From Sorry to Superb: Everything You Need to Know About Great Bus Stops Acknowledgments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CASE STUDY Vehicle Platform from Pilot to Priority: Faster Bus Service in New York City

ConnectedCASE STUDY Vehicle Platform From pilot to priority: Faster bus service in New York City A pioneering collaboration between the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) and Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) has led to the implementation of an Opticom Transit Signal Priority (TSP) throughout some of New York City’s busiest roadways, helping to Solution Overview address the issue of slow bus journeys caused by major traffic congestion. PROBLEM The innovative approach leveraged existing Traditionally, TSP involves Bus travel times slow, and getting slower vehicle and citywide infrastructure, allowing • Route M15-SBS: 2nd highest purpose-built hardware on the the efficient rollout of TSP across nearly passenger loads in city 6,000 buses and 12,700 intersections1 vehicle and at the intersection. • Congested, intermodal route in New York City. It will also allow the MTA But for the New York, the sheer - Heavy pedestrian, bicycle traffic to easily deploy updates and upgrades as - Unloading trucks volume of intersections and technology improves, providing access vehicles that needed to be to new features and refinements without • Cross traffic coordination required • Urban canyon reduced GPS equipped would have taken requiring costly and time-consuming hardware maintenance. effectiveness years to install. The decision • 13,000 traffic signals -- difficult to to test and then implement a As a result, New York City bus riders should deploy hardware see improved travel times and more reliable centralized, software-based service as they use the country’s largest SOLUTION TSP solution was critical to a bus network. Deliver centralized transit signal priority successful deployment. control • Leverage existing infrastructure, Moving Millions of People in a Megacity investments New York City has the largest transit ridership in the United States. -

New York City Transit and Bus Committee Meeting 2 Broadway, 20Th Floor Conference Room New York, NY 10004 Monday, 6/24/2019 10:30 AM - 12:00 PM ET

Transit and Bus Committee Meeting June 2019 NYCT President Andy Byford joined Transit Veterans at the WWII Memorial located in the lobby of New York City Transit’s Downtown Brooklyn headquarters on June 6 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day. Three Transit employees made the ultimate sacrifice for their country in the ensuing Normandy campaign that began in June 1944. New York City Transit and Bus Committee Meeting 2 Broadway, 20th Floor Conference Room New York, NY 10004 Monday, 6/24/2019 10:30 AM - 12:00 PM ET 1. PUBLIC COMMENT PERIOD 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES – MAY 20, 2019 Meeting Minutes - Page 4 3. COMMITTEE WORK PLAN Work Plan - Page 15 4. PRESIDENT'S REPORT a. Customer Service Report i. President's Commentary President's Commentary - Page 23 ii. Subway Report Subway Report - Page 26 iii. NYCT, MTA Bus Report NYCT, MTA Bus Report - Page 57 iv. Paratransit Report Paratransit Report - Page 81 v. Accessibility Update Accessibility Update - Page 95 vi. Strategy & Customer Experience Strategy & Customer Experience - Page 97 b. Safety Report Safety Report - Page 103 c. Crime Report Crime Report - Page 107 d. NYCT, SIR, MTA Bus Financial & Ridership Reports NYCT, SIR, MTA Bus Financial and Ridership Reports - Page 118 e. Capital Program Status Report Capital Program Status Report - Page 169 5. SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS (No Materials) a. Fast Forward - One Year Update b. L Project Update- JMT Consulting 6. PROCUREMENTS Procurement Cover, Staff Summary, Resolution - Page 179 a. Non-Competitive NYCT Non-Competitive Actions - Page 184 b. Competitive NYCT Competitive Actions - Page 186 c. Ratifications NYCT Ratifications - Page 191 7. -

