The Irish Céilí: a Site for Constructing, Experiencing, and Negotiating a Sense of Community and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tradition and Innovation in Irish Instrumental Folk Music

TRADITION AND INNOVATION IN IRISH INSTRUMENTAL FOLK MUSIC by ANDREW NEIL fflLLHOUSE B.Mus., The University of British Columbia, 1990 B.Ed., The University of British Columbia, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2005 © Andrew Neil Hillhouse, 2005 11 ABSTRACT In the late twentieth century, many new melodies were composed in the genre of traditional Irish instrumental music. In the oral tradition of this music, these new tunes go through a selection process, ultimately decided on by a large, transnational, and loosely connected community of musicians, before entering the common-practice repertoire. This thesis examines a representative group of tunes that are being accepted into the common- practice repertoire, and through analysis of motivic structure, harmony, mode and other elements, identifies the shifting boundaries of traditional music. Through an identification of these boundaries, observations can be made on the changing tastes of the people playing Irish music today. Chapter One both establishes the historical and contemporary context for the study of Irish traditional music, and reviews literature on the melodic analysis of Irish traditional music, particularly regarding the concept of "tune-families". Chapter Two offers an analysis of traditional tunes in the common-practice repertoire, in order to establish an analytical means for identifying traditional tune structure. Chapter Three is an analysis of five tunes that have entered the common-practice repertoire since 1980. This analysis utilizes the techniques introduced in Chapter Two, and discusses the idea of the melodic "hook", the memorable element that is necessary for a tune to become popular. -

How Perception, Power, and Practice Altered Memory of Irish Ceili Dances

Vol. 11(1), pp. 1-9, January-June 2021 DOI: 10.5897/JMD2020.0082 Article Number: C8FA78A66197 ISSN 2360-8579 Copyright © 2021 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Journal of Music and Dance http://www.academicjournals.org/JMD Full Length Research Paper Examining “The book”: How perception, power, and practice altered memory of Irish Ceili dances Helen Buck-Pavlick Independent Researcher, Phoenix, Arizona, USA. Received 29 May, 2020; Accepted 9 February, 2021 This paper is an ethnographic examination and exploration of the power politics of the Ar Rinci Foirne and the subsequent changes in perceived nationalism, stylizations, and memory of Irish dance as it refers to both the practiced repertoire and textual archive of ceili dancing within Ireland and the Diaspora. The researcher examined each iteration of the Ar Rinci Fiorne antecedent and relevant texts the socio-political climate following the Irish Civil War, and the aims of the Gaelic League to determine how the textual archiving through the 2014 edition of “Ar Rinci Foirne'' affected embodied memory of Irish Ceili dancing. Theories of transculturation, ethnography, post-structuralist criticism, archiving with thematic and chronological examination of texts were utilized with a qualitative methodology. Through the intentional inclusion and exclusion of dances, the Ar Rinci Foirne functions as codification and propaganda of Irishness through dance, while systematically altering and erasing embodied memory of ceili dances within Ireland and the Diaspora. Key words: Irish dance, ceili, ethnography, embodied memory, folk dance. INTRODUCTION An Coimisiun played a significant role in the preservation the periphery by this act, and what dances or styles of Irish dance repertoire while simultaneously erasing flourished as a result? 2. -

