University of Birmingham Ego Involvement Increases Doping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Product Catalogue 2020 Contents

PRODUCT CATALOGUE 2020 CONTENTS 04 Our Story 44 EGO Power+ Multi-Tool 08 The EGO Power+ System 56 EGO Power+ Mowers 12 EGO Power+ Warranties 64 EGO Power+ Line Trimmers & Brush Cutter 14 EGO Power+ Batteries & Chargers 72 EGO Power+ Hedge Trimmers 25 EGO Power+ vs. Petrol 78 EGO Power+ Shrub / Grass Shears 30 EGO Power+ Professional-X Range 80 EGO Power+ Chainsaws 36 EGO Power+ Professional-X Line Trimmers / Brush Cutters 86 EGO Power+ Blowers 38 EGO Power+ Professional-X Rotocut 94 EGO Power+ Accessories 40 EGO Power+ Professional-X Hedge Trimmers 99 EGO Power+ Product Features 42 EGO Power+ Professional-X Blower 2 | CONTENTS CONTENTS | 3 Challenge 2025 is our commitment to changing the future of gardening for the better. People use their tools to improve the environment around them, so why use petrol – a power source that will ultimately destroy the atmosphere? We believe that the future for outdoor power equipment is battery powered, and we want you to join us in making battery the number one choice within five short years. The time has come to take up the challenge, and together, create a cleaner, quieter and safer future. EGO is part of a global manufacturing business Our commitment to a 2-megawatt photovoltaic power station. Known as established in 1993, employing over 7,000 a greener environment ‘The Blue Roof’ the power this generates, year-on-year, OUR people and producing over 10 million units each saves the equivalent of 755 tonnes of coal, as well as year, which are sold in over 30,000 outlets in EGO’s commitment to innovation is driven by a cutting Sulphur Dioxide emissions by 50 tonnes and STORY 65 countries worldwide. -

View the Manual

A Important Health Warning: Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people with no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. Symptoms can include light-headedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, momentary loss of awareness, and loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents, watch for or ask children about these symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely to experience these seizures. The risk may be reduced by being farther from the screen; using a smaller screen; playing in a well-lit room, and not playing when drowsy or fatigued. If you or any relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. © 2019 The Codemasters Software Company Limited (“Codemasters”). All rights reserved. “Codemasters”®, “EGO”®, the Codemasters logo and “Grid”® are registered trademarks owned by Codemasters. “RaceNet”™ is a trademark of Codemasters. All rights reserved. Uses Bink Video. Copyright © 1997-2019 by RAD Game Tools, Inc. Powered by Wwise © 2006 - 2019 Audiokinetic Inc. All rights reserved. Ogg Vorbis Libraries © 2019, Xiph.Org Foundation. Portions of this software are copyright ©2019 The FreeType Project (www.freetype.org). All rights reserved. All other copyrights or trademarks are the property of their respective owners and are being used under license. -

Architecture and Implementation of the System for Serious Games in Unity 3D

Architecture and implementation of the system for serious games in Unity 3D Master Thesis Aleksei Penzentcev Brno, May 2015 Declaration Hereby I declare, that this paper is my original authorial work, which I have worked out by my own. All sources, references and literature used or excerpted during elaboration of this work are properly cited and listed in complete reference to the due source. Aleksei Penzentcev Advisor: RNDr. Barbora Kozliková, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor RNDr. Barbora Kozliková, Ph.D. for the opportunity to participate in the project of Department of Computer Graphics and Design, for her consultation and comments during the work on the thesis. Also I would like to thank Mgr. Jiří Chmelík, Ph.D. for the technical support and leading the mother project for my thesis called Newron1 and to all people participated in this project for inspiring communication and contribution to it. 1 http://www.newron.cz iii Abstract This thesis describes a way of designing architecture for a serious game in Unity 3D environment and implementation of interaction with the game via Kinect device. The architecture is designed using event-based system which makes easier adding new components into the game including support of other devices. The thesis describes main approaches used for creation of such system. The mini-game “Tower of Hanoi” is implemented as an example of usage event-based system. iv Keywords Unity 3D, game architecture, events, C#, game, game engines, Kinect, Tower of Hanoi, gestures recognition, patterns, singleton, observer, SortedList. v Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 5 2 Overview ....................................................................................................... -

