Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls

Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls Jack E. Hauck Treasures of Wenham History, Helen Frick Pg. 441 Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls In Wenham, for forty-five years Helen Clay Frick devoted her time, her resources and her ideas for public good, focusing on improving the quality of life of young, working-class girls. Her style of philanthropy went beyond donating money: she participated in helping thousands of these girls. It all began in the spring of 1909, when twenty-year-old Helen Frick wrote letters to the South End Settlement House in Boston, and to the YMCAs and churches in Lowell, Lawrence and Lynn, requesting “ten promising needy Protestant girls to be selected for a free two-week stay ”in the countryside. s In June, she welcomed the first twenty-four young women, from Lawrence, to the Stillman Farm, in Beverly.2, 11 All told, sixty-two young women vacationed at Stillman Farm, that first summer, enjoying the fresh air, open spaces and companionship.2 Although Helen monitored every detail of the management and organization, she hired a Mrs. Stefert, a family friend from Pittsburgh, to cook meals and run the home.2 Afternoons were spent swimming on the ocean beach at her family’s summer house, Eagle Rock, taking tea in the gardens, or going to Hamilton to watch a horse show or polo game, at the Myopia Hunt Club.2 One can only imagine how awestruck these young women were upon visiting the Eagle Rock summer home. It was a huge stone mansion, with over a hundred rooms, expansive gardens and a broad view of the Atlantic Ocean. -

Reading Guide in Sunlight, in a Beautiful Garden

Reading Guide In Sunlight, in a Beautiful Garden By Kathleen Cambor ISBN: 9780060007577 Johnstown, Pennsylvania 1889 So deeply sheltered and surrounded was the site that it was as if nature's true intent had been to hide the place, to keep men from it, to let the mountains block the light and the trees grow as thick and gnarled as the thorn-dense vines that inundated Sleeping Beauty's castle. Perhaps, some would say, years later, that was central to all that happened. That it was a city that was never meant to be. IntroductionOn May 31, 1889, the unthinkable happened. The dam supporting an artificial lake at the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, playground to wealthy and powerful financiers Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon, collapsed. It was one of the greatest disasters in post-Civil War America. Some 2,200 lives were lost in the Johnstown, Pennsylvania, flood. In the shadow of the Johnstown dam live Frank and Julia Fallon, devastated by the loss of two children; their surviving son, Daniel, a passionate opponent of industrial greed; Grace McIntyre, a newcomer with a secret; and Nora Talbot, a lawyer's daughter, who is both bound to and excluded from the club's society. As Frank and Julia, seemingly incapable of repairing their marriage, look to Grace for solace and friendship, Daniel finds himself inexplicably drawn to Nora, daughter of a wealthy family from Pittsburgh. James, Nora's father, struggles with his conscience after bending the law to file the club's charter and becomes increasingly concerned about the safety of the dam. -

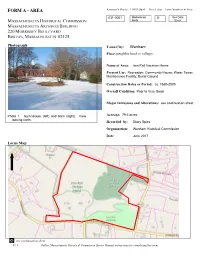

FORM a - AREA Assessor’S Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area

FORM A - AREA Assessor’s Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area 031-0001 Marblehead G See Data MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION North Sheet ASSACHUSETTS RCHIVES UILDING M A B 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Photograph Town/City: Wenham Place (neighborhood or village): Name of Area: Iron Rail Vacation Home Present Use: Recreation; Community House; Water Tower; Maintenance Facility; Burial Ground Construction Dates or Period: ca. 1880-2009 Overall Condition: Poor to Very Good Major Intrusions and Alterations: see continuation sheet Photo 1. Gymnasium (left) and barn (right). View Acreage: 79.6 acres looking north. Recorded by: Stacy Spies Organization: Wenham Historical Commission Date: June 2017 Locus Map see continuation sheet 4 /1 1 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM A CONTINUATION SHEET WENHAM IRON RAIL VACATION HOME MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area Letter Form Nos. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 G See Data Sheet Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. Use as much space as necessary to complete the following entries, allowing text to flow onto additional continuation sheets. ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION Describe architectural, structural and landscape features and evaluate in terms of other areas within the community. The Iron Rail Vacation Home property at 91 Grapevine Road is comprised of buildings and landscape features dating from the multiple owners and uses of the property over the 150 years. The extensive property contains shallow rises surrounded by wetlands. Woodlands are located at the north half of the property and wetlands are located at the northwest and central portions of the property. -

