1 Policy Options Brief To: Councilman Ydanis A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CASE STUDY Vehicle Platform from Pilot to Priority: Faster Bus Service in New York City

ConnectedCASE STUDY Vehicle Platform From pilot to priority: Faster bus service in New York City A pioneering collaboration between the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) and Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) has led to the implementation of an Opticom Transit Signal Priority (TSP) throughout some of New York City’s busiest roadways, helping to Solution Overview address the issue of slow bus journeys caused by major traffic congestion. PROBLEM The innovative approach leveraged existing Traditionally, TSP involves Bus travel times slow, and getting slower vehicle and citywide infrastructure, allowing • Route M15-SBS: 2nd highest purpose-built hardware on the the efficient rollout of TSP across nearly passenger loads in city 6,000 buses and 12,700 intersections1 vehicle and at the intersection. • Congested, intermodal route in New York City. It will also allow the MTA But for the New York, the sheer - Heavy pedestrian, bicycle traffic to easily deploy updates and upgrades as - Unloading trucks volume of intersections and technology improves, providing access vehicles that needed to be to new features and refinements without • Cross traffic coordination required • Urban canyon reduced GPS equipped would have taken requiring costly and time-consuming hardware maintenance. effectiveness years to install. The decision • 13,000 traffic signals -- difficult to to test and then implement a As a result, New York City bus riders should deploy hardware see improved travel times and more reliable centralized, software-based service as they use the country’s largest SOLUTION TSP solution was critical to a bus network. Deliver centralized transit signal priority successful deployment. control • Leverage existing infrastructure, Moving Millions of People in a Megacity investments New York City has the largest transit ridership in the United States. -

From Planyc to Onenyc: New York's Evolving Sustainability Policy

From PlaNYC to OneNYC: New York's Evolving Sustainability Policy http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steven-cohen/from-planyc-to-onenyc-n... Edition: US THE BLOG 04/27/2015 08:48 am ET | Updated Jun 27, 2015 Steven Cohen Executive Director, Columbia University's Earth Institute GETTY IMAGES/PHOTOALTO One of the signature accomplishments of New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg's 12 years as mayor was the development and implementation of New York City's first sustainability plan: PlaNYC 2030. Mayor Bloomberg saw projections of New York's population growth and realized that environmental goals needed to 1 of 7 1/28/2016 12:26 PM From PlaNYC to OneNYC: New York's Evolving Sustainability Policy http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steven-cohen/from-planyc-to-onenyc-n... be integrated into the city's economic development goals. The plan's focus on measurable accomplishments and frequent performance reporting mirrored the highly successful anti-crime techniques pioneered by the NYPD's CompStat system. Key to the success of PlaNYC was its clear status as a mayoral priority. PlaNYC joined environment to the mayor's top priority of economic development. Last week, we may have seen a similar moment in policy development as Mayor de Blasio linked sustainability to his top goal of poverty reduction. The fact that he is attempting to integrate sustainability with his highest priority is a strong indication that sustainability goals will continue to advance in New York City. The different goals of our very distinct mayors reflect the different conditions they inherited when they assumed office. Mayor Bloomberg took office less than one hundred days after the horror of the World Trade Center's destruction. -

New York City Transit and Bus Committee Meeting 2 Broadway, 20Th Floor Conference Room New York, NY 10004 Monday, 6/24/2019 10:30 AM - 12:00 PM ET

Transit and Bus Committee Meeting June 2019 NYCT President Andy Byford joined Transit Veterans at the WWII Memorial located in the lobby of New York City Transit’s Downtown Brooklyn headquarters on June 6 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day. Three Transit employees made the ultimate sacrifice for their country in the ensuing Normandy campaign that began in June 1944. New York City Transit and Bus Committee Meeting 2 Broadway, 20th Floor Conference Room New York, NY 10004 Monday, 6/24/2019 10:30 AM - 12:00 PM ET 1. PUBLIC COMMENT PERIOD 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES – MAY 20, 2019 Meeting Minutes - Page 4 3. COMMITTEE WORK PLAN Work Plan - Page 15 4. PRESIDENT'S REPORT a. Customer Service Report i. President's Commentary President's Commentary - Page 23 ii. Subway Report Subway Report - Page 26 iii. NYCT, MTA Bus Report NYCT, MTA Bus Report - Page 57 iv. Paratransit Report Paratransit Report - Page 81 v. Accessibility Update Accessibility Update - Page 95 vi. Strategy & Customer Experience Strategy & Customer Experience - Page 97 b. Safety Report Safety Report - Page 103 c. Crime Report Crime Report - Page 107 d. NYCT, SIR, MTA Bus Financial & Ridership Reports NYCT, SIR, MTA Bus Financial and Ridership Reports - Page 118 e. Capital Program Status Report Capital Program Status Report - Page 169 5. SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS (No Materials) a. Fast Forward - One Year Update b. L Project Update- JMT Consulting 6. PROCUREMENTS Procurement Cover, Staff Summary, Resolution - Page 179 a. Non-Competitive NYCT Non-Competitive Actions - Page 184 b. Competitive NYCT Competitive Actions - Page 186 c. Ratifications NYCT Ratifications - Page 191 7. -

