Integrating Indigenous Knowledge System to Sustainable Agricultural Practices of Higaonon Tribein Claveria, Misamis Oriental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landcare in the Philippines STORIES of PEOPLE and PLACES

Landcare S TORIES OF PEOPLEAND PLACES Landcare in in the Philippines the Philippines STORIES OF PEOPLE AND PLACES Edited by Jenni Metcalfe www.aciar.gov.au 112 Landcare in the Philippines STORIES OF PEOPLE AND PLACES Edited by Jenni Metcalfe Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research ACIAR Monograph 112 i CanberraLandcare 2004 in the Philippines Edited by J. Metcalfe ACIAR Monograph 112 (printed version published in 2004) ACIAR MONOGRAPH SERIES This series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or material deemed relevant to ACIAR’s research and development objectives. The series is distributed internationally, with an emphasis on developing countries This book has been produced by the Philippines – Australia Landcare project, a partnership between: • The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) • World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) • SEAMEO Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA) • Agencia Española de Cooperacion Internacional (AECI) • Department of Primary Industries & Fisheries – Queensland Government (DPIF) • University of Queensland • Barung Landcare Association • Department of Natural Resources Mines and Energy – Queensland Government (DNRME) The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its primary mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing -

Euphemisms for Taboo Words: Iliganon’S Sociolinguistical Approach for Social Harmony

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 6, No. 4, December 2019 doi:10.30845/jesp.v6n4p7 Euphemisms for Taboo Words: Iliganon’s Sociolinguistical Approach for Social Harmony Prof. Marilyn Tampos-Villadolid Department of Social Sciences and Humanities College of Education and Social Sciences Mindanao State University-Naawan 9023 Naawan, Misamis Oriental, Philippines Dr. Angelina Lozada Santos Department of Filipino and Other Languages College of Arts and Social Sciences Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology 9200 Iligan City, Lanao del Norte, Philippines Abstract Iliganon’s are local residents of Iligan City in Mindanao Island in southern Philippines. They are conservative and generally peace-loving. They do not provoke or start a discord or use a language that is socially unacceptable. Hence, words that have negative effect to listeners are taboo, and to push through the message they want to convey, euphemisms are used. Quota, purposive, and convenience samplings were utilized to attain the desired number of respondents classified as professionals and non-professionals, male and female. The open- ended questionnaire used contained a list of local taboo words which have heavy sexual meanings, repulsive dirt emanating from the body, and other words that evoked aversion to the sensibility of an ordinary person. The respondents listed the euphemisms they commonly used when speaking about these taboo words. Frequency count, percentage, ranking, and chi-square were used to interpret the data. Results showed that the respondents used 10,529 euphemisms for 62 taboo words under six groups. Both variables were found significant at .05 level of chi-square. Euphemisms were effectively utilized to conceal the socially unacceptable words in Iliganon’s speech. -

Province of Bukidnon

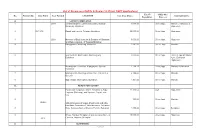

Department of Environment and Natural Resources MINES & GEOSCIENCES BUREAU Regional Office No. X Macabalan, Cagayan de Oro City DIRECTORY OF PRODUCING MINES AND QUARRIES IN REGION 10 CALENDAR YEAR 2017 PROVINCE OF BUKIDNON Head Office Mine Site Mine Site Municipality/ Head Office Mailing Head Office Fax Head Office E- Head Office Mine Site Mailing Mine Site Type of Date Date of Area Municipality, Year Region Mineral Province Commodity Contractor Operator Managing Official Position Telephone Telephone Email Permit Number Barangay Status TIN City Address No. mail Address Website Address Fax Permit Approved Expirtion (has.) Province No. No. Address Commercial Sand and Gravel San Isidro, Valencia San Isidro, Valencia CSAG-2001-17- Valencia City, Non-Metallic Bukidnon Valencia City Sand and Gravel Abejuela, Jude Abejuela, Jude Permit Holder City 0926-809-1228 City 24 Bukidnon Operational 2017 10 CSAG 12-Jul-17 12-Jul-18 1 ha. San Isidro Manolo Manolo JVAC & Damilag, Manolo fedemata@ya Sabangan, Dalirig, CSAG-2015-17- Fortich, 931-311- 2017 10 Non-Metallic Bukidnon Fortich Sand and Gravel VENRAY Abella, Fe D. Abella, Fe D. Permit Holder Fortich, Bukidnon 0905-172-8446 hoo.com Manolo Fortich CSAG 40 02-Aug-17 02-Aug-18 1 ha. Dalirig Bukidnon Operational 431 Nabag-o, Valencia agbayanioscar Nabag-o, Valencia Valencia City, 495-913- 2017 10 Non-Metallic Bukidnon Valencia City Sand and Gravel Agbayani, Oscar B. Agbayani, Oscar B. Permit Holder City 0926-177-3832 [email protected] City CSAG CSAG-2017-09 08-Aug-17 08-Aug-18 2 has. Nabag-o Bukidnon Operational 536 Old Nongnongan, Don Old Nongnongan, Don CSAG-2006- Don Carlos, 2017 10 Non-Metallic Bukidnon Don Carlos Sand and Gravel UBI Davao City Alagao, Consolacion Alagao, Consolacion Permit Holder Calrlos Carlos CSAG 1750 11-Oct-17 11-Oct-18 1 ha. -

