Mental Health in Minnesota DATA BRIEF: 2016 CSTE MENTAL HEALTH INDICATORS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Physical, Sexual, and Psychological Aggression

University of Kentucky UKnowledge CRVAW Faculty Journal Articles Center for Research on Violence Against Women 4-2010 Violence and Women’s Mental Health: The mpI act of Physical, Sexual, and Psychological Aggression Carol E. Jordan University of Kentucky, [email protected] Rebecca Campbell Michigan State University Diane R. Follingstad University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/crvaw_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Family Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, and the Social Work Commons Repository Citation Jordan, Carol E.; Campbell, Rebecca; and Follingstad, Diane R., "Violence and Women’s Mental Health: The mpI act of Physical, Sexual, and Psychological Aggression" (2010). CRVAW Faculty Journal Articles. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/crvaw_facpub/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Research on Violence Against Women at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in CRVAW Faculty Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Violence and Women’s Mental Health: The Impact of Physical, Sexual, and Psychological Aggression Notes/Citation Information Published in Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, v. 6, p. 607-628. Digital Object Identifier (DOI) http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-090209-151437 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/crvaw_facpub/7 ANRV407-CP06-01 ARI 10 November 2009 12:13 V I E E W R S I E N C N A D V A Violence and Women’s Mental Health: The Impact of Physical, Sexual, and Psychological Aggression Carol E. -

Understanding the Relationship Between Mental Health & Mental

Understanding the Relationship Between Mental Health & Mental Illness Module 2 UNDERSTANDING MENTAL HEALTH STATES: WHAT THE WORDS MEAN The Inter-Relationship of Mental Health States Depression Mental Disorder/Illness Heartbroken, sorrowful, demoralized, grieving, mournful, despairing Mental Health Problem Upset, annoyed, sad, unhappy, disappointed, disgusted, angry, bitter, blue, down, sorry, Mental Distress glum, forlorn, disconsolate, distressed, despondent, dejected, pessimistic Pensive, thoughtful No Distress, Problem or Disorder MENTAL DISTRESS • The brain’s expected and usual response to the stresses of everyday life (e.g. exams, relationships, disappointments) • Happens to everyone every day • Leads to adaptation, learning and coping • Is often seen as negative instead of as helpful • Must reframe as positive (excitement not stress) • Does not need treatment MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEM •The brain’s response to a severe or persistent life problem (e.g. death of a family member, severe bullying, parent divorce) • Happens to everyone many times in their life • Shows that adaptation is difficult • May require additional help (such as a counsellor or therapist) • Does not require treatment MENTAL DISORDER •The brain is not functioning as it is supposed to function, leading to significant and persistent problems in a person’s everyday life (caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors) • Happens to about 20% of people over their lifetime • Must be diagnosed by a properly trained health professional • Requires scientifically valid treatments provided by a trained health professional ALL TOGETHER • A person can be in one or more of these mental health states at the same time! • For example: a person can have Schizophrenia (a mental disorder), their mother has recently died (a mental health problem), they lost their car keys earlier today (mental distress) and now they are hanging out with a friend and enjoying themselves. -

DISTRESS AMONG PSYCHOLOGISTS: PREVALENCE, BARRIERS, and REMEDIES for ACCESSING MENTAL HEALTH CARE a Dissertation Presented to T

DISTRESS AMONG PSYCHOLOGISTS: PREVALENCE, BARRIERS, AND REMEDIES FOR ACCESSING MENTAL HEALTH CARE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Antioch University Seattle Seattle, WA In partial fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Psychology By Kimberly G. Patterson-Hyatt August 2016 DISTRESS AMONG PSYCHOLOGISTS: PREVALENCE, BARRIERS, AND REMEDIES FOR ACCESSING MENTAL HEALTH CARE This dissertation, by Kimberly G. Patterson-Hyatt, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of the Antioch University Seattle at Seattle, WA in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: ______________________________ Mark Russell, Ph.D., ABPP Chairperson ______________________________ Bill Heusler, Psy.D. ______________________________ Colin Ward, Ph.D. ______________________________ Date ii © Copyright by Kimberly Patterson-Hyatt, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii 1 ABSTRACT DISTRESS AMONG PSYCHOLOGISTS: PREVALENCE, BARRIERS, AND REMEDIES FOR ACCESSING MENTAL HEALTH CARE Kimberly G. Patterson-Hyatt Antioch University Seattle Seattle, WA This study completed a critical review of psychologists’ mental health by developing a conceptual analysis based on the current empirical literature of the mental health needs of clinical psychologists. Distress among psychologists was explored by examining the following domains: (a) examining the prevalence of mental illness and psychological distress that exist among them, (b) examining the barriers they encounter to seeking treatment when experiencing this distress, and (c) reviewing current interventions and integrating remedies for access to mental health care that best meets psychologists’ needs. Results included several themes within each domain shaping a contextual picture of some of the challenges faced by psychologists and gaps that need to still be further addressed. -