1 Policy Options Brief To: Councilman Ydanis A

Policy Options Brief To: Councilman Ydanis A. Rodriguez, Chairperson of the New York City Council Committee on Transportation; Daryl C. Irick, Acting President of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority From: Kyle Rectenwald and Paul Evans Subject: Detrimental Effects of Limited Transport Access on Low-Income New Yorkers Date: March 23, 2017 Problem: The New Yorkers Who Need Access to Transit the Most Have it the Least New York City’s low-income communities are being severely underserved by the city’s public transportation system. Around 58% of the city’s poorest residents, more than any other income group, rely on the subway and bus systems for transportation (Bendix). Yet for a variety of reasons to be outlined, these residents are being increasingly isolated from access to transit and presented with limited mobility options. Marginalization from the city’s transport network means limited access to the opportunities provided by a vibrant city like New York. This inequitable situation has real, detrimental effects on people’s lives. For one young man, simply getting from his home in West Harlem to attend college in the Bronx requires an hour or more walk every day (Stolper and Rankin 4). For many residents, lack of transport means they are unable to even pick children up from childcare, go grocery shopping, or access basic, fundamental services like hospitals and schools. For the city’s low-income population, limited access to transport is a key factor locking them into a spiral of poverty. As Councilmember David Greenfield recently said, “You can’t get out of poverty if you can’t get to your job” (Foley). -

October 5, 2016 Veronique Hakim President, New York City Transit

UNITED STATES HOUSE THE NEW YORK THE NEW YORK THE COUNCIL OF THE OF REPRESENTATIVES STATE SENATE STATE ASSEMBLY CITY OF NEW YORK October 5, 2016 Veronique Hakim President, New York City Transit Metropolitan Transportation Authority 2 Broadway New York, NY 1004 Dear President Hakim, Please restore the M15 Select Bus Service at 72nd Street. The M15 Limited stopped at 72nd Street until it was phased out in favor of M15 Select Bus Service. With high bus-dependent populations, infrequent local service, crosstown bus service, hospitals, community support and opening of the Second Avenue Subway with a station at 72nd Street, now is the perfect opportunity to increase ridership by restoring M15 Select Bus Service at 72nd Street. 72nd Street Only Location Omitted from Select Bus Service When Select Bus Service was introduced to First and Second Avenues on the M15 route, Select Bus Stations replaced Limited Service stops in every location above Houston Street other than East 72nd Street. Since October 2010, residents living in the East 72nd Street area, for example at 73rd off York Avenue, now must choose between walking three avenues and six blocks, more than half a mile, to a Select Bus Service bus station at 67th or 79th Streets and Second Avenue, versus half that distance to 72nd Street. Walking more than half a mile in both directions is simply too far for many residents. High Concentration of Seniors and Children Need Select Bus Service at 72nd Street The neighborhood that would be served by a Select Bus Service station at 72nd Street includes Census Tracts in Manhattan number 124, 126, 132, and 134 spanning from 69th to 79th between 3rd Avenue and the East River with a population of 44,756, one of the highest near any Select Bus station: 8,679 or 32.7% of households include children (under 18) or seniors (65 and over) who may rely on bus service due to age: o 3,326 or 12.5% of households have children under 18 years-old. -

Improving Bus Service in New York a Thesis Presented to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Improving Bus Service in New York A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Architecture and Planning COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment Of the requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Urban Planning By Charles Romanow May 2018 Abstract New York City’s transportation system is in a state of disarray. City street are clogged with taxi’s and for-hire vehicles, subway platforms are packed with straphangers waiting for delayed trains and buses barely travel faster than pedestrians. The bureaucracy of City and State government in the region causes piecemeal improvements which do not keep up with the state of disrepair. Bus service is particularly poor, moving at rates incomparable with the rest of the country. New York has recently made successful efforts at improving bus speeds, but only so much can be done amidst a city of gridlock. Bus systems around the world faced similar challenges and successfully implemented improvements. A toolbox of near-immediate and long- term options are at New York’s disposal dealing directly with bus service as well indirect causes of poor bus service. The failing subway system has prompted public discussion concerning bus service. A significant cause of poor service in New York is congestion. A number of measures are capable of improving congestion and consequently, bus service. Due to the city’s limited capacity at implementing short-term solutions, the most highly problematic routes should receive priority. Routes with slow speeds, high rates of bunching and high ridership are concentrated in Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn which also cater to the most subway riders. -

