Stand-Up Comedy and Social Justice: a Discussion of Freedom of Speech and Inclusive Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculated for the Use of the State Of

3i'R 317.3M31 H41 A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of IVIassachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1839amer MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER, AND mmwo states ©alrntiar, 1839. ALSO CITY OFFICERS IN BOSTON, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY JAMES LORING, 13 2 Washington Street. ECLIPSES IN 1839. 1. The first will be a great and total eclipse, on Friday March 15th, at 9h. 28m. morning, but by reason of the moon's south latitude, her shadow will not touch any part of North America. The course of the general eclipse will be from southwest to north- east, from the Pacific Ocean a little west of Chili to the Arabian Gulf and southeastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The termination of this grand and sublime phenomenon will probably be witnessed from the summit of some of those stupendous monuments of ancient industry and folly, the vast and lofty pyramids on the banks of the Nile in lower Egypt. The principal cities and places that will be to- tally shadowed in this eclipse, are Valparaiso, Mendoza, Cordova, Assumption, St. Salvador and Pernambuco, in South America, and Sierra Leone, Teemboo, Tombucto and Fezzan, in Africa. At each of these places the duration of total darkness will be from one to six minutes, and several of the planets and fixed stars will probably be visible. 2. The other will also be a grand and beautiful eclipse, on Satur- day, September 7th, at 5h. 35m. evening, but on account of the Mnon's low latitude, and happening so late in the afternoon, no part of it will be visible in North America. -

The Great Apostasy

The Great Apostasy R. J. M. I. By The Precious Blood of Jesus Christ; The Grace of the God of the Holy Catholic Church; The Mediation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Good Counsel and Crusher of Heretics; The Protection of Saint Joseph, Patriarch of the Holy Family and Patron of the Holy Catholic Church; The Guidance of the Good Saint Anne, Mother of Mary and Grandmother of God; The Intercession of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael; The Intercession of All the Other Angels and Saints; and the Cooperation of Richard Joseph Michael Ibranyi To Jesus through Mary Júdica me, Deus, et discérne causam meam de gente non sancta: ab hómine iníquo, et dolóso érue me Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam 2 “I saw under the sun in the place of judgment wickedness, and in the place of justice iniquity.” (Ecclesiastes 3:16) “Woe to you, apostate children, saith the Lord, that you would take counsel, and not of me: and would begin a web, and not by my spirit, that you might add sin upon sin… Cry, cease not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and shew my people their wicked doings and the house of Jacob their sins… How is the faithful city, that was full of judgment, become a harlot?” (Isaias 30:1; 58:1; 1:21) “Therefore thus saith the Lord: Ask among the nations: Who hath heard such horrible things, as the virgin of Israel hath done to excess? My people have forgotten me, sacrificing in vain and stumbling in their way in ancient paths.” (Jeremias 18:13, 15) “And the word of the Lord came to me, saying: Son of man, say to her: Thou art a land that is unclean, and not rained upon in the day of wrath. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Volume 7, No. 4, Winter 1996 General Announcements

Volume 7, No. 4, Winter 1996 General Announcements The Man and Nature Research Center, located at Odense University, Denmark, ends its five-year life in June 1997. The Center has been prominent on the European scene in environmental ethics and policy issues, producing some 100 working papers and many dozens of conferences and seminars in the field, hosting also many scholars from Europe and abroad. Many of these working papers remain available, as are some video productions. Information on the website is at http://www.hum.ou.dk/Center/Hollufgaard/index.html. A philosopher involved with the project is Finn Arler. Mailing address: Man and Nature: Humanities Research Center, Hollufgaard, Hestehaven 201, 5220 Odense SO, Denmark. Phone 45 6595 9493. Fax 45 6595 7766. The Syllabus Project, the most comprehensive and up-to-date source of information concerning course offerings in environmental philosophy and environmental ethics, is being supported by the International Society for Environmental Ethics, the Center for Environmental Philosophy, the Philosophy Documentation Center, and the Philosophy Department at Bowling Green State University. The materials can be accessed on the World Wide Web at: http://www.bgsu.edu/departments/phil/ISEE The project's goal is to collect information from throughout the world about what courses are taught, by whom, in which colleges and universities, and to make this available on website for teachers, administrators, students, prospective grad students, and so on. All teachers of such courses are requested to send copies of their syllabuses, course materials, Resumé, etc., preferrably by Email (disks should be text/ASCII only). As a last resort, send a paper-mail copy. -