Four Mysterious Citizens of the United States That Served on The

Four Mysterious Citizens of the United States that Served On the International Olympic Com-mittee During the Period 1900-1917 Four Mysterious Citizens of the United States that Served On the International Olympic Com-mittee During the Period 1900-1917, Harvard University, William Milligan Sloane, Paris, Theodore Stanton, United States, America, American Olympic Committee, Olympic Games, Rutgers University, Pierre de Coubertin, International Olympic Committee, Karl Lennartz, Mr. Hyde, IOC member, Evert Jansen Wendell, Theodore Roosevelt, IOC members, Allison Vincent Armour, Olympic Research, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, New York, Messieurs Stanton, Caspar Whitney, Cornell University, William Howard Taft, Evert Jansen, John Updike, North American, The International Olympic Committee One Hundred Years, See Wolf Lyberg, French Foreign Legion, See Barbara Tuchman, Barrett Wendell, father Jacob, Allison V. Armour, George Armour, President Coubertin, American University Union, American Red Cross, Coubertin, Phillips Brooks, A. V. Armour, New York City, Harvard, See Roosevelt, Swedish Olympic Organizing Committee, E. J. Wendell, List of IOC members, Doctor Sloane, John A. Lucas, the United States, Professor W. M. Sloane, Pennsylvania State University, Modern Olympic Games, Henry Brewster Stanton, James Hazen Hyde, Theodore Weld Stanton, Evert Jansen Wendell John A. Lucas, Professor Emeritus William M. Sloane, Theodore Roosevelt Papers, New York Herald, Professor Sloane, James Haren Hyde, Stanton, Keith Jones, RUDL, Allison -

HAMPTON JITNEY MONTAUK Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

HAMPTON JITNEY MONTAUK bus time schedule & line map HAMPTON JITNEY MONTAUK 85th & Lexington- View In Website Mode Amagansett The HAMPTON JITNEY MONTAUK bus line (85th & Lexington-Amagansett) has 9 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) 85th & Lexington-Amagansett: 10:55 AM - 12:55 PM (2) 85th & Lexington-Montauk: 4:25 PM - 8:00 PM (3) Amagansett: 6:00 PM - 8:05 PM (4) Amagansett-Manhattan: 5:25 AM - 3:05 PM (5) Manhattan: 4:15 AM - 5:30 PM (6) Montauk: 8:30 AM - 10:50 PM (7) Southampton-Manhattan: 4:45 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest HAMPTON JITNEY MONTAUK bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next HAMPTON JITNEY MONTAUK bus arriving. Direction: 85th & Lexington-Amagansett HAMPTON JITNEY MONTAUK bus Time Schedule 9 stops 85th & Lexington-Amagansett Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:55 PM - 5:55 PM Monday 10:55 AM - 5:55 PM 85th St & Lexington Ave 131 East 85th Street, Manhattan Tuesday 10:55 AM - 12:55 PM 69th St Wednesday 10:55 AM - 12:55 PM 944 Lexington Ave, Manhattan Thursday 10:55 AM - 12:55 PM 59th St & Lexington Friday 10:55 AM - 12:55 PM 743 Lexington Avenue, Manhattan Saturday 12:55 PM 40th St 148 E 40 St, Manhattan Queens Airport Connection Eastbound 190-02 Horace Harding Expressway Sr S, Queens HAMPTON JITNEY MONTAUK bus Info Direction: 85th & Lexington-Amagansett Southampton Stops: 9 Trip Duration: 138 min Water Mill Eastbound Line Summary: 85th St & Lexington Ave, 69th St, 755 Montauk Highway, Water Mill 59th St & Lexington, 40th St, Queens Airport Connection Eastbound, Southampton, -

2009 Wooden Walk

2009 WOODEN WALK I. Matthew 1. Sullivan 30 Betsy Drive W. Sayville, NY 11796 2. SAME AS ABOVE 3. SAME AS ABOVE 4. Richard Coyne PO Box 903 , Sayville, NY 11782 5. Edward Candrava 55 Bay Walk POBox 5314 Fire Island, NY 6. Robert Felice PO Box 458 Ocean Beach, NY 11770 7. Pines Care Center, Inc. POBox 5333 Fire Island Pines, NY 11782 8. Danikki Inc. PO Box 408 Sayville, NY 11782 9. SAME AS ABOVE 10. Walter Boss 93 Block Duck Walk Fire Island Pines, NY 11782 11. SAME AS ABOVE 12. SAME AS ABOVE 13. SAME AS ABOVE 2009 WOODEN WALK 14, SAME AS ABOVE 15, SAME AS ABOVE 16, SAME AS ABOVE 17, SAME AS ABOVE 18, SAME AS ABOVE 19, Charles Quit 313 N. Titmus.Drive Manor Park, NY 11950 , 20, Matthew Cashman 10 Edwards Street Sayville, NY 11782 21, Robert C. Fair 93 Collins Avenue Sayville, NY 11782 22, Ganett Anger 15 Woodhull Landing Road Sound Beach, NY 11789 23, Paul Stoehrer 156 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 24, Kristine Pfoh 865 Broadway Avenue 227A Fire Island Pines, NY 11782 25, C. F. LaFountaine POBox 888 Sayville, l\Y 11782 26, SAME AS ABOVE 27, SAME AS ABOVE 28, SAME AS ABOVE 2009 WOODEN WALK 29. SAME AS ABOVE 30. SAME AS ABOVE 3l. SAME AS ABOVE 32. SAME AS ABOVE 33. SAME AS ABOVE 34. Robert G. Lerch 218 Beach Walk Cherry Grove, NY 11782 , 35. VOIDED 36. Eric Lebow 61 Country Club Road Bellport, NY 11713 37. SAME AS ABOVE 38. -

