T-1683-18 Citation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ClosingCanada'sDigitalDivide: AReview Of

CLOSING CANADA’S DIGITAL DIVIDE: A REVIEW OF POLICIES IN CANADA AND ABROAD by Charlie Crabb A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Digital Media In the Yeates School of Graduate Studies Ryerson University Toronto, Ontario, Canada © Charlie Crabb, 2017 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this MRP. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. 1 Abstract This paper explores Canada’s telecommunications policy landscape, with an aim of evaluating its -

An Introduction to Telecommunications Policy in Canada

Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy An Introduction to Telecommunications Policy in Canada Catherine Middleton Ryerson University Abstract: This paper provides an introduction to telecommunications policy in Canada, outlining the regulatory and legislative environment governing the provision of telecommunications services in the country and describing basic characteristics of its retail telecommunications services market. It was written in 2017 as one in a series of papers describing international telecommunications policies and markets published in the Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy in 2016 and 2017. Drawing primarily from regulatory and policy documents, the discussion focuses on broad trends, central policy objectives and major players involved in building and operating Canada’s telecommunications infrastructure. The paper is descriptive rather than evaluative, and does not offer an exhaustive discussion of all telecommunications policy issues, markets and providers in Canada. Keywords: Policy; Telecommunications; Canada Introduction In 2017, Canada’s population was estimated to be above 36.5 million people (Statistics Canada, 2017). Although Canada has a large land mass and low population density, more than 80% of Canadiansi live in urban areas, the majority in close proximity to the border with the United States (Central Intelligence Agency, 2017). Telecommunications services are easily accessible for most, but not all, Canadians. Those in lower-income brackets and/or living in rural and remote areas are less likely to subscribe to telecommunications services than people in urban areas or with higher incomes, and high-quality mobile and Internet services are simply not available in some parts of the country (CRTC, 2017a). On average, Canadian households spend more than $200 (CAD)ii per month to access mobile phone, Internet, television and landline phone services (2015 data, cited in CRTC, 2017a). -

Data Privacy Transparency of Canadian Internet Carriers

Keeping Internet Users in the Know or in the Dark A Report on the Data Privacy Transparency of Canadian Internet Carriers Andrew Clement* & Jonathan A. Obar** [email protected]. [email protected] IXmaps.ca & New Transparency Projects *Faculty of Information, University of Toronto **Faculty of Social Science and Humanities, University of Ontario Institute of Technology in collaboration with the Centre for Innovation Law and Policy (CILP), Faculty of Law, University of Toronto March 12, 2015 Acknowledgements We appreciate the contributions of our research collaborators and assistants at the University of Toronto: Antonio Gamba, Alex Goel and Colin McCann. We are also pleased to acknowledge the input of Steve Anderson, (Openmedia.ca), Nate Cardozo (EFF), Andrew Hilts (Cyber Stewards Initiative), Tamir Israel (CIPPIC) and Christopher Parsons (Citizen Lab). The research reported here benefited significantly from collaboration with the Centre for Innovation Law and Policy (CILP), Faculty of Law, University of Toronto. We worked most closely with Matthew Schuman, Assistant Director, and Ainslie Keith, who led a Volunteer Student Working Group consisting of Shawn Arksey, Michael Cockburn, Caroline Garel- Jones, Aaron Goldstein, Nathaniel Rattansey, Kassandra Shortt, Jada Tellier and Matthew Vaughan. Website and report design assistance: Jennette Weber This research was conducted under the auspices of the IXmaps: Mapping Canadian privacy risks in the internet ‘cloud’ project (see IXmaps.ca) and the Information Policy Research Program (IPRP), with the support of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (2012-13), The New Transparency: Surveillance and Social Sorting project funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (2012-15), and the Mapping Canadian internet traffic, infrastructure and service provision (2014-15), funded by the Canadian Internet Registration Authority (CIRA). -

Canadian Telecommunications Services

RBC Dominion Securities Inc. Drew McReynolds, CFA, Caleb Ho, CPA, CFA CA, CPA (Analyst) (Associate) (416) 842-3805 (416) 842-3806 [email protected] [email protected] Riley Gray (Associate) (416) 842-4123 [email protected] August 31, 2020 Canadian Telecommunications Services August Channel Checks and Market Developments We summarize notable market developments within the Canadian telecommunications sector since July. For more detail on sector trends, please see our August 21, 2020 report entitled "Q2/20 Review - Wireless Competitive Intensity in Focus (Again)". EQUITY RESEARCH Notable sequential pick-up in promotional activity with what appears to be less back-to- school fanfare We observed a healthy dose of main brand promotional activity in August focused on the 20GB data bucket that was largely characterized by handset and plan pricing discounts, alongside what appears to be less YoY back-to-school promotional activity. On a sequential basis, promotional activity not surprisingly stepped up in August driven by incumbent responses to the launch of Shaw Mobile last month. Notably: (i) the iPhone 11 was offered on discount (~$520 off) by incumbent operators on refurbishing unlimited plans; (ii) in mid-August, while pricing on the promotional $80/20GB unlimited plans was momentarily increased to $85/20GB, $75/20GB pricing was re-introduced by all incumbents with this pricing remaining in-market through the end of August; (iii) in mid-August, TELUS launched a ‘Great Big Sale’ offering the aforementioned $75/20GB “Peace of Mind” -

Canada Sets World Record for Prices of Mid-Band Spectrum Licenses

Canada Sets World Record for Prices of Mid-Band Spectrum Licenses 3500 MHz Auction Results – August 2021 An LYA® ® c-Ahead Report © LYA, 2021 Ò Canada Sets World Record for Prices of Mid-Band Spectrum Licenses 3500 MHz Auction Results August 2, 2021 – Canada’s recently completed auction of 3.5 GHz licenses – results announced July 29, 2021 – blasted through the previous high-water market for mid- band spectrum licenses. The total of C$8.91 billion (US$7.13 billion) in revenues for an average of 125 MHz per market in the 3450-3650 MHz range represents a record C$2.26 per MHz-pop or US$1.81… essentially double the valuations seen on average in the US C Band auction held earlier in 2021, and close to 10x the averages seen in earlier auctions. Canada is often viewed as a country with relatively high retail prices for mobile services. High prices for spectrum paid in auctions may ultimately flow to consumers helping to keep prices high in the future. We discuss herein some of the causes of these prices pertaining to auction rules and dynamics. LYA c-Ahead Report – Canadian 3500 MHz Spectrum License Auction Reproduction or dissemination of this Report in whole or in part is strictly prohibited – all rights reserved. Permission from LYA is required to quote or excerpt any part of this Report. © LYA, 2021 Page 1 Ò We also note how CRTC became a “player” in this auction via the awkward or inappropriate timing of the release of two major decisions impacting telecom carriers across the country. -

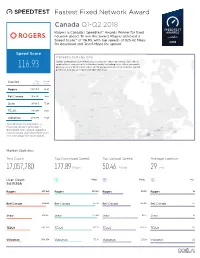

Fastest Fixed Network Award Canada Q1-Q2 2018 Rogers Is Canada’S Speedtest® Awards Winner for Fixed Network Speed

Fastest Fixed Network Award Canada Q1-Q2 2018 Rogers is Canada’s Speedtest® Awards Winner for fixed network speed. To win this award, Rogers achieved a Speed Score™ of 116.93, with top speeds of 325.42 Mbps for download and 30.05 Mbps for upload. Speed Score Canada’s Tests by City Ookla® compared user-initiated tests that are taken on various Speedtest applications connected to a fixed network, including tests taken on mobile 116.93 phones over a Wi-Fi connection. All major provider results from the award period in Canada are represented in the map. Test Speed Carrier Count Score Rogers 3,874,719 116.93 Bell Canada 2,918,367 74.53 Shaw 1,974,613 73.28 TELUS 1,763,951 59.53 Videotron 1,185,988 49.27 Speed Score incorporates a measure of each provider’s download and upload speed to rank network speed performance. See next page for more detail. Market Statistics Test Count Top Download Speed: Top Upload Speed: Average Latency: 17,057,780 177.89 Mbps 50.46 Mbps 29 ms User Count Mbps Mbps ms 9,619,868 Rogers 835,941 Rogers 325.42 Rogers 30.05 Rogers 19 Bell Canada 762,096 Bell Canada 237.13 Bell Canada 125.68 Bell Canada 23 Shaw 501,037 Shaw 172.40 Shaw 16.32 Shaw 18 TELUS 454,749 TELUS 167.12 TELUS 149.22 TELUS 20 Videotron 306,938 Videotron 135.16 Videotron 23.99 Videotron 22 Fastest Fixed Network Award Canada Q1-Q2 2018 How Speed Score Works When analyzing fastest operators, Ookla solely considers top carriers (all carriers with 3% or more of total test samples in the market for the period). -

Ear Falls Broadband Study

Broadband Study TOWNSHIP OF EAR FALLS January 2021 Copyright 2021 All Rights Reserved. Township of Ear Falls CONTACT INFORMATION Township of Ear Falls P.O. Box 309 2 Willow Crescent Ear Falls, ON P0V 1T0 REPORT COMPLETED BY: REPORT SUPPORTED BY: AMEDEO BERNARDI CONSULTING INC. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 4 2. Approach to the Study ........................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Scope of Work ........................................................................................................................... 5 3. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 4. Broadband Primer .................................................................................................................. 8 4.1 What is broadband? .................................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Global Network ....................................................................................................................... 18 4.3 Canadian Network ................................................................................................................... 20 4.4 National Transport .................................................................................................................. 20 4.5 -

Nunavut's Telecom Network May Face a Meltdown from Overuse, ISP Warns

5/26/2020 Nunavut’s telecom network may face a meltdown from overuse, ISP warns | Nunatsiaq News IQALUIT KUUJJUAQ 0° -9° mostly cloudy partly cloudy TUESDAY, 26 MAY, 2020 JOBS TENDERS NOTICES ADVERTISE ABOUT US CONTACT PDF EDITION E-EDITION NEWS FEATURES EDITORIAL LETTERS OPINION TAISSUMANI ARCHIVES NEWS 24 MARCH 2020 – 10:30 AM EDT Nunavut’s telecom network may face a meltdown from overuse, ISP warns Northwestel did not need CRTC permission to double Nunavut bandwidth caps Workers at SSi Micro’s teleport in Kanata, Ont., where the Nunavut-wide Qiniq network is managed. (File photo) By Jim Bell https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/nunavuts-telecom-network-may-face-a-meltdown-from-overuse-isp-warns/ 1/14 5/26/2020 Nunavut’s telecom network may face a meltdown from overuse, ISP warns | Nunatsiaq News If you live in Nunavut and you’re stuck at home until who knows when, try not to hog the available internet bandwidth. SSi Micro, operator of the Qiniq network that provides internet and mobile phone service to all 25 Nunavut communities, issued that advice last week, warning that from now on, the territory’s satellite telecom services could suöer crippling traõc jams that could hurt all users. That’s because of the large numbers of people who have been told to stay put in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including children and youth who can’t go to school, and workers who have been asked to do their jobs from home. “There’s only so much backbone available. It’s a ùnite amount. -

Xplornet Communications Inc. ______

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada Spectrum Management and Telecommunications As published in Canada Gazette, Part 1, Vol. 153, No. 25 on June 22, 2019 Notice No. SLPB-002-19 Consultation on a Policy and Licensing Framework for Spectrum in the 3500 MHz Band ______________________________________________ Reply Comments of Xplornet Communications Inc. ______________________________________________ September 20, 2019 Xplornet Communications Inc. Consultation on Policy and Licensing Framework for Spectrum in the 3500 MHz Band (Notice No. SLPB-002-19) – Reply Comments EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Xplornet Communications Inc. (“Xplornet”) has had the opportunity to review comments filed by parties with respect to the Consultation on a Licensing and Policy Framework for Spectrum in the 3500 MHz Band (“Consultation”) currently being undertaken by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (“ISED”) and is pleased to provide the present reply comments. 2. In designing the present auction, ISED is faced with the task of developing a framework that will ensure that the spectrum in the 3500 MHz band (“3500 MHz spectrum”) is allocated to provide maximum economic and social benefits to Canadians, as required by Spectrum Policy Framework for Canada1 (“Spectrum Policy Framework”). ISED is assisted in this process by directions set out in the enabling guidelines of the Spectrum Policy Framework. 3. Following the directions of the enabling guidelines, we submit that ISED’s design for the present auction should consider the following themes: - The auction should address and balance the interests of all Canadians in new 5G services; - The auction should promote technological innovation in rural and urban areas; and - The auction should be inclusive in order to promote the competition needed to maximize the above goals. -

Leading the World When the World Needs Us Most

Leading the world when the world needs us most ANNUAL REPORT 2020 We are leading the world TELUS is a dynamic, world-leading communications 1–9 technology company with $16 billion in annual revenue Corporate overview and 16 million customer connections spanning wireless, data, IP, voice, television, entertainment, video and Supporting our stakeholders through an unprecedented year, results and highlights security. We leverage our global-leading technology from 2020, and our 2021 targets and compassion to enable remarkable human outcomes. Our long-standing commitment to putting our customers first fuels every aspect of our business, 10–15 making us a distinct leader in customer service CEO letter to investors excellence and loyalty. TELUS Health is Canada’s Keeping our stakeholders connected to leader in digital health technology, TELUS Agriculture what matters most through our leadership in social capitalism provides innovative digital solutions throughout the agriculture value chain and TELUS International is a leading digital customer experience innovator 16–17 that delivers next-generation AI and content Our social purpose at a glance management solutions for global brands. Leveraging technology to enable remarkable human outcomes Driven by our passionate social purpose to connect all citizens for good, our deeply meaningful and 18 –21 enduring philosophy to give where we live has inspired Operations at a glance TELUS, our team members and retirees to contribute Reviewing our wireless and wireline more than $820 million and 1.6 million days of operations service since 2000. This unprecedented generosity and unparalleled volunteerism have made TELUS the most giving company in the world. 22– 29 Leadership Our Executive Team, questions and answers, Many photos within this report were taken Board of Directors and corporate governance prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. -

BCE 2020 Annual Report

IN TWENTY-TWENTY WE WERE AT THE OF CONNECTIONS WHEN IT MATTERED MOST. ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Advancing how Canadians connect with each other and the world OUR FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE Stepping up in a year like no other As the Bell team kept Canada connected in a challenging 2020, we built marketplace momentum with world-class network, service and content innovations for our customers while delivering sustainable dividend growth for our shareholders. 2020 financial performance Revenue * (3.8%) Adjusted EBITDA (1) * (4.0%) Capital intensity 18.4% Adjusted EPS (1) $3.02 Free cash flow (1) * (10.4%) * Compared to 2019 6.1 % +307% Dividend yield Total shareholder in 2020 (2) return 2009–2020 (3) +5.1 % +140% Increase in dividend Increase in dividend per common share per common share for 2021 2009–2021 (1) Adjusted EBITDA, adjusted EPS and free cash floware non-GAAP financial measures and do not have any standardized meaning under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Therefore, they are unlikely to be comparable to similar measures presented by other issuers. For a full description of these measures, see section 10.2, Non-GAAP financial measures and key performance indicators (KPIs) on pp. 115 to 117 of the MD&A. (2) Annualized dividend per BCE common share divided by BCE’s share price at the end of the year. (3) The change in BCE’s common share price for a specified period plus BCE common share dividends reinvested, divided by BCE’s common share price at the beginning of the period. 2 | BCE INC. 2020 AnnuAL REPORT OUR PURPOSE Bell’s goal and Strategic Imperatives Our goal is to advance how Canadians connect with each other and the world, and the Bell team is executing a clear strategy that leverages our strengths and highlights the opportunities of the broadband economy for our company and all our stakeholders. -

Canada's Counter-Memorial on Merits and Damages

Public Version IN THE MATTER OF AN ARBITRATION UNDER THE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FOR THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF INVESTMENTS AND THE ICSID CONVENTION BETWEEN: GLOBAL TELECOM HOLDING S.A.E. Claimant AND GOVERNMENT OF CANADA Respondent GOVERNMENT OF CANADA COUNTER-MEMORIAL ON MERITS & DAMAGES February 26, 2018 Trade Law Bureau Government of Canada Lester B. Pearson Building 125 Sussex Drive Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G2 CANADA Public Version TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS ......................................................................................... VIII CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS ......................................................................................... XVI INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................... 1 I. Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 II. Materials Submitted by Canada....................................................................................... 11 FACTS ..................................................................................................................................... 11 I. Regulation of Wireless Telecommunications in Canada................................................. 11 A. The Relevant Regulatory Bodies and Their Roles ................................................. 11 B. Objectives of Canada’s Telecommunications Policy and