The Dwelling House of James Shearer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Registration Form

CROSS-PARTY GROUP REGISTRATION FORM NAME OF CROSS-PARTY GROUP Cross-Party Group on Towns and Town Centres PURPOSE OF THE GROUP AND PROPOSED DISCUSSION TOPICS 1. Please state the purpose of the Group. 2. Please also provide a brief explanation of the purpose of the Group and why the purpose is in the public interest. 3. Please also provide details of any overlaps with the purpose of existing Cross- Party Groups and an explanation of why, regardless of any such overlap, the Group should be established. 4. Please also provide an indication of the topics which the Group anticipates discussing in the forthcoming 12 months. The purpose of the Group is to analyse policy prescriptions and develop ideas and innovations. This will help Scotland’s towns and town centres through the current economic climate to emerge stronger, smarter, cleaner, healthier and greener. The Group will discuss ways in which Scotland’s towns can work towards sustainable economic growth through greater vibrancy and vitality. The Group intends to discuss leadership, enterprise, inclusion and digital in relation to the towns agenda. MSP MEMBERS OF THE GROUP Please provide names and party designation of all MSP members of the Group. George Adam (SNP) Jackie Bailie (Scottish Labour) Neil Bibby (Scottish Labour) Graeme Dey (SNP) Jenny Gilruth (SNP) Daniel Johnson (Scottish Labour) Alex Johnstone (Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party) Alison Johnstone (Scottish Green Party) Gordon Lindhurst (Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party) Angus MacDonald (SNP) Gillian Martin (SNP) Willie Rennie (Scottish Liberal Democrats) John Scott (Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party) Andy Wightman (Scottish Green Party) NON-MSP MEMBERS OF THE GROUP For organisational members please provide only the name of the organisation, it is not necessary to provide the name(s) of individuals who may represent the organisation at meetings of the Group. -

Spice Briefing

MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY AND REGION Scottish SESSION 1 Parliament This Fact Sheet provides a list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during the first parliamentary session, Fact sheet 12 May 1999-31 March 2003, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represented. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSPs: Historical MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a Series number of constituencies. 30 March 2007 This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order with the MSP’s name, the party the MSP was elected to represent and the corresponding region. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs elected to represent each region. Abbreviations used: Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats SNP Scottish National Party SSP Scottish Socialist Party 1 MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY: SESSION 1 Constituency MSP Region Aberdeen Central Lewis Macdonald (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen North Elaine Thomson (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen South Nicol Stephen (LD) North East Scotland Airdrie and Shotts Karen Whitefield (Lab) Central Scotland Angus Andrew Welsh (SNP) North East Scotland Argyll and Bute George Lyon (LD) Highlands & Islands Ayr John Scott (Con)1 South of Scotland Ayr Ian -

Fact Sheet Msps Mps and Meps: Session 4 11 May 2012 Msps: Current Series

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament I nfor mation C entre l ogo Scottish Parliament Fact sheet MSPs MPs and MEPs: Session 4 11 May 2012 MSPs: Current Series This Fact Sheet provides a list of current Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs), Members of Parliament (MPs) and Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represent. Abbreviations used: Scottish Parliament and European Parliament Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Ind Independent Lab Scottish Labour Party LD Scottish Liberal Democrats NPA No Party Affiliation SNP Scottish National Party UK Parliament Con Conservative and Unionist Party Co-op Co-operative Party Lab Labour Party LD Liberal Democrats NPA No Party Affiliation SNP Scottish National Party Scottish Parliament and Westminster constituencies do not cover the same areas, although the names of the constituencies may be the same or similar. At the May 2005 general election, the number of Westminster constituencies was reduced from 72 to 59, which led to changes in constituency boundaries. Details of these changes can be found on the Boundary Commission’s website at www.statistics.gov.uk/geography/westminster Scottish Parliament Constituencies Constituency MSP Party Aberdeen Central Kevin Stewart SNP Aberdeen Donside Brian Adam SNP Aberdeen South and North Maureen Watt SNP Kincardine Aberdeenshire East Alex Salmond SNP Aberdeenshire West Dennis Robertson SNP Airdrie and Shotts Alex Neil SNP Almond Valley Angela -

