Physical and Social Spaces 'Under Construction' Spatial and Ethnic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT December

Xinjiang Aksu San Jiang Breeding Co., Ltd CDM Biogas Power Generation Project Environmental Impact Report E2027 Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized December 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized 6XUYH\LQJ3ODQQLQJDQG'HVLJQLQJ5HVHDUFK,QVWLWXWHRI;LQMLDQJ 3URGXFWLRQ &RQVWUXFWLRQ&RUSV Public Disclosure Authorized 6XUYH\LQJÃ3ODQQLQJÃDQGÃ'HLVJQLQJÃ5HVHDUFKÃ,QVWLWXWHÃRIÃ;LQMLDQJÃ3URGXFWLRQÃÉÃ&RQVWUXFWLRQÃ&RUSVÃ -1-Ã Xinjiang Aksu San Jiang Breeding Co., Ltd CDM Biogas Power Generation Project Environmental Impact Report Content Foreword..................................................................................................................... 7 1General Provisions .................................................................................................... 9 1.1Preparation basis.................................................................................................................9 1.2 Evaluation Principle and Preparation Purpose ..................................................................11 1.3 Evaluation key point and evaluation class ........................................................................12 1.4 Evaluation range and standard..........................................................................................15 1.5 Environmental protection target .......................................................................................18 2. General Situation of Regional Environment .......................................................... 19 2.1 -

Forced Labour in East Turkestan: State-Sanctioned Hashar System

FORCED LABOUR IN EAST TURKESTAN: State -Sanctioned Hashar System World Uyghur Congress | November 2016 WUC Headquarters: P.O. Box 310312 80103 Munich, Germany Tel: +49 89 5432 1999 Fax: +49 89 5434 9789 Email: [email protected] Web Address: www.uyghurcongress.org Copyright © 2016 World Uyghur Congress All rights reserved. The World Uyghur Congress (WUC) is a n international organization that represents the collective interests of the Uyghur people in both East Turkestan and abroad. The principle objective of the WUC is to promote democracy, human rights and freedom for the Uyghur people and use peaceful, nonviolent and democratic means to determine their future. Acting as the sole legitimate organization of the Uyghur people in both East Turkestan and abroad, WUC endeavors to set out a course for the peaceful settlement of the East Turkestan Question through dialogue and negotiation. The WUC supports a nonviolent and peaceful opposition movement against Chinese occupation of East Turkestan and an unconditional adherence to internationally recognized human rights standards as laid down in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It adheres to the principles of democratic pluralism and rejects totalitarianism, religious intolerance and terrorism as an instrument of policy. For more information, please visit our website: www.uyghurcongress.org Cover Photo: Uyghurs performing forced labour under the hashar system in Aksu Prefecture, East Turkestan (Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service). FORCED LABOUR IN EAST TURKESTAN: State-Sanctioned Hashar System EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The importance of the protection of human rights has been trending downward under China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, since he took power in 2013. -

Uyghur Experiences of Detention in Post-2015 Xinjiang 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................9 METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................10 MAIN FINDINGS Surveillance and arrests in the XUAR ................................................................................13 Surveillance .......................................................................................................................13 Arrests ...............................................................................................................................15 Detention in the XUAR ........................................................................................................18 The detention environment in the XUAR ............................................................................18 Pre-trial detention facilities versus re-education camps ......................................................20 Treatment in detention facilities ..........................................................................................22 Detention as a site of political indoctrination and cultural cleansing....................................25 Violence in detention facilities ............................................................................................26 Possibilities for information -

Employment and Labor Rights in Xinjiang

Employment and Labor Rights in Xinjiang The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China September 2020 1 Contents Preface I. Employment in Xinjiang II. Proactive Employment Policies III. Full Respect for Workers’ Job Preferences IV. Labor Rights Protection V. Better Jobs for Better Lives VI. Application of International Labor and Human Rights Standards Conclusion 2 Preface Work creates the means of existence and is an essential human activity. It creates a better life and enables all-round human development and the progress of civilization. The Constitution of the People’s Republic of China provides that all citizens have the right and obligation to work. To protect the right to work is to safeguard human dignity and human rights. China has a large population and workforce. Employment and job security are key to guaranteeing workers’ basic rights and wellbeing, and have a significant impact on economic development, social harmony, national prosperity, and the nation’s rejuvenation. China is committed to the people-centered philosophy of development, attaches great importance to job security, gives high priority to employment, and pursues a proactive set of policies on employment. It fully respects the wishes of workers, protects citizens’ right to work in accordance with the law, applies international labor and human rights standards, and strives to enable everyone to create a happy life and achieve their own development through hard work. In accordance with the country’s major policies on employment and the overall plan for eliminating poverty, the 3 Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region takes the facilitation of employment as the most fundamental project for ensuring and improving people’s wellbeing. -

Sacred Right Defiled: China’S Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom

Sacred Right Defiled: China’s Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom A Report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project Table of Contents Executive Summary...........................................................................................................2 Methodology.......................................................................................................................5 Background ........................................................................................................................6 Features of Uyghur Islam ........................................................................................6 Religious History.....................................................................................................7 History of Religious Persecution under the CCP since 1949 ..................................9 Religious Administration and Regulations....................................................................13 Religious Administration in the People’s Republic of China................................13 National and Regional Regulations to 2005..........................................................14 National Regulations since 2005 ...........................................................................16 Regional Regulations since 2005 ..........................................................................19 Crackdown on “Three Evil Forces”—Terrorism, Separatism and Religious Extremism..............................................................................................................23 -

Water Scarcity and Allocation in the Tarim Basin: Decision Structures and Adaptations on the Local Level Niels THEVS

● ● ● ● Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 3/2011: 113-137 Water Scarcity and Allocation in the Tarim Basin: Decision Structures and Adaptations on the Local Level Niels THEVS Abstract: The Tarim River is the major water source for all kinds of human activities and for the natural ecosystems in the Tarim Basin, Xin- jiang, China. The major water consumer is irrigation agriculture, mainly cotton. As the area under irrigation has been increasing ever since the 1950s, the lower and middle reaches of the Tarim are suffering from a water shortage. Within the framework of the Water Law and two World Bank projects, the Tarim River Basin Water Resource Commission was founded in 1997 in order to foster integrated water resource manage- ment along the Tarim River. Water quotas were fixed for the water utili- zation along the upstream and downstream river stretches. Furthermore, along each river stretch, quotas were set for water withdrawal by agricul- ture and industry and the amount of water to remain for the natural ecosystems (environmental flow). Furthermore, huge investments were undertaken in order to increase irrigation effectiveness and restore the lower reaches of the Tarim River. Still, a regular water supply for water consumers along the Tarim River cannot be ensured. This paper thus introduces the hydrology of the Tarim River and its impacts on land use and natural ecosystems along its banks. The water administration in the Tarim Basin and the water allocation plan are elaborated upon, and the current water supply situation is discussed. Finally, the adaptations made due to issues of water allocation and water scarcity on the farm level are investigated and discussed. -

China COI Compilation-March 2014

China COI Compilation March 2014 ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation China COI Compilation March 2014 This COI compilation does not cover the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, nor does it cover Taiwan. The decision to exclude Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan was made on the basis of practical considerations; no inferences should be drawn from this decision regarding the status of Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan. This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared on the basis of publicly available information, studies and commentaries within a specified time frame. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. -

China's Far West: Conditions in Xinjiang One Year After

CHINA’S FAR WEST: CONDITIONS IN XINJIANG ONE YEAR AFTER DEMONSTRATIONS AND RIOTS ROUNDTABLE BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 19, 2010 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 57–904 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 17:20 Oct 27, 2010 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\57904.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page Opening statement of Charlotte Oldham-Moore, Staff Director, Congressional- Executive Commission on China ........................................................................ 1 Kan, Shirley A., Specialist in Asian Security Affairs, Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division, Congressional Research Service ....................................... 2 Toops, Stanley W., Associate Professor, Department of Geography and Inter- national Studies Program, Miami University .................................................... 5 Richardson, Sophie, Asia Advocacy Director, Human Rights Watch .................. 8 APPENDIX PREPARED STATEMENT Toops, Stanley W. .................................................................................................... 28 SUBMISSIONS FOR THE RECORD Prepared Statement -

1 Racism, Religion and Governmentality In

Racism, religion and governmentality in China the Muslim rebellion in the 19th century Yuehua Dong Field of study: Religion in Peace and Conflict Level: Master Credits: 30 credits Thesis Defense: Spring 2016 Supervisor: Mattias Gardell Department of Theology Uppsala University 1 Abstract: This thesis consists of historical narratives on Muslim rebellion (1864-1877) in Xinjiang together with several parts of theoretical applications on racial-culturalism, nationalism, governmentality and further discussion on colonialism in the 19th century of China. By taking this 14 years’ historical event as a prototype, with analysis on historical archives, thesis has explored lots of issues which reflect ethnic conflicts on religion, racial-culturalism and governmentality on Xinjiang. With discourse analysis as leading method in analyzing original archives, this thesis depicts racial notions as “shengfan (raw barbarian)”, “shufan (cooked barbarian)” as core opinions in rulers’ political colonial view, hence formed Chinese unification and national identity and even influenced on governmentality in Xinjiang in Qing dynasty. And this vigilance of Qing rulers came from a mixed political consideration which combined islamophobia with frontier security issues. The results of the analysis indicate that there are three features from the events within the empiric materials’ analysis: there was strong evidence to present Qing rulers’ political discourse on ethnocentric view also with racial cultural superiority; the formation of Chinese nationalism was changed with enlarging territory; defects in Qing’s governmentality in Xinjiang became a blasting fuse which led to rebellion. By this researching conclusion, this paper provides more inspirations and indications on perspectives like cultural differences, Qing’s governmentality, frontier security and unification thought in rulers since ancient times. -

