Ship to Shore: Integrating New York Harbor Ferries with Upland Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NY Waterway & IKEA Launching New Weekend Ferry Service to IKEA Brooklyn On

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Rubenstein (Wiley Norvell 646-422-9614, [email protected]) NY WATERWAY TO LAUNCH NEW WEEKEND FERRY SERVICE TO IKEA IN BROOKLYN Beginning Saturday, July 3, NY Waterway is launching a free new ferry service to IKEA in Red Hook, Brooklyn for IKEA customers from Pier 79/Midtown Ferry Terminal, Brookfield Place/Battery Park City and Pier 11/Wall Street. New Jersey passengers can connect to the new service from cross-Hudson ferries by transferring at any Manhattan terminal. The service will run on weekends and extend all summer long. “We hope to make the trip to IKEA a little bit easier and a lot more pleasant with a free ferry ride from our Manhattan terminals. We’re excited to partner with IKEA to launch this new service for the summer,” said Armand Pohan, President, CEO and Chairman of NY Waterway. “We are excited to reintroduce our ferry service to our customers after a year off,” said Mike Baker, New York Market Manager for IKEA. “At IKEA we believe that sustainability, accessibility and affordability should be included in every aspect of our customers’ journey.” NY Waterway is a safe way to travel, offering open-air top decks and continuous sanitizing of all terminals, ferries and shuttles. Face coverings are required inside terminals and inside all ferry cabins and shuttles, and social distancing is encouraged. NEW Weekend IKEA Brooklyn Ferry Service starting Saturday, July 3 Ferries will depart from Pier 79/Midtown Ferry Terminal between 11:05am and 7pm, making stops for pick-ups at Brookfield Place/Battery Park City, and Pier 11/Wall Street to IKEA in Red Hook. -

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1958

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1958 Part 14. Pacific Slope Basins in Oregon and Lower Columbia River Basin Prepared under the direction of J. V. B. WELLS, Chief, Surface Water Branch GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1568 Prepared in cooperation with the States of Oregon and Washington and with other agencies UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. - Price $1 (paper cover) PREFACE This report was prepared by the Geological Survey in coopera tion with the States of Oregon and Washington and with other agen cies, by personnel of the Water Resources Division, L. B. Leopold, chief, under the general direction of J. V. B. Wells, chief, Surface Water Branch, and F. J. Flynn, chief, Basic Records Section. The data were collected and computed under supervision of dis trict engineers, Surface Water Branch, as follows: K. N. Phillips...............>....................................................................Portland, Oreg, F. M. Veatch .................................................................................Jacoma, Wash. Ill CALENDAR FOR WATER YEAR 1958 OCTOBER 1957 NOVEMBER 1957 DECEMBER 1957 5 M T W T F S S M T W T P S S M T W T P S 12345 1 2 1234567 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3456789 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 -

CASE STUDY Vehicle Platform from Pilot to Priority: Faster Bus Service in New York City

ConnectedCASE STUDY Vehicle Platform From pilot to priority: Faster bus service in New York City A pioneering collaboration between the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) and Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) has led to the implementation of an Opticom Transit Signal Priority (TSP) throughout some of New York City’s busiest roadways, helping to Solution Overview address the issue of slow bus journeys caused by major traffic congestion. PROBLEM The innovative approach leveraged existing Traditionally, TSP involves Bus travel times slow, and getting slower vehicle and citywide infrastructure, allowing • Route M15-SBS: 2nd highest purpose-built hardware on the the efficient rollout of TSP across nearly passenger loads in city 6,000 buses and 12,700 intersections1 vehicle and at the intersection. • Congested, intermodal route in New York City. It will also allow the MTA But for the New York, the sheer - Heavy pedestrian, bicycle traffic to easily deploy updates and upgrades as - Unloading trucks volume of intersections and technology improves, providing access vehicles that needed to be to new features and refinements without • Cross traffic coordination required • Urban canyon reduced GPS equipped would have taken requiring costly and time-consuming hardware maintenance. effectiveness years to install. The decision • 13,000 traffic signals -- difficult to to test and then implement a As a result, New York City bus riders should deploy hardware see improved travel times and more reliable centralized, software-based service as they use the country’s largest SOLUTION TSP solution was critical to a bus network. Deliver centralized transit signal priority successful deployment. control • Leverage existing infrastructure, Moving Millions of People in a Megacity investments New York City has the largest transit ridership in the United States. -