The Path to Partnership: How Cities and Transit Systems Can Stop

The Path to Partnership: How Cities and Transit Systems Can Stop Worrying and Join Forces Introduction In order to keep and attract riders, transit must be frequent, fast, and reliable. Maintaining frequent, fast, and reliable service in the congested conditions of most American cities requires prioritizing street level transit above automobile traffic, through measures like bus lanes, queue jumps, and signal priority. Relative to large capital projects, bus priority measures provide immediate improvements in travel time and reliability at a small fraction of the cost, and can be accomplished overnight with the right combination of paint, light duty street installations, and enforcement. The projects profiled in this study, including a bus lane in Everett, MA, New York City’s Select Bus Service, and Seattle’s Rapid Ride have seen travel time savings of 10-30%. While on-street transit improvements can be done quickly and cheaply, they aren’t necessarily easy to accomplish. Getting them done usually requires two things: · Political will and leadership from mayors, transit system managers and board members, and other leaders who must be willing to defend potentially controversial street and service changes like removing on-street parking spaces for a bus lane, or eliminating bus stops that are too close together. · Structuring transit agencies and city street agencies to more quickly and effectively deliver on-street transit projects. This may mean forging new relationships and decision-making processes, gathering new data, hiring for different skills, and figuring out new ways to prioritize projects. 2 Transit street projects can be tough to get done when there’s no history of doing them. -

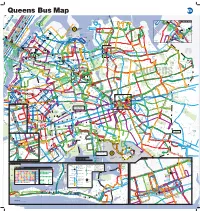

Queens Bus Map a Map of the Queens Bus Routes

Columbia University 125 St W 122 ST M 1 6 M E 125 ST Cathedral 4 1 Pkwy (110 St) 101 M B C M 5 6 3 116 St 102 125 St W 105 ST M M 116 St 60 4 2 3 Cathedral M SBS Pkwy (110 St) 2 B C M E 126 ST 103 St 1 MT MORRIS PK W 103 M 5 AV M E 124 2 3 102 10 E 120 ST M Central Park ST North (110 St) M MADISON AV 35 1 M M M B C 103 1 2 3 4 1 M 103 St 96 St 15 M 110 St 1 E 110 ST6 SBS QW 96 ST ueens Bus Map RANDALL'S BROADWAY 1 ISLAND B C 86 St NY Water 96 St Taxi Ferry W 88 ST Q44 SBS 44 6 to Bronx Zoo 103 St SBS M M MADISON AV Q50 15 35 50 WHITESTONE COLUMBUS AV E 106 ST F. KENNEDY COLLEGE POINT to Co-op City SBS 96 St 3 AV SHORE FRONT THROGS NECK BRIDGE B C BRIDGE CENTRAL PARK W 6 PARK 7 AV 2 AV BRIDGE POWELLS COVE BLVD 86 St 25 WHITESTONE CLI 147 ST N ROBERT ED KOCH LIC / Queens Plaza 96 St 5 AV AV 15A QUEENSBORO R 103 103 150 ST N 10 15 1 AV R W Q D COLLEGE POINT BLVD T 41 AV M 119 ST BRIDGE B C R 9 AV O 66 37 AV 15 FD NVILLE ST 81 St 96 ST QM QM QM QM M 7 AV 9 AV 69 38 AV 5 AV RIKERS POPPENHUSEN AV R D 102 1 2 3 4 21 St 35 NTE R 102 Queens- WARDS E 157 ST M 4 100 ISLAND 9 AV C 44 11 AV QM QM QM QM QM bridge 160 ST 166 ST 9 154 ST 162 ST 1 M M M ISLAND AV 15A 5 6 10 12 15 F M 5 6 SBS UTOPIA 39 AV 1 15 60 Q44 FORT QM QM QM QM QM 10 M 86 St COLLEGE BEECHHURST 13 Next stop QM 14 AV 15 PKWY TOTTEN 21 ST 102 M 111 ST 25 16 17 20 18 21 CRESCENT ST 2 86 St SBS POINT QM QM QM 14 AV 123 ST SERVICE RD NORTH QNS PLZ N 39 Av 2 14 AV Lafayette Av 2 QM QM QM QM QM QM M M Q 65 76 2 32 16 E 92 ST 21 AV 14 AV 20B 32 40 AV N W M 101 QM 2 24 31 32 34 35 3 LAGUARDIA 14 RD 15 AV E M E 91 ST 15 AV 32 SER 14 RD QM QM QM QM QM QM M 3 M ASTORIA WA 31 ST 101 21 ST 100 VICE RD S. -

