The Politicisation of Election Litigation in Nigeria's Fourth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Parties and Threats of Democratic Reversal in Nigeria

VOLUME 6 NO 2 95 BUILDING DEMOCRACY WITHOUT DEMOCRATS? Political Parties and Threats of Democratic Reversal in Nigeria Said Adejumobi & Michael Kehinde Dr Said Adejumobi is Chief, Public Administration Section, and Coordinator, Africa Governance Report, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa Governance and Public Administration Division, UNECA, PO Box 3005, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Tel: +251 912200066 e-mail: [email protected] Michael Kehinde is a lecturer in the Department of Political Science, Lagos State University PM B 1087, Apapa, Lagos, Nigeria Tel: +234 802 5408439 ABSTRACT Political parties are not only a major agency for the recruitment and enthronement of political leaders in an electoral democracy they are the foundation and a building block of the process of democratic evolution and consolidation. However, the nature and character of the dominant political parties in Nigeria threaten the country’s nascent democratic project. They lack clear ideological orientation, do not articulate alternative worldviews, rarely mobilise the citizenry, and basically adopt anti-democratic methods to confront and resolve democratic issues. Intra- and inter-party electoral competition is fraught with intense violence, acrimony and warfare. Put differently, these parties display all the tendencies and conduct of authoritarianism. The result is that what exists in Nigeria is ‘democratism’, the form and not the substance of an evolving democracy. INTRODUCTION The mass conversion of politicians and political thinkers to the cause of democracy has been one of the most dramatic, and significant, events in 95 96 JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS political history. Even in Ancient Greece, often thought of as the democratic ideal, democracy tended to be viewed in negative terms. -

Legislative Control of the Executive in Nigeria Under the Second Republic

04, 03 01 AWO 593~ By AWOTOKUN, ADEKUNLE MESHACK B.A. (HONS) (ABU) M.Sc. (!BADAN) Thesis submitted to the Department of Public Administration Faculty of Administration in Partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of --~~·---------.---·-.......... , Progrnmme c:~ Petites Subventions ARRIVEE - · Enregistré sous lo no l ~ 1 ()ate :. Il fi&~t. JWi~ DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PUBLIC ADMIJISTRATION) Obafemi Awolowo University, CE\/ 1993 1le-Ife, Nigeria. 2 3 r • CODESRIA-LIBRARY 1991. CERTIFICATION 1 hereby certify that this thesis was prepared by AWOTOKUN, ADEKUNLE MESHACK under my supervision. __ _I }J /J1,, --- Date CODESRIA-LIBRARY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A work such as this could not have been completed without the support of numerous individuals and institutions. 1 therefore wish to place on record my indebtedness to them. First, 1 owe Professer Ladipo Adamolekun a debt of gratitude, as the persan who encouraged me to work on Legislative contrai of the Executive. He agreed to supervise the preparation of the thesis and he did until he retired from the University. Professor Adamolekun's wealth of academic experience ·has no doubt sharpened my outlciok and served as a source of inspiration to me. 1 am also very grateful to Professor Dele Olowu (the Acting Head of Department) under whose intellectual guidance I developed part of the proposai which culminated ·in the final production qf .this work. My pupilage under him i though short was memorable and inspiring. He has also gone through the entire draft and his comments and criticisms, no doubt have improved the quality of the thesis. Perhaps more than anyone else, the Almighty God has used my indefatigable superviser Dr. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 7 November, 2013

FOURTH REpUBLIC 7TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY THIRD SESSION :\'0. 31 675 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 7 November, 2013 1. The House met at 11.39 a.m. Mr Speaker read the Prayers. 2. Votes and Proceedings:' Mr Speaker announced that he had examined and approved the Votes and Proceedings of Wednesday, 6 November, 2013. By unanimous consent, the Votes and Proceedings was adopted. 3. Announcement: (l) Visitors in the Gallery: Mr Speaker recognized the presence of the following visitors: (a) Staff and Students of St Michael's Anglican Diocesan College, Kaduna, Kaduna State; (b) Staff and Students of Queen Science Academy, Kano; (c) Members of Youth Parliament, Kano State Chapter, Kano. (il) Budget Implementation Reports: Mr Speaker read a Communication from Chairman, Committee on Legislative Compliance, disclosing that the following Standing Committees are yet to submit their oversight reports on the implementation of the 2013 Appropriations Act as it affects their respective Ministries, Departments and Agencies: (1) Anti-Corruption, National Ethics and Values (2) Army (3) Aviation (4) Banking and Currency (5) Capital Market and Institution (6) Civil Society and Donor Agencies (7) Commerce (8) Communications and lCT (9) Cooperation and integration in Africa (10) Defence (11) Diaspora (12) Education (13) Electoral Matters (14) Emergency and Disaster Preparedness (15) Environment (16) Federal Character (17) F. C. T. Area Council (18) Finance PRINTED BY NA T10NAL ASSEMBL Y PRESS, ABUJA 676 Thursday, -