Designing Together Apart Computer Supported Collaborative Design in Architecture

Thomas Kvan M A (Cantab), M Arch (Calif) Designing Together Apart Computer Supported Collaborative Design in Architecture Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Open University Milton Keynes England Discipline Design and Innovation Submitted: December 1998 Revised: June 1999 DESIGNING TOGETHER APART i ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. VI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................VII PUBLISHED WORK................................................................................................................ VIII ACRONYMS................................................................................................................................. IX 1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................1 1.1 PROPOSITION OF THIS THESIS..............................................................................................6 1.2 STRUCTURE OF THE THESIS.................................................................................................9 2 DESIGNING TOGETHER APART ...................................................................................10 2.1 AN OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................12 2.1.1 Technology in practices...........................................................................................14 -

The Relations Between Perceived Parent, Coach, and Peer Created

THE RELATIONS BETWEEN PERCEIVED PARENT, COACH, AND PEER CREATED MOTIVATIONAL CLIMATES, GOAL ORIENTATIONS, AND MENTAL TOUGHNESS IN HIGH SCHOOL VARSITY ATHLETES Nicholas M. Beck Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Trent A. Petrie, Major Professor Scott Martin, Committee Member Edward Watkins, Committee Member Camilo Ruggero, Committee Member Vicki Campbell, Chair of the Department of Psychology Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Beck, Nicholas M. The Relations between Perceived Parent, Coach, and Peer Created Motivational Climates, Goal Orientations, and Mental Toughness in High School Varsity Athletes. Doctor of Philosophy (Counseling Psychology), August 2014, 91 pp., 3 tables, 2 figures, references, 130 titles. Determining the factors that contribute to mental toughness development in athletes has become a focus for researchers as coaches, athletes, and others extol its influence on performance success. In this study we examined a model of mental toughness development based on achievement goal theory, assessing the relations between motivational climates, goal orientations, and mental toughness. Five hundred ninety-nine varsity athletes, representing 13 different sports from six different high schools in a southwestern United States school district, participated in the study. Athletes completed self-report measures assessing parent, peer, and coach motivational climates, goal orientations, and their mental toughness. Initially, I examined the measurement model and found it fit the data well both in the exploratory (SRMR = .06; CFI = .94) and confirmatory (SRMR = .06; CFI = .95) samples. Second, the structural model was examined and found to fit the data well in both the exploratory (SRMR = .08; CFI = .93) and confirmatory samples (SRMR = .07, CFI = .95). -

Application of Investigative Psychology to Psychodynamic

APPLICATION OF INVESTIGATIVE PSYCHOLOGY TO PSYCHODYNAMIC AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT THEORIES: EXAMINING TRAITS AND TYPOLOGIES OF SERIAL KILLERS BY JORDYN SMITH A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Forensic Psychology California Baptist University School of Behavioral Sciences 2018 i ii SCHOOL OF BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES The thesis of Jordyn Smith, “Application of Investigative Psychology to Psychodynamic and Human Development Theories: Examining Traits and Typologies of Serial Killers,” approved by her Committee, has been accepted and approved by the Faculty of the School of Behavioral Sciences, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Forensic Psychology. Thesis Committee: _____________________________ Anne-Marie Larsen, Ph.D., Associate Professor _____________________________ Jenny E. Aguilar, PsyD., Director, Assistant Professor Committee Chairperson April 27, 2018 iii DEDICATION To my husband, son and dog. Your continuous encouragement and loving support throughout my educational endeavors transformed my dreams into a reality. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge Dr. Jenny Aguilar and Dr. Anne- Marie Larsen for believing in my study and having patience with my countless inquiries. I would also like to acknowledge my parents, mother-in-law and father-in-law, and sister for allowing me time to study and attend class without worrying about my son. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge California Baptist University for giving me this opportunity. v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Application of Investigative Psychology to Psychodynamic and Human Development Theories: Examining Traits and Typologies of Serial Killers by Jordyn Smith School of Behavioral Sciences Jenny E. Aguilar, PsyD. -