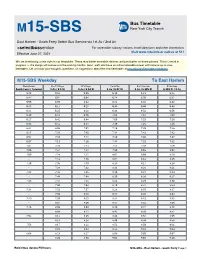

MTA M15-SBS Bus Timetable

Bus Timetable M15-SBS New York City Transit East Harlem - South Ferry Select Bus Service via 1st Av / 2nd Av +selectbusservice For accessible subway stations, travel directions and other information: Visit www.mta.info or call us at 511 Effective June 27, 2021 We are introducing a new style to our timetables. These read better on mobile devices and print better on home printers. This is a work in progress — the design will evolve over the coming months. Soon, we'll also have an online timetable viewer with more ways to view timetables. Let us know your thoughts, questions, or suggestions about the new timetables at new.mta.info/timetables-feedback. M15-SBS Weekday To East Harlem Downtown East Village E Village Yorkville East Harlem E Harlem South Ferry / Terminal 1 Av / E 1 St 1 Av / E 14 St 1 Av / E 97 St 1 Av / E 125 St E 126 St / 2 Av 5:38 5:52 5:55 6:15 6:21 6:22 5:47 6:01 6:04 6:24 6:30 6:32 5:55 6:09 6:12 6:32 6:38 6:40 6:03 6:17 6:20 6:40 6:46 6:48 6:11 6:25 6:28 6:48 6:54 6:56 6:19 6:33 6:36 7:01 7:07 7:08 6:27 6:41 6:44 7:09 7:15 7:16 6:35 6:51 6:54 7:19 7:25 7:26 6:42 6:58 7:01 7:29 7:35 7:36 6:47 7:03 7:06 7:34 7:41 7:42 6:52 7:08 7:11 7:39 7:46 7:47 6:57 7:13 7:16 7:44 7:51 7:52 7:01 7:20 7:23 7:51 7:58 7:59 7:05 7:24 7:27 7:55 8:02 8:03 7:09 7:28 7:31 8:02 8:09 8:10 - 7:32 7:36 8:07 8:14 8:15 7:16 7:35 7:39 8:10 8:17 8:18 - 7:38 7:42 8:13 8:20 8:21 7:22 7:41 7:45 8:16 8:23 8:24 - 7:44 7:48 8:19 8:26 8:27 7:28 7:47 7:51 8:22 8:29 8:30 - 7:50 7:54 8:25 8:32 8:34 7:34 7:53 7:57 8:28 8:35 8:37 - 7:56 8:00 8:31 8:38 8:40 7:40 7:59 8:03 8:34 8:41 8:43 - 8:02 8:06 8:37 8:44 8:46 7:46 8:05 8:09 8:40 8:47 8:49 - 8:08 8:12 8:43 8:50 8:52 7:52 8:11 8:15 8:46 8:53 8:55 - 8:14 8:18 8:49 8:56 8:58 7:58 8:17 8:21 8:52 8:59 9:01 - 8:20 8:24 8:55 9:02 9:04 8:04 8:23 8:27 8:58 9:05 9:07 - 8:26 8:30 9:01 9:08 9:10 Bold times denote PM hours. -

Student Metrocard ® Two Ways to Pay Before You Board 2

® Student MetroCard Two Ways to Pay Before You Board 2. Coin Fare Collector Other travel tips: Use this machine if you have a HalfFare Can I make any transfer I want? Can I get off GET SCHOOLED 1. MetroCard Fare Collector Student MetroCard and your first trip is on a Select Bus Service changes the way buses the bus and then back on again? Select Bus. operate and makes your ride faster and more Use this machine if you have a Student MetroCard OR you have a Subject to applicable terms and conditions. Name (print) reliable. In addition to customers paying before Transfers from a local bus to a limited bus and Only valid for student named above on days when student's school is in session. HalfFare Student MetroCard that Pay your fare with coins, exact Student Transportation they board, this service features dedicated bus from a limited bus to local buses are allowed in Valid Monday to Friday, you swiped on a previous bus change only. 5:30 a.m. until 8:30 p.m. S lanes, enforcement against traffic violators, The 01-23-4567 The the same direction. You can’t get back on the Grades K-6 before getting on the Select Bus. The machine doesn’t take dollar Subject to applicable terms and conditions. Name (print) cameras that catch illegally parked cars and Only valid for student named above on days when student's school is in session. same bus you started on, though. bills, halfdollars, or pennies. Student Transportation trucks, and traffic signal priority, all contributing to Valid Monday to Friday, There are also some other bus transfers that are 5:30 a.m. -

Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 New York, New York New Starts Project Development Information Prepared December 2016

Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 New York, New York New Starts Project Development Information Prepared December 2016 The New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) proposes to extend heavy rail subway service 1.5 miles along the East Side of Manhattan with the Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 project. The project is the second of four planned sections of the Second Avenue Subway, and will connect the northern end of Phase 1 (opening soon) at 96th Street to the Lexington Avenue Line at 125th Street. The project will include three new stations, power substations, signal and communications systems, and car cleaning facilities. The project’s current estimated capital cost is $6 billion. MTA expects to seek $2 billion from the New Starts Program. MTA believes that the project will improve transit access on the East Side of Manhattan, alleviate congestion, improve service reliability on the Lexington Avenue Line, attract new transit riders, and provide intermodal connections to Metro North Railroad, Select Bus Service to LaGuardia Airport, and several local bus routes. The Locally Preferred Alternative for all four phases of the alignment was selected in 2001 and was adopted into the region’s fiscally constrained long-range transportation plan in 2003. MTA completed the environmental review process with a Record of Decision in 2004. MTA expects to complete an environmental reevaluation in early 2018, have the project enter the Engineering phase of the CIG program in late 2018, receive a Full Funding Grant Agreement in 2020, and open for revenue service between 2027 and 2029. . -

Filling the Gaps: COMMUTE and the Fight for Transit Equity in New York

FILLING THE GAPS COMMUTE and the Fight for Transit Equity in New York City SETH FREED WESSLER March 2010 APPLIED RESEARCH CENTER Racial Justice Through Media, Research and Activism Applied Research Center www.arc.org/greenjobs FILLING THE GAPS COMMUTE and the Fight for Transit Equity in New York City March 2010 Author Seth Freed Wessler Executive Director | Rinku Sen Research Director | Dominique Apollon Research Assistants | Karina Hurtado-Ocampo Copy Editor | Kathryn Duggan Art and Design Director | Hatty Lee Copyright 2010 Applied Research Center www.arc.org 900 Alice St., Suite 400 Oakland, CA 94607 510.653.3415 INTRODUCTION STANDING AT THE HEAD of A TABLE IN THE offICE of YouTH MINISTRIES for PEACE AND JUSTICE (YMPJ) IN THE SouTH BroNX, commuNITY orGANIZER JULIEN TErrELL opened a meeting of a dozen of the organization’s middle and high school student members by asking how many people in the room ride the bus every day. All of the young people raised their hands. “So buses matter a lot to you all?” asked Terrell. They nodded their heads. “Well what would you say if the city started cutting buses?” The room was silent. New York City’s buses are under siege. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), the New York State entity charged with operating the public transit systems in the region, has plunged into a sinking budget deficit by the financial crisis. In early 2009, the MTA responded by proposing to cut bus and train lines across the city, raise fares and even end subsidies for student fares. While advocates triumphed in pushing back most of the cuts at the time, the crisis remained, and a year later, New Yorkers once again face the prospect of widespread cuts to transit service. -

Advocates Bus Service Improvements Testimony to NYS Senate Standing

Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Advocates Bus Service Improvements Testimony to NYS Senate Standing Committee On Corporations, Authorities & Commissions and Standing Committee On Transportation by Mark Henry, President and Business Agent, ATU Local 1056 and Chair, ATU NYS Legislative Conference Board February 19, 2019 Thank you for the opportunity to advocate for necessary improvements to public transit in the City of New York. I am Mark Henry, President and Business Agent for Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local No. 1056; and Chair, ATU NYS Legislative Conference Board. I represent ATU Local 1056 which represents drivers and mechanics who work for MTA New York City Transit's Queens Bus Division and ATU Locals across the State of New York on their legislative concerns. Transit in this city operated by MTA focuses primarily on economics, income level and not the population’s needs; it’s the Tale of Two Different New York’s. As a mass transit professionals, ATU Locals across this city and state offers unique and valuable insights. We serve the riding public. At almost every opportunity discussing public transit, the ATU Locals in this city emphasizes that smartly investing in public transit keys growth in the economy and job creation. Moreover at this hearing on the MTA and transit network effectiveness, ATU emphasizes that cost-effective improvements in bus service offers the smartest and most effective means to deliver public transit improvements, including to the many so-called transit deserts identified in the City of New York. Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Testimony to NYS Senate Standing Committee On Corporations, Authorities & Commissions, February 19, 2019, page two Public transit serves as the lifeline for many true New Yorkers – especially those people of lower incomes – to shop, see their doctor, attend worship services, visit family members, and do many of the things that enrich their lives.