaCO3 or calcium carbonate crystals) scatter light in the blue-green range Why is the Lake so blue? and dissolved organic matter (tannins) scatter in the yellow-brown range. The water in the Blue Lake is clear due to During spring the surface of the lake warms, several important natural cleaning processes. -

Mount Schank Mt Schank

South West Victoria & South East South Australia Craters and Limestone MT GAMBIER Precinct: Mount Schank Mt Schank PORT MacDONNELL How to get there? Mount Schank is 10 minutes south of Mount Gambier along the Riddoch Highway. Things to do: • Two steep walking trails offer a great geological experience. The Mount Schank is a highly prominent volcanic cone Viewing Platform Hike (900m return) begins at the car park located 10 minutes south of Mount Gambier, which and goes to the crater rim. From protrudes above the limestone plain, providing the top, overlooking the nearby panoramic views. quarry, evidence can be seen of the lava flow and changes in the Early explorer Lieutenant James Grant named this fascinating remnant rock formation caused by heat volcano after a friend of his called Captain Schank. and steam. On the southern side The mountain differs from the craters in Mount Gambier in that its of the mountain, a small cone can floor is dry, being approximately at the level of the surrounding plain. be seen which is believed to have been formed by the first of two Evidence suggests two phases of volcanic activity. A small cone on the main stages. southern side of the mount was produced by the early phase, together with a basaltic lava flow to the west (the site of current quarrying • The Crater Floor Walk (1.3km operations). The later phase created the main cone, which now slightly return) also begins in the car park, overlaps the original smaller one and is known as a hybrid maar-cone and winds down to the crater floor structure. -

South Australia

2013 federal election Results Map South Australia N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Q U E E N S L A N D ! Marla A !Oodnadatta I N Innamincka ! L R A E GREY R T T S ! Coober Pedy S E S O U T H N U W A U S T R A L I A !Marree E A W ! ! ! Leigh Creek ! Cook ! Tarcoola S ! !Glendambo O ! Woomera U Nullarbor ! T H !Hawker Ceduna ! ! W Port Augusta Quorn ! A ! !Orroroo Streaky Bay Whyalla L ! Kimba ! !Peterborough Wudinna ! ! Port Pirie E Great Australian Bight S !Burra Clare ! Spencer ! Kadina Gulf Renmark 100 km ! ! ! Tumby Bay Berri Gawler ! Port Lincoln ADELAIDE Yorketown Gulf St West Point ! Vincent ! Murray Bridge Pinnaroo Cape Spencer ! V Kingscote ! Victor BARKER Harbor I Keith C Cape Gantheaume ! T ! Bordertown O Liberal Cape Jaffa !Kingston SE R Naracoorte! I A Division Boundary Penola ! Millicent ! Division Name Mount Gambier ! Cape Banks The electoral boundaries represented on this map are those in place at the 2013 federal election. 12_0100 Authorised by the Acting Electoral Commissioner, West Block Offices, Queen Victoria Terrace, Parkes, ACT. 2013 federal election Results Map Adelaide area and surrounds M A I N ! Clare N Y O W R H T H 20 km R E I! Saddleworth R R A B ! ! Balaklava Riverton Port Wakefield ! P O R T WAKEFIELD R D Kapunda W ! A r e K iv E R F IE L D D R Y t W Mallala Ligh H ! Freeling ! T R TU H S T R R D O N Gawler ! N I Williamstown A ! M ! Springton ! Elizabeth Birdwood ! ADELAIDE MAYO ! Summertown ! Woodside STH E AS T ERN GULF ST VINCENT Cape ! FW Jervis ! Mount Y Barker ! Callington Kangaroo Island ! Macclesfield Part of 50 km Mclaren MAYO ! Vale ! Strathalbyn ! Willunga ! Australian Labor Party Mount Compass Lake Normanville Alexandrina Liberal ! Division Boundary ! Goolwa ! Division Name Victor Harbor Cape Jervis The electoral boundaries represented on this map are those in place at the 2013 federal election. -