Minutes of Meeting 9 September 2020 (268KB Pdf)

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE CROSS PARTY GROUP ON TOWNS AND TOWN CENTRES Wednesday, 9 September 2020, 13:00 – 14:15 Online Meeting 1. Welcome and Opening Remarks Convener, John Scott MSP welcomed all to the meeting. Attendees and Apologies are noted in Appendix 2. 2. Approval of the Minutes of the Meeting of the Cross Party Group held 13th March 2019. The Minutes of the Meeting were accepted as a true and accurate record. 3. AGM Business John Scott MSP introduces AGM business. The Minutes of the last AGM Meeting held 4th September 2019 were accepted as a true and accurate record. Gillian Martin MSP proposes J Scott continues as Convener. Seconded by Neil Bibby MSP. Accepted by J Scott MSP. J Scott MSP proposes G Martin to continue as Deputy Convener. Seconded by N Bibby MSP. Accepted by G Martin MSP. J Scott MSP proposes N Bibby MSP to continue as Deputy Convener. Seconded by G Martin MSP. Accepted by N Bibby MSP. Agreement reached that Scotland’s Towns Partnership to continue as secretary to the group. J Scott summarised the group’s activities in the year to date and forward plans. This and other required reporting will be available in the annual report on the parliament website following the meeting. 4. ‘Scotland’s Towns Post-Covid – The Recovery’ Phil Prentice, Chief Officer, Scotland’s Towns Partnership and National Director, Scotland’s Improvement Districts gave an overview on the focus on recovery and on the good behaviours coming out of the pandemic. The Scottish Government quickly entered the dialogue and supported the Covid-19 BIDs Resilience Fund to help provide local solutions. -

Legislative Consent Memorandum- Ivory Bill Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body

Published 21 September 2018 SP Paper 379 7th Report, 2018 (Session 5) Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee Comataidh Atharrachadh Clìomaid is Ath-leasachaidh Fearann Legislative Consent Memorandum- Ivory Bill Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee Legislative Consent Memorandum- Ivory Bill, 7th Report, 2018 (Session 5) Contents Membership ____________________________________________________________1 Background ____________________________________________________________2 Consultation on the Bill __________________________________________________3 Financial Implications for Scotland _________________________________________3 Provisions that Relate to Scotland __________________________________________3 The Scottish Government's Position on Legislative Consent _____________________4 Scrutiny of the Legislative Consent Memorandum _____________________________4 Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee Legislative Consent Memorandum- Ivory Bill, 7th Report, 2018 (Session 5) Environment, Climate Change -

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Glasgow February 1978 ProQuest Number: 13804140 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13804140 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Contents Acknowledgments iii Abbreviations iv Notes on dating and currency vii Abstract viii Introduction to the society of Glasgow: its environment, constitution and institutions. 1 Prelude: the formation of parties in Glasgow, 1645-8 30 PART ONE The struggle for Kirk and King, 1648-52 Chapter 1 The radical ascendancy in Glasgow from October 1648 to the fall of the Western Association in December 1650. 52 Chapter II The time of trial: the revival of malignancy in Glasgow, and the last years of the radical Councils, December 1650 - March 1652. 70 PART TWO Glasgow under the Cromwellian Union, 1652-60 Chapter III A malignant re-assessment: the conservative rule in Glasgow, 1652-5. -

