Making Safer Streets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Departmentof Parks

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENTOF PARKS BOROUGH OF THE BRONX CITY OF NEW YORK JOSEPH P. HENNESSY, Commissioner HERALD SQUARE PRESS NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH OF 'I'HE BRONX January 30, 1922. Hon. John F. Hylan, Mayor, City of New York. Sir : I submit herewith annual report of the Department of Parks, Borough of The Bronx, for 1921. Respect fully, ANNUAL REPORT-1921 In submitting to your Honor the report of the operations of this depart- ment for 1921, the last year of the first term of your administration, it will . not be out of place to review or refer briefly to some of the most important things accomplished by this department, or that this department was asso- ciated with during the past 4 years. The very first problem presented involved matters connected with the appropriation for temporary use to the Navy Department of 225 acres in Pelham Bay Park for a Naval Station for war purposes, in addition to the 235 acres for which a permit was given late in 1917. A total of 481 one- story buildings of various kinds were erected during 1918, equipped with heating and lighting systems. This camp contained at one time as many as 20,000 men, who came and went constantly. AH roads leading to the camp were park roads and in view of the heavy trucking had to be constantly under inspection and repair. The Navy De- partment took over the pedestrian walk from City Island Bridge to City Island Road, but constructed another cement walk 12 feet wide and 5,500 feet long, at the request of this department, at an expenditure of $20,000. -

"Judicial Corruption"

16/06/2017 Gmail - "JUDICIAL CORRUPTION" William Finnerty <[email protected]> "JUDICIAL CORRUPTION" William Finnerty <[email protected]> Fri, Jun 16, 2017 at 3:10 PM To: "First Minister of Northern Ireland Arlene Foster LL.B. MLA" <[email protected]>, [email protected], "Northern Ireland Justice Department, Case Ref: COR/1248/2016" <private.office@justice- ni.x.gsi.gov.uk>, Northern Ireland Justice Minister Claire Sugden MLA <[email protected]>, Northern Ireland Minister For Finance Máirtín Ó Muilleoir MLA <[email protected]>, Northern Ireland Minister for Health Michelle O'Neill MLA <[email protected]>, [email protected], "Lawyer Paul J. O'Kane LL.B." <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Aoife McShane LL.B." <[email protected]>, Lawyer Rory McShane <[email protected]>, Lawyer Mary Doherty <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Ronan McGuigan, LL.B. Solicitor Advocate" <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Jacqueline Malone LL.B. Solicitor Advocate" <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Louise Moley LL.B." <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Ann Marie Featherstone LL.B. LL.M." <[email protected]>, Sheila McGuigan <[email protected]>, McGuigan Malone Solicitors <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Ronan Haughey of ML White Solicitors Ltd, Newry, Northern Ireland" <[email protected]>, "John Mackell, Director of Client (Solicitor) -

Pedestrian Safety on Rural Highways

FHWA-SA-04-008 September 2004 Technical Report Pedestrian Safety on Rural Highways Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA-SA-04-008 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date (Update) Pedestrian Safety on Rural Highways September 2004 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Written By 8. Performing Organization Report No. J. W. Hall, J. D. Brogan, and M. Kondreddi 9. Performing Organization Name and Address (Update Report) 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Department of Civil Engineering, MSC01 1070 University of New Mexico 11. Contract or Grant No. Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001. 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Federal Highway Administration Office of Safety 400 Seventh Street SW Washington, DC 20590 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes AOTR: D. Smith (HSA-30); T. Redmon (HSA-20); 16. Abstract Although pedestrian fatalities have decreased by 16 percent over the past decade, the United States experienced nearly 4,749 pedestrian fatalities in 2003. The conventional wisdom has been that this is primarily an urban problem, where pedestrians are subject to numerous conflicts with vehicular traffic. The fact that 28 percent of pedestrian fatalities occur in rural areas has largely been ignored, despite the fact that pedestrian impacts in rural areas, while relatively rare, are much more likely to result in fatalities or serious injuries. The research described in this paper sought to identify the characteristics of rural pedestrian fatalities in ten states with above-average rates of rural pedestrian fatalities. The most prominent characteristics of rural pedestrian fatalities in these states were clear weather, hours of darkness, weekends, non- intersection locations, and level, straight roads. -