Cultural Guide for Seniors: Brooklyn PHOTOGRAPHY

ART / DESIGN ARCHITECTURE DANCE / SING THEATRE / LIVE MONUMENTS GALLERIES / ® PARKSCultural Guide for Seniors: Brooklyn PHOTOGRAPHY Acknowledgments NYC-ARTS in primetime is made possible in part by First Republic Bank and by the Rubin Museum of Art. Funding for NYC-ARTS is also made possible by Rosalind P. Walter, The Paul and Irma Milstein Foundation, The Philip & Janice Levin Foundation, Elise Jaffe and Jeffrey Brown, Jody and John Arnhold, and The Lemberg Foundation. This program is NYC-ARTS.org supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. On multiple platforms, Thirteen/WNET’s Additional funding provided by members of NYC-ARTS aims to increase awareness of THIRTEEN. New York City’s nonprofit cultural organizations, whose offerings greatly benefit We are grateful to Megan Flood for residents and visitors—from children to adults, contributing the design of the cover of this and teenagers to senior citizens. publication. NYC-ARTS promotes cultural groups’ We are grateful for the cooperation of the activities and events to tri-state, national and cultural organizations that supplied information international audiences through nonprint media, for this guide. using new technologies as they develop. Through websites, television, mobile applications and social media, NYC-ARTS This program is supported, in part, by nurtures New York City’s position as a public funds from the New York City thriving cultural capital of the world, one that Department of Cultural Affairs. has both world renowned institutions and those that are focused on local communities. WNET 825 Eighth Avenue New York, NY 10019 http://WNET.org (212) 560-2000 Cover Design: Megan Flood Copyright © 2012 WNET Table of Contents A.I.R./Artists in Residence Gallery............................................................................. -

MTA Construction & Development, the Group Within the Agency Responsible for All Capital Construction Work

NYS Senate East Side Access/East River Tunnels Oversight Hearing May 7, 2021 Opening / Acknowledgements Good morning. My name is Janno Lieber, and I am the President of MTA Construction & Development, the group within the agency responsible for all capital construction work. I want to thank Chair Comrie and Chair Kennedy for the invitation to speak with you all about some of our key MTA infrastructure projects, especially those where we overlap with Amtrak. Mass transit is the lifeblood of New York, and we need a strong system to power our recovery from this unprecedented crisis. Under the leadership of Governor Cuomo, New York has demonstrated national leadership by investing in transformational mega-projects like Moynihan Station, Second Avenue Subway, East Side Access, Third Track, and most recently, Metro-North Penn Station Access, which we want to begin building this year. But there is much more to be done, and more investment is needed. We have a once-in-a-generation infrastructure opportunity with the new administration in Washington – and we thank President Biden, Secretary Buttigieg and Senate Majority Leader, Chuck Schumer, for their support. It’s a new day to advance transit projects that will turbo-charge the post-COVID economy and address overdue challenges of social equity and climate change. East Side Access Today we are on the cusp of a transformational upgrade to our commuter railroads due to several key projects. Top of the list is East Side Access. I’m pleased to report that it is on target for completion by the end of 2022 as planned. -

Ny Waterway Commuter Ferry/Bus Network

From: NY Waterway 4800 Avenue at Port Imperial Weehawken, NJ 07086 Rubenstein Contact: Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NY WATERWAY COMMUTER FERRY/BUS NETWORK NY Waterway operates the largest privately-owned commuter ferry service in the U.S., carrying more than 32,000 passenger trips per day – 10 million trips per year – on 34 boats serving 23 routes between New Jersey and Manhattan, and between Rockland and Westchester counties, and between Orange and Dutchess counties. Thousands of NY Waterway ferry commuters save an hour or more per trip, the equivalent of a one-month vacation every year. Ferries provide comfortable seating in climate-controlled cabins, but many passengers elect to ride outdoors, experiencing the exhilaration of the trip and the breath-taking views. Passengers’ biggest complaint is that the ride is too short. A fleet of 70 NY Waterway buses provide a free, seamless commute between ferry terminals in New York and New Jersey and inland locations. “Our commuter ferries provide safe, convenient and efficient commuter services, reducing traffic and pollution in the Metropolitan area,” says NY Waterway President & Founder Arthur E. Imperatore, who started the business in 1986. Operating out of beautiful ferry terminals on both sides of the Hudson River, NY Waterway provides an unrivaled commuting experience. Commuter routes include: Port Imperial in Weehawken NJ, to West 39th Street in Manhattan, all day, seven days a week. Port Imperial to Brookfield Place / Battery Park City Ferry Terminal, morning/evening rush hours, weekdays; all day weekends. Port Imperial to Pier 11 at Wall Street, morning/evening rush hours, weekdays. -