New York City Rules! Regulatory Models for Environmental and Public Health

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2015 New York City Rules! Regulatory Models for Environmental and Public Health Jason J. Czarnezki Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Environmental Law Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Jason J. Czarnezki, New York City Rules! Regulatory Models for Environmental and Public Health, 66 Hastings L.J. 1621 (2015), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/999/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles New York City Rules! Regulatory Models for Environmental and Public Health JASON J. CZARNEZKI* Scholars have become increasingly interested in facilitating improvement in environmental and public health at the local level. Over the lastfew years, former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the New York City Council have proposed and adopted numerous environmental and public health initiatives, providing a useful case study for analyzing the development and success (or failure) of various regulatory tools, and offering larger lessons about regulation that can be extrapolated to other substantive areas. This Article, first, seeks to categorize and evaluate these "New York Rules," creating a new taxonomy to understanddifferent types of regulation. These "New York Rules" include bans, informational regulation, education, infrastructure,mandates, standard-setting, and economic (dis)incentives. -

October 5, 2016 Veronique Hakim President, New York City Transit

UNITED STATES HOUSE THE NEW YORK THE NEW YORK THE COUNCIL OF THE OF REPRESENTATIVES STATE SENATE STATE ASSEMBLY CITY OF NEW YORK October 5, 2016 Veronique Hakim President, New York City Transit Metropolitan Transportation Authority 2 Broadway New York, NY 1004 Dear President Hakim, Please restore the M15 Select Bus Service at 72nd Street. The M15 Limited stopped at 72nd Street until it was phased out in favor of M15 Select Bus Service. With high bus-dependent populations, infrequent local service, crosstown bus service, hospitals, community support and opening of the Second Avenue Subway with a station at 72nd Street, now is the perfect opportunity to increase ridership by restoring M15 Select Bus Service at 72nd Street. 72nd Street Only Location Omitted from Select Bus Service When Select Bus Service was introduced to First and Second Avenues on the M15 route, Select Bus Stations replaced Limited Service stops in every location above Houston Street other than East 72nd Street. Since October 2010, residents living in the East 72nd Street area, for example at 73rd off York Avenue, now must choose between walking three avenues and six blocks, more than half a mile, to a Select Bus Service bus station at 67th or 79th Streets and Second Avenue, versus half that distance to 72nd Street. Walking more than half a mile in both directions is simply too far for many residents. High Concentration of Seniors and Children Need Select Bus Service at 72nd Street The neighborhood that would be served by a Select Bus Service station at 72nd Street includes Census Tracts in Manhattan number 124, 126, 132, and 134 spanning from 69th to 79th between 3rd Avenue and the East River with a population of 44,756, one of the highest near any Select Bus station: 8,679 or 32.7% of households include children (under 18) or seniors (65 and over) who may rely on bus service due to age: o 3,326 or 12.5% of households have children under 18 years-old. -

Improving Bus Service in New York a Thesis Presented to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Improving Bus Service in New York A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Architecture and Planning COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment Of the requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Urban Planning By Charles Romanow May 2018 Abstract New York City’s transportation system is in a state of disarray. City street are clogged with taxi’s and for-hire vehicles, subway platforms are packed with straphangers waiting for delayed trains and buses barely travel faster than pedestrians. The bureaucracy of City and State government in the region causes piecemeal improvements which do not keep up with the state of disrepair. Bus service is particularly poor, moving at rates incomparable with the rest of the country. New York has recently made successful efforts at improving bus speeds, but only so much can be done amidst a city of gridlock. Bus systems around the world faced similar challenges and successfully implemented improvements. A toolbox of near-immediate and long- term options are at New York’s disposal dealing directly with bus service as well indirect causes of poor bus service. The failing subway system has prompted public discussion concerning bus service. A significant cause of poor service in New York is congestion. A number of measures are capable of improving congestion and consequently, bus service. Due to the city’s limited capacity at implementing short-term solutions, the most highly problematic routes should receive priority. Routes with slow speeds, high rates of bunching and high ridership are concentrated in Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn which also cater to the most subway riders. -

