Bird Conservation Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

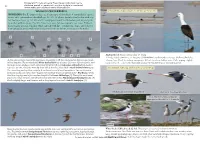

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

Biogeographical Profiles of Shorebird Migration in Midcontinental North America

U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Technical Report Series Information and Biological Science Reports ISSN 1081-292X Technology Reports ISSN 1081-2911 Papers published in this series record the significant find These reports are intended for the publication of book ings resulting from USGS/BRD-sponsored and cospon length-monographs; synthesis documents; compilations sored research programs. They may include extensive data of conference and workshop papers; important planning or theoretical analyses. These papers are the in-house coun and reference materials such as strategic plans, standard terpart to peer-reviewed journal articles, but with less strin operating procedures, protocols, handbooks, and manu gent restrictions on length, tables, or raw data, for example. als; and data compilations such as tables and bibliogra We encourage authors to publish their fmdings in the most phies. Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review appropriate journal possible. However, the Biological Sci and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. ence Reports represent an outlet in which BRD authors may publish papers that are difficult to publish elsewhere due to the formatting and length restrictions of journals. At the same time, papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. To purchase this report, contact the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161 (call toll free 1-800-553-684 7), or the Defense Technical Infonnation Center, 8725 Kingman Rd., Suite 0944, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060-6218. Biogeographical files o Shorebird Migration · Midcontinental Biological Science USGS/BRD/BSR--2000-0003 December 1 By Susan K. -

Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members. -

Calidris Himantopus (Stilt Sandpiper)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Calidris himantopus (Stilt sandpiper) Family: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Order: Charadriiformes (Shorebirds and Waders) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig 1. Stilt sandpiper, Calidris himantopus http://www.arkive.org/stilt-sandpiper/calidris-himantopus/image-G86449.html TRAITS. Stilt sandpipers on average are 20.3 – 23 cm in length, weigh 55g and have a life expectancy of about 11 years. In general, the males are more slender than females and have a long neck with a thin, black decurved bill that droops at the tip and long, dull green legs (Hilty, 2002). Female stilt sandpipers are slightly larger than their male counterparts and possess a brown ventral barring (Fig. 1) (Jehl Jr 1973). The non-breeding plumage of these birds consists of the upper body part being mostly plain grey with a white patch on its rump while the lower part of the body is white. In addition, the fore neck and sides of the chest are smudged grey (Hilty, 2002). The breeding plumage differs from the non-breeding plumage. The upper body turns a greyish brown while the lower body turns a dirty white. Additionally, the crown and UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour cheeks are reddish brown, there is the presence of a narrow white eyebrow stripe and the under parts of the body are black in colour (Hilty, 2002). Juveniles have an upper body that is scaled buff with the fore neck and sides of the chest containing fine grey streaks (Hilty, 2002). ECOLOGY. -

British Birds |

VOL. LU JULY No. 7 1959 BRITISH BIRDS WADER MIGRATION IN NORTH AMERICA AND ITS RELATION TO TRANSATLANTIC CROSSINGS By I. C. T. NISBET IT IS NOW generally accepted that the American waders which occur each autumn in western Europe have crossed the Atlantic unaided, in many (if not most) cases without stopping on the way. Yet we are far from being able to answer all the questions which are posed by these remarkable long-distance flights. Why, for example, do some species cross the Atlantic much more frequently than others? Why are a few birds recorded each year, and not many more, or many less? What factors determine the dates on which they cross? Why are most of the occurrences in the autumn? Why, despite the great advantage given to them by the prevail ing winds, are American waders only a little more numerous in Europe than European waders in North America? To dismiss the birds as "accidental vagrants", or to relate their occurrence to weather patterns, as have been attempted in the past, may answer some of these questions, but render the others still more acute. One fruitful approach to these problems is to compare the frequency of the various species in Europe with their abundance, migratory behaviour and ecology in North America. If the likelihood of occurrence in Europe should prove to be correlated with some particular type of migration pattern in North America this would offer an important clue as to the causes of trans atlantic vagrancy. In this paper some aspects of wader migration in North America will be discussed from this viewpoint. -

