Arcminutes – Minutes of Arc – Abbreviated As 60 Arcmin Or 60´ • Subdivide One Arcminute Into 60 Arcseconds – Seconds of Arc – Abbreviated As 60 Arcsec Or 60”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astronomy 114 Problem Set # 2 Due: 16 Feb 2007 Name

Astronomy 114 Problem Set # 2 Due: 16 Feb 2007 Name: SOLUTIONS As we discussed in class, most angles encountered in astronomy are quite small so degrees are often divded into 60 minutes and, if necessary, minutes in 60 seconds. Therefore to convert an angle measured in degrees to minutes, multiply by 60. To convert minutes to seconds, multiply by 60. To use trigonometric formulae, angles might have to be written in terms of radians. Recall that 2π radians = 360 degrees. Therefore, to convert degrees to radians, multiply by 2π/360. 1 The average angular diameter of the Moon is 0.52 degrees. What is the angular diameter of the moon in minutes? The goal here is to change units from degrees to minutes. 0.52 degrees 60 minutes = 31.2 minutes 1 degree 2 The mean angular diameter of the Sun is 32 minutes. What is the angular diameter of the Sun in degrees? 32 minutes 1 degrees =0.53 degrees 60 minutes 0.53 degrees 2π =0.0093 radians 360 degrees Note that the angular diameter of the Sun is nearly the same as the angular diameter of the Moon. This similarity explains why sometimes an eclipse of the Sun by the Moon is total and sometimes is annular. See Chap. 3 for more details. 3 Early astronomers measured the Sun’s physical diameter to be roughly 109 Earth diameters (1 Earth diameter is 12,750 km). Calculate the average distance to the Sun using trigonometry. (Hint: because the angular size is small, you can make the approximation that sin α = α but don’t forget to express α in radians!). -

Calculating Growing Degree Days by Jim Nugent District Horticulturist Michigan State University

Calculating Growing Degree Days By Jim Nugent District Horticulturist Michigan State University Are you calculating degree day accumulations and finding your values don't match the values being reported by MSU or your neighbor's electronic data collection unit? There is a logical reason! Three different methods are used to calculate degree days; i.e., 1) Averaging Method; 2) Baskerville-Emin (BE) Method; and 3) Electronic Real-time Data Collection. All methods attempt to calculate the heat accumulation above a minimum threshold temperature, often referred to the base temperature. Once both the daily maximum and minimum temperatures get above the minimum threshold temperature, (i.e., base temperature of 42degrees, 50degrees or whatever other base temperature of interest) then all methods are fairly comparable. However, differences do occur and these are accentuated in an exceptionally long period of cool spring temperatures, such as we experienced this year. Let me briefly explain: 1. Averaging Method: Easy to calculate Degree Days(DD) = Average daily temp. - Base Temp. = (max. + min.) / 2 - Base temp. If answer is negative, assume 0. Example: Calculate DD Base 50 given 65 degrees max. and 40 degrees min. Avg. = (65 + 40) / 2 = 52.5 degrees DD base 50 = 52.5 - 50 = 2.5 degrees. But look what happens given a maximum of 60 degrees and a minimum of 35 degrees: Avg. = (60 + 35) / 2 = 47.5 DD base 50 = 47.5 - 50 = -2.5 = 0 degrees. The maximum temperature was higher than the base of 50° , but no degree days were accumulated. A grower called about the first of June reporting only about 40% of the DD50 that we have recorded. -

Angles ANGLE Topics • Coterminal Angles • Defintion of an Angle

Angles ANGLE Topics • Coterminal Angles • Defintion of an angle • Decimal degrees to degrees, minutes, seconds by hand using the TI-82 or TI-83 Plus • Degrees, seconds, minutes changed to decimal degree by hand using the TI-82 or TI-83 Plus • Standard position of an angle • Positive and Negative angles ___________________________________________________________________________ Definition: Angle An angle is created when a half-ray (the initial side of the angle) is drawn out of a single point (the vertex of the angle) and the ray is rotated around the point to another location (becoming the terminal side of the angle). An angle is created when a half-ray (initial side of angle) A: vertex point of angle is drawn out of a single point (vertex) AB: Initial side of angle. and the ray is rotated around the point to AC: Terminal side of angle another location (becoming the terminal side of the angle). Hence angle A is created (also called angle BAC) STANDARD POSITION An angle is in "standard position" when the vertex is at the origin and the initial side of the angle is along the positive x-axis. Recall: polynomials in algebra have a standard form (all the terms have to be listed with the term having the highest exponent first). In trigonometry, there is a standard position for angles. In this way, we are all talking about the same thing and are not trying to guess if your math solution and my math solution are the same. Not standard position. Not standard position. This IS standard position. Initial side not along Initial side along negative Initial side IS along the positive x-axis. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Applications of Geometry and Trigonometry