Good Morning All, Further to My Previous

From: Coote S (Simon) On Behalf Of Enterprise and Skills Chair Sent: 03 November 2017 10:09 To: Enterprise and Skills Chair; [Redacted] Subject: RE: Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board - Change of plan regarding the first meeting Good morning all, Further to my previous email, I can now confirm that CEOs will not be required for this meeting. Please accept our apologies for any inconvenience around travel plans, diaries, etc. Best regards, Simon, on behalf of Nora Senior, Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board Chair _____________________________________________ From: Coote S (Simon) On Behalf Of Enterprise and Skills Chair Sent: 02 November 2017 14:25 To: [Redacted] Cc: Enterprise and Skills PMO; Dolan G (Gillian); Gallacher K (Karen); McQueen C (Craig) Subject: FW: Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board - Change of plan regarding the first meeting Good afternoon all, Please see the email below from Nora Senior to Board members relating to the first meeting of the Strategic Board. You will see her intention is keep the date for a meeting with the four agencies. We’ll be in touch soon to with an indication of the revised agenda and arrangements. Thanks, Simon Coote, on behalf of Nora Senior, Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board Chair _____________________________________________ From: Coote S (Simon) On Behalf Of Enterprise and Skills Chair Sent: 02 November 2017 12:48 To: Enterprise and Skills Chair Subject: Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board - Change of plan regarding the first meeting Dear Board Member, As you are aware from the formal letter of invitation I sent inviting you to become a member of the new Enterprise and Skills Strategic Board, we were aiming to hold the first meeting on 7th November. -

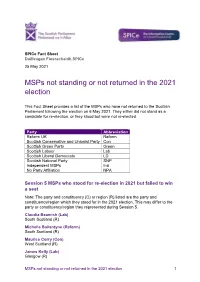

Msps Not Standing Or Not Returned in the 2021 Election

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 25 May 2021 MSPs not standing or not returned in the 2021 election This Fact Sheet provides a list of the MSPs who have not returned to the Scottish Parliament following the election on 6 May 2021. They either did not stand as a candidate for re-election, or they stood but were not re-elected. Party Abbreviation Reform UK Reform Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Con Scottish Green Party Green Scottish Labour Lab Scottish Liberal Democrats LD Scottish National Party SNP Independent MSPs Ind No Party Affiliation NPA Session 5 MSPs who stood for re-election in 2021 but failed to win a seat Note: The party and constituency (C) or region (R) listed are the party and constituency/region which they stood for in the 2021 election. This may differ to the party or constituency/region they represented during Session 5. Claudia Beamish (Lab) South Scotland (R) Michelle Ballantyne (Reform) South Scotland (R) Maurice Corry (Con) West Scotland (R) James Kelly (Lab) Glasgow (R) MSPs not standing or not returned in the 2021 election 1 Gordon Lindhurst (Con) Lothian (R) Joan McAlpine (SNP) South Scotland (R) John Scott (Con) Ayr (C) Paul Wheelhouse (SNP) South Scotland (R) Andy Wightman (Ind) Highlands and Islands (R) MSPs who were serving at the end of Parliamentary Session 5 but chose not to stand for re-election in 2021 Bill Bowman (Con) North East Scotland (R) Aileen Campbell (SNP) Clydesdale (C) Peter Chapman (Con) North East Scotland (R) Bruce Crawford (SNP) Stirling (C) Roseanna Cunningham (SNP) -

Code of Conduct Rule Changes- Treatment of Others Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body

Published 17 February 2021 SP 940 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee Comataidh Inbhean, Dòighean-obrach is Cur-an-dreuchd Poblach Code of Conduct Rule changes- Treatment of Others Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee Code of Conduct Rule changes- Treatment of Others, 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Contents Introduction ____________________________________________________________1 Background ____________________________________________________________2 SPPA Committee Consideration ___________________________________________3 Consultation____________________________________________________________4 Recommendation _______________________________________________________5 Annex A: Code of Conduct Rule changes ___________________________________6 Annexe B: Written submissions ___________________________________________7 Annexe C: Extract from minutes ___________________________________________8 Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee Code of Conduct Rule changes- Treatment -