Family De-Planning: the Coercive Campaign to Drive Down Indigenous Birth-Rates in Xinjiang 1

Family de-planning The coercive campaign to drive down indigenous birth-rates in Xinjiang Nathan Ruser and James Leibold S OF AS AR PI E S Y T Y R T A T N E E G Y W T Policy Brief 2 0 1 01 - 20 2 Report No. 44/2021 About the authors Nathan Ruser is a researcher with ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre. James Leibold is a non-resident Senior Fellow with ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre. Acknowledgements We would like to thank our external peer reviewers, Dr Timothy Grose, Dr Adrian Zenz, Dr Stanley Toops, and Peter Mattis, for their comments and helpful suggestions. Darren Byler, Timothy Grose and Vicky Xu also generously shared with us a range of primary source materials. We’re also grateful for the comments and assistance provided within ASPI by Michael Shoebridge, Fergus Hanson, Danielle Cave, Kelsey Munro and Samantha Hoffman and for crucial research assistance from Tilla Hoja and Daria Impiombato. This research report forms part of the Xinjiang Data Project, which brings together rigorous empirical research on the human rights situation of Uyghurs and other non-Han nationalities in the XUAR. It focuses on a core set of topics, including mass internment camps; surveillance and emerging technologies; forced labour and supply chains; the CCP’s “re-education” campaign and deliberate cultural destruction and other human rights issues. The Xinjiang Data Project is produced by researchers at ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) in partnership with a range of global experts who conduct data-driven, policy-relevant research. -

A Spatial Analysis

RESEARCH ARTICLE Socio-Demographic Predictors and Distribution of Pulmonary Tuberculosis (TB) in Xinjiang, China: A Spatial Analysis Atikaimu Wubuli1,5, Feng Xue2, Daobin Jiang3, Xuemei Yao1, Halmurat Upur4*, Qimanguli Wushouer3* 1 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China, 2 Center for Tuberculosis Control and Prevention, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China, 3 Department of Respiratory Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China, 4 Department of Traditional Uygur Medicine, Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China, 5 Research Institution of Health Affairs Development and Reform, Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China * [email protected] (HU); [email protected] (QW) OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Wubuli A, Xue F, Jiang D, Yao X, Upur H, Wushouer Q (2015) Socio-Demographic Predictors and Distribution of Pulmonary Tuberculosis (TB) in Objectives Xinjiang, China: A Spatial Analysis. PLoS ONE 10 Xinjiang is one of the high TB burden provinces of China. A spatial analysis was conducted (12): e0144010. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144010 using geographical information system (GIS) technology to improve the understanding of Editor: Antonio Guilherme Pacheco, FIOCRUZ, geographic variation of the pulmonary TB occurrence in Xinjiang, its predictors, and to BRAZIL search for targeted interventions. Received: January 6, 2015 Accepted: November 12, 2015 Methods Published: December 7, 2015 Numbers of reported pulmonary TB cases were collected at county/district level from TB Copyright: © 2015 Wubuli et al. This is an open surveillance system database. Population data were extracted from Xinjiang Statistical access article distributed under the terms of the Yearbook (2006~2014). -

Discrimination, Mistreatment and Coercion

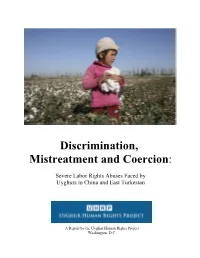

Discrimination, Mistreatment and Coercion: Severe Labor Rights Abuses Faced by Uyghurs in China and East Turkestan A Report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project Washington, D.C. 1 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Unemployment and Income Inequality in East Turkestan 6 3. Hiring Discrimination Against Uyghurs 13 4. Uyghur Experiences of Labor Rights Abuses 29 5. Rural Uyghurs’ Labor Rights and Labor Transfers 39 6. China’s Labor Law and Policies 50 7. Recommendations 54 8. Appendix 56 9. Acknowledgements 59 Image credit: Chung, Chien-Min. October 19, 2005 A young girl helps her family pick cotton on in Makit County, Kashgar Prefecture. © Getty Images 2 1. Executive Summary Unemployment is one of the biggest challenges facing the Uyghur people in East Turkestan. The primary driver of Uyghur unemployment is ethnic discrimination. This report analyzes the sources and manifestations of ethnic discrimination and other labor rights abuses affecting Uyghurs in East Turkestan and elsewhere in China. In addition to structural disadvantages obtaining and retaining non-agricultural work, the vast majority of Uyghurs who work in agriculture face a unique set of violations to their labor rights. Finally, those in the Chinese government’s labor transfer program, redistributing the so-called rural labor surplus to inner Chinese cities to work in factory jobs, also face a host of labor rights challenges. Chinese law and international obligations notwithstanding, the Chinese government is at best complicit and at worst itself a major agent of labor rights abuses against Uyghurs. The Uyghur economist Ilham Tohti identified unemployment as one of the greatest obstacles between healthy relations between Uyghurs and Han Chinese in East Turkestan.