Journal of African Elections

VOLUME 7 NO 2 i Journal of African Elections ARTICLES BY Francesca Marzatico Roukaya Kasenally Eva Palmans R D Russon Emmanuel O Ojo David U Enweremadu Christopher Isike Sakiemi Idoniboye-Obu Dhikru AdewaleYagboyaju J Shola Omotola Volume 10 Number 1 June 2011 i ii JOUR na L OF AFRIC an ELECTIO N S Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 11 381 6000 Fax: +27 (0) 11 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] ©EISA 2011 ISSN: 1609-4700 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher Copy editor: Pat Tucker Printed by: Global Print, Johannesburg Cover photograph: Reproduced with the permission of the HAMILL GALLERY OF AFRICAN ART, BOSTON, MA, USA www.eisa.org.za VOLUME 7 NO 2 iii Editor Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg Editorial BOARD Jørgen Elklit, Department of Political Science, University of Aarhus, Denmark Amanda Gouws, Department of Political Science, University of Stellenbosch Abdul Rahman Lamin, UNESCO, Accra Tom Lodge, Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Limerick Khabele Matlosa, UNDP/ECA Joint Governance Initiatives, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Lloyd Sachikonye, Institute of Development Studies, University of Zimbabwe, Harare Gloria Somolekae, National Representative of the W K Kellogg Programme in Botswana and EISA Board member Roger Southall, Department of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg The Journal of African Elections is an interdisciplinary biannual publication of research and writing in the human sciences, which seeks to promote a scholarly understanding of developments and change in Africa. -

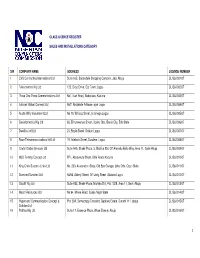

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Ondo State Pocket Factfinder

INTRODUCTION Ondo is one of the six states that make up the South West geopolitical zone of Nigeria. It has interstate boundaries with Ekiti and Kogi states to the north, Edo State to the east, Delta State to the southeast, Osun State to the northwest and Ogun State to the southwest. The Gulf of Guinea lies to its south and its capital is Akure. ONDO: THE FACTS AND FIGURES Dubbed as the Sunshine State, Ondo, which was created on February 3, 1976, has a population of 3,441,024 persons (2006 census) distributed across 18 local councils within a land area of 14,788.723 Square Kilometres. Located in the South-West geo-political zone of Nigeria, Ondo State is bounded in the North by Ekiti/Kogi states; in the East by Edo State; in the West by Oyo and Ogun states, and in the South by the Atlantic Ocean. Ondo State is a multi-ethnic state with the majority being Yoruba while there are also the Ikale, Ilaje, Arogbo and Akpoi, who are of Ijaw extraction and inhabit the riverine areas of the state. The state plays host to 880 public primary schools, and 190 public secondary schools and a number of tertiary institutions including the Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State Polytechnic, Owo, Federal College of Agriculture, Akure and Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo. Arguably, Ondo is one of the most resource-endowed states of Nigeria. It is agriculturally rich with agriculture contributing about 75 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The main revenue yielding crops are cocoa, palm produce and timber. -

Title Page Political Economy of Corruption And

i TITLE PAGE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF CORRUPTION AND REGULATORY AGENCIES IN NIGERIA: A FOCUS ON THE ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CRIME COMMISSION (EFCC), 2000-2010 ii APPROVAL PAGE This is to certify that this research work has met the requirements of the Department of Political of Science, for the Award of a Masters of Science (M.Sc.) Degree in Political Science of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and is approved. BY -------------------------- -------------------------- Prof. Jonah I. Onuoha Date (Project Supervisor) ------------------------- ------------------------- Prof. Obasi Igwe Date Head of Department -------------------------- --------------------------- Prof. Emmanuel O. Ezeani Date Dean of Faculty External Supervisor --------------------------- Date iii DEDICATION To the Well Being and Good Health of my Parents, Mr. and Mrs. Nkemegbunam Anselem Uzendu. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To the Glory of God. I am immensely grateful to my supervisor, Prof. Jonah I. Onuoha whose effort ensured the success of this work. Prof, your cordial relationship with your supervisees and the students at large, speaks much of your professionalism and kind spirit, I cannot thank you enough. To my parents, Mr. and Mrs. Nkemegbunam Anselem Uzendu, my siblings (Henry Chukwujike, Colombus Udochukwu, David Ifeanyi, Rosemary Ifunanya and Augustine Chimobi), my uncles and aunt, (Boniface Uzendu, Okezie Uzendu and Marcy Ndu, nee Uzendu and their respective families) etc, I appreciate all of you for seeing me through to the end of the turnel, as the light shines upon me now. To my room-mates, friends and well-wishers: Ukanwa Oghajie E., Ogbu Ejike C., Adibe Raymond C., Eze Ojukwu Onoh, Okoye Kingsley E., Anya Okoro Ukpai, Ukeka Chinedu D., Dickson Agwuabia, Chris Onyekachi Omenihu, Sampson Eziekeh, Ogochukwu Nnaekee and host of others whose influences have helped to shape my life to better. -

