Marching Song of the First Arkansas Colored Regiment: a Contested Attribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Rosa Parks Died in 2005, She Lay in Honor in the Rotunda of the Capitol, the First Woman and Only the Second Person of Color to Receive That Honor

>> When Rosa Parks died in 2005, she lay in honor in the Rotunda of the Capitol, the first woman and only the second person of color to receive that honor. When Congress commissioned a statue of her, it became the first full-length statue of an African American in the Capitol. It was unveiled on what would have been her 100th birthday. I sat down with some of my colleagues to talk about their personal memories of these events at the Capitol and the stories that they like to tell about Rosa Parks to visitors on tour. [ Music ] You're listening to "Shaping History: Women in Capitol Art" produced by the Capitol Visitor Center. Our mission is to inform, involve, and inspire every visitor to the United States Capitol. I'm your host, Janet Clemens. [ Music ] I'm here with my colleagues, and fellow visitor guides, Douglas Ike, Ronn Jackson, and Adriane Norman. Everyone, welcome to the podcast. >> Thank you. >> Thank you. >> Great to be here. >> Nice to be here. >> There are four of us around this table. I did some quick math, and this is representing 76 years of combined touring experience at the Capitol. And I'm the newbie here with only a decade [laughter]. Before we begin, I'm going to give my colleagues the opportunity to introduce themselves. >> I'm Douglas Ike, visitor guide here at the U.S. Capitol Building. I am approaching 17 years as a tour guide here at the Capitol. >> Adriane Norman, visitor guide, October 11, 1988, 32 years. >> Ronn Jackson, approaching 18 years. -

5Th Grade Learning Guide ELA

5th Grade Learning Guide ELA Note to Parents: The learning guides can be translated using your phone! How to Translate the Learning Guides: 1. Download the Google Translate app 2. Tap "Camera" 3. Point your camera at the text you want to translate 4. Tap "Scan" 5. Tap “Select all” ________________________________________________________________________________________ How to Use This Learning Guide: There are 3 core parts to this learning guide. First: Parents/students are provided with the text/story that can be read. ● In grades levels K-2, the text is found at the end of the learning guide. ● In grades levels 3 -5, the texts are found at the start of each lesson. Next: Parents/students are provided with an overview of what will be learned and are provided supports to help with learning (vocabulary, questions, videos, websites). ● Vocabulary words in bold are the most important for understanding the text. Finally: Parents/students are provided with the activities that can be completed using the text/story. ● Directions for the activities are provided and the directions for the choice board activities tell students how many tasks to complete. ● For choice boards, students should pick activities that interest them and that allow them to demonstrate what they have learned from the text/story. ● The Answer Key and Modifications Page are at the end of the Learning Guide to support your child. ● The Modifications Page includes Language Development resources for Newcomers. 1 Grade: 5 Subject: English Language Arts Topic: African American Suffragists by Margaret Gushue and Learning to Read by Francis Ellen Watkins Harper Access the text HERE and HERE or Embedded HERE What Your Student is Learning: Your student will read paired texts African American Suffragists and Learning to Read. -

Women's History Month, 2007

Proc. 8109 Title 3—The President We are grateful for the tireless work of the volunteers and staff of the American Red Cross. During this month, we pay tribute to this remarkable organization and all those who have answered the call to serve a cause greater than self and offered support and healing in times of need. NOW, THEREFORE, I, GEORGE W. BUSH, President of the United States of America and Honorary Chairman of the American Red Cross, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim March 2007 as American Red Cross Month. I commend the good work of the American Red Cross, and I encourage all Americans to help make our world a better place by volunteering their time, energy, and talents for others. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this twenty-seventh day of February, in the year of our Lord two thousand seven, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and thirty- first. GEORGE W. BUSH Proclamation 8109 of February 27, 2007 Women’s History Month, 2007 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation Throughout our history, the vision and determination of women have strengthened and transformed America. As we celebrate Women’s History Month, we recognize the vital contributions women have made to our country. The strong leadership of extraordinary women has altered our Nation’s his- tory. Sojourner Truth, Alice Stone Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe opened doors for future generations of women by advancing the cause of women’s voting rights and helping make America a more equitable place. -