Highway Safety Act of 1973

* * PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE SAFETY STUDY Highway Safety Act of 1973 * (Section 214) Of T t ^. STATES Of a^ * MARCH 1975 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY * ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20590 * PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE SAFETY STUDY Highway Safety Act of 1973 (Section 214) MARCH 1975 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20590 CONTENTS Page SECTION I: SYNOPSIS A. Introduction .............................................. 1 B. Executive Summary ......................................... 2 C. Background .............................................. 4 D. Study Methodology ......................................... 7 E. Congressional Recommendations ................................ 12 SECTION II: PEDESTRIAN SAFETY Introduction .............................................. 13 A. Review and Evaluation of State and Local Ordinances, Regulations, and Laws Pertaining to Pedestrian Safety .................................. 14 B. Review and Evaluation of Enforcement Policies, Procedures, Methods, Practices and Capabilities for Enforcing Pedestrian Rules ................ 35 C. Relationship Between Alcohol and Pedestrian Safety ................... 36 D. Evaluation of Ways and Means of Improving Pedestrian Safety Programs ...... 43 E. Analysis of Present Funding Allocation of Pedestrian Safety Programs and an Assessment of the Capabilities of Federal, State and Local Governments to Fund Such Activities and Programs .................... 45 F. Findings ................................................59 -

Student Economic Review 2015

STUDENT ECONOMIC REVIEW 2015 UNIVERSITY OF DUBLIN TRINITY COLLEGE PRESIDENT Professor John o’h agan DePartment of economics , t rinity college Dublin PATRONS Professor PhiliP lane heaD of DePartment of economics , t rinity college Dublin Drtara mitchell DePartment of economics , t rinity college Dublin Dr ronan lyons DePartment of economics , t rinity college Dublin Dr michael Wycherley DePartment of economics , t rinity college Dublin i THE STUDENT ECONOMIC REVIEW VOL . XXIX Published by the student economic review, c/o Department of economics, trinity college, Dublin 2 republic of ireland. all rights reserved. copyright © contributors to the student economic review 2015 all views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors or sponsors. this journal claims no special rights or privileges. all correspondence or complaints should be addressed to: the editor, student economic review, c/o Department of economics, trinity college, Dublin 2, republic of ireland. Printed by brunswick Press ltd. the ser logo was created by Paul Kenny in 2003. Photography by andrew murphy, aisling crabbe and gearóid gibbs cover by séamus o’beirne the student economic review is also available online at http://www.tcd.ie/economics/ser ii SPONSORS THE STUDENT ECONOMIC REVIEW WOULD LIKE TO SINCERELY THANK ALL OF OUR SPONSORS FOR THEIR CONTINUED SUPPORT MAIN SPONSORS mr harry hartforD mrVinay nair SPONSORS mr alan gray borD na móna ms aoife cunningham iii THE STUDENT ECONOMIC REVIEW VOL . XXIX THE STUDENT ECONOMIC -

A NOVEL APPROACH for DIAGNOSING ROAD SAFETY ISSUES USING AUTOMATED COMPUTER VISION TECHNIQUES Tarek Sayed, Ph.D., P.Eng

16th Road Safety on Four Continents Conference Beijing, China 15-17 May 2013 A NOVEL APPROACH FOR DIAGNOSING ROAD SAFETY ISSUES USING AUTOMATED COMPUTER VISION TECHNIQUES Tarek Sayed, Ph.D., P.Eng. Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of British Columbia 6250 Applied Science Lane, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4 E-mail: [email protected] Mohamed H. Zaki, Ph.D. Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of Civil Engineering, University of British Columbia 6250 Applied Science Lane, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4 E-mail: [email protected] Jarvis Autey, MSc. Research Assistant, Department of Civil Engineering, University of British Columbia, 6250 Applied Science Lane, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The use of traffic conflicts for safety diagnosis has been gaining acceptance as a surrogate for collision data analysis. The traffic conflicts approach provided better understanding of collision contributing factors and the failure mechanism that leads to road collisions. This paper demonstrates an automated proactive safety diagnosis approach for vehicles, pedestrian and cyclists using video-based computer vision techniques. Traffic conflicts are automatically detected and several conflict indicators such as Time to collision (TTC) are calculated based on the analysis of the road-user positions in space and time. Additionally, spatial violations are detected based on the non-conformance of road users to travel regulations. Several case studies are described. The first case study deals of the safety analysis of a newly installed bike lane at the southern approach of a heavy volume Bridge in Vancouver, British Columbia. The results showed a high exposure of cyclists to traffic conflicts. -