From Planyc to Onenyc: New York's Evolving Sustainability Policy

From PlaNYC to OneNYC: New York's Evolving Sustainability Policy http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steven-cohen/from-planyc-to-onenyc-n... Edition: US THE BLOG 04/27/2015 08:48 am ET | Updated Jun 27, 2015 Steven Cohen Executive Director, Columbia University's Earth Institute GETTY IMAGES/PHOTOALTO One of the signature accomplishments of New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg's 12 years as mayor was the development and implementation of New York City's first sustainability plan: PlaNYC 2030. Mayor Bloomberg saw projections of New York's population growth and realized that environmental goals needed to 1 of 7 1/28/2016 12:26 PM From PlaNYC to OneNYC: New York's Evolving Sustainability Policy http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steven-cohen/from-planyc-to-onenyc-n... be integrated into the city's economic development goals. The plan's focus on measurable accomplishments and frequent performance reporting mirrored the highly successful anti-crime techniques pioneered by the NYPD's CompStat system. Key to the success of PlaNYC was its clear status as a mayoral priority. PlaNYC joined environment to the mayor's top priority of economic development. Last week, we may have seen a similar moment in policy development as Mayor de Blasio linked sustainability to his top goal of poverty reduction. The fact that he is attempting to integrate sustainability with his highest priority is a strong indication that sustainability goals will continue to advance in New York City. The different goals of our very distinct mayors reflect the different conditions they inherited when they assumed office. Mayor Bloomberg took office less than one hundred days after the horror of the World Trade Center's destruction. -

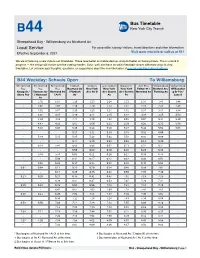

MTA B44 Bus Timetable

Bus Timetable B44 New York City Transit Sheepshead Bay - Williamsburg via Nostrand Av Local Service For accessible subway stations, travel directions and other information: Effective September 5, 2021 Visit www.mta.info or call us at 511 We are introducing a new style to our timetables. These read better on mobile devices and print better on home printers. This is a work in progress — the design will evolve over the coming months. Soon, we'll also have an online timetable viewer with more ways to view timetables. Let us know your thoughts, questions, or suggestions about the new timetables at new.mta.info/timetables-feedback. B44 Weekday: Schools Open To Williamsburg Sheepshead Sheepshead Sheepshead Flatbush Flatbush East Flatbush Crown Hts Bed-Stuy Williamsburg Williamsburg Bay Bay Bay Nostrand Av New York New York New York Fulton St / Bedford Av / Williamsbur Knapp St / Emmons Av Nostrand Av / Flatbush Av / Av D Av / Church Av / Eastern Nostrand Av Flushing Av g Br Plz / Shore Pky / Nostrand / Av U Av Av Py Lane 4 Av - 1:02 1:07 1:16 1:20 1:24 1:32 1:37 1:43 1:48 - 2:02 2:07 2:16 2:20 2:24 2:32 2:37 2:43 2:48 - 3:02 3:07 3:16 3:20 3:24 3:32 3:37 3:43 3:48 - 4:02 4:07 4:16 4:21 4:25 4:33 4:38 4:45 4:50 - 4:30 4:35 4:44 4:49 4:53 5:01 5:07 5:14 5:20 - 4:47 4:52 5:01 5:06 5:11 5:19 5:25 5:32 5:38 - 5:03 5:09 5:19 5:24 5:29 5:37 5:44 5:52 5:58 - - - 5:27 5:32 5:36 5:45 5:52 6:00 - - 5:19 5:25 5:35 5:40 5:44 5:53 6:00 6:09 - - - - 5:44 5:49 5:53 6:02 6:11 6:20 - - 5:34 5:41 5:53 5:58 6:02 6:13 6:22 6:31 - - - - 5:59 6:04 6:09 6:20 6:29 6:38 -