CYCLING in NEW YORK CITY NACTO Designing Cities September 2016 Sean Quinn, Senior Director, NYCDOT Office of Bicycle and Pedestrian Programs

CYCLING IN NEW YORK CITY NACTO Designing Cities September 2016 Sean Quinn, Senior Director, NYCDOT Office of Bicycle and Pedestrian Programs 1 OVERVIEW • Snapshot of ridership in NYC • How did we get here? • Policy • Network Development and Planning • Support Elements • What’s Next? nyc.gov/dot 2 Snapshot of ridership in NYC 1 nyc.gov/dot 3 NYC IS GROWING As the city grows, there is higher demand on the transportation system and people are increasingly turning to mass transit, FHV carpooling, and cycling. nyc.gov/dot 4 Percent of Adult New Yorkers who Ride a Bike (NYC DOHMH) CYCLING IN NEW YORK CITY 25% of adult New Yorkers, nearly 1.6 million people, ride a bike (at least once in the past year) 2014 Of those adult New Yorkers, about three-quarters of a million (778,000) ride a bike regularly (at least several times a month) nyc.gov/dot CYCLING IN NEW YORK CITY Number of Adult New Yorkers Who Rode a Bike at Least Once in the Past Year +49% Growth in the number of New Yorkers who ride a bike several times a month (2009-2014) +340k Increase in the number of New Yorkers who bike at least once a year (2009-2014) nyc.gov/dot CYCLING IN NEW YORK CITY Estimates of Daily Cycling Activity by Year +350% Growth in daily cycling between 1990 and 2015 +80% Growth In daily cycling between 2010 and 2015 nyc.gov/dot 7 Between 2010 and 2015, cycling to CYCLING IN PEER CITIES work has grown twice as fast as other major cities Percent Growth: 2010-2015 Commute to Work - Rolling Three Year Average comparing NYC to Other Cities +80% New York +39% Peer Cities Peer cities include Portland, OR; Chicago, IL; San Francisco, CA; Seattle, WA; Washington, D.C.; Minneapolis, MN; Boston, MA. -

CYCLING in the CITY Cycling Trends In

CYCLING IN THE CITY Cycling Trends in NYC May 2016 Introduction Methods A Snapshot Number of Cyclists Commuters and Trips per Day Cycling in the City Trends over Time Citywide Total and Frequent Cyclists Table of Contents Daily Cycling Commuters by Borough Peer Cities East River Bridges Growth by Bridge Midtown Citi Bike Appendix Data Types, Sources, and Limitations Estimate of Daily Cycling With the expansion of the bicycle network on City streets, miles of new greenway paths in public parks, and the introduction of bike share, there have never been more people biking in New York City. In recent years, the City has experienced a sea change in the way that people ride bikes. Creation of community bike networks beyond the core encourages people to use a bicycle to get around their neighborhoods. Construction of new stretches of path along greenways such as the Brooklyn Waterfront and the Bronx River makes it more enticing for cyclists to take recreational rides. Miles of protected on-street bike lanes are emboldening Introduction Cycling in the City the more cautious and risk-averse New Yorkers to take to the streets on a bike, while Citi Bike makes cycling a more Over the past two decades, New York City has seen tremendous growth in convenient option for quick trips around the City and multi- cycling, reflecting broad efforts to expand the city’s bicycle infrastructure. In modal commutes—even for those who do not own a bicycle. the mid-1990s, NYC DOT established a bicycle program to oversee development of the city’s fledgling bike network. -