Migratory Shorebird Guild

Migratory Shorebird Guild Piping Plover Charadrius melodus Sanderling Calidris alba Semipalmated Plover Charadrius semipalmatus Red Knot Calidris canutus Black-bellied Plover Pluvialis squatarola Marbled Godwit Limosa fedoa American Golden Plover Pluvialis dominica Buff-breasted Sandpiper Tryngites subruficollis Wimbrel Numenius phaeopus White-rumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus Pectoral Sandpiper Calidris melanotos Greater Yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca Purple Sandpiper Calidris maritima Lesser Yellowlegs Tringa flavipes Stilt Sandpiper Calidris himantopus Solitary Sandpiper Tringa solitaria Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago gallinago delicata Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularia American Avocet Recurvirostra Americana Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda Least Sandpiper Calidris minutilla Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla Short-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus griseus Western Sandpiper Calidris mauri Long-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus scolopaceus Dunlin Calidris alpina Contributors: Felicia Sanders and Thomas M. Murphy DESCRIPTION Photograph by SC DNR Taxonomy and Basic Description The migratory shorebird guild is composed of birds in the Charadrii suborder. Migrants in South Carolina represent three families: Scolopacidae (sandpipers), Charadriidae (plovers) and Recurvirostridae (avocets). Sandpipers are the most diverse family of shorebirds. Their tactile foraging strategy encompasses probing in soft mud or sand for invertebrates. Plovers are medium size birds, with relatively short, thick bills and employ a distinctive foraging strategy. They stand, looking for prey and then run to feed on detected invertebrates. Avocets are large shorebirds with long recurved bills and partial webbing between the toes. They feed employing both tactile and visual methods. Shorebirds are characterized by long legs for wading and wings designed for quick flight and transcontinental migrations. Migrations can span continents; for example, red knots migrate from the Canadian arctic to the southern tip of South America. -

Seven Deadly Stints and Their Friends an Introduction to Calidris Sandpipers – Part 1 Jon L

Seven Deadly Stints and their Friends An Introduction to Calidris Sandpipers – Part 1 Jon L. Dunn Larry Sansone photos 13 October 2020 Los Angeles Birders Genus Calidris – Composed of 23 species the largest genus within the large family (94 species worldwide, 66 in North America) of Scolopacidae (Sandpipers). – All 23 species in the genus Calidris have been found in North America, 19 of which have occurred in California. – Only Great Knot, Broad-billed Sandpiper, Temminck’s Stint, and Spoon-billed Sandpiper have not been recorded in the state, and as for Great Knot, well half of one turned up! Genus Calidris – The genus was described by Marrem in 1804 (type by tautonymy, Red Knot, 1758 Linnaeus). – Until 1934, the genus was composed only of the Red Knot and Great Knot. – This genus is composed of small to moderate sized sandpipers and use a variety of foraging styles from probing in water to picking at the shore’s edge, or even away from water on mud or the vegetated border of the mud. – As within so many families or large genre behavior offers important clues to species identification. Genus Calidris – Most, but not all, species migrate south in their alternate (breeding) or juvenal plumage, molting largely once they reach their more southerly wintering grounds. – Most species nest in the arctic, some farther north than others. Some species breed primarily in Eurasia, some in North America. Some are Holarctic. – The majority of species are monotypic (no additional recognized subspecies). Genus Calidris – In learning these species one -

Shorebird Identification 5 SHOREBIRD IDENTIFICATION Usually Over 20 Mm Except in Least, Semipalmated and Buff Breasted

4 EBBA News February 1973 Shorebird Identification 5 SHOREBIRD IDENTIFICATION usually over 20 mm except in Least, Semipalmated and Buff breasted. Neck medium to long. 4 toes (except 3 in Sanderling) • BY CHANDLER S, ROBBINS* Back speckrea-or streaked in small species (indistinct markings on Spotted Sandpiper, and on Sanderling in winter). The superfamily of shorebirds is a heterogeneous group. Family Recurvirost ridae : Avocets, Stilts (7 species, 2 in Althou?h most members of this group are zeadily recognized as North Amer ica). Bi ll long, very slender; fegs very long and shoreb1rds, there are few distinctive characters that are pos slender, tarsus over 80 mm. 3 toes (stilt or 4 (avocet). sessed ~y all ~pecies. For example, nearly all shorebirds have long po1nted.w1ngs, but the woodcocks and lapwing have decided Family Phal aropodidae: Phalaropes (3 species, 3 in North ly rounded w1ngs. Most shorebirds have slender, soft bills, America). 4 toes , the front ones lobed, semipalmate. Female but the oystercatchers have heavy bills that are greatly com brighter colored than male. pres~ed l~ter~lly. The phalarope family has lobed toes, each spec1es w1th 1ts own particular type of lobe. The turnstones and most plovers have 3 toes, and most sandpipers have 4 toes Identifying Shorebirds to Species but one genus in each family does not conform to the general ' rule. The purpose of this paper is to assist banders in identi fying, to species, shorebirds that are in the hand. These pages The oystercatchers, avocets and stilts are so distinctive are not a substitute for a field guide or for manuals such as in all plumages that they will not be discussed in detail; Roberts, Forbush, Ridgway, or Coues. -

What Has Bonaparte Got to Do with Waders?