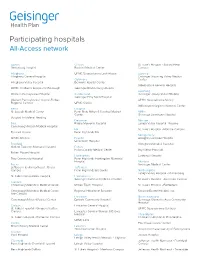

Participating Hospitals All-Access Network

Participating hospitals All-Access network Adams Clinton St. Luke’s Hospital - Sacred Heart Gettysburg Hospital Bucktail Medical Center Campus Allegheny UPMC Susquehanna Lock Haven Luzerne Allegheny General Hospital Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Columbia Center Allegheny Valley Hospital Berwick Hospital Center Wilkes-Barre General Hospital UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Geisinger Bloomsburg Hospital Lycoming Western Pennsylvania Hospital Cumberland Geisinger Jersey Shore Hospital Geisinger Holy Spirit Hospital Western Pennsylvania Hospital-Forbes UPMC Susquehanna Muncy Regional Campus UPMC Carlisle Williamsport Regional Medical Center Berks Dauphin St. Joseph Medical Center Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Mifflin Center Geisinger Lewistown Hospital Surgical Institute of Reading Delaware Monroe Blair Riddle Memorial Hospital Lehigh Valley Hospital - Pocono Conemaugh Nason Medical Hospital Elk St. Luke’s Hospital - Monroe Campus Tyrone Hospital Penn Highlands Elk Montgomery UPMC Altoona Fayette Abington Lansdale Hospital Uniontown Hospital Bradford Abington Memorial Hospital Guthrie Towanda Memorial Hospital Fulton Fulton County Medical Center Bryn Mawr Hospital Robert Packer Hospital Huntingdon Lankenau Hospital Troy Community Hospital Penn Highlands Huntingdon Memorial Hospital Montour Bucks Geisinger Medical Center Jefferson Health Northeast - Bucks Jefferson Campus Penn Highlands Brookville Northampton Lehigh Valley Hospital - Muhlenberg St. Luke's Quakertown Hospital Lackawanna Geisinger Community Medical Center St. Luke’s Hospital - Anderson Campus Cambria Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Moses Taylor Hospital St. Luke’s Hospital - Bethlehem Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center - Regional Hospital of Scranton Steward Easton Hospital, Inc. Lee Campus Lancaster Northumberland Conemaugh Miners Medical Center Ephrata Community Hospital Geisinger Shamokin Area Community Hospital Carbon Lancaster General Hospital St. Luke’s Hospital - Gnaden Huetten UPMC Susquehanna Sunbury Campus Lancaster General Women & Babies Hospital Philadelphia St. -

Anthony Bourdain Food Trail Pays Tribute to Bourdain’S Childhood Growing up in Leonia, New 2 Jersey, and Summers Spent at the Jersey Shore

ANTHONY BOURDAIN FOOD TRAIL 1 Discover the New Jersey culinary roots of the late Anthony Bourdain, celebrity chef, best- selling author and globe-trotting food and travel documentarian, on a newly designated food trail. The Anthony Bourdain Food Trail pays tribute to Bourdain’s childhood growing up in Leonia, New 2 Jersey, and summers spent at the Jersey Shore. The trail spotlights 10 New Jersey restaurants featured on CNN’s Emmy Award-winning Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown. 10 9 8 3 “To know Jersey is to love her.” 4 – Anthony Bourdain 7 5 6 Restaurant visitnj.org descriptions on next page NORTH JERSEY 1 Hiram’s Roadstand, Fort Lee “This is my happy place,” said Bourdain about this Fort Lee institution. Hiram’s has been slinging classic “ripper-style” (deep-fried) hot dogs since the 1930s. 1345 Palisade Ave., Fort Lee, NJ 07024 JERSEY SHORE For more information, go to visitnj.org, the official travel 2 Frank’s Deli & Restaurant, Asbury Park site for the State of New Jersey. The place to pick up overstuffed sandwiches on the way to the beach. “As I always like to say, good is good forever,” said Bourdain about Frank’s. Try the classic Jersey sandwich: sliced ham, provolone, tomato, onions, shredded • 130 Miles of Atlantic lettuce, roasted peppers, oil and vinegar. 1406 Main St., Asbury Park, NJ 07712 Coastline • Easy Access to New York 3 Kubel’s, Barnegat Light City and Philadelphia Bourdain grew up eating clams at the Jersey Shore, so this seaside restaurant, • Six Flags Great Adventure a Long Beach Island tradition since 1927, was a natural. -