Pel 610 Pdf 1.3 Mb

INDEX OF DOCUMENTS HELD ON THE PUBLIC REGISTER FOR PETROLEUM EXPLORATION LICENCE PEL 610 1. 10 December 2012 Petroleum Exploration Licence PEL 610 granted Interests: Dunstone 100% Expiry Date: 9 December 2017 2. 10 December 2012 Memorandum entering PEL 610 on the public register. 3. 13 December 2012 Gazettal of grant of licence. 4. 11 December 2013 Memorandum entering amended description and map of licence area on the public register. 5. 5 November 2014 Surrender of licence with effect from 5 November 2014. 6. 5 November 2014 Memorandum entering surrender of licence on the public register. 7. 13 November 2014 Gazettal of surrender of licence. PEL 610.docx Page 1 of 1 6432 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE 13 November 2014 PETROLEUM AND GEOTHERMAL ENERGY ACT 2000 Surrender of Petroleum Exploration Licence—PEL 610 NOTICE is hereby given that I have accepted the surrender of the below mentioned petroleum exploration licence under the provisions of the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000, pursuant to delegated powers dated 21 March 2012. No. of Licence Licensee Date of Surrender Reference PEL 610 Dunstone 5 November 2014 F2012/000456 Dated 5 November 2014. N. PANAGOPOULOS, Acting Executive Director, Energy Resources Division, Department of State Development, Delegate of the Minister for Mineral Resources and Energy CULBURRA THE COORONG TINTINARA Ngarkat Conservation Park BUNNS SPRINGS V E I " 0 35° 56' 39" S 0 C MOUNT PENNY ' 5 0 ° T 0 4 1 KEITH O SC1998/004 MALLEE DOWNS R Gum Lagoon Mount Monster Conservation Park Conservation -

Kingston Se a P & H Society

KINGSTON SE A.P. & H. SOCIETY INC. MAJOR INFORMATION MAIN SHOW DAY – SUNDAY OCTOBER 6 ENTRY CLOSING DATES: August 30th Best Commercial Fleece Entries – see Wool Section September 27th Dressage & Horseman’s Challenge. October 3rd All Indoor, Livestock & Outdoor Sections and photographs delivered. October 4th All other wool to be delivered for judging – see Wool Section. ENTRIES will be taken in the old Wood Hut room (part of the District Hall), Agnes Street on September 26th (Thursday) & 27th (Friday), October 2nd (Wednesday) and 3rd (Thursday) - 10.00am to 4.00pm. ENTRIES WILL ALSO BE ACCEPTED BY THE FOLLOWING METHODS: Email: [email protected] Indoor: Post to Box 212, Kingston SE SA 5275 Phone: 0439000954 Outdoor: Box 96, Kingston SE SA 5275 Phone: 08 87672492 THURSDAY All photography to be deposited at the Wood Hut by 4.00pm on October 3rd. FRIDAY All wool other than Best Commercial Fleece to be delivered - see Wool Section. SATURDAY Art, Handicraft and Home Brew entries must be in the Football Clubrooms, and Woodwork in the Scout Hall by 11.00am on Saturday October 5th, as exhibits will be judged in the afternoon. SUNDAY - MAIN SHOW DAY Other indoor exhibits are to be in by 8.30am on Show Day, or be placed in the Football Clubrooms on Saturday from 9:30am. Wool and Farm Produce to the Pavilion by 8.30am on Sunday. Children’s Pets, Junior Show Personalities & Tiny Tots, Speed Shear Competition & Judging of the Outdoor and other Indoor Sections take place on the main day. TRADE SPACE We ask that Trade Spaces remain set up until 4.00 pm on Show Day Under cover: To be set up before 9.00am on Sunday October 6th. -