GRIFFIN LYNCH SCHOOL of IRISH DANCING GRADE EXAMS Saturday 22Nd June 2019

GRIFFIN LYNCH SCHOOL OF IRISH DANCING GRADE EXAMS Saturday 22nd June 2019 Examiner: Theresa Kinsella Grades: Grades 1-12 Location: Epsom Methodist Church, Youth Centre Hall. 11-13 Ashley Road, Epsom, Surrey KT18 5AQ Roots Cafe: On site for light lunches, snacks and drinks Travel: Nearest Train Station: Epsom Mainline. Parking: Ashley Centre & other surrounding car parks Price: Grades 1, 2 & 3: £15 each. Grades 4, 5 & 6: £23 each. Grades 7, 8, 9 & 10: £30 each. Grades 11 & 12: £65 each. One Day only... Limited Spaces Available!! Email [email protected] to book your space before Friday 24th May 2019 GRADE EXAMS HOSTED BY GRIFFIN LYNCH We are pleased to invite you to our Grade Exams held in Epsom on Saturday 22nd June. All 12 Grade Examinations must be completed to be eligible to apply for the TCRG Examination effective from Januay 1st 2018. Dancers must produce reports from previous examinations in order to participate. Please note this is a one day exam so spaces are limited and will be allocated on a first come, first served basis on receipt of entry form complete with payment. Please see full details of exam below. DATE: Saturday 22nd June 2019 VENUE: Epsom Methodist Church, Youth Centre Hall. 11-13 Ashley Road Epsom, Surrey, KT18 5AQ TIME: Allocated time slots for each school will be given and you will be informed once all the entries for the exam have been received TRAVEL: Nearest train station is Epsom Mainline. Easy to reach from the M25 junction 9 (Leatherhead) PARKING: Ashley Centre and other surrounding car parks There is no parking at the venue, you can drop off but cannot park without a permit. -

TUNE BOOK Kingston Irish Slow Session

Kingston Irish Slow Session TUNE BOOK Sponsored by The Harp of Tara Branch of the Association of Irish Musicians, Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (CCE) 2 CCE Harp of Tara Kingston Irish Slow Session Tunebook CCE KINGSTON, HARP OF TARA KINGSTON IRISH SLOW SESSION TUNE BOOK Permissions Permission was sought for the use of all tunes from Tune books. Special thanks for kind support and permission to use their tunes, to: Andre Kuntz (Fiddler’s Companion), Anthony (Sully) Sullivan, Bonnie Dawson, Brendan Taaffe. Brid Cranitch, Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, Dave Mallinson (Mally’s Traditional Music), Fiddler Magazine, Geraldine Cotter, L. E. McCullough, Lesl Harker, Matt Cranitch, Randy Miller and Jack Perron, Patrick Ourceau, Peter Cooper, Marcel Picard and Aralt Mac Giolla Chainnigh, Ramblinghouse.org, Walton’s Music. Credits: Robert MacDiarmid (tunes & typing; responsible for mistakes) David Vrooman (layout & design, tune proofing; PDF expert and all-around trouble-shooter and fixer) This tune book has been a collaborative effort, with many contributors: Brent Schneider, Brian Flynn, Karen Kimmet (Harp Circle), Judi Longstreet, Mary Kennedy, and Paul McAllister (proofing tunes, modes and chords) Eithne Dunbar (Brockville Irish Society), Michael Murphy, proofing Irish Language names) Denise Bowes (cover artwork), Alan MacDiarmid (Cover Design) Chris Matheson, Danny Doyle, Meghan Balow, Paul Gillespie, Sheila Menard, Ted Chew, and all of the past and present musicians of the Kingston Irish Slow Session. Publishing History Tunebook Revision 1.0, October 2013. Despite much proofing, possible typos and errors in melody lines, modes etc. Chords are suggested only, and cannot be taken as good until tried and tested. Revision 0.1 Proofing Rough Draft, June, 2010 / Revision 0.2, February 2012 / Revision 0.3 Final Draft, December 2012 Please report errors of any type to [email protected]. -

Consolidated Word List Words Appearing Infrequently

The Spelling Champ Consolidated Word List: Words Appearing Infrequently TheSpellingChamp.com Website by Cole Shafer-Ray TheSpellingChamp.com abacist abrader abuzz aback abrash academese abash abridge acalculia abatable abridged acanthosis abate abrotine accelerometer abatement abruption acceptant n abscise accessibility L > F the act or process of reducing in absent accessioned degree or intensity. adj The city council passed a law accessit allowing periodic bans on the L > F > E burning of wood, paving the way not existing in a place. accessorized for further pollution abatement. Zebra mussels were at one time totally absent from the Great accessory abbey Lakes. accidence abdication absentee accident abduct absolution n acclimate abeam L acclimatize abhorrently a rite, ceremony, or form of words in which a remission of sins is accommodating abient pronounced, proclaimed, or adj prayerfully implored by a priest or abigail minister. L + Ecf Father O’Malley performed the rite disposed to be helpful or obliging. abiogenic of absolution on behalf of the thief The accommodating chef prepared adj who had just made his confession. the dish exactly as the diner asked. Gk + Gk + Gk absonant accommodations not produced by the action of living organisms. absorb accomplished Randy explained to the group that rock formations are completely abstinent accomplishment abiogenic. abstractum accountable abjure n accountancy abode L an entity considered apart from any accounting abolitionary particular object or specific instance. accouplement aboriginally Virtue is an abstractum. accrete aborigines abusage accumulation aboveboard abusing accustom abradant abut Page 1 of 153 TheSpellingChamp.com 2004 Scripps National Spelling Bee Consolidated Word List: Words Appearing Infrequently ace acromegaly adhesion v n n L > F > E Gk + Gk L make (a hole in golf) in one stroke. -