Historical Profile of Hampton Bays, Phase I

HISTORIC PROFILE OF HAMPTON BAYS Phase I GOOD GROUND MONTAUK HIGHWAY CORRIDOR and CANOE PLACE MONTAUK HIGHWAY, GOOD GROUND 1935 by Charles F. Duprez Prepared by: Barbara M. Moeller June 2005 Additional copies of the HISTORIC PROFILE OF HAMPTON BAYS: Phase I May be obtained through Squires Press POB 995 Hampton Bays, NY 11946 $25 All profits to benefit: The Hampton Bays Historical & Preservation Society HISTORIC PROFILE OF HAMPTON BAYS INTRODUCTION: The Town of Southampton has sponsored this survey of his- toric resources to complement existing and forthcoming planning initiatives for the Hamlet of Hampton Bays. A Hampton Bays Montauk Highway Corridor (Hamlet Centers) Study is anticipated to commence in the near future. A review of Hampton Bays history and an inventory of hamlet heritage resources is considered a necessary component in order to help insure orderly and coordinated development within the Hamlet of Hampton Bays in a manner that respects community character. Hampton Bays United, a consortium of community organizations, spearheaded the initiative to complete a historical profile for Hampton Bays and a survey of hamlet heritage re- sources. The 2000 Hampton Bays Hamlet Center Strategy Plan adopted as an update to the 1999 Comprehensive Plan was limited to an area from the railroad bridge tres- tle on Montauk Highway near West Tiana Road (westerly border) to the Montauk Highway railroad bridge near Bittersweet Avenue (easterly border.) Shortly, the De- partment of Land Management will be preparing a “Hampton Bays Montauk High- way Corridor Land Use/Transportation Strategy Study” which will span the entire length of Montauk Highway from Jones Road to the Shinnecock Canal. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Voices from the Field

Voices from the Field Voices from the Field Prohibition, war bonds, the formation of social security—the National Association of Insurance and Financial Advisors has seen it all. In August 1989, the National Association of Life Underwriters—later to be renamed NAIFA— published Voices from the Field, a seminal work chronicling the history of the insurance industry and the association. This book was the result of four years of research and writing by former Advisor Today senior editor George Norris. Voices from the Field is an engaging look at the lives and events that shaped our dynamic industry. The book remains a lasting tribute to everyone who has worked to make NAIFA what it is today, but particularly to Norris, who dedicated 21 years to the association. *** “Historians have, perhaps, been too preoccupied with mortality tables and the founding dates of companies to consider the astonishing influence that selling method, or the lack of it, has had upon the development of life insurance in every age.” —J. Owen Stalson, Marketing Life Insurance: Its History in America This book is dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of unnamed and often unsung, life underwriters who, over the past 100 years, have labored to provide security and financial independence to millions of their fellow Americans. Foreword by Alan Press, 1988-1989 NALU President Preface by Jack E. Bobo, 1989 NALU Executive Vice President Introduction Acknowledgements Chapter 1 Laying the Foundation—A Meeting at the Parker House Leading Figures—Ransom, Carpenter, Blodgett and -