P1: FXS/ABE P2: FXS 9780521740517c14.xml CUAU031-EVANS September 6, 2008 13:36 CHAPTER 14 MODULE 2 Applications of geometry and trigonometry How do we apply trigonometric techniques to problems involving angles of depression and elevation? How do we apply trigonometric techniques to problems involving bearings? How do we apply trigonometric techniques to three-dimensional problems? How do we draw and interpret contour maps? How do we draw and interpret scale drawings? 14.1 Angles of elevation and depression, bearings, and triangulation Angles of elevation and depression The angle of elevation is the angle The angle of depression is the angle between the horizontal and a between the horizontal and a direction below direction above the horizontal. the horizontal. eye level line of sight angle of depression line of sight eye level cliff angle of elevation SAMPLEboat Cambridge University Press • Uncorrected Sample pages • 978-0-521-61328-6 • 2008 © Jones, Evans, Lipson TI-Nspire & Casio ClassPad material in collaboration with Brown410 and McMenamin P1: FXS/ABE P2: FXS 9780521740517c14.xml CUAU031-EVANS September 6, 2008 13:36 Chapter 14 — Applications of geometry and trigonometry 411 Bearings The three-figure bearing (or compass bearing) is the direction measured clockwise from north. The bearing of A from O is 030◦. The bearing of C from O is 210◦. The bearing of B from O is 120◦. The bearing of D from O is 330◦. N D N A 30° 330° E 120° E W O 210° W O B C S S Example 1 Angle of depression The pilot of a helicopter flying at 400 m observes a small boat at an angle of depression of 1.2◦. -

1. What Is the Radian Measure of an Angle Whose Degree Measure Is 72◦ 180◦ 72◦ = Πradians Xradians Solving for X 72Π X = Radians 180 2Π X = Radians 5 Answer: B

1. What is the radian measure of an angle whose degree measure is 72◦ 180◦ 72◦ = πradians xradians Solving for x 72π x = radians 180 2π x = radians 5 Answer: B 2. What is the length of AC? Using Pythagorean Theorem: 162 + b2 = 202 256 + b2 = 400 b2 = 144 b = 12 Answer: E 3. one solution to z2 + 64 = 0 is z2 + 64 = 0 z2 = −64 p p z2 = −64 Since there is a negative under the radical, we get imaginary roots. Thus z = −8i or z = +8i Answer: A 4. Simplifying: p 36x10y12 − 36y12 = p36y12 (x10 − 1) p = 36y12p(x10 − 1) p = 6y6 x10 − 1 Answer: C 1 5. Simplifying: 1 1 1 1 1 −3 9 6 3 −3 9 6 27a b c = 27 3 a 3 b 3 c 3 = 3a−1b3c2 3b3c2 = a Answer: C 6. Solving for x: p 8 + x + 14 = 12 p x + 14 = 12 − 8 p x + 14 = 4 p 2 x + 14 = 42 x + 14 = 16 x = 16 − 14 x = 2 Answer: C 7. Simplify x2 − 9 (x + 1)2 2x − 6 × ÷ x2 − 1 (2x + 3)(x + 3) 1 − x Rewrite as a multiplication. x2 − 9 (x + 1)2 1 − x × x2 − 1 (2x + 3)(x + 3) 2x − 6 Simplify each polynomial (x − 3)(x + 3) (x + 1)(x + 1) 1 − x × (x − 1)(x + 1) (2x + 3)(x + 3) 2(x − 3) Canceling like terms (x + 1) − 2(2x + 3) Answer: C 2 8. Simplifying: 1 11 x−5 11 + 2 2 + 2 x−5 (x−5) = (x−5) (x−5) x + 1 x + 1 x−5+11 2 = (x−5) x + 1 x+6 2 = (x−5) x + 1 x + 6 = (x − 5)2(x + 1) Answer: B 9. -