Teacher Copy

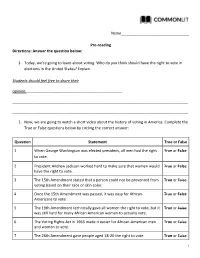

Name________________________________ Pre-reading Directions: Answer the question below: 1. Today, we’re going to learn about voting. Who do you think should have the right to vote in elections in the United States? Explain. Students should feel free to share their opinion._____________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ 2. Now, we are going to watch a short video about the history of voting in America. Complete the True or False questions below by circling the correct answer: Question Statement True or False 1 When George Washington was elected president, all men had the right True or False to vote. 2 President Andrew Jackson worked hard to make sure that women would True or False have the right to vote. 3 The 15th Amendment stated that a person could not be prevented from True or False voting based on their race or skin color. 4 Once the 15th Amendment was passed, it was easy for African- True or False Americans to vote. 5 The 19th Amendment technically gave all women the right to vote, but it True or False was still hard for many African American women to actually vote. 6 The Voting Rights Act in 1965 made it easier for African-American men True or False and women to vote. 7 The 26th Amendment gave people aged 18-20 the right to vote. True or False 1 2 3. Based on the video we just watched, how would you describe the history of voting in America? What groups of Americans have had to consistently fight for their right to vote? Answers will vary. -

Louisville Women and the Suffrage Movement 100 Years of the 19Th Amendment on the COVER: Kentucky Governor Edwin P

Louisville Women and the Suffrage Movement 100 Years of the 19th Amendment ON THE COVER: Kentucky Governor Edwin P. Morrow signing the 19th Amendment. Kentucky became the 23rd state to ratify the amendment. Library of Congress, Lot 5543 Credits: ©2020 Produced by Cave Hill Heritage Foundation in partnership with the Louisville Metro Office for Women, the League of Women Voters, Frazier History Museum, and Filson Historical Society Funding has been provided by Kentucky Humanities and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this program do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities or Kentucky Humanities. Writing/Editing: Writing for You (Soni Castleberry, Gayle Collins, Eva Stimson) Contributing Writers and Researchers: Carol Mattingly, Professor Emerita, University of Louisville Ann Taylor Allen, Professor Emerita, University of Louisville Alexandra A. Luken, Executive Assistant, Cave Hill Heritage Foundation Colleen M. Dietz, Bellarmine University, Cave Hill Cemetery research intern Design/Layout: Anne Walker Studio Drawings: ©2020 Jeremy Miller Note about the artwork: The pen-and-ink drawings are based on photos which varied in quality. Included are portraits of all the women whose photos we were able to locate. Suff•rage, sŭf’•rĭj, noun: the right or privilege of voting; franchise; the exercise of such a right; a vote given in deciding a controverted question or electing a person for an office or trust The Long Road to Voting Rights for Women In the mid-1800s, women and men came together to advocate for women’s rights, with voting or suffrage rights leading the list. -

Sojourner Truth at the “Mob Convention” 1853, New York City

Sojourner Truth at the “Mob Convention” 1853, New York City Sojourner Truth, a tall colored woman, well known in anti-slavery circles, and called the Lybian Sybil, made her appearance on the platform. This was the signal for a fresh outburst from the mob; for at every session every man of them was promptly in his place, at twenty-five cents a head. And this was the one redeeming feature of this mob—it paid all expenses, and left a surplus in the treasury. Sojourner combined in herself, as an individual, the two most hated elements of humanity. She was black, and she was a woman, and all the insults that could be cast upon color and sex were together hurled at her; but there she stood, calm and dignified, a grand, wise woman, who could neither read nor write, and yet with deep insight could penetrate the very soul of the universe about her. As soon as the terrible turmoil was in a measure quelled She said : Is it not good for me to come and draw forth a spirit, to see what kind of spirit people are of? I see that some of you have got the spirit of a goose, and some have got the spirit of a snake. I feel at home here. I come to you, citizens of New York, as I suppose you ought to be. I am a citizen of the State of New York; I was born in it, and I was a slave in the State of New York; and now I am a good citizen of this State. -

