Armenian Genocide Art As Evidence of Its Existence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Armenian Genocide

The Armenian Genocide During World War I, the Ottoman Empire carried out what most international experts and historians have concluded was one of the largest genocides in the world's history, slaughtering huge portions of its minority Armenian population. In all, over 1 million Armenians were put to death. To this day, Turkey denies the genocidal intent of these mass murders. My sense is that Armenians are suffering from what I would call incomplete mourning, and they can't complete that mourning process until their tragedy, their wounds are recognized by the descendants of the people who perpetrated it. People want to know what really happened. We are fed up with all these stories-- denial stories, and propaganda, and so on. Really the new generation want to know what happened 1915. How is it possible for a massacre of such epic proportions to take place? Why did it happen? And why has it remained one of the greatest untold stories of the 20th century? This film is made possible by contributions from John and Judy Bedrosian, the Avenessians Family Foundation, the Lincy Foundation, the Manoogian Simone Foundation, and the following. And others. A complete list is available from PBS. The Armenians. There are between six and seven million alive today, and less than half live in the Republic of Armenia, a small country south of Georgia and north of Iran. The rest live around the world in countries such as the US, Russia, France, Lebanon, and Syria. They're an ancient people who originally came from Anatolia some 2,500 years ago. -

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Yektan Turkyilmaz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the conflict in Eastern Anatolia in the early 20th century and the memory politics around it. It shows how discourses of victimhood have been engines of grievance that power the politics of fear, hatred and competing, exclusionary -

Machine Age Humanitarianism”: American Humanitarianism in Early-20Th Century Syria and Lebanon

chapter 8 “Machine Age Humanitarianism”: American Humanitarianism in Early-20th Century Syria and Lebanon Idir Ouahes Historians of humanitarianism have increasingly scrutinized its social and political perspectives in the hope of defining a unitary field of study. One trend has sought to emphasize the pre-existing contexts prior to the formalization of humanitarian activity.1 Other accounts, such as Michael Barnett’s, suggest that humanitarianism as a concept should be considered separately from tra- ditional charity since it is a particularly modern, Western phenomenon that emerged from Enlightenment ethics (transcendentalism and universalism).2 In the Middle Eastern context, Ottoman-era massacres have generated the most attention.3 Historians of the Middle East have nevertheless also sought to emphasize the well-established Islamic charitable experience. Islamic awqāf (mortmain perpetuities) have been an intrinsic part of the region’s human- itarian activity.4 These Islamic financial instruments provided for a range of charitable activities, even for the protection of birds as was the case in a Fezzan waqf. 1 Peter Stamatov, The Origins of Global Humanitarianism: Religions, Empires, and Advocacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). Stamatov and earlier historian Frank Kling- berg nevertheless recognize the importance of the slavery abolitionists in giving impetus to humanitarianism and forging the domestic welfare state. See Stamatov, The Origins, 155–172; Frank J. Klingberg, “The Evolution of the Humanitarian Spirit in Eighteenth-Century Eng- land,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 66, no. 3 (July 1942): 260–278. David Forsythe notes the parallels between Henry Dunant’s International Committee of the Red Cross, set up in 1859, and London’s Anti-Slavery Society, founded in 1839. -