4.1 – Radian and Degree Measure

4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Accelerated Pre-Calculus Mr. Niedert Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 1 / 27 2 Radian Measure 3 Degree Measure 4 Applications 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure 1 Angles Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 2 / 27 3 Degree Measure 4 Applications 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure 1 Angles 2 Radian Measure Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 2 / 27 4 Applications 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure 1 Angles 2 Radian Measure 3 Degree Measure Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 2 / 27 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure 1 Angles 2 Radian Measure 3 Degree Measure 4 Applications Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 2 / 27 The starting position of the ray is the initial side of the angle. The position after the rotation is the terminal side of the angle. The vertex of the angle is the endpoint of the ray. Angles An angle is determine by rotating a ray about it endpoint. Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 3 / 27 The position after the rotation is the terminal side of the angle. The vertex of the angle is the endpoint of the ray. Angles An angle is determine by rotating a ray about it endpoint. The starting position of the ray is the initial side of the angle. Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 3 / 27 The vertex of the angle is the endpoint of the ray. -

Planetary Diameters in the Sürya-Siddhänta DR

Planetary Diameters in the Sürya-siddhänta DR. RICHARD THOMPSON Bhaktivedanta Institute, P.O. Box 52, Badger, CA 93603 Abstract. This paper discusses a rule given in the Indian astronomical text Sürya-siddhänta for comput- ing the angular diameters of the planets. I show that this text indicates a simple formula by which the true diameters of these planets can be computed from their stated angular diameters. When these computations are carried out, they give values for the planetary diameters that agree surprisingly well with modern astronomical data. I discuss several possible explanations for this, and I suggest that the angular diameter rule in the Sürya-siddhänta may be based on advanced astronomical knowledge that was developed in ancient times but has now been largely forgotten. In chapter 7 of the Sürya-siddhänta, the 13th çloka gives the following rule for calculating the apparent diameters of the planets Mars, Saturn, Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus: 7.13. The diameters upon the moon’s orbit of Mars, Saturn, Mercury, and Jupiter, are de- clared to be thirty, increased successively by half the half; that of Venus is sixty.1 The meaning is as follows: The diameters are measured in a unit of distance called the yojana, which in the Sürya-siddhänta is about five miles. The phrase “upon the moon’s orbit” means that the planets look from our vantage point as though they were globes of the indicated diameters situated at the distance of the moon. (Our vantage point is ideally the center of the earth.) Half the half of 30 is 7.5. -

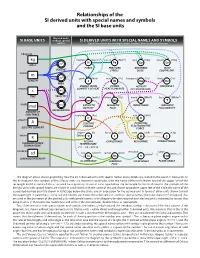

Relationships of the SI Derived Units with Special Names and Symbols and the SI Base Units

Relationships of the SI derived units with special names and symbols and the SI base units Derived units SI BASE UNITS without special SI DERIVED UNITS WITH SPECIAL NAMES AND SYMBOLS names Solid lines indicate multiplication, broken lines indicate division kilogram kg newton (kg·m/s2) pascal (N/m2) gray (J/kg) sievert (J/kg) 3 N Pa Gy Sv MASS m FORCE PRESSURE, ABSORBED DOSE VOLUME STRESS DOSE EQUIVALENT meter m 2 m joule (N·m) watt (J/s) becquerel (1/s) hertz (1/s) LENGTH J W Bq Hz AREA ENERGY, WORK, POWER, ACTIVITY FREQUENCY second QUANTITY OF HEAT HEAT FLOW RATE (OF A RADIONUCLIDE) s m/s TIME VELOCITY katal (mol/s) weber (V·s) henry (Wb/A) tesla (Wb/m2) kat Wb H T 2 mole m/s CATALYTIC MAGNETIC INDUCTANCE MAGNETIC mol ACTIVITY FLUX FLUX DENSITY ACCELERATION AMOUNT OF SUBSTANCE coulomb (A·s) volt (W/A) C V ampere A ELECTRIC POTENTIAL, CHARGE ELECTROMOTIVE ELECTRIC CURRENT FORCE degree (K) farad (C/V) ohm (V/A) siemens (1/W) kelvin Celsius °C F W S K CELSIUS CAPACITANCE RESISTANCE CONDUCTANCE THERMODYNAMIC TEMPERATURE TEMPERATURE t/°C = T /K – 273.15 candela 2 steradian radian cd lux (lm/m ) lumen (cd·sr) 2 2 (m/m = 1) lx lm sr (m /m = 1) rad LUMINOUS INTENSITY ILLUMINANCE LUMINOUS SOLID ANGLE PLANE ANGLE FLUX The diagram above shows graphically how the 22 SI derived units with special names and symbols are related to the seven SI base units. In the first column, the symbols of the SI base units are shown in rectangles, with the name of the unit shown toward the upper left of the rectangle and the name of the associated base quantity shown in italic type below the rectangle. -