The Path to Partnership: How Cities and Transit Systems Can Stop

The Path to Partnership: How Cities and Transit Systems Can Stop Worrying and Join Forces Introduction In order to keep and attract riders, transit must be frequent, fast, and reliable. Maintaining frequent, fast, and reliable service in the congested conditions of most American cities requires prioritizing street level transit above automobile traffic, through measures like bus lanes, queue jumps, and signal priority. Relative to large capital projects, bus priority measures provide immediate improvements in travel time and reliability at a small fraction of the cost, and can be accomplished overnight with the right combination of paint, light duty street installations, and enforcement. The projects profiled in this study, including a bus lane in Everett, MA, New York City’s Select Bus Service, and Seattle’s Rapid Ride have seen travel time savings of 10-30%. While on-street transit improvements can be done quickly and cheaply, they aren’t necessarily easy to accomplish. Getting them done usually requires two things: · Political will and leadership from mayors, transit system managers and board members, and other leaders who must be willing to defend potentially controversial street and service changes like removing on-street parking spaces for a bus lane, or eliminating bus stops that are too close together. · Structuring transit agencies and city street agencies to more quickly and effectively deliver on-street transit projects. This may mean forging new relationships and decision-making processes, gathering new data, hiring for different skills, and figuring out new ways to prioritize projects. 2 Transit street projects can be tough to get done when there’s no history of doing them. -

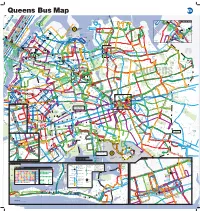

Queens Bus Map a Map of the Queens Bus Routes

Columbia University 125 St W 122 ST M 1 6 M E 125 ST Cathedral 4 1 Pkwy (110 St) 101 M B C M 5 6 3 116 St 102 125 St W 105 ST M M 116 St 60 4 2 3 Cathedral M SBS Pkwy (110 St) 2 B C M E 126 ST 103 St 1 MT MORRIS PK W 103 M 5 AV M E 124 2 3 102 10 E 120 ST M Central Park ST North (110 St) M MADISON AV 35 1 M M M B C 103 1 2 3 4 1 M 103 St 96 St 15 M 110 St 1 E 110 ST6 SBS QW 96 ST ueens Bus Map RANDALL'S BROADWAY 1 ISLAND B C 86 St NY Water 96 St Taxi Ferry W 88 ST Q44 SBS 44 6 to Bronx Zoo 103 St SBS M M MADISON AV Q50 15 35 50 WHITESTONE COLUMBUS AV E 106 ST F. KENNEDY COLLEGE POINT to Co-op City SBS 96 St 3 AV SHORE FRONT THROGS NECK BRIDGE B C BRIDGE CENTRAL PARK W 6 PARK 7 AV 2 AV BRIDGE POWELLS COVE BLVD 86 St 25 WHITESTONE CLI 147 ST N ROBERT ED KOCH LIC / Queens Plaza 96 St 5 AV AV 15A QUEENSBORO R 103 103 150 ST N 10 15 1 AV R W Q D COLLEGE POINT BLVD T 41 AV M 119 ST BRIDGE B C R 9 AV O 66 37 AV 15 FD NVILLE ST 81 St 96 ST QM QM QM QM M 7 AV 9 AV 69 38 AV 5 AV RIKERS POPPENHUSEN AV R D 102 1 2 3 4 21 St 35 NTE R 102 Queens- WARDS E 157 ST M 4 100 ISLAND 9 AV C 44 11 AV QM QM QM QM QM bridge 160 ST 166 ST 9 154 ST 162 ST 1 M M M ISLAND AV 15A 5 6 10 12 15 F M 5 6 SBS UTOPIA 39 AV 1 15 60 Q44 FORT QM QM QM QM QM 10 M 86 St COLLEGE BEECHHURST 13 Next stop QM 14 AV 15 PKWY TOTTEN 21 ST 102 M 111 ST 25 16 17 20 18 21 CRESCENT ST 2 86 St SBS POINT QM QM QM 14 AV 123 ST SERVICE RD NORTH QNS PLZ N 39 Av 2 14 AV Lafayette Av 2 QM QM QM QM QM QM M M Q 65 76 2 32 16 E 92 ST 21 AV 14 AV 20B 32 40 AV N W M 101 QM 2 24 31 32 34 35 3 LAGUARDIA 14 RD 15 AV E M E 91 ST 15 AV 32 SER 14 RD QM QM QM QM QM QM M 3 M ASTORIA WA 31 ST 101 21 ST 100 VICE RD S. -