Substance Use and Symptoms of Mental Health Disorders: A

Aas et al. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy (2021) 16:20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-021-00354-1 RESEARCH Open Access Substance use and symptoms of mental health disorders: a prospective cohort of patients with severe substance use disorders in Norway Christer Frode Aas1,2* , Jørn Henrik Vold1,2, Rolf Gjestad3, Svetlana Skurtveit4,5, Aaron Guanliang Lim6, Kristian Varden Gjerde3, Else-Marie Løberg1,3,7, Kjell Arne Johansson1,2, Lars Thore Fadnes1,2 and for the INTRO-HCV Study Group Abstract Background: There is high co-occurrence of substance use disorders (SUD) and mental health disorders. We aimed to assess impact of substance use patterns and sociodemographic factors on mental health distress using the ten- item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-10) over time. Methods: Nested prospective cohort study of 707 participants with severe SUD across nine opioid-agonist-therapy outpatient clinics and low-threshold municipality clinics in Norway, during 2017–2020. Descriptive statistics were derived at baseline and reported by means and standard deviation (SD). A linear mixed model analysis was used to assess the impact of substance use patterns and sociodemographic factors on SCL-10 sum score with beta coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Results: Mean (SD) SCL-10 score was 2.2 (0.8) at baseline with large variations across patients. We observed more symptoms of mental health disorders among people with frequent use of benzodiazepines (beta 3.6, CI:2.4;4.8), cannabis (1.3, CI:0.2;2.5), opioids (2.7, CI:1.1;4.2), and less symptoms among people using frequent stimulant use (− 2.7, CI:-4.1;-1.4) compared to no or less frequent use. -

Poverty and Mental Health

Poverty and mental health A review to inform the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s Anti-Poverty Strategy 1 POLICY REVIEW AUGUST 2016 Poverty and Mental Health: A review to inform the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s Anti-Poverty Strategy Iris Elliott PhD FRSA August 2016 Citation The recommended citation for this review is: Elliott, I. (June 2016) Poverty and Mental Health: A review to inform the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s Anti-Poverty Strategy. London: Mental Health Foundation. Acknowledgements Helen Barnard managed the delivery of the review for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and co-ordinated input from her colleagues. Professor David Pilgrim, University of Liverpool; Professor David Kingdon, University of Southampton; Andy Bell, Centre for Mental Health; and Sam Callan, Centre for Social Justice were insightful reviewers. Thank you to the Mental Health Foundation team who supported the writing of this report: Isabella Goldie, Director of Development and Delivery; Marguerite Regan, Policy Manager; and Laura Bernal, Policy Officer. 2 3 Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................7 2. Poverty and Mental Health: A Conceptual Framework ...................................15 3. Poverty and Mental Health Across the Life Course ..........................................22 4. Public Services ............................................................................................................................32 -

Suppor†Ing Older People Who Are Experiencing Men†Al Dis†Ress Or Living Wi†H a Men†Al Illness

RESEARCH TO PRACTICE Supporting older people BRIEFING 7 who are experiencing mental distress or living with a mental illness Mental distress or illness is not a normal part of ageing. However, like people of any age, older people can be vulnerable to mental illness. Some older people develop a mental illness as they age, while others grow older with a continuing experience of a mental illness that developed earlier in their lives. This briefing reviews the research on the symptoms and treatments of mental illness in older people. It focuses on how those in the community aged care sector (including care workers, case managers, team leaders, and managers) can support people who show signs of mental illness. Research to Practice Briefings Research to Practice Briefings bring together lessons learned from the literature on a topical issue in community aged care as a resource for those working in this sector. As in most areas of social policy and practice, the research evidence on community care is continually evolving. The Briefings aim to distil key themes and messages from the research and to point to promising and innovative practices. An advisory group of academics and expert practitioners working in the area of aged care provide advice and peer review. This briefing has been prepared by the National Ageing Research Institute (NARI) in partnership with The Benevolent Society. www.benevolent.org.au Research to Practice Briefing 7 Overview of mental health residential aged care (Ostling & Skoog, 2002). Risk and older people factors for depression in older people include the loss of relationships, independence and physical Mental health has been defined as the embodiment function; social isolation; bereavement; changes in of social, emotional and spiritual wellbeing (VicHealth, living arrangements; chronic pain and other health 2005). -