John Quinn, Art Advocate

John Quinn, Art Advocate Introduction Today I’m going to talk briefly about John Quinn (fig. 1), a New York lawyer who, in his spare time and with income derived from a highly-successful law practice, became “the twentieth century’s most important patron of living literature and art.”1 Nicknamed “The Noble Buyer” for his solicitude for artists as much as for the depth of his pocketbook, Quinn would amass an unsurpassed collection of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American and European art. At its zenith, the collection con- tained more than 2,500 works of art, including works by Con- stantin Brancusi, Paul Cézanne, André Derain, Marcel Du- champ, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Paul Gaugin, Juan Gris, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Rouault, Henri Rousseau, Georges Seurat, and Vincent van Gogh.2 More than a collector, Quinn represented artists and art associa- tions in all types of legal matters. The most far-reaching of these en- gagements was Quinn’s successful fight for repeal of a tariff on im- 1 ALINE B. SAARINEN, THE PROUD POSSESSORS: THE LIVES, TIMES AND TASTES OF SOME ADVENTUROUS AMERICAN ART COLLECTORS 206 (1958) [hereinafter PROUD POSSESSORS]. 2 Avis Berman, “Creating a New Epoch”: American Collectors and Dealers and the Armory Show [hereinafter American Collectors], in THE ARMORY SHOW AT 100: MODERNISM AND REVOLUTION 413, 415 (Marilyn Satin Kushner & Kimberly Orcutt eds., 2013) [hereinafter KUSHNER & ORCUTT, ARMORY SHOW] (footnote omitted). ported contemporary art3 – an accomplishment that resulted in him being elected an Honorary Fellow for Life by the Metropolitan Mu- seum of Art.4 This work, like much Quinn did for the arts, was un- dertaken pro bono.5 Quinn was also instrumental in organizing two groundbreaking art exhibitions: the May 1921 Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition of “Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings” (that museum’s first exhibition of modern art),6 and the landmark 1913 “International Exhibition of Modern Art”7 – otherwise known as the Armory Show. -

The Inventory of the Everett Raymond Kinstler Collection #1705

The Inventory of the Everett Raymond Kinstler Collection #1705 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Kinstler, Everett Raymond #1705 8/9/05 Preliminary Listing I. Printed Material. Box 1 A. Chronological files; includes news clippings, periodicals, bulletins, and other items re: ERK and his artwork. 1. "1960-62." [F. 1] 2. "1963-64," includes photos. [F. 2] 3. "1965-66." [F. 3] 4. "1967-68." [F. 4] 5. "1969." [F. 5] 6. "1970." [F. 6] 7. "1971," includes photos. [F. 7] 8. "1972," includes photos. [F. 8] 9. "1973." [F. 9] 10. "1974." [F. 10] 11. "1975." [F. 11] 12. "1976." [F. 12] 13. "1977." [F. 13] 14. "1978." [F. 14] 15. "1979." [F. 15] Box2 16. "1980." [F. 1-2] 17. "1981." [F. 3-4] 18. "1982." [F. 5-6] 19. "1983." [F. 7] 20. "1984." [F. 8] 21. "1985." [F. 9] 22. "1986." [F. 10] 23. "1987." [F. 11] 24. "1988." [F. 12] 25. "1988-89." [F. 13] 26. "1990." [F. 14] 27. "1991." [F. 15] Box3 28. "1992." [F. 1] 29. "1993." [F. 2] 30. "1994." [F. 3] 31. "1995." [F. 4] 32. "1996." [F. 5] 33. "1997." · [F. 6] 34. "1998." [F. 7] 35. "1999." [F. 8] 36. "2000." [F. 9] Kinstler, Raymond Everett (8/9/05) Page 1 of 38 37. "2001." [F. 10-11] 38. "2002." [F. 12-13] 39. "2003." [F. 14] 40. "2004." [F. 15-16] II Correspondence. Box4 A. Letters to ERK arranged alphabetically; includes some responses from ERK. 1. Adams, James F. TLS, 5/16/62. [F. 1] 2. Adams,(?). ALS, Aug. -

1848 George A

Methuen Jan. 4 1848 George A. Waldo Selectmen Joseph How } of Moses L. Atkinson Methuen A true copy Attest Josiah Dearborn Town Clerk. 1848 March 6, 1848 – Annual Meeting Annual meeting of the inhabitants of the Town of Methuen qualified by law to vote in Town Affairs held on Monday March the sixth 1848, agreeable to Warrant 62 File 6th Opened said meeting at ten O’clock A.M. Article 1st Chose George A. Waldo Moderator Prayer by Reverend Joseph M. Graves. Article 2nd Chose Josiah Dearborn Town Clerk. Sworn Voted that the number of Selectmen for the year ensuing, shall consist of three. Whole number of ballots for Selectmen was 290 – Necessary for choice 146 George A. Waldo had 174 votes and was chosen (sworn) Frederick Kimball had 157 votes and was chosen (sworn) No other person had a sufficient number of ballots to elect him, therefore it was Voted to adjourn for one hour. 2d Ballot for Selectmen – Whole number of ballots was 239 – Necessary for choice 120. John W. Hall had 150 and was elected/Sworn School Committee Report was read, accepted and the usual number was Voted to be printed under the direction of the School Committee. Voted that the number of the School Committee shall consist of three School Committee - Stephen Huse, Daniel Merrill 2d & O. H. Tillotson were elected. Constables. Voted that the number consist of two. John Low and Charles E. Goss were elected & sworn. Treasurer. Josiah Dearborn was elected. Collector. Josiah Dearborn was elected. Fire Wardens chosen. John Low, Kimball C. Gleason, Charles Ingalls, Daniel Merrill 3d, Frederick George.