ニューヨーク地下鉄路線図 Nereid Avenue Eastchester-Dyre Avenue 2018年10月13日更新 233 Street Baychester Avenue 225 Street

Wakefield-241 Street ニューヨーク地下鉄路線図 Nereid Avenue Eastchester-Dyre Avenue 2018年10月13日更新 233 Street Baychester Avenue 225 Street Van Cortlandt Park-242 Street 219 Street Pelham Bay Park Woodlawn 238 Street Gun Hill Road Gun Hill Road Buhre Avenue Mosholu Parkway Norwood 205 Street 231 Street Burke Avenue Middletown Road Bedford Park Boulevard Bedford Park Boulevard Lehman College Westchester Square- Marble Hill-225 Street Allerton Avenue Pelham Parkway East Tremont Avenue Kingsbridge Road Kingsbridge Road Pelham Parkway Morris Park Zerega Avenue Fordham Road Fordham Road 215 Street Bronx Park East Castle Hill Avenue Inwood-207 Street 183 Street 182-183 Streets 207 Street East 180 Street Parkchester Dyckman Street Burnside Avenue West Farms Square- Dyckman Street Tremont Avenue Saint Lawrence Avenue E Tremont Avenue Morrison- 190 Street 176 Street Sound View Avenues 191 Street 174-175 Streets 174 Street 181 Street Mt Eden Avenue 181 Street Elder Avenue 175 Street 170 Street 170 Street Freeman Street Whitlock Avenue 168 Street- 167 Street 167 Street Simpson Street Washington Heights 163 Street- Intervale Avenue Hunts Point Avenue Amsterdam Avenue 161 Street- Yankee Stadium 157 Street 3 Avenue-149 Prospect Avenue Longwood Avenue 155 Street 155 Street 149 Street-Grand Concourse Street Flushing-Main Street East 149 Street 145 Street 145 Street Harlem-148 145 Street Street East 143 Street - 149 Street-Grand Concourse Jackson Avenue Cypress Mets-Willets Point 137 Street-City Saint Mary's Street Avenue College 135 Street 135 Street 3 Avenue- Brook -