Reflection and Expression in an Ego-Shooter Environment

Reflection and expression in an ego-shooter environment Maia Engeli Technical Ontwerp & Informatica, Architecture, University of Plymouth, UK [email protected] This paper is about editing ego-shooter games to elaborate and express ideas by means of virtual spaces. Ego- shooter games were chosen because they are a popular media and offer different possibilities for their alteration. The interesting and most challenging aspect is the search for new kinds of designs for the dynamic virtual space of the game environments. Examples from art and workshops with architecture students illustrate these explorations. Computer Games, Virtual Reality, Virtual Architecture, Digital Messages. Introduction Ego-shooter games are a popular kind of multi-user virtual reality environment. Reasons for their popularity include the attractiveness of game itself, the fact that they are relatively cheep, mostly open- source, their vivid online community exchanging information on every aspect of the game, and the possibilities to creatively expand the game. Ego-shooter games combine entertainment and participation, popularity and creativity, and the potential for “spontaneous networks” (Jahrmann / Moswitzer 2003). For these reasons ego-shooter games can serve as an appropriate means to explore architectonic interests in virtual reality. The virtual imagery and the virtual body motion in ego-shooter games have a particular and narrow ranged typology. But there is a modern quality to the way space is read by the player from his or her first- person (=ego) perspective. The player’s perception of the dynamic scenery focuses on the moving parts, which have to be categorized immediately into threatening or non-threatening object, enemy, friend, or neutral being. -

Realtime Ray Tracing for Current and Future Games

Realtime Ray Tracing for Current and Future Games J¨org Schmittler, Daniel Pohl, Tim Dahmen, Christian Vogelgesang, and Philipp Slusallek schmittler,sidapohl,morfiel,chrvog,slusallek ¡ @graphics.cs.uni-sb.de Abstract: Recently, realtime ray tracing has been developed to the point where it is becoming a possible alternative to the current rasterization approach for interactive 3D graphics. With the availability of a first prototype graphics board purely based on ray tracing, we have all the ingredients for a new generation of 3D graphics technology that could have significant consequences for computer gaming. However, hardly any research has been looking at how games could benefit from ray tracing. In this paper we describe our experience with two games: The adaption of a well known ego-shooter to a ray tracing engine and the development of a new game espe- cially designed to exploit the features of ray tracing. We discuss how existing features of games can be implemented in a ray tracing context and what new effects and impro- vements are enabled by using ray tracing. Both projects show how ray tracing allows for highly realistic images while it greatly simplifies content creation. 1 Introduction Ray tracing is a well-known method to achieve high quality and physically-correct images, but only recently its performance was improved to the point that it can now also be used for interactive 3D graphics for highly complex and dynamic scenes including global illu- mination [Wa04, WDS04, WBS03, BWS03, GWS04]. While the above systems still rely on distributed computing to achieve realtime perfor- mance, a first prototype of a purely ray tracing based graphics chip [SWWS04] shows that efficient hardware implementations are indeed possible and provide many advantages over rasterization This encourages the research on possible effects of ray tracing technology for computer games. -

EGO-TOPO: Environment Affordances from Egocentric Video

In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2020. EGO-TOPO: Environment Affordances from Egocentric Video Tushar Nagarajan1 Yanghao Li2 Christoph Feichtenhofer2 Kristen Grauman1;2 1 UT Austin 2 Facebook AI Research [email protected], flyttonhao, feichtenhofer, [email protected] Abstract cut onion pour salt wash pan take knife put onion peel potato First-person video naturally brings the use of a physi- cal environment to the forefront, since it shows the camera wearer interacting fluidly in a space based on his inten- tions. However, current methods largely separate the ob- served actions from the persistent space itself. We intro- duce a model for environment affordances that is learned directly from egocentric video. The main idea is to gain a human-centric model of a physical space (such as a kitchen) T = 1 → 8 T = 42→ 80 that captures (1) the primary spatial zones of interaction and (2) the likely activities they support. Our approach Untrimmed decomposes a space into a topological map derived from Egocentric first-person activity, organizing an ego-video into a series Video of visits to the different zones. Further, we show how to Figure 1: Main idea. Given an egocentric video, we build a topo- link zones across multiple related environments (e.g., from logical map of the environment that reveals activity-centric zones videos of multiple kitchens) to obtain a consolidated repre- and the sequence in which they are visited. These maps capture sentation of environment functionality. On EPIC-Kitchens the close tie between a physical space and how it is used by peo- and EGTEA+, we demonstrate our approach for learn- ple, which we use to infer affordances of spaces (denoted here with ing scene affordances and anticipating future actions in color-coded dots) and anticipate future actions in long-form video. -