New York City Transit and Bus Committee Meeting 2 Broadway, 20Th Floor Conference Room New York, NY 10004 Monday, 6/24/2019 10:30 AM - 12:00 PM ET

Transit and Bus Committee Meeting June 2019 NYCT President Andy Byford joined Transit Veterans at the WWII Memorial located in the lobby of New York City Transit’s Downtown Brooklyn headquarters on June 6 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day. Three Transit employees made the ultimate sacrifice for their country in the ensuing Normandy campaign that began in June 1944. New York City Transit and Bus Committee Meeting 2 Broadway, 20th Floor Conference Room New York, NY 10004 Monday, 6/24/2019 10:30 AM - 12:00 PM ET 1. PUBLIC COMMENT PERIOD 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES – MAY 20, 2019 Meeting Minutes - Page 4 3. COMMITTEE WORK PLAN Work Plan - Page 15 4. PRESIDENT'S REPORT a. Customer Service Report i. President's Commentary President's Commentary - Page 23 ii. Subway Report Subway Report - Page 26 iii. NYCT, MTA Bus Report NYCT, MTA Bus Report - Page 57 iv. Paratransit Report Paratransit Report - Page 81 v. Accessibility Update Accessibility Update - Page 95 vi. Strategy & Customer Experience Strategy & Customer Experience - Page 97 b. Safety Report Safety Report - Page 103 c. Crime Report Crime Report - Page 107 d. NYCT, SIR, MTA Bus Financial & Ridership Reports NYCT, SIR, MTA Bus Financial and Ridership Reports - Page 118 e. Capital Program Status Report Capital Program Status Report - Page 169 5. SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS (No Materials) a. Fast Forward - One Year Update b. L Project Update- JMT Consulting 6. PROCUREMENTS Procurement Cover, Staff Summary, Resolution - Page 179 a. Non-Competitive NYCT Non-Competitive Actions - Page 184 b. Competitive NYCT Competitive Actions - Page 186 c. Ratifications NYCT Ratifications - Page 191 7. -

MTA Metro-North Railroad Penn Station Access Project

Penn Station Access Project: Environmental Assessment and Section 4(f) Evaluation 1. Background and Purpose and Need 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) is proposing the Penn Station Access (PSA) Project, which would provide one-seat passenger rail service to Penn Station New York (PSNY) on Manhattan’s west side for Metro North Railroad’s (Metro-North) New Haven Line (NHL) customers (Proposed Project). MTA Construction and Development (MTACD)—the successor to MTA Capital Construction—would plan, design, and construct the Proposed Project and related public outreach, and Metro-North would operate and maintain the service. The Proposed Project would provide new rail service from New Haven, Connecticut (CT) to PSNY in Manhattan by following Amtrak’s Hell Gate Line (HGL) on the Northeast Corridor (NEC) through the eastern Bronx and western Queens. The Proposed Project would make infrastructure improvements on the HGL beginning in southeastern Westchester County—where NHL trains would divert onto the HGL at Shell Interlocking1—and extending to Harold Interlocking in Queens, joining MTA Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) Main line. As part of the Proposed Project, four new Metro-North stations would be constructed in the eastern Bronx at Hunts Point, Parkchester-Van Nest, Morris Park, and Co-op City. Figure 1-1 depicts the Proposed Project’s construction area and service area, and shows the relationship between the HGL, Metro-North, and LIRR systems. The proposed Metro-North service to PSNY would begin operations after the LIRR East Side Access (ESA) project service to Grand Central Terminal (GCT) is initiated. The Amended Full Funding Grant Agreement (August 2016) between MTA and Federal Transit Administration (FTA) projects ESA service to begin December 2023.