50Ú Oireachtas Rince Na Cruinne 2021 the 50Th World Irish Dancing

An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha 50ú Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne 2021 The 50th World Irish Dancing Championships 2021 Dublin Convention Centre, Spencer Dock North Wall, Dublin D01 T1W6, Ireland Sunday, 28th March - Sunday 4th April, 2021 Contents Page 1 Venue and Dates Page 2 Contents and Information on Covid 19 Restrictions Page 3 50ú Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne 2021 Page 4 New for 2021 Page 5 Rules and Directives for Solo Dancing Page 6 World Solo Dancing Championships – Men/Boys Page 7 World Solo Dancing Championships – Ladies/Girls Page 8 Set Dances permitted Page 9 Age Concessions in Team Dancing Page 10 Rules & Directives for Céilí Dancing Page 12 World Céilí Dancing Championships Page 13 Rules & Directives for Figure Dancing Page 14 Figure Dancing - Musical Accompaniment & Ownership of Music Page 15 World Figure Dancing Championships Page 16 Rules and Directives for Dance Drama Page 17 World Dance Drama Championship Page 18 General Rules for Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne 2021 Page 23 Fees and closing dates Page 24 CLRG Media Policy and Information from the Marketing Committee Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne – Covid 19 Restrictions An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha reserves the right to amend this syllabus to facilitate Covid19 restrictions. It is only by working together with a flexible, understanding and co-operative outlook, that this event can take place. At the time of the syllabus being released it is anticipated that there is a high possibility of some sort of social distancing requirement still being in place during the course of the Oireachtas. This could result in a maximum number of attendees being admitted into competition arenas at any one time and determine a finite number of people allowed to accompany any one competitor. -

Oireachtas Info

TEELIN SCHOOL OF IRISH DANCE EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT AN OIREACHTAS (…WELL OK, ALMOST EVERYTHING…) WHAT IS AN OIREACHTAS? Within the context of Irish dance, Oireachtas (pronounced “O-ROCK-TUS”) is an annual regional championship competition. Prestigious in its own right, the Oireachtas also serves as a qualifying event for the National and World Competitions. The Teelin School of Irish Dance is part of the Southern Region, one of the seven regions in North America. The Southern Region Oireachtas is also referred to as “the SRO”. The Irish word "oireachtas" literally means "gathering". A convenient mnemonic for the spelling of Oireachtas is “Oh, I reach to a star”. (Note: Outside of Irish dancing context, the term “Oireachtas” is the national parliament or legislature of the Republic of Ireland.) WHAT ARE THE COMPETITIONS AT OIREACHTAS? There are two broad categories of competitions at Oireachtas: solos and teams. Solo championships at Oireachtas are qualifying events for the World Championships. Registration is open only to TCRG’s (certified teachers), who are ultimately responsible for registering the competitors they feel will positively reflect their school. Solo championships are divided by age and gender only, not by levels. Each competitor performs a hard shoe dance (treble jig or hornpipe) and a soft shoe dance (reel or slip jig) specified by the Oireachtas syllabus. The cumulative scores from those two rounds determine which dancers will be recalled to perform a hard shoe set dance in the third round. Dancers who advance to the third round are awarded placements, and the top percentage of dancers within eligible age groups qualify for the World Championships. -