Journal of Environment and Aquatic Resources. 5: 43-60 (2020)

1 Journal of Environment and Aquatic Resources. 5: 43-60 (2020) doi: 10.48031/msunjear.2020.05.04 Socio-Economic Condition Among the Fisherfolks in Iligan Bay, Northern Mindanao, Philippines Mariefe B. Quiñones1*,Cesaria R. Jimenez1, Harry Kenn T. Dela Rosa1, Margarita C. Paghasian2, Jeanette J. Samson1, Dionel L. Molina1 and Jerry P. Garcia1 1Mindanao State University at Naawan, Naawan, Misamis Oriental 2Mindanao State University- Maigo School of Arts and Trades, Maigo, Lanao del Norte *corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT A one-year assessment on the fishery and reproductive dynamics of roundscads was conducted from September 2017 to October 2018 to determine the status of the fishery in Iligan Bay, including information on the socio-economic condition of the fishers in the Bay. The study used Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) conducted between September to October 2017 and secondary data to gather information on the number of fishers, type and number of boats, type of fishing methods and number of fishing gears, income, expenditure distribution, and non-fishery-based income sources as well as the fishers’ perception on issues and problems affecting their catches. The Bay had an estimated 15,357 fishers across all sites from 17 municipalities and two cities based on focus group discussions. Most fishers were from the province of Misamis Occidental or representing about 74% of the entire fisher population operating in the Bay. Iligan Bay has an artisanal or subsistence type of fisheries where most fishers rely mainly on traditional methods to harvest fish resources except for the commercial fishers operating the ring net or “kubkuban”. -

Hatchery and Pond Culture of Macrobrachium Rosenbergii in Northern Mindanao

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center, Aquaculture Department Institutional... SEAFDEC/AQD Institutional Repository (SAIR) Title Hatchery and pond culture of Macrobrachium rosenbergii in Northern Mindanao Author(s) Dejarme, Henry E. Citation Issue Date 2005 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10862/678 This document is downloaded at: 2013-07-02 01:28:33 CST http://repository.seafdec.org.ph use functions to include ulang seed production; (4) promotion and/or dispersal of ulang postlarvae throughout the country; (5) establishment of pilot techno-demo farms in collaboration with private cooperators, local government units and the academe; (6) awareness creation on the part of the fisherfolk and/or entrepreneurs on the potentials of ulang culture; (7) development of a code of conduct for sustainable ulang production; (8) refinement of the rice-prawn technology and promotion of the technology throughout the country; and (9) intensive nationwide information dissemination campaign on the economics of ulang aquaculture. With inputs coming from the IRAP collaborative research, the Philippines is assured of the sustainability of prawn aquaculture in the country. Hatchery and Pond Culture of Macrobrachium rosenbergii in Northern Mindanao Dr. Henry E. Dejarme of the MSU at Naawan. The history and status of hatchery and grow-out culture of Macrobrachium rosenbergii is not based on a study nor a survey. Rather, it was derived mainly from his on-the-job experience and information gathered during visits of culture sites or shared by other workers in the culture of freshwater prawn in Northern Mindanao. -