Armenian Genocide

JULY 2015 ARMENIAN GENOCIDE FOURTEENTH ASSEMBLY, UNITING CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA RESOLUTION 15.23.01 An Overview 15.23.01 The Assembly resolved to: a. acknowledge that the Armenian massacres and forced deportations of 1915-1923 constitute a Geno- cide; b. commend the NSW and SA governments in acknowledging the Armenian Genocide and encourage the Federal and other state governments to do the same; and c. affirm the value of recognising a date on or near the anniversary of the Armenian genocide, as a day of observance and commemoration of the Armenian Genocide and request the National Consultant Christian Unity, Doctrine and Worship to prepare: i. prayer to be provided for all congregations of the UCA for use on the day; and ii. in consultation with others, educational and liturgical resources for congregations to use. Rationale The Oxford Dictionary defines genocide as “the deliberate killing of a very large number of people from a particular ethnic group or nation.” An outline of the Armenians and the Armenian genocide follows. The Legend of the origins of Armenians goes back to Noah. The Legend has it that Hayk, the ancestor of the Armenians is the son of Torgom son of Tiras son of Gomer son of Japheth son of Noah. Hayk had an argu- ment with Belus (Bel) and migrated with his group from Babylon to the North and settled in what became Armenia. The Land they settled in included current day Armenia, Nagorno Karabakh, Nakhichevan, parts of north-western Syria, part of south-western Georgia and the eastern half of Turkey. In 301 C.E., Armenia became the first Christian nation. -

Sabiha Gökçen's 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ―Sabiha Gökçen‘s 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation Formation and the Ottoman Armenians A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Fatma Ulgen Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Hasan Kayalı Copyright Fatma Ulgen, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Fatma Ulgen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For my mother and father, without whom there would be no life, no love, no light, and for Hrant Dink (15 September 1954 - 19 January 2007 iv EPIGRAPH ―In the summertime, we would go on the roof…Sit there and look at the stars…You could reach the stars there…Over here, you can‘t.‖ Haydanus Peterson, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, reminiscing about the old country [Moush, Turkey] in Fresno, California 72 years later. Courtesy of the Zoryan Institute Oral History Archive v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………….... -

Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism During the Armenian Genocide

Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University Author Note: Elizabeth N. Call, Public Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York; Matthew Baker, Collection Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Elizabeth Call The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary 3041 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Contact: [email protected] Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 7 Abstract American Protestant missionaries played important political and cultural roles in the late Ottoman Empire in the period before, during, and after the Armenian genocide. They reported on events as they unfolded and were instrumental coordinating and executing relief efforts by Western governments and charities. The Burke Library’s Missionary Research Library, along with several other important collections at Columbia and other nearby research repositories, holds a uniquely rich and comprehensive body of primary and secondary source materials for understanding the genocide through the lens of the missionaries’ attempts to document and respond to the massacres. Keywords: Armenian genocide, Turkey, missionaries, Near East, WWI, Middle East Christianity Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 8 Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University April 2015 marks the centenary of the beginning of the Armenian genocide, in which an estimated 1 to 1.5 million members of the indigenous and ancient Christian minority in what is now eastern Turkey, along with many co-religionists from the Assyrian and Greek Orthodox communities, perished through forced deportation or execution (Kevorkian, 2011). -

Armenian Genocide

Armenian Genocide Where Armenians predominantly lived in the Ottoman Empire Who are the Armenians? • In 301 AD, Armenia became the first official Christian nation in the world • the Armenians were the largest Christian minority in the Ottoman Empire with a population of 2 million – constituted a Christian "island" in a mostly Muslim region • Armenians began demanding independence following the Russo-Turkish War of 1878 – Armenians in the Ottoman Empire were promised rights under the Treaty of Berlin, but never saw them – Led to the formation of Armenian revolutionary groups The disintegration of the Ottoman Empire The disintegration of the Ottoman Empire ● In 1832, Greece had broken free of Ottoman rule ● In 1876 Serbia and Montenegro fought for their independence along with Bosnia and Herzegovina. ● In 1877 Bulgaria also rebelled Sultan Abdul Hamid II • Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (1876-1908) • Fiercely nationalistic • dismissed the parliament and overturned all Western reforms – resisted the pressures of the European powers – Looked at himself as the champion of Islam against aggressive Christianity • Groups of Christians started to protest their loss of rights and persecution Armenian Massacres • In 1896, a group of Armenian revolutionaries raided the headquarters of the Ottoman Bank in Istanbul – Guards were shot and more than 140 staff members were taken hostage - all in an attempt to gain international attention for the plight of Armenians • In response, tens of thousands of Armenians were massacred – The Sultan’s personal cavalry -- the Hamidiye – carried out the massacres – The worst atrocity occurred when the Cathedral of Urfa, in which 3,000 Armenians had taken refuge, was burned – Massacres lasted from 1894-1896 • killed 200,000 Armenians • Known as the Hamidian Massacres Hamidiye This is a sketch by an eye-witness of the massacre of Armenians by Turkish soldiers in the Ottoman Empire A hanged Armenian in Constantinople (Aug. -