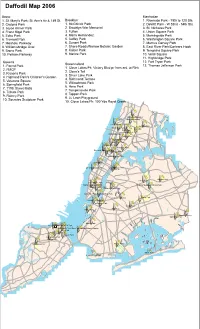

Daffodil Map 2006

Daffodil Map 2006 Bronx Manhattan 1. St. Mary's Park; St. Ann's Av & 149 St. Brooklyn 1. Riverside Park - 79th to 120 Sts. 2. Crotona Park 1. McGolrick Park 2. DeWitt Park - W 52nd - 54th Sts. 3. Joyce Kilmer Park 2. Brooklyn War Memorial 3. St. Nicholas Park 4. Franz Sigel Park 3. Fulton 4. Union Square Park 5. Echo Park 4. Maria Hernandez 5. Morningside Park 6. Tremont Park 5. Coffey Park 6. Washington Square Park 7. Mosholu Parkway 6. Sunset Park 7. Marcus Garvey Park 8. Williamsbridge Oval 7. Shore Roads/Narrow Botanic Garden 8. East River Park/Corlears Hook 9. Bronx Park 8. Kaiser Park 9. Tompkins Square Park 10. Pelham Parkway 9. Marine Park 10. Verdi Square 11. Highbridge Park Queens 12. Fort Tryon Park Staten Island 1. Forest Park 13. Thomas Jefferson Park 1. Clove Lakes Pk; Victory Blvd pr from ent. to Rink 2. FMCP 2. Clove's Tail 3. Kissena Park 3. Silver Lake Park 4. Highland Park's Children's Garden 4. Richmond Terrace 5. Veterans Square 5. Willowbrook Park 6. Springfield Park 6. Hero Park 7. 111th Street Malls 7. Tompkinsville Park 8. Tribute Park 8. Tappen Park 9. Rainey Park 9. Lt. Leah Playground 10. Socrates Sculpture Park 10. Clove Lakes Pk: 100 Yds Royal Creek Williamsbridge Oval Mosholu Parkway Fort Tryon Park Pelham Pkwy Highbridge Park Bronx Park Echo Park Tremont Park Highbridge Park Crotona Park Joyce Kilmer Park Franz Sigel Park St Nicholas Park St Mary's Park Riverside PMaorkrningside Park Marcus Garvey Park Thomas Jefferson Park Verdi Square De Witt Clinton Park Socrates Sculpture Garden Rainey Park Kissena Park 111th Street Malls Union Square Park Washington Square Park Flushing Meadows Corona Park Tompkins Square Park Monsignor Mcgolrick Park East River Park/Corlears Hook Park Maria Hernandez Park Forest Park Brooklyn War Memorial Fort Greene Park Highland Park Coffey Park Fulton Park Veterans Square Springfield Park Sunset Park Richmond TLetr.ra Nceicholaus Lia Plgd. -

HHH Collections Management Database V8.0

HENRY HUDSON PARKWAY HAER NY-334 Extending 11.2 miles from West 72nd Street to Bronx-Westchester NY-334 border New York New York County New York WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD HENRY HUDSON PARKWAY HAER No. NY-334 LOCATION: The Henry Hudson Parkway extends from West 72nd Street in New York City, New York, 11.2 miles north to the beginning of the Saw Mill River Parkway at Westchester County, New York. The parkway runs along the Hudson River and links Manhattan and Bronx counties in New York City to the Hudson River Valley. DATES OF CONSTRUCTION: 1934-37 DESIGNERS: Henry Hudson Parkway Authority under direction of Robert Moses (Emil H. Praeger, Chief Engineer; Clinton F. Loyd, Chief of Architectural Design); New York City Department of Parks (William H. Latham, Park Engineer); New York State Department of Public Works (Joseph J. Darcy, District Engineer); New York Central System (J.W. Pfau, Chief Engineer) PRESENT OWNERS: New York State Department of Transportation; New York City Department of Transportation; New York City Department of Parks and Recreation; Metropolitan Transit Authority; Amtrak; New York Port Authority PRESENT USE: The Henry Hudson Parkway is part of New York Route 9A and is a linear park and multi-modal scenic transportation corridor. Route 9A is restricted to non-commercial vehicles. Commuters use the parkway as a scenic and efficient alternative to the city’s expressways and local streets. Visitors use it as a gateway to Manhattan, while city residents use it to access the Hudson River Valley, located on either side of the Hudson River. -