Return Always to Stillness, That Our Loving God Can Do What He Intends

Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ Partners in the work of the Spirit Volume 34, No. 4 Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ Winter 2013 Return always to stillness, that our loving God can do what he intends. — Blessed Catherine Kasper SOJOURNER TRUTH HOUSE New Board Member Reflects on Involvement with Sojourner Truth House A few months ago, I received Over the next few months, I received a very warm a Facebook message from a and personal introduction to STH. I attended a friend inquiring if I would “Coffee and Conversation” and was given a tour of be interested in serving on the facility. I even dropped by one day and had lunch the board of Sojourner Truth with the staff. I knew the organization did great House (STH). My mind work, but after chatting with some the clients, that’s immediately raced back to my when I began to pray that I would be appointed to previous encounters with the the board. I had to be a part of the solution! organization. I smiled when I thought of the Walk for STH Since being officially appointed to the board in and how it made me feel to August, I have rolled up my sleeves and gotten busy. join a sea of others walking to As Director of Communications for the City of Gary, Chelsea L. Whittington make a difference in the lives it is part of my job to coordinate charitable efforts of women and their children. and share these opportunities with city employees. We now have a monthly toiletry/food drive at City I then began to think…would I be able to meet the Hall where employees can bring in items all month commitment? I am the type of person who never and then they are delivered to STH at the end of the wants to do anything half way, so I wanted to be sure month. -

North Columbus Friends Meeting Woman's Suffrage Movement Time

North Columbus Friends Meeting Woman’s Suffrage Movement Time Line 1787: The US Constitutional Convention places voting qualifications in the hands of the state. Women in all states except New Jersey lose the right to vote. 1807: New Jersey revokes women’s right to vote. 1820: Elizabeth Margaret Chandler begins writing about women’s equality and was one of the earliest women Friends to speak out publicly against slavery. 1832: Chandler and Laura Smith Haviland, help to organize the Logan Female Anti-Slavery Society in Michigan. 1833: Lucretia Mott and others organized the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society 1837: First Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, held in New York City 1838: The second Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, held in Philadelphia 1840: Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton are barred from attending the World Anti- Slavery Convention held in London. This prompts them to hold a convention in the US 1848: The first women’s rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, NY. Women’s suffrage is proposed by Stanton and agreed to after an impassioned speech by Frederick Douglass. 1848: Elizabeth Cady Stanton writes “The Declaration of Sentiments,” creating the agenda of women’s activism for decades to come. 1850: The first National Woman’s Rights Convention is held in Worcester, Massachusetts, with more than 11,000 participants from 11 states. 1851: The second National Women’s Rights Convention, again in Worcester, Mass. 1851: At a women’s rights convention in Akron, Ohio, Sojourner Truth delivers her memorable speech, “Ain’t I a woman?” 1861-1865: During the Civil War, efforts for the suffrage movement are minimal. -

Rosa Parks and the Black Freedom Struggle in Detroit Downloaded From

Jeanne Theoharis “The northern promised land that wasn’t”: Rosa Parks and the Black Freedom Struggle in Detroit Downloaded from n 2004, researchers asked could stand to be pushed”—42- high school students across year-old Rosa Parks refused to give Ithe U.S. to name their top ten up her seat on the bus. This was “most famous Americans in his- not the first time she had resisted tory” (excluding presidents) from on the bus, and numerous other http://maghis.oxfordjournals.org/ “Columbus to the present day.” black Montgomerians had also Sixty percent listed Rosa Parks, who been evicted or arrested over the was second in frequency only to years for their resistance to bus Martin Luther King, Jr (1). There is segregation. For the next 381 days, perhaps no story of the civil rights faced with city intransigence, police movement more familiar to stu- harassment, and a growing White dents than Rosa Parks’ heroic 1955 Citizens’ Council, Rosa Parks, along- bus stand in Montgomery, Alabama side hundreds of other Montgomeri- and the year-long boycott that ans, worked tirelessly to maintain ensued. And yet, perhaps because the boycott. On December 20, 1956, at University of Birmingham on August 24, 2015 of its fame, few histories are more with the Supreme Court’s decision mythologized. In the fable, racial outlawing bus segregation, Mont- injustice was rampant in the South gomery’s buses were desegregated. (but not the rest of the nation). A Yet the story is even more quiet seamstress tired from a day’s multi-dimensional than previously work without thought refused to recognized. -