THTR 474 Intro to Standup Comedy Spring 2021—Fridays (63172)—10Am to 12:50Pm Location: ONLINE Units: 2

THTR 474 Intro to Standup Comedy Spring 2021—Fridays (63172)—10am to 12:50pm Location: ONLINE Units: 2 Instructor: Judith Shelton OfficE: Online via Zoom OfficE Hours: By appointment, Wednesdays - Fridays only Contact Info: You may contact me Tuesday - Friday, 9am-5pm Slack preferred or email [email protected] I teach all day Friday and will not respond until Tuesday On Fridays, in an emergency only, text 626.390.3678 Course Description and Overview This course will offer a specific look at the art of Standup Comedy and serve as a laboratory for creating original standup material: jokes, bits, chunks, sets, while discovering your truth and your voice. Students will practice bringing themselves to the stage with complete abandon and unashamed commitment to their own, unique sense of humor. We will explore the “rules” that facilitate a healthy standup dynamic and delight in the human connection through comedy. Students will draw on anything and everything to prepare and perform a three to four minute set in front of a worldwide Zoom audience. Learning Objectives By the end of this course, students will be able to: • Implement the comic’s tools: notebook, mic, stand, “the light”, and recording device • List the elements of a joke and numerous joke styles • Execute the stages of standup: write, “get up”, record, evaluate, re-write, get back up • Identify style, structure, point of view, and persona in the work we admire • Demonstrate their own point of view and comedy persona (or character) • Differentiate audience feedback (including heckling) -

Globalization and the Common Humanity: Ethical and Institutional Concerns

Globalization. Ethical and Institutional Concerns Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, Acta 7, Vatican City 2001 www.pass.va/content/dam/scienzesociali/pdf/acta7/acta7-ramirez2.pdf GLOBALIZATION AND THE COMMON HUMANITY: ETHICAL AND INSTITUTIONAL CONCERNS MINA M. RAMIREZ This Report tries to present a synthesis (without entering into the tech- nical aspects) of the phenomenon of globalization, underscoring the nega- tive and the positive aspects as well as the Challenges of Globalization gleaned from the topical discussions of this assembly with special reference to the most affected – the monetarily poor of the world. The Approach to Globalization The objective of the assembly is to highlight the findings of Social Science with regard to Globalization offering these to the Catholic Church for the development of her Christian Social Teachings (President E. Malinvaud). The approach should be balanced, avoiding two extreme attitudes: 1) to resist globalization without understanding its nuances, and/or 2) to subtly reduce it to one of its many aspects. As an Academy, the PASS wishes to contribute to the Church the positive and negative implications for devel- oping countries of Globalization through the analysis and critique of its underlying values and ethics. PASS at this stage is not looking for unanim- ity. It is rather challenging one’s certainty and bringing out ideas in its plu- rality. (Prof. L. Sabourin). A great task, it nevertheless is watching for con- verging points. Rev. Fr. Prof. Johannes Schasching, S.J. brought to light the historical evolution of Christian Social Teachings (CSTs), the Church’s actual point of view and latest development in relation to her all inclusive nature, address- ing herself not only to the hierarchy of the Church, but also to other church- es, all religions and all women and men of goodwill. -