MTA M15-SBS Bus Timetable

Bus Timetable M15-SBS New York City Transit East Harlem - South Ferry Select Bus Service via 1st Av / 2nd Av +selectbusservice For accessible subway stations, travel directions and other information: Visit www.mta.info or call us at 511 Effective June 27, 2021 We are introducing a new style to our timetables. These read better on mobile devices and print better on home printers. This is a work in progress — the design will evolve over the coming months. Soon, we'll also have an online timetable viewer with more ways to view timetables. Let us know your thoughts, questions, or suggestions about the new timetables at new.mta.info/timetables-feedback. M15-SBS Weekday To East Harlem Downtown East Village E Village Yorkville East Harlem E Harlem South Ferry / Terminal 1 Av / E 1 St 1 Av / E 14 St 1 Av / E 97 St 1 Av / E 125 St E 126 St / 2 Av 5:38 5:52 5:55 6:15 6:21 6:22 5:47 6:01 6:04 6:24 6:30 6:32 5:55 6:09 6:12 6:32 6:38 6:40 6:03 6:17 6:20 6:40 6:46 6:48 6:11 6:25 6:28 6:48 6:54 6:56 6:19 6:33 6:36 7:01 7:07 7:08 6:27 6:41 6:44 7:09 7:15 7:16 6:35 6:51 6:54 7:19 7:25 7:26 6:42 6:58 7:01 7:29 7:35 7:36 6:47 7:03 7:06 7:34 7:41 7:42 6:52 7:08 7:11 7:39 7:46 7:47 6:57 7:13 7:16 7:44 7:51 7:52 7:01 7:20 7:23 7:51 7:58 7:59 7:05 7:24 7:27 7:55 8:02 8:03 7:09 7:28 7:31 8:02 8:09 8:10 - 7:32 7:36 8:07 8:14 8:15 7:16 7:35 7:39 8:10 8:17 8:18 - 7:38 7:42 8:13 8:20 8:21 7:22 7:41 7:45 8:16 8:23 8:24 - 7:44 7:48 8:19 8:26 8:27 7:28 7:47 7:51 8:22 8:29 8:30 - 7:50 7:54 8:25 8:32 8:34 7:34 7:53 7:57 8:28 8:35 8:37 - 7:56 8:00 8:31 8:38 8:40 7:40 7:59 8:03 8:34 8:41 8:43 - 8:02 8:06 8:37 8:44 8:46 7:46 8:05 8:09 8:40 8:47 8:49 - 8:08 8:12 8:43 8:50 8:52 7:52 8:11 8:15 8:46 8:53 8:55 - 8:14 8:18 8:49 8:56 8:58 7:58 8:17 8:21 8:52 8:59 9:01 - 8:20 8:24 8:55 9:02 9:04 8:04 8:23 8:27 8:58 9:05 9:07 - 8:26 8:30 9:01 9:08 9:10 Bold times denote PM hours. -

Planyc PROGRESS REPORT 2009 Introduction Or’S Office on Earth Day 2007, We Put Forward Planyc, a Long- Term Vision for a Sustainable New York City

PROGRESS REPORT 2009 A GREENER, GREATER NEW YORK The City of New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg This page left intentionally blank PROGRESS REPORT 2009 OUR GOALS PAGE Create homes for almost a million more New Yorkers, while making housing 6 Housing more affordable and sustainable Ensure that all New Yorkers live Open Space within a 10-minute walk of a park 10 Clean up all contaminated land Brownfi elds in New York City 13 Open 90% of our waterways for recreation by reducing water pollution 16 Water Quality and preserving our natural areas Develop critical backup systems for our aging water network to 20 Water Network ensure long-term reliability Improve travel times by adding transit capacity for millions more residents, visitors, and workers 23 Transportation Reach a full “state of good repair” on New York City’s roads, subways, and rails for the fi rst time in history Provide cleaner, more reliable power for every New Yorker by upgrading our 29 Energy energy infrastructure Achieve the cleanest air quality Air Quality of any big city in America 34 Reduce our global warming Climate Change emissions by 30% 38 PROGRESS REPORT 2009 PlaNYC 1 “Each of the individual initiatives I’ve just described will not only strengthen our economic foundation and improve our quality of life; collectively, The City of New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg they will also form a frontal assault on the biggest challenge of all: global climate change.” Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg Earth Day, 2007 2 PlaNYC PROGRESS REPORT 2009 Introduction or’s Office On Earth Day 2007, we put forward PlaNYC, a long- term vision for a sustainable New York City.