Research Title

THE ROLE OF FEDERALISM IN MITIGATING ETHNIC CONFLICTS IN PLURAL SOCIETIES: NIGERIA AND MALAYSIA IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE CHUKWUNENYE CLIFFORD NJOKU DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND STRATEGIC STUDIES FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2015 THE ROLE OF FEDERALISM IN MITIGATING ETHNIC CONFLICTS IN PLURAL SOCIETIES: NIGERIA AND MALAYSIA IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE CHUKWUNENYE CLIFFORD NJOKU AHA080051 THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFULMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND STRATEGIC STUDIES FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2015 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINIAL LITERARY WORD DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Chukwunenye Clifford Njoku (I/C/Passport No. A06333058) Registration/Matric No: AHA080051 Name of Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Project Paper/Research Report/Dissertation/Thesis (“this Work”): The Role of Federalism in Mitigating Ethnic Conflicts in Plural Societies: Nigeria and Malaysia in Comparative Perspective Field of Study: International Relations I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author/writer of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any except or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this -

Nigeria's Struggle with Corruption Hearing

NIGERIA’S STRUGGLE WITH CORRUPTION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 18, 2006 Serial No. 109–172 Printed for the use of the Committee on International Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.house.gov/international—relations U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27–648PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 21 2002 12:05 Jul 17, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\AGI\051806\27648.000 HINTREL1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa TOM LANTOS, California CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, HOWARD L. BERMAN, California Vice Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York DAN BURTON, Indiana ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American ELTON GALLEGLY, California Samoa ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BRAD SHERMAN, California PETER T. KING, New York ROBERT WEXLER, Florida STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts RON PAUL, Texas GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York DARRELL ISSA, California BARBARA LEE, California JEFF FLAKE, Arizona JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon MARK GREEN, Wisconsin SHELLEY BERKLEY, Nevada JERRY WELLER, Illinois GRACE F. -

Bulletin Produced at St

as ASSOCIATION OF CONCERNED AFRICA SCHOLARS BULLETin Produced at St. Augustine's College, Raleigh, NC 27610-2298 Summer 1991 Number 33 SAHARAN AFRICA THE IMPACT OF THE GULF WAR ON SAHARAN AFRICA, Allan Cooper 1 TUNISIA, Mark Tessler 7 WESTERN SAHARA, Teresa K. Smith de Cherif 9 NIGERIA, George Klay Kieh, Jr. 12 NIGERIA, Emmanuel Oritsejafor 16 DEMOC~CY MOVEMENTS IN AFRICA 19 ANGOLA BENIN CAMEROONS CAPE VERDE COTE D'IVOIRE ETillOPIA GABON GUINEA KENYA MALI SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE SOUTH AFRICA TANZANIA TOGO ZAIRE ZAMBIA ANNOUNCEMENTS 22 AFRICA'S LARGEST COMPANIES 25 ACAS NOMINATIONS FOR ACAS BOARD 26 Editor's Note THE IMPACT OF THE GULF WAR ON SAHARAN AFRICA This issue of the ACAS Bulletin focuses on Saharan Africa, in particular on the consequences and implications to Arab Africa of the U.S.-led assault upon Iraq in January 1991. Although nearly all African states offered some response to the tragic devastation of human and ecological resources in the Persian Gulf, clearly Saharan Africa has been affected more directly from the political and social disruptions brought on by the war. Much already has been written by scholars and the public media concerning the effects of the Gulf War on states such as Egypt and Libya. As a result, the focus of this Bulletin will be on some Saharan countries that have been touched by the war but that are more geographically separated from the Persian Gulf. First, it is important that we provide a summary perspective on a few aftershocks from the war that already are evident in Africa. -

Public Disclosure Authorized

INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION THE INSPECTION PANEL 1818 H Street, N.W. Telephone: (202) 458-5200 Washington, D.C. 20433 Fax: (202) 522-0916 Email: [email protected] Eimi Watanabe Chairperson Public Disclosure Authorized JPN REQUEST RQ13/09 July 16, 2014 MEMORANDUM TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Request for Inspection Public Disclosure Authorized NIGERIA: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions Please find attached a copy of the Memorandum from the Chairperson of the Inspection Panel entitled "Request for Inspection - Nigeria: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) - Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions", dated July 16, 2014 and its attachments. This Memorandum was also distributed to the President of the International Development Association. Public Disclosure Authorized Attachment cc.: The President Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION THE INSPECTION PANEL 1818 H Street, N.W. Telephone: (202) 458-5200 Washington, D.C. 20433 Fax : (202) 522-0916 Email: [email protected] Eimi Watanabe Chairperson IPN REQUEST RQ13/09 July 16, 2014 MEMORANDUM TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Request for Inspection NIGERIA: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions Please find attached a copy of the Memorandum from the Chairperson of the Inspection Panel entitled "Request for Inspection - Nigeria: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P07 J340) - Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions" dated July 16, 2014 and its attachments.