Bedford Park Woodlawn Cemetery Van Cortlandt Park Norwood

Neighborhood Map ¯ Je ro m e W e t la n d W a lk Van Cortlandt Park Bainbridge Avenue Woodlawn 3700 Webster Avenue Woodlawn Cemetery Bronx Dance Academy School 19 3594 B a i n 3598 3598 b r E 213 Street id g Bx16 12 3592 e Bx24 Dekalb Avenue Bx16 A Bx24 Jerome Avenue v e n u e W4 W4 W20 W20 W21 W21 330 Decatur Avenue 3564 E 212 Street 3598 3560 3598 50 3598 3562 24 E 212 Street E 211 Street E 211 Street 220 3558 3598 E 211 Street 316 Hull Avenue 3500 Kings College Place 3598 200 3598 Rochambeau Avenue E Gun Hill Road Perry Avenue Kings College 3498 Tryon Avenue School, PS 94 3500 160 292 3598 Mosholu Wayne Avenue 344 Bainbridge Avenue 3500 323 Golf Course Sachkerah Woods 3498 Playground Bx28 3500 Bx30 E Gun Hill Road Bx38 E Gun Hill Road 304 3500 3360 245 3500 Mosholu-Pelham 215 3498 Bx28272 Greenway 3500 E Gun Hill Road Bx30 E Gun Hill Road Bx38 Place 3500 250 3500 M 3500 147 3498 o E Gun Hill Road s 11 h 3498 200 o Bx10 294 lu Reservior P 160 a E Gun Hill Road 3498 rk Place Putnam Williamsbridge Reservoir w E Gun Hill Road Keeper’s House ay Bx10 3380 10 10 3395 t 3498 es l W Mosholu Montefiore va 3498 3400 ir O 36 Community Center vo Gun Hill Meadow er es Jerome Avenue R 3400 R e 3450 Montefiore s Montefiore e Medical Center r v Medical Center o i Wayne Av r O 3400 161 3300 v 5 minutes a 309 l d a E o a ll R 176 s E 209 Street Gun Hi t Van Cortlandt W 3398 3298 308 Golf Course 99 E 210 Street Perry Avenue Knox Place Knox 150 3425 North Central 3398 3458 Gates Place Gates Bainbridge Avenue W Bronx Hospital M os ho Bx10 100 M lu W4 Bx10 Bx10 o P Bx16 a W20 W4 6 minutes Bx10 Williamsbridge Oval s r Bx28 h kw W21 W20 Bx16 o a Bx30 Mosholu y W21 Rochambeau Avenue Bx28 Bx34 lu N Bx30 or 41 Avenue Dekalb Bx38 273 Bx34 P th 3300 a Bx38 r Avenue Jerome 80 k ReservoirOval West w Parkway 3400 a 3398 Holt Place y 55 Steuben Avenue 31 Jerome Avenue 3400 D Kossuth Avenue Knox-Gates 3400 9 Van Cortlandt Park South i E 210 Street c Playground 50 k 4048 St. -

Van Cortlandt Park

ORTLANDT C PAR AN mmer Newsl K V g-Su etter rin 200 Sp 9 A Conservancy Grows n January, a group of devoted said Parks Commissioner Benepe. the park to operate at a higher level. Van Cortlandt Park supporters “Seizing this opportune time to build Toward that end, the Conservancy Iincorporated the new non-profit a strong public/private partnership, is exploring how to update both the Van Cortlandt Park Conservancy. the Van Cortlandt Park Conservancy park’s Visitor Survey from 1998 and The Conservancy aims to assist will work with the community to the Master Plan from 1986 and then the Parks Department’s efforts in establish core principles, carefully develop a Strategic Plan to steward maintaining, preserving and pro- guide, and grow the future of the the park over the next decade. The gramming Van Cortlandt Park park for the benefit of the surround- Conservancy is looking critically at through fundraising efforts as well ing community, New Yorkers, and the following long-term needs and as public outreach. The Conservancy visitors alike.” how to move them forward: reno- board members are dedicated, pas- Modeled after the successful vating Woodlawn Playground with sionate park-goers who are distin- public/private partnerships which ADA accessibility; preserving the guished in various professional fields have shepherded the transformation Stadium Building to create indoor and who seek to rally New Yorkers and quality maintenance of Central space for public programming and to make a difference in Van Cort- Park and Prospect Park, the new Van administrative offices; winterizing the landt Park. Cortlandt Park Conservancy is a non- Garage building; renovating the Van “At 1,146 acres, Van Cortlandt profit organization whose goal will be Cortlandt Golf House; and restoring Park is New York City’s fourth largest to build support during these tough the overgrown wetlands of Tib- park and home to popular playing economic times and raise significant betts Brook. -

Public Policies for Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety and Mobility

International Technology Scanning Program September 2010 REVIEW Public Policies for Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety and Mobility An Implementation Project of the Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety and Mobility International Scan SPONSORED BY: IN COOPERATION WITH: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials National Cooperative Highway Research Program Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................... 1 Introduction ..........................................................................1 Findings .............................................................................1 Conclusions ..........................................................................2 Introduction .............................................................................. 3 Purpose of Report .....................................................................3 Scope of Report .......................................................................3 Organization ..........................................................................3 Findings .................................................................................. 4 Methodology .........................................................................4 Listing and Brief Description of Policies .....................................................4 Conclusions .............................................................................. 7 Appendix A | Complete Streets Policies ...................................................