Understanding Your Mental Wellbeing

Understanding Your Mental Wellbeing A Brief Introduction to the Science of Mental Wellbeing This workbook is uncopyrighted. Please feel free to share it on your website with an attribution and a link to our website. CONTENTS 1 Problems With the Current Approach to Mental Health 2 Causes of Poor Mental Wellbeing 5 Parenting Styles Associated with Poor Mental Wellbeing 6 How Poor Parenting Affects Your Relationships 8 The Subordinate Approval Trap 9 Dr Paul Gilbert's Evolutionary Model of Mental Wellbeing 11 Your Personal Signs of Poor Mental Wellbeing 12 Understanding Panic Attacks 13 How to Improve Your Mental Wellbeing THE WELLNESS SOCIETY PROBLEMS WITH THE CURRENT APPROACH TO MENTAL HEALTH Common mental health problems outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) include: » Depression » Generalised anxiety disorder » Social anxiety disorder » Panic disorder » Phobias » Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) This language of ‘disorders’ – the medical/disease model – has been heavily criticised for a long time. “Deeply flawed and scientifically unsound.” – Professor Allen Frances, the Chair of the DSM-4 committee “Totally wrong, an absolute scientific nightmare.” - Dr Steven Hyman, former National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) director “It undermines genuine empathy and compassion; instead of seeing the people’s difficulties as understandable and natural responses to terrible things that have happened to them, the person is seen as having something wrong with them – an ‘illness’.” – Professor Peter Kinderman, former Vice-President of the British Psychological Society (BPS) The NHS website also outlines two main criticisms of the current diagnostic approach: 1. -

The Twentieth Century Revolutions in Psychiatry, Law and Public

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Faculty Articles and Essays Faculty Scholarship 2003 Looking Backward: The weT ntieth Century Revolutions in Psychiatry, Law and Public Mental Health Sheldon Gelman Cleveland State University, [email protected] How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/fac_articles Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Law and Psychology Commons Original Citation Sheldon Gelman, Looking Backward: The wT entieth Century Revolutions in Psychiatry, Law and Public Mental Health, 29 Ohio Northern University Law Review 531 (2003) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Articles and Essays by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 29 Ohio N.U. L. Rev. 531 2002-2003 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Fri Sep 28 09:59:20 2012 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0094-534X Looking Backward: The Twentieth Century Revolutions in Psychiatry, Law, and Public Mental Health SHELDON GELMAN* I. -

Clinical Implications of Compassion Fatigue

Psychiatria Danubina, 2015; Vol. 27, Suppl. 1, pp 321–327 Conference paper © Medicinska naklada - Zagreb, Croatia PSYCHIATRIC CAREGIVER STRESS: CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS OF COMPASSION FATIGUE Francesco Franza1, Gianfranco Del Buono2 & Ferdinando Pellegrino3 1Neuropsychiatric Centre “Villa dei Pini”, Avellino, Italy 2Division Psychiatry, "S. Giovanni di Dio and Ruggi D'Aragona Hospital, University Salerno, Salerno, Italy 3Mental Health Department, Salerno, Italy SUMMARY The capacity to work productively is a key component of health and emotional well-being. People who work in health care can be exposed to the fatigue of care. Compassion fatigue has been described as an occupational hazard specific to clinical work related severe emotional distress. In our study, we have evaluated compassion fatigue in a mental health group (47 psychiatric staff) and its relationship with inpatients (237 inpatients) affected by some psychiatric disorders. At baseline, the more significant data indicate a high percentage of Job Burnout and Compassion Fatigue in psychiatric nurses (respectively, 39.28%, 28.57%). Significant Compassion Fatigue percentage is present also in psychologist group (36.36%). Finally, in psychiatrists, the exposure to patients increased vicarious trauma (28.57%), but not job burnout. After a year of participation in Balint Groups, the psychiatric staff presented an overall reduction in total mean score in any administered scale (CBI: p<0.0000045; sCFs: (Vicarious Trauma: p<0.0288; Job Burnout: p<0.000001)). Thus, compassion fatigue causes concern among mental health professionals, and Balint Groups may represent a therapeutic strategy to help health professionals to face difficulties in challenging work environments. Key words: compassion fatigue – burnout – psychiatric caregivers * * * * * INTRODUCTION majority of workplace health programs (Tan 2014). -