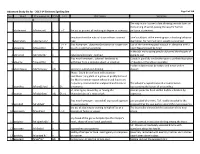

2013-14 Emirates Spelling Bee No. Word Pronunciation POS Definition

Advanced Study list for - 2013-14 Emirates Spelling Bee Page 1 of 109 No. Word Pronunciation POS LOO Definition Sentence A The city council passed a law allowing periodic bans on the burning of wood, paving the way for further 1 abatement /ә'bātmәnt/ n L > F the act or process of reducing in degree or intensity. pollution abatement. deviation from the natural state or from a normal Jane’s outburst at the meeting was a shocking behavior 2 aberration /,abә'rāshәn/ n L type. aberration, for her manner is usually so reserved. L > F + [has homonym: obeyance] cessation or suspension Use of the swimming pool was put in abeyance until a 3 abeyance /ә'bāәn(t)s/ n Ecf (as of a customary practice). new lifeguard could be hired. In the 60s many young people abhorred the thought of 4 abhorred /әb'hŏ(ә)rd/ v L detested extremely : loathed. going to war. [has near homonym: adience] tendency to Claudia’s painfully shy brother gave a perfect illustration 5 abience /'abēәn(t)s/ n L withdraw from a stimulus object or situation. of abience at the school assembly. Evelyn is abstemious by nature and never orders 6 abstemious /abz'tēmēәs/ adj L sparing in eating and drinking. dessert. [Note: Could be confused with adjective acanthous.] any plant of a genus of prickly herbs of the Mediterranean region whose broad leaves are frequently represented in sculptured architectural The column’s capital featured ornamentation 7 acanthus /ә'kan(t)thәs/ n Gk ornaments. representing the leaves of an acanthus. of, relating to, caused by, or having the Acarian parasites have saclike bodies unbroken by 8 acarian /ә'ka(a)rēәn/ adj Gk > L characteristics of a mite or tick. -

The Mcclanahan School Parents Association Proudly Presents The

The McClanahan School REGISTRATION INFORMATION Parents Association Online registration opens from to June 10 proudly presents the: www.QuickFeis.com After June 10 all registration must be done in person at the Feis 400 Grades – 250 Champs (PC & OC) Online payment with credit cards only At the Feis payment with credit cards or cash only Day of feis registrations and changes will be accepted HOTEL INFORMATION • The Louisville Feis has reserved a block of rooms LOUISVILLE FEIS rooms at the: Marriott Louisville East 1903 Embassy Square Blvd Saturday – June 20, 2020 Louisville, KY 40299 • $139 (rate good until 5/10/20) MID AMERICA SPORTS • Booking link: 1906 Watterson Trail https://book.passkey.com/e/50035087 Louisville, KY 40299 NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS 2020 NAFC Belt Championships Will be at the 2020 Lavin-Cassidy Feis Grand Geneva Resort and Spa 7036 Grand Geneva Way Lake Geneva, WI, USA 53147 Feis ........ Fri & Sat – Feb 28-29,2020 Ceili ........ Saturday February 29, 2020 Belt ........ Sun March 1, 2020 Edward Callaghan Music Scholarship Championship Under 15 - will be held at the East Durham Feis on August 22, 2020 James Brennan Music Scholarship Championship Under 21 - will be held at the Buffalo Feis on June 6, 2020 LOUISVILLE FEIS INFORMATION NAFC COMMISSION https://www.mcclanahanirish Member of the North American Feis Commission President: Jim Graven dance.com/louisvillefeis [email protected] Member of An Coimisiun, Dublin, Ireland LOUISVILLE FEIS FEIS FEES REGISTRATION RULES US Funds ONLY – Payment due at time of registration • Payment must be made at the time of registration Online registration will accept credit card payment only • In Person registration will accept credit card or cash No personal checks will be accepted • Sorry - no checks will be accepted at any time There is NO waiting list • Entries are not valid until full payment is received. -