Work Services Regional Postcodes

For Official Use Only Return to work services Regional travel postcodes Effective date: 1 July 2018 Postcode Suburbs 0872 Ernabella 5116 Evanston, Evanston Gardens, Evanston Park, Evanston South, Hillier 5118 Bibaringa, Buchfelde, Concordia, Gawler, Gawler Belt, Gawler East, Gawler River, Gawler South, Gawler West, Hewett, Kalbeeba, Kangaroo Flat, Kingsford, Reid, Ward Belt, Willaston 5172 Dingabledinga, Hope Forest, Kuitpo, Kuitpo Colony, Kyeema, Montarra, Pages Flat, The Range, Whites Valley, Willunga, Willunga Hill, Willunga South, Yundi 5173 Aldinga, Aldinga Beach, Port Willunga, Silver Sands 5174 Sellicks Beach, Sellicks Hill 5202 Hindmarsh Tiers, Myponga, Myponga Beach 5203 Bald Hills, Parawa, Torrens Vale, Tunkalilla, Wattle Flat, Yankalilla 5204 Cape Jervis, Carrickalinga, Deep Creek, Delamere, Hay Flat, Normanville, Rapid Bay, Second Valley, Silverton, Wirrina Cove 5210 Mount Compass, Mount Magnificent, Nangkita 5211 Back Valley, Encounter Bay, Hayborough, Hindmarsh Valley, Inman Valley, Lower Inman Valley, Mccracken, Mount Jagged, Victor Harbor, Waitpinga, Willow Creek, Yilki 5212 Port Elliot 5213 Middleton 5214 Currency Creek, Goolwa, Goolwa Beach, Goolwa North, Goolwa South, Hindmarsh Island, Mosquito Hill, Mundoo Island 5220 Parndana 5221 American River, Ballast Head, Muston 5222 American Beach, Antechamber Bay, Baudin Beach, Browns Beach, Cuttlefish Bay, Dudley East, Dudley West, Hungerford, Ironstone, Island Beach, Kangaroo Head, Pelican Lagoon, Penneshaw, Porky Flat, Sapphiretown, Willoughby, Willson River 5223 Bay Of -

South Australia Suffolk Breeders 2019-20

SOUTH AUSTRALIA SUFFOLK BREEDERS 2019-20 Andrew & Judy Bates RMS 40 Butler Tanks, SA 5605 08 8688 0035 0427 880 035 [email protected] Prefix: SEATON PARK Flock No: 2046 Peter & Julie Button Box 103 Minlaton SA 5575 08 8853 2130 0419 842 246 [email protected] Prefix: RAMSAY PARK Flock No: 2211 Karen & Robert Cameron PO Box 96 Kingston SE SA 5275 08 8767 2492 0438 672 492 Prefix: NYRANG Flock No: 1770 Rachel Chirgwin Curlew Valley Suffolks PO Box 35 Saddleworth SA 5413 0428 600 265 [email protected] Prefix: CURLEW VALLEY Flock No: 2095 www.cvsuffolks.com.au Alastair Day & Sons 'Allendale' PO Box 10 Bordertown SA 5268 08 8752 1194 0429 782 711 [email protected] Prefix: ALLENDALE Flock No: 60 www.allendalestuds.com Anthony &Teresa Duffield 10 Howe Street Port Pirie SA 5540 (A)0429 676 610 (T)0438 184 724 [email protected] Prefix: BROUGHTON LODGE Flock No: 113 Mr/Ms SA & H Ellerby On The Lane Suffolk Stud PO Box 203 CRAFERS SA 5152 0432 549 404 [email protected] Prefix: LRBOTL Flock No: 2268 SOUTH AUSTRALIA SUFFOLK BREEDERS 2019-20 Anthony & Suzanne Ferguson 249 Ferguson Road Weetulta SA 5573 08 8835 2256 0417 759 958 [email protected] Prefix: ANNA VILLA Flock No: 653 Roland Floyd PO Box 213 Willunga SA 5172 0448 629 076 [email protected] Prefix: MAYDALE Flock No: 1653 Andrew & Tanya Frick C/- Post Office Padthaway SA 5271 08 8765 6005 0407 715 123 [email protected] Prefix: GYPSUM HILL Flock No: 943 Steve, Ros & Greg Funke PO Box 614 Bordertown SA 5268 08 8758 2032 0418 853 980 [email protected] Prefix: BUNDARA DOWNS Flock No: 2252 www.bundaradowns.com.au Jordan Galpin PO Box 385 Casterton Road Penola SA 5277 08 8737 2851 0409 108 708 [email protected] Prefix: WARRA – J Flock No: 2218 Cameron Grundy Pastoral Co.