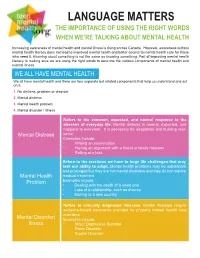

Language Matters the Importance of Using the Right Words When We’Re Talking About Mental Health

LANGUAGE MATTERS THE IMPORTANCE OF USING THE RIGHT WORDS WHEN WE’RE TALKING ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH Increasing awareness of mental health and mental illness is rising across Canada. However, awareness without mental health literacy does not lead to improved mental health and better access to mental health care for those who need it. Knowing about something is not the same as knowing something. Part of improving mental health literacy is making sure we are using the right words to describe the various components of mental health and mental illness. WE ALL HAVE MENTAL HEALTH We all have mental health and there are four separate but related components that help us understand and act on it. 1. No distress, problem or disorder 2. Mental distress 3. Mental health problem 4. Mental disorder / illness Refers to the common, expected, and normal response to the stresses of everyday life. Mental distress is normal, expected, and happens to everyone. It is necessary for adaptation and building resil- ience. Mental Distress Examples include: • Writing an examination • Having an argument with a friend or family member • Failing at a task Refers to the reactions we have to huge life challenges that may task our ability to adapt. Mental health problems may be substantial and prolonged but they are not mental disorders and they do not require Mental Health medical treatment Problem Examples include: • Dealing with the death of a loved one • Loss of a relationship, such as divorce • Moving to a new country Refers to clinically diagnosed illnesses. Mental illnesses require evidence-based treatments provided by properly trained health care providers. -

Self-Medication

Self-medication This article is about drug use without supervision of a them achieve emotional stability.[8][9] physician. For the operant conditioning concept, see The self-medication hypothesis (SMH) originated in pa- Self-administration. For other uses, see Self-medication pers by Edward Khantzian, Mack and Schatzberg,[10] (disambiguation). David F. Duncan,[11] and a response to Khantzian by Duncan.[12] The SMH initially focused on heroin use, but Self-medication is a human behavior in which an in- a follow-up paper added cocaine.[13] The SMH was later dividual uses a substance or any exogenous influence to expanded to include alcohol,[14] and finally all drugs of self-administer treatment for physical or psychological addiction.[8][15] ailments. According to Khantzian’s view of addiction, drug users The most widely self-medicated substances are over-the- compensate for deficient ego function[10] by using a drug counter drugs and dietary supplements. The psychology as an “ego solvent”, which acts on parts of the self that are of self-medicating with psychoactive drugs is typically cut off from consciousness by defense mechanisms.[8] Ac- within the specific context of using recreational drugs, cording to Khantzian,[13] drug dependent individuals gen- alcohol, comfort food, and other forms of behavior erally experience more psychiatric distress than non-drug to alleviate symptoms of mental distress, stress and dependent individuals, and the development of drug de- anxiety,[1] including mental illnesses and/or psychological pendence involves the gradual incorporation of the drug trauma,[2][3] is particularly unique and can serve as a seri- effects and the need to sustain these effects into the defen- ous detriment to physical and mental health if motivated sive structure-building activity of the ego itself. -

Position/Policy Statement Supporting Mental Health in the Workplace

# 163 NATIONAL SAFETY COUNCIL Position/Policy Statement Supporting Mental Health in the Workplace Policy/Position: The National Safety Council supports actions by stakeholders on the federal, state and local levels, in addition to employers and other organizations, to advance the following initiatives that support mental health as part of overall health. Given the amount of time people spend in their workplace, leveraging employers and the workplace is a key strategy for addressing mental health. NSC acknowledges that several factors influence mental health and wellbeing, and as a workplace-focused organization, this policy position will address the role of workplaces and employers to support mental health and wellbeing. Mental health, wellbeing and illness are critical components of worker health and wellbeing. Workplaces should prioritize protecting employees’ mental health and safety on an equal level with physical safety. Addressing mental health in the workplace requires continuous leadership and commitment from leaders, buy-in from managers, supervisors and employees, compassionate and flexible policies and programs, facilitating education, awareness and a strong understanding and respect for the complexities of mental health, wellbeing and illness from the top down. The National Safety Council recommends taking action in four categories. 1. Strengthening Prevention Interventions and Treatment Accessibility 2. Actions for Leadership and Supervisors – Prioritizing Mental Health 3. Actions for Human Resources – Developing Policies, Procedures and Programs to Support Mental Health 4. Providing Employee Education and Awareness Background Both mental health distress and mental illness, including general symptoms of depression, anxiety, substance use and stress as well as diagnosable conditions, are common, affecting individuals, their families, co-workers and the broader community.