Radio Astronomy

Edition of 2013 HANDBOOK ON RADIO ASTRONOMY International Telecommunication Union Sales and Marketing Division Place des Nations *38650* CH-1211 Geneva 20 Switzerland Fax: +41 22 730 5194 Printed in Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 730 6141 Geneva, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-92-61-14481-4 Edition of 2013 Web: www.itu.int/publications Photo credit: ATCA David Smyth HANDBOOK ON RADIO ASTRONOMY Radiocommunication Bureau Handbook on Radio Astronomy Third Edition EDITION OF 2013 RADIOCOMMUNICATION BUREAU Cover photo: Six identical 22-m antennas make up CSIRO's Australia Telescope Compact Array, an earth-rotation synthesis telescope located at the Paul Wild Observatory. Credit: David Smyth. ITU 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. - iii - Introduction to the third edition by the Chairman of ITU-R Working Party 7D (Radio Astronomy) It is an honour and privilege to present the third edition of the Handbook – Radio Astronomy, and I do so with great pleasure. The Handbook is not intended as a source book on radio astronomy, but is concerned principally with those aspects of radio astronomy that are relevant to frequency coordination, that is, the management of radio spectrum usage in order to minimize interference between radiocommunication services. Radio astronomy does not involve the transmission of radiowaves in the frequency bands allocated for its operation, and cannot cause harmful interference to other services. On the other hand, the received cosmic signals are usually extremely weak, and transmissions of other services can interfere with such signals. -

Transit of Venus M

National Aeronautics and Space Administration The Transit of Venus June 5/6, 2012 HD209458b (HST) The Transit of Venus June 5/6, 2012 Transit of Venus Mathof Venus Transit Top Row – Left image - Photo taken at the US Naval Math Puzzler 3 - The duration of the transit depends Observatory of the 1882 transit of Venus. Middle on the relative speeds between the fast-moving image - The cover of Harpers Weekly for 1882 Venus in its orbit and the slower-moving Earth in its showing children watching the transit of Venus. orbit. This speed difference is known to be 5.24 km/sec. If the June 5, 2012, transit lasts 24,000 Right image – Image from NASA's TRACE satellite seconds, during which time the planet moves an of the transit of Venus, June 8, 2004. angular distance of 0.17 degrees across the sun as Middle - Geometric sketches of the transit of Venus viewed from Earth, what distance between Earth and by James Ferguson on June 6, 1761 showing the Venus allows the distance traveled by Venus along its shift in the transit chords depending on the orbit to subtend the observed angle? observer's location on Earth. The parallax angle is related to the distance between Earth and Venus. Determining the Astronomical Unit Bottom – Left image - NOAA GOES-12 satellite x-ray image showing the Transit of Venus 2004. Middle Based on the calculations of Nicolas Copernicus and image – An observer of the 2004 transit of Venus Johannes Kepler, the distances of the known planets wearing NASA’s Sun-Earth Day solar glasses for from the sun could be given rather precisely in terms safe viewing. -

Alpha Orionis (Betelgeuse)

AAVSO: Alpha Ori, December 2000 Variable Star Of The Month Variable Star Of The Month December, 2000: Alpha Orionis (Betelgeuse) Atmosphere of Betelgeuse - Alpha Orionis Hubble Space Telescope - Faint Object Camera January 15, 1996; A. Dupree (CfA), NASA, ESA From the city or country sky, from almost any part of the world, the majestic figure of Orion dominates overhead this time of year with his belt, sword, and club. High in his left shoulder (for those of us in the northern hemisphere) is the great red pulsating supergiant, Betelgeuse (Alpha Orionis 0549+07). Recently acquiring fame for being the first star to have its atmosphere directly imaged (shown above), Alpha Orionis has captivated observers’ attention for centuries. Betelgeuse's variability was first noticed by Sir John Herschel in 1836. In his Outlines of Astronomy, published in 1849, Herschel wrote “The variations of Alpha Orionis, which were most striking and unequivocal in the years 1836-1840, within the years since elapsed became much less conspicuous…” In 1849 the variations again began to increase in amplitude, and in December 1852 it was thought by Herschel to be “actually the largest [brightest] star in the northern hemisphere”. Indeed, when at maximum, Betelgeuse sometimes rises to magnitude 0.4 when it becomes a fierce competitor to Rigel; in 1839 and 1852 it was thought by some observers to be nearly the equal of Capella. Observations by the observers of the AAVSO indicate that Betelgeuse probably reached magnitude 0.2 in 1933 and again in 1942. At minimum brightness, as in 1927 and 1941, the magnitude may drop below 1.2.