Rural Development Committee

RURAL DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE Tuesday 13 March 2001 (Afternoon) £5.00 Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body 2001. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ Fax 01603 723000, which is administering the copyright on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. Produced and published in Scotland on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body by The Stationery Office Ltd. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office is independent of and separate from the company now trading as The Stationery Office Ltd, which is responsible for printing and publishing Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body publications. CONTENTS Tuesday 13 March 2001 Col. FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE .................................................................................................................. 1739 RURAL DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE 7th Meeting 2001, Session 1 CONVENER *Alex Johnstone (North-East Scotland) (Con) DEPU TY CONVENER *Fergus Ewing (Inverness East, Nairn and Lochaber) (SNP) COMMI TTEE MEMBERS *Mrs Margaret Ewing (Moray) (SNP) *Alex Fergusson (South of Scotland) (Con) *Rhoda Grant (Highlands and Islands) (Lab) *Cathy Jamieson (Carric k, Cumnoc k and Doon Valley) (Lab) *Richard Lochhead (North-East Scotland) (SNP) *Mrs Mary Mulligan (Linlithgow ) (Lab) *Dr Elaine Murray (Dumfries) (Lab) *Mr Mike Rumbles (West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) (LD) *Mr Jamie Stone (Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross) (LD) *attended -

Scottish Parliament Election Preview: from Four Party Politics to Further Consolidation in the South of Scotland?

Scottish Parliament election preview: From four party politics to further consolidation in the South of Scotland? democraticaudit.com /2016/04/23/21269/ By Democratic Audit UK 2016-4-23 The Scottish Parliament elections are upon us, with the SNP expected to consolidate their current dominance over Labour and the Conservatives. Here, Alistair Clark looks at the contest in the South Scotland region, an area which has had a recent history of four party politics but may be seeing its political profile shift. Glen Trool in Dumfriesshire (Credit: Sean Kippin) Anyone looking at a map of the 2003 Scottish parliament election results in South Scotland would be struck by the fact that all four main parties were relevant contenders in the region. Labour, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats all held seats in the region, two each for the smaller parties, and five for Labour. The SNP were also strong challengers, second place in three marginals behind the Conservatives (Galloway & Upper Nithsdale), Labour (Kilmarnock and Loudon) and the Liberal Democrats in a three way marginal with Labour also involved (Tweedale, Ettrick and Lauderdale). By 2007, Labour still held five constituencies, but the Conservatives had added a third to their total, won from the Liberal Democrats. Following the redrawing of boundaries prior to the 2011 elections, the Liberal Democrats had dropped out of the picture, affected by the national swing against the party because of its participation in the UK coalition government. Instead, the SNP advance was echoed here, the party winning four seats, against three for the Conservatives and two for Labour. -

People and Parliament in Scotland, 1689-1702

PEOPLE AND PARLIAMENT IN SCOTLAND, 1689-1702 Derek John Patrick A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2002 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11061 This item is protected by original copyright People and Parliament in Scotland 1689 - 1702 Submitted by Derek John Patrick for the Degree of Ph.D. in the University of St. Andrews August 2002 Suppose I take a spurt, and mix Amang the wilds 0' Politics - Electors and elected - Where dogs at Court (sad sons 0' bitches!) Septennially a madness touches, Till all the land's infected ?o o Poems and Songs of Robert Bums, J. Barke (ed.), (London, 1960),321. Election Ballad at Close of Contest for Representing the Dumfries Burghs, 1790, Addressed to Robert Graham ofFintry. CONTENTS DECLARATION 11 ABBREVIATIONS 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VI ABSTRACT V11 INTRODUCTION 1 1 The European Context 1689 - 1702 9 2 The Scottish Nobility 1689 - 1702 60 3 Revolution in the Royal Burghs 1689 - 1697 86 4 The Shire Estate 1689 - 1697 156 5 The Origins of Opposition 1698 - 1700 195 6 The Evolution of Party Politics in Scotland 1700 - 1702 242 7 Legislation 1689 - 1702 295 8 Committee Procedure 1689 - 1702 336 CONCLUSION 379 APPENDICES 1 Noble Representation 1689 - 1702 385 2 Officers of State 1689 - 1702 396 3 Shire Representation 1689 - 1702 398 4 Burgh Representation 1689 - 1702 408 5 Court and Country 1700 - 1702 416 BIBLIOGRAPHY 435 DECLARATION (i) 1, Derek John Patrick, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approxi mately 110,000 words in length, has been written by me.