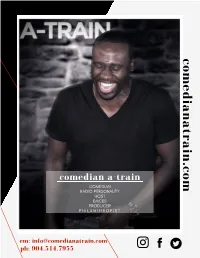

Comedian A-Train M COMEDIAN RADIO PERSONALITY HOST EMCEE PRODUCER P H I L a N T H R O P I S T

c o m e d i a n a t r a i n . c o comedian a-train m COMEDIAN RADIO PERSONALITY HOST EMCEE PRODUCER P H I L A N T H R O P I S T em: [email protected] ph: 904.514.7955 COMEDIAN A-TRAIN as seen and heard on bio Comedian A-Train, seen on WEtv’s Braxton Family Values, The Low Down with James Yon, River City Live, First Coast Living, and The Chat, is host of Yo Daddy’ Nem Podcast—iHeart Radio’s #1 Podcast in Duval, former co-host of Jacksonville’s #1 morning show, on 107.9 and Jacksonville’s #1 drive-time radio show on 103.7. He's a clean, traveling, stand-up, and corporate comedian, host and emcee. He tours with Original King of Comedy D. L. Hughley, and has toured with Kountry Wayne. He has featured for the biggest names in clean comedy, Michael Jr., viral sensation KevonStage, Dave Coulier (Uncle Joey on Full House), and Preacher Lawson (AGT). He's performed with Pete Lee (Jimmy Fallon and VH1’s Best Week Ever), Comedienne Dominique (Last Comic Standing), Bill Bellamy (Who's Got Jokes and Ladies Night Out), Ali Siddiq (Bring the Funny and Comedy Central), Loni Love (The Real), Deon Cole (Blackish and Grownish), Ronnie Jordan (Bossip), Huggy Low Down and Chris Paul (Tom Joyner Morning Show), and many others. Comedian A-Train has hosted the Zora Neal Hurston Festival, Orlando Jazz Festival, Steel City Jazz Festival— Birmingham, and Jacksonville Jazz Festival—the second largest in the country where he’s the first and only comedian to host in the city’s 40-year history. -

Festival Program Canberracomedyfestival.Com.Au

Over 50 Hilarious Shows! Festival Program canberracomedyfestival.com.au canberracomedyfestival canberracomedy canberracomedy #CBRcomedy Canberra Comedy Festival app ► available for iPhone & Android DINE LAUGH STAY FIRST EDITION BAR & DINING CANBERRA COMEDY FESTIVAL NOVOTEL CANBERRA Accommodation from $180* per room, per night Start the night off right with a 3 cheese platter & 2 house drinks for only $35* firsteditioncanberra.com.au 02 6245 5000 | 65 Northbourne Avenue, Canberra novotelcanberra.com.au *Valid 19 - 25 March 2018. House drinks include house beer, house red and white wine only. Accommodation subject to availability. T&C’s apply. WELCOME FROM THE CHIEF MINISTER I am delighted to welcome you to the Canberra Comedy Festival 2018. The Festival is now highly anticipated every March by thousands of Canberrans as our city transforms into a thriving comedy hub. The ACT Government is proud to support the growth of the Festival year-on- year, and I’m pleased to see that 2018 is the biggest program ever. In particular, in 2018, that growth includes the Festival Square bar and entertainment area in Civic Square. The Festival has proven Canberra audiences are on the cutting edge of arts participation. Shows at the Festival in 2017 went on to be nominated for prestigious awards around the country, and one (Hannah Gadsby) even picked up an impressive award at the 2017 Edinburgh Fringe Festival. I’ve got tickets for a few big nights at the Festival, and I hope to see you there. Andrew Barr MLA ACT Chief Minister CANBERRA COMEDY FESTIVAL GALA Tue 20 March 7pm (120min) $89 / $79 * Canberra Theatre, Canberra Theatre Centre SOLD OUT. -

'Undateable' Guys Go on Tour

'Undateable' Guys Go on Tour 02.25.2014 "Undateable" is a new comedy coming to NBC about a group of friends going through a rut. In order to promote these guys and their stories leading up to the show's debut, NBC and Warner Bros. figured they'd first introduce them to everyone in person. So throughout March, four of the stars of the show (who also happen to be standup comedians) will join executive producer Bill Lawrence on a multi-city standup comedy tour, spanning the U.S. Lawrence, who will serve as host, and stars Chris D'Elia, Ron Funches, Brent Morin and Rick Glassman will start in New York on March 2 and head across the country, ending the tour in Los Angeles on March 20 (full schedule below). "Since it's so hard to launch a network comedy in this competitive landscape, we thought we would try a little grassroots marketing," said "Undateable" co-creator and executive producer Adam Sztykiel. "Plus, it will be exciting to see Bill travel around in a van." The series, based on the book "Undateable: 311 Things Guys Do That Guarantee They Won't Be Dating or Having Sex," will premiere later this year on NBC. For a taste of what to come, check out some of D'Elia's standup below: Chris D'Elia: White Male. Black Comic. Get More: Watch More Stand-Up. Schedule: 3/2/2014 New York, NY; Carolines On Broadway 3/3/2014 Boston, MA; Laugh Boston at The Westin Boston 3/4/2014 Philadelphia, PA; Underground Arts 3/5/2014 Washington, D.C.; DC Improv 3/11/2014 Dallas, TX; Addison Improv 3/12/2014 Houston, TX; Houston Improv 3/17/2014 Chicago, IL; Up Comedy Club 3/18/2014 Detroit, MI; The Magic Bag 3/20/2014 Los Angeles, CA (venue TBD) [Image courtesy of NBC]. -