The Carter G. Woodson Book Awards

Social Education 69(4), pp. 199-200 © 2005 National Council for the Social Studies The Carter G. Woodson Book Awards National Council for the Social Studies has 2004 Carter G. Woodson Award Book: Elementary Level sponsored the Carter G. Woodson Book Sacagawea, by Lise Erdrich, illustrated by Julie Buffalohead. Minneapolis, Minn.: Awards for more than 30 years. The idea Carolrhoda Books, Inc., a division of Lerner Publishing Group. evolved out of the Committee on Racism and Reviewed by Barbara Stanley, assistant professor, Department of Middle Grades and Secondary Social Justice in 1973 and has since grown Education at Valdosta State University, Valdosta, Georgia. into a nationally recognized children’s Lise Erdrich’s Sacagawea offers a vibrantly illustrated, detailed narrative about nonfiction book award, prized by many a woman who had a significant impact on the exploration of the American West. authors and publishers. The story begins when Hidatsa warriors capture a young Sacagawea from her The award was created and named Shoshone tribe. to honor Carter G. Woodson, the distin- The Hidatsa people gave her the name Sacagawea, meaning, “bird woman.” guished African American writer, scholar, They taught her the ways of cultivation, as practiced by their permanent settle- and educator. Woodson, often regarded ments; the Shoshone, on the other hand, were gatherers. When she was 16, her as the “father of Negro history,” was the husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, was contracted to guide members of the second African American to receive a doc- Corps of Discovery, led by Captain Meriwether Lewis and Captain William Clark. torate from Harvard University. In 1926, Sacagawea and her infant Pomp traveled with the party. -

Congressional Record—Senate S892

S892 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE February 28, 2000 paragraph (11), by striking the period at the ondary school' have the meanings given such ization request for fiscal year 2001 and end of paragraph (12) and inserting ``, and'', terms by section 14101 of the Elementary and the future years defense program. and by adding at the end the following new Secondary Education Act of 1965 (20 U.S.C. The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without paragraph: 8801), as so in effect.''. objection, it is so ordered. ``(13) any deduction allowable for the quali- (b) EFFECTIVE DATE.ÐThe amendments fied professional development expenses paid made by this section shall apply to taxable COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES or incurred by an eligible teacher.''. years beginning after December 31, 2000. Mr. THOMAS. Mr. President, I ask (b) DEFINITIONS.ÐSection 67 (relating to 2- f unanimous consent that the Com- percent floor on miscellaneous itemized de- mittee on Armed Services be author- ductions) is amended by adding at the end NOTICES OF HEARINGS the following new subsection: ized to meet during the session of the ``(g) QUALIFIED PROFESSIONAL DEVELOP- COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION, AND Senate on Monday, February 28, 2000, MENT EXPENSES OF ELIGIBLE TEACHERS.ÐFor FORESTRY at 4 p.m., in open session to receive tes- purposes of subsection (b)(13)Ð Mr. LUGAR. Mr. President, I would timony on the national security impli- ``(1) QUALIFIED PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT like to announce that the Senate Com- cations of export controls and to exam- EXPENSES.Ð mittee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and ine S. 1712, the Export Administration ``(A) IN GENERAL.ÐThe term `qualified pro- fessional development expenses' means Forestry will meet on March 1, 2000, in Act of 1999. -

AVAILABLE Fromnational Women's History Week Project, Women's Support Network, Inc., P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 233 918 SO 014 593 TITLE Women's History Lesson Plan Sets. INSTITUTION Women's Support Network, Inc., Santa Rosa, CA. SPONS AGENCY Women's Educational Equity Act Program (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 83 NOTE 52p.; Prepared by the National Women's History Week Project. Marginally legible becalr,:e of colored pages and small print type. AVAILABLE FROMNational Women's History Week Project, Women's Support Network, Inc., P.O. Box 3716, Santa Rosa, CA 95402 ($8.00). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Art Educatien; Audiovisual Aids; Books; Elementary Secondary Education; *English Instruction; *Females; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; Lesson Plans; Models; Resource Materials; Sex Role; *United States History; *Womens Studies IDENTIFIERS Chronology; National Womens History Week Project ABSTRACT The materials offer concrete examples of how women contributed to U.S. history during three time periods: 1763-1786; 1835-1860; and 1907-1930. They can be used as the basis for an interdisciplinary K-12 program in social studies, English, and art. There are three major sections to the guide. The first section suggests lesson plans for each of the time periods under study. Lesson plans contain many varied learning activities. For example, students read and discuss books, view films, do library research, sing songs, study the art of quilt making, write journal entries of an imaginary trip west as young women, write speeches, and research the art of North American women. The second section contains a chronology outlining women's contributions to various events.