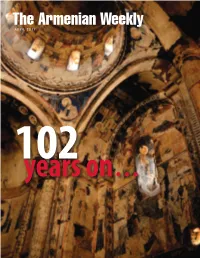

Here Is Another Accounting Due

The Armenian Weekly APRIL 2017 102years on . The Armenian Weekly NOTES REPORT 4 Contributors 19 Building Bridges in Western Armenia 5 Editor’s Desk —By Matthew Karanian COMMENTARY ARTS & LITERATURE 7 ‘The Ottoman Lieutenant’: Another Denialist 23 Hudavendigar—By Gaye Ozpinar ‘Water Diviner’— By Vicken Babkenian and Dr. Panayiotis Diamadis RESEARCH REFLECTION 25 Diaspora Focus: Lebanon—By Hagop Toghramadjian 9 ‘Who in this room is familiar with the Armenian OP-ED Genocide?’—By Perry Giuseppe Rizopoulos 33 Before We Talk about Armenian Genocide Reparations, HISTORY There is Another Accounting Due . —By Henry C. Theriault, Ph.D. 14 Honoring Balaban Hoja: A Hero for Armenian Orphans 41 Commemorating an Ongoing Genocide as an Event —By Dr. Meliné Karakashian of the Past . —By Tatul Sonentz-Papazian 43 The Changing Significance of April 24— By Michael G. Mensoian ON THE COVER: Interior of the Church of St. Gregory of Tigran 49 Collective Calls for Justice in the Face of Denial and Honents in Ani (Photo: Rupen Janbazian) Despotism—By Raffi Sarkissian The Armenian Weekly The Armenian Weekly ENGLISH SECTION THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY The opinions expressed in this April 2017 Editor: Rupen Janbazian (ISSN 0004-2374) newspaper, other than in the editorial column, do not Proofreader: Nayiri Arzoumanian is published weekly by the Hairenik Association, Inc., necessarily reflect the views of Art Director: Gina Poirier 80 Bigelow Ave, THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY. Watertown, MA 02472. ARMENIAN SECTION Manager: Armen Khachatourian Sales Manager: Zovig Kojanian USPS identification statement Editor: Zaven Torikian Periodical postage paid in 546-180 TEL: 617-926-3974 Proofreader: Garbis Zerdelian Boston, MA and additional FAX: 617-926-1750 Armenian mailing offices. -

Secret Armies and Revolutionary Federations: the Rise and Fall of Armenian Political Violence, 1973-1993 Christopher Gunn

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Secret Armies and Revolutionary Federations: The Rise and Fall of Armenian Political Violence, 1973-1993 Christopher Gunn Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES SECRET ARMIES AND REVOLUTIONARY FEDERATIONS: THE RISE AND FALL OF ARMENIAN POLITICAL VIOLENCE, 1973-1993 By CHRISTOPHER GUNN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2014 Christopher Gunn defended this dissertation on July 8, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jonathan Grant Professor Directing Dissertation Mark Souva University Representative Michael Creswell Committee Member Will Hanley Committee Member Edward Wynot Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To Felix and Maxim iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Over the last eight years, I have become indebted to a number of individuals and organizations that helped, assisted, and encouraged me as I pursued my doctorate in history and this research project in particular. Without them, I would never have completed this journey. I owe a special thanks to the late Daniel Walbolt, and his spouse, Sylvia, who have generously supported the Department of History at Florida State University, and who provided the means for my fellowship at the University. I am extremely grateful for the patience and guidance of my advisor, Dr. -