The Capability Approach As Political Philosophy

New Directions for the Capability Approach: Deliberative Democracy and Republicanism Rutger Claassen Published in: Res Publica 15(4)(2009): 421-428 Review essay on: John. M. Alexander, Capabilities and Social Justice: The Political Philosophy of Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008, 187 pp David A. Crocker, Ethics of Global development. Agency, Capability, and Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, 416 pp. The capability approach, developed by economist Amartya Sen and philosopher Martha Nussbaum in the 1980s and 1990s, has had an impact on two main fields of study. First it has brought a distinctive set of tools and ideas to research on human development, well-being and quality of life. David Crocker’s Ethics of Global Development presents itself as a contribution to this field. More specifically, Crocker proposes his version of capability theory as a guide to the emerging discipline of ‘international development ethics’. A second field in which the capability approach has figured extensively is that of theories of justice in political philosophy. Both Sen and Nussbaum have stressed that the capability approach is not a full theory of justice yet. More work needs to be done to make ‘equality of capabilities’ a conception of justice competing with theories of justice like those of John Rawls, Robert Nozick and Ronald Dworkin. John Alexander’s Capabilities and Social Justice aims to be a philosophical evaluation of the capability approach’s contribution in this field. Both books are heavily indebted to Sen and Nussbaum and extensively discuss their arguments. Readers interested in Sen and Nussbaum’s work on capabilities will therefore find much of interest in both books. -

The One and Only Ivan” Is an Unforgettable Tale About the Beauty of Friendship, the Power of a Visualization and the Significance of the Place One Calls Home

“You cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around you. What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.” ― Dr. Jane Goodall n adaptation of the award-winning book about one very special gorilla, Disney’s “The One and Only Ivan” is an unforgettable tale about the beauty of friendship, the power of A visualization and the significance of the place one calls home. The story follows Ivan, a 400-pound silverback gorilla, who shares a communal habitat in a suburban shopping mall with Stella the elephant, Bob the dog, and various other animals. Ivan has few memories of the jungle where he was born, but when a baby elephant named Ruby arrives, it touches something deep within him. Ivan begins to question his life, where he comes from and where he ultimately wants to be. The heartwarming adventure, which comes to the screen in an impressive hybrid of live-action and CGI, is based on Katherine Applegate’s bestselling book, which won numerous awards upon its publication in 2013, including the Newbery Medal. The movie stars: Sam Rockwell as the voice of Ivan; Angelina Jolie as the voice of Stella; Danny DeVito as the voice of Bob the dog; Helen Mirren as the voice of Snickers the poodle; Brooklynn Prince as the voice of Ruby; Ramon Rodriguez as the mall employee George; Ariana Greenblatt as George’s daughter Julia; Chaka Khan as the voice of Henrietta the chicken; Mike White as the voice of Frankie the seal; Ron Funches as the voice of Murphy the rabbit; Phillipa Soo as the voice of Thelma the macaw; and Bryan Cranston as Mack, the circus attraction’s owner. -

Polysèmes, 23 | 2020 Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” 2

Polysèmes Revue d’études intertextuelles et intermédiales 23 | 2020 Contemporary Victoriana - Women and Parody Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” Quand la parodie rencontre la satire : “Lady Addle“ dépasse les limites Margaret D. Stetz Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/polysemes/7691 DOI: 10.4000/polysemes.7691 ISSN: 2496-4212 Publisher SAIT Electronic reference Margaret D. Stetz, « Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” », Polysèmes [Online], 23 | 2020, Online since 30 June 2020, connection on 02 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/polysemes/7691 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/polysemes.7691 This text was automatically generated on 2 July 2020. Polysèmes Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” 1 Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” Quand la parodie rencontre la satire : “Lady Addle“ dépasse les limites Margaret D. Stetz 1 For scholars of humour, there is a certain fascination in studying parodies that are now little known, especially if once they were well known. Why, we want to ask, were they popular in an earlier time? To whom did they appeal and why? What might these works say to us today? In the case of a series of four works of fiction produced by Mary Dunn (1900-1958), a British writer for the satirical magazine Punch, a second set of questions arises. These same four volumes, each one purporting to be written by a fictional British aristocrat named “Lady Addle”, were published from the mid-1930s through the late 1940s, but were reprinted in the 1980s and enjoyed both a second wave of sales in British bookshops and enthusiastic reviews in British periodicals.