Sunday April 7, 2019

NAFC COMMISSION Member of the North American Feis Commission President: Jim Graven [email protected] Member of An Coimisiun, Dublin, Ireland NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS Edward Callaghan Music Scholarship Championship Under 15 - will be held at the Golden Horseshoe Feis on June 15, 2019 James Brennan Music Scholarship Championship Under 21 - will be held at the FEIS INFORMATION Peach State Feis on May 4, 2019 NAFC Championship Belts Sunday Sacramento, CA - January 19th, 2019 Gerry Campbell Senior Belt Robert Gabor Junior Belt April 7, 2019 George Sweetnam Minor Belt Hyatt Regency Dulles 2300 Dulles Corner Blvd. Herndon, VA FEIS REGISTRATION SUMMARY (right next to Dulles Airport!) Up to March 27, all registration only accepted at www.quickfeis.com Feis caps are: (registration will close for those levels only once that cap has been reached) o Grades..................... 650 o Championship ......... 350 All results will be printed and given out for FREE at the feis for both championship and grades levels All results will also be available for FREE on your QuickFeis account during and after the feis Competitions will be combined and split to ensure that as many competitions will have 5 or Feis start time is at 8:00 am more dancers Syllabus approved on 05 Jan 2019 McGrath Feis COMPETITION FEES MCGRATH FEIS RULES NUMBER OF COMPETITORS: The Feis Committee Competition Fees FEES reserves the right to combine or split competitions. Solo Dancing / Charity TR / Sets / All grades up to and including U14 will dance three $ 10 Specials (per competitor and per dance) at a time. All champs up to and including U14 will dance hard Preliminary Championship $ 40 shoe three at a time and soft shoe two at a time. -

Irish-Dances-Emma.Pdf

Irish Dances Introduction My topic is going to be the Irish traditional dances. I’ve decided to do this work about these type of dances because my great grandmother’s family was Irish, and i just wanted to know a bit more about my roots, specially the dance there in Ireland, because i think it’s one of the most beautifully curious local traditions and cultures. History When the Celts arrived in Ireland from central Europe over two thousand years ago, they brought with them their own folk dances. There is evidence that among its first practitioners were the Druids, who danced in religious rituals honoring the oak tree and the sun. Types v Irish Céilí Dances v Irish Step Dancing v Irish Céilí Dances A céilí is a social gathering featuring Irish music and dance. Céilí dancing is a specific type of Irish dance. Some céilithe (plural of céilí) will only have céilí dancing, some only have set dancing, and some will have a mixture. Irish social, or céilí dances vary widely throughout Ireland and the rest of the world. A céilí dance may be performed with as few as two people and as many as sixteen. Céilí dances may also be danced with an unlimited number of couples in a long line or proceeding around in a circle. Céilí dances are often fast and some are quite complex. The céilí dances are typically danced to Irish instruments such as the Irish bodhrán or fiddle in addition to the concertina (and similar instruments), guitar, whistle or flute. v Irish Step Dancing Stepdancing as a modern form is descended directly from old-style step dancing. -

Rialacha Fleadhanna Ceoil 2017 As Amended by CCÉ Congress 2016

Rialacha Fleadhanna Ceoil 2017 As amended by CCÉ Congress 2016 English INDEX Section Page General Rules and Entry Procedure 2 Official Fleadh Cheoil Competitions 6 Performance Requirements: Competitions 1-39 8 Competitions 40-43: Rince Céilí/Céilí Dancing 12 Competitions 44-47: Rince Seit/Set Dancing 14 Competition 48: Rince ar an Sean-Nós 16 Competition 49: Comhrá Gaeilge 17 Fleadhanna Ceoil: Structures and General Procedures 18 Competition Procedure 19 Adjudication Procedure 20 Clerks and Stewards 22 Prizes 23 Fleadh Committee and Administrative Procedure 24 County and Regional Fleadhanna 26 Provincial Fleadhanna 27 Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann 29 GENERAL RULES AND ENTRY PROCEDURE 1. Mission Statement: Fleadhanna Ceoil shall be held to propagate, consolidate and perpetuate our Irish traditional music, both vocal and instrumental, dance as well as An Teanga Gaeilge, by presenting it in a manner worthy of its dignity, and in accordance with the Aims and Objectives of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann. It is not intended that competitions should be merely a means by which a competitor may gain a prize or defeat a rival, but rather a medium in which ‘these competitors may pace each other on the road to excellence’. 2. All competitions shall be traditional in character and in conformity with the Bunreacht of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann. 3. Rialacha Fleadhanna Ceoil and Clár na gComórtas provide for all CCÉ Fleadh Competitions listed 1-51. The procedures, guidelines and rules outlined in Rialacha Fleadhanna Ceoil and Clár na gComórtas apply to all