What has Bonaparte got to do with waders? Wader Quest Article number 15: 30/01/2021 Rick Simpson White-rumped Sandpipers © Elis Simpson SUPPORTING SHOREBIRD CONSERVATION Registered Charity (England and Wales) 1183748 © Wader Quest 2021. All rights reserved. 2 Well, not a lot if you are talking about Emperor Napoleon 1 Bonaparte of Waterloo fame. I suspect though, given the era in which he lived he may have eaten the odd one or two individuals, or their eggs, but beyond that there is, as far as I know, no other connection between him and waders. Or is there? It may be tenuous, but there is in fact a link, and that is because Napoleon was the uncle of one Charles Lucien Jules Laurent Bonaparte, 2nd Prince of Canino and Musignano (24 May 1803 – 29 July 1857) who, after being born in Paris was raised in Italy. Charles married his cousin Zénaïde and together they left for Philadelphia in the United States to live with Zénaïde's father, Joseph Bonaparte. On the journey across the Atlantic Charles collected a storm- petrel, which he later wrote up and gave the name Procellaria Wilsonii [sic] in a paper in 1824, although Wilson’s Petrel is now attributed to Heinrich Kuhl in 1820 and now called Oceanites oceanicus. In 1838 he coined the genus Zenaida, after his wife, for the Mourning Dove Zenaida macroura and Charles Lucien Jules Laurent Bonaparte. its relatives, and is responsible for giving scientific Lithograph by T. H. Maguire, 1849 — wikipedia names to many birds including a number of wader species. -

54971 GPNC Shorebirds

A P ocket Guide to Great Plains Shorebirds Third Edition I I I By Suzanne Fellows & Bob Gress Funded by Westar Energy Green Team, The Nature Conservancy, and the Chickadee Checkoff Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 • Identification Tips • 4 Plovers I Black-bellied Plover • 6 I American Golden-Plover • 8 I Snowy Plover • 10 I Semipalmated Plover • 12 I Piping Plover • 14 ©Bob Gress I Killdeer • 16 I Mountain Plover • 18 Stilts & Avocets I Black-necked Stilt • 19 I American Avocet • 20 Hudsonian Godwit Sandpipers I Spotted Sandpiper • 22 ©Bob Gress I Solitary Sandpiper • 24 I Greater Yellowlegs • 26 I Willet • 28 I Lesser Yellowlegs • 30 I Upland Sandpiper • 32 Black-necked Stilt I Whimbrel • 33 Cover Photo: I Long-billed Curlew • 34 Wilson‘s Phalarope I Hudsonian Godwit • 36 ©Bob Gress I Marbled Godwit • 38 I Ruddy Turnstone • 40 I Red Knot • 42 I Sanderling • 44 I Semipalmated Sandpiper • 46 I Western Sandpiper • 47 I Least Sandpiper • 48 I White-rumped Sandpiper • 49 I Baird’s Sandpiper • 50 ©Bob Gress I Pectoral Sandpiper • 51 I Dunlin • 52 I Stilt Sandpiper • 54 I Buff-breasted Sandpiper • 56 I Short-billed Dowitcher • 57 Western Sandpiper I Long-billed Dowitcher • 58 I Wilson’s Snipe • 60 I American Woodcock • 61 I Wilson’s Phalarope • 62 I Red-necked Phalarope • 64 I Red Phalarope • 65 • Rare Great Plains Shorebirds • 66 • Acknowledgements • 67 • Pocket Guides • 68 Supercilium Median crown Stripe eye Ring Nape Lores upper Mandible Postocular Stripe ear coverts Hind Neck Lower Mandible ©Dan Kilby 1 Introduction Shorebirds, such as plovers and sandpipers, are a captivating group of birds primarily adapted to live in open areas such as shorelines, wetlands and grasslands.