Grid-Enabling and Virtualizing Mission-Critical Financial Services’ Applications

TECHNICAL WHITEPAPER Grid-Enabling and Virtualizing Mission-Critical Financial Services’ Applications AUGUST 2006 WWW.PLATFORM.COM 2 Grid-Enabling and Virtualizing Mission-Critical Financial Services Applications Table of Contents Executive Summary............................................................................................3 1. Solution Overview.........................................................................................4 2. Platform Symphony Architecture......................................................................4 3. Grid-Enabling Compute-Intensive Applications with Platform Symphony................5 3.1 High Availability of Symphony-Enabled Applications..........................................................................7 3.2 Performance and Scalability of Symphony-Enabled Applications..........................................................7 3.3 Platform Symphony Grid-Enablement Patterns for Service-Oriented Applications.....................................8 3.4 Platform Symphony for Grid-Enablement APIs....................................................................................9 3.5 Platform Symphony and Application Technology Interoperability..........................................................9 4. Grid Resource Orchestration in Platform Symphony.........................................12 4.1 Ownership and Policy-based Sharing of Resources...........................................................................14 4.2 Guaranteed Service Level Agreement.............................................................................................14 -

LJMU Research Online

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LJMU Research Online LJMU Research Online Tang, SOT and Hanneghan, M State-of-the-Art Model Driven Game Development: A Survey of Technological Solutions for Game-Based Learning http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/205/ Article Citation (please note it is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from this work) Tang, SOT and Hanneghan, M (2011) State-of-the-Art Model Driven Game Development: A Survey of Technological Solutions for Game-Based Learning. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 22 (4). pp. 551-605. ISSN 1093-023x LJMU has developed LJMU Research Online for users to access the research output of the University more effectively. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LJMU Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of the record. Please see the repository URL above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information please contact [email protected] http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/ State of the Art Model Driven Game Development: A Survey of Technological Solutions for Game-Based Learning Stephen Tang* and Martin Hanneghan Liverpool John Moores University, James Parsons Building, Byrom Street, Liverpool, L3 3AF, United Kingdom * Corresponding author. -

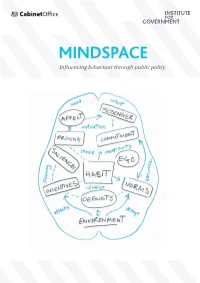

MINDSPACE: Influencing Behaviour Through Public

MINDSPACE Influencing behaviour through public policy 2 Discussion document – not a statement of government policy Contents Foreword 4 Executive Summary 7 Introduction: Understanding why we act as we do 11 MINDSPACE: A user‟s guide to what affects our behaviour 18 Examples of MINDSPACE in public policy 29 Safer communities 30 The good society 36 Healthy and prosperous lives 42 Applying MINDSPACE to policy-making 49 Public permission and personal responsibility 63 Conclusions and future challenges 73 Annexes 80-84 MINDSPACE diagram 80 New possible approaches to current policy problems 81 New frontiers of behaviour change: Insight from experts 83 References 85 Discussion document – not a statement of government policy 3 Foreword Influencing people‟s behaviour is nothing new to Government, which has often used tools such as legislation, regulation or taxation to achieve desired policy outcomes. But many of the biggest policy challenges we are now facing – such as the increase in people with chronic health conditions – will only be resolved if we are successful in persuading people to change their behaviour, their lifestyles or their existing habits. Fortunately, over the last decade, our understanding of influences on behaviour has increased significantly and this points the way to new approaches and new solutions. So whilst behavioural theory has already been deployed to good effect in some areas, it has much greater potential to help us. To realise that potential, we have to build our capacity and ensure that we have a sophisticated understanding of what does influence behaviour. This report is an important step in that direction because it shows how behavioural theory could help achieve better outcomes for citizens, either by complementing more established policy tools, or by suggesting more innovative interventions.