List of On-Process Cadts in Region 10 (Direct CADT Applications) Est

List of On-process CADTs in Region 10 (Direct CADT Applications) Est. IP CADC No./ No. Petition No. Date Filed Year Funded LOCATION Est. Area (Has.) Claimant ICC/s Population Process A.6. 03/25/95 Kibalagon SURVEY Lot COMPLETED2 (CMU) 601.00 Direct App. Manobo-Talaandig 1. 2004 Central Mindanao University (CMU), Musuan, 3,080.00 Direct App. Manobo, Talaandig & Maramag, Bukidnon Higa-onon 2. 05/13/02 Basak and Lantud, Talakag, Bukidnon 20,000.00 Direct App. Higa-onon 3. 2008 Maecate of Brgy, Laculac & Sagaran of Baungon 5,000.00 Direct App. Higaonon and Dagondalahon of Talakag,Bukidnon 4. Danggawan, Maramag, Bukidnon 1,941.92 Direct App. Manobo 5. Guinawahan, Bontongan, Impasug-ong, 3,000.00 Direct App. Heirs of Apo Bartolome Bukidnon Ayoc (Bukidnon- Higaonon) 6. Merangeran, Lumintao, Kipaypayon, Quezon 7,294.73 Direct App. Manobo-Kulamanen Bukidnon 7. Banlag & Sto. Domingo of Quezon , Valencia & 2,154.00 Direct App. Manobo Quezon 8. San nicolas, Don Carlos, Bukidnon 1,401.00 Direct App. Manobo B. READY FOR SURVEY 1. Palabukan (Tagiptip),Libona, Bukidnon & Brgy. 11,193.54 AO1 Higa-onon Cugman (Malasag), and Agusan, Cag de Oro City 2. 120.00 Direct App. Manobo 1/14/02 Sitio Kiramanon of Brgys. Panalsalan and Sitio Kawilihan Dagumbaan, Mun Maramag, Bukidnon 3. Brgy. Santiago Mun of Manolo Fortich, Bukidnon 1,450.00 Direct App. Bukidnon 4. Brgys. Plaridel, Hinaplanon and Gumaod, Mun. of 10,000.00 Direct App. Higaonon 2012 Claveria, Misamis Oriengtal C. SUSPENDED Page 1 of 6 Est. IP CADC No./ No. Petition No. Date Filed Year Funded LOCATION Est. -

REGION 10 Address: Baloy, Cagayan De Oro City Office Number: (088) 855 4501 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: John Robert R

REGION 10 Address: Baloy, Cagayan de Oro City Office Number: (088) 855 4501 Email: [email protected] Regional Director: John Robert R. Hermano Mobile Number: 0966-6213219 Asst. Regional Director: Rafael V Marasigan Mobile Number: 0917-1482007 Provincial Office : BUKIDNON Address : Capitol Site, Malaybalay, Bukidnon Office Number : (088) 813 3823 Email Address : [email protected] Provincial Manager : Leo V. Damole Mobile Number : 0977-7441377 Buying Station : GID Aglayan Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Joyce Sale Mobile Number : 0917-1150193 Service Areas : Malaybalay, Cabanglasan, Sumilao and Impsug-ong Buying Station : GID Valencia Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Rhodnalyn Manlawe Mobile Number : 0935-9700852 Service Areas : Valencia, San Fernando and Quezon Buying Station : GID Kalilangan Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Catherine Torregosa Mobile Number : 0965-1929002 Service Areas : Kalilangan Buying Station : GID Wao Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Catherine Torregosa Mobile Number : 0965-1929002 Service Areas : Wao, and Banisilan, North Cotabato Buying Station : GID Musuan Location : Warehouse Supervisor : John Ver Chua Mobile Number : 0975-1195809 Service Areas : Musuan, Quezon, Valencia, Maramag Buying Station : GID Maramag Location : Warehouse Supervisor : Rodrigo Tobias Mobile Number : 0917-7190363 Service Areas : Pangantucan, Kibawe, Don Carlos, Maramag, Kitaotao, Kibawe, Damulog Provincial Office : CAMIGUIN Address : Govt. Center, Lakas, Mambajao Office Number : (088) 387 0053 Email Address : [email protected] -

Forest Plant Community and Ethnomedicinal Study Towards Biodiversity Conservation of an Ancestral Land in Northern Mindanao

Forest