Becoming Armenian: Religious Conversions in the Late Imperial South Caucasus

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(1):242–272. 0010-4175/21 # The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:10.1017/S0010417520000432 Becoming Armenian: Religious Conversions in the Late Imperial South Caucasus VLADIMIR HAMED-TROYANSKY University of California, Santa Barbara INTRODUCTION In 1872, Russian authorities in the Caucasus received a petition from a Muslim Kurdish family in Novobayazetsky Uezd, a district around Lake Sevan in modern-day Armenia. Four brothers, Mgo, Avdo, Alo, and Fero, and their mother Gapeh requested the government to allow them to leave Islam and convert to the Armenian Apostolic faith.1 They added testimonies of their fellow Armenian neighbors, who confirmed that these Kurdish residents of the snowy highlands in the south of the Russian Empire were genuine in their desire to accept Christianity. Russian officials in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, Georgia), the capital of the Caucasus Viceroyalty, were perplexed but not surprised by such a request. In the late tsarist era, hundreds of individuals and families living in the South Caucasus asked to change their faith. -

Downloaded on February 19, 2007 (

CHOOSING SILENCE: THE UNITED STATES, TURKEY AND THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE by Maral N. Attallah A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Sociology May, 2007 CHOOSING SILENCE: THE UNITED STATES, TURKEY AND THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE by Maral N. Attallah Approved by the Master’s Thesis Committee: ________________________________________________________________________ Jennifer L. Eichstedt, Major Professor, PhD Date ________________________________________________________________________ Samuel P. Oliner, Committee Member, PhD Date ________________________________________________________________________ Elizabeth Watson, Committee Member, PhD Date ________________________________________________________________________ Jennifer L. Eichstedt, Graduate Coordinator, PhD Date ________________________________________________________________________ Christopher Hopper, Interim Dean for Research and Graduate Studies, PhD Date ABSTRACT Choosing Silence: The United States, Turkey and The Armenian Genocide Maral N. Attallah My work is a comparative/ historical analysis of the Armenian Genocide, and how the denial and treatment of this genocide by Turkey and the United States has affected the social psychological wellbeing of succeeding generations of Armenians. I explore the literature that documents Turkey’s denial of the Armenian Genocide, and I also consider the United State’s political stance (or lack there of) on the denial. I use historical sources (i.e. books, videotapes, scholarly journals, etc.) to compare the Armenian Genocide with other genocides (i.e. Jewish Holocaust, Rwanda, etc.), and I look specifically at the reasons behind the state-sponsored killings, methods of murder, and who were the killers. The majority of my thesis covers the Armenian Genocide, detailing what happened, how it happened and why it is denied. I draw on genocide studies and literature of the Armenian genocide. -

The Armenian Genocide and the Making of Modern Humanitarian Media in the US, 1915-1925

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 "Lest They Perish": The Armenian Genocide and the Making of Modern Humanitarian Media in the U.S., 1915-1925 Jaffa Panken University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Panken, Jaffa, ""Lest They Perish": The Armenian Genocide and the Making of Modern Humanitarian Media in the U.S., 1915-1925" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1396. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1396 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1396 For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Lest They Perish": The Armenian Genocide and the Making of Modern Humanitarian Media in the U.S., 1915-1925 Abstract Between celebrity spokesmen and late night informercials, international humanitarian aid organizations use multiple media strategies to generate public interest in their programs. Though this humanitarian media has seemingly proliferated in the past thirty years, these publicity campaigns are no recent phenomenon but one that emerged from the World War I era. "Lest They Perish" is a case study of the modernization of international humanitarian media in the U.S. during and after the Armenian genocide from 1915 to 1925. This study concerns the Near East Relief, an international humanitarian organization that raised and contributed over $100,000,000 in aid to the Armenians during these years of violence. As war raged throughout Europe and Western Asia, American governmental propagandists kept the public invested in the action overseas. Private philanthropies were using similar techniques aimed at enveloping prospective donors in "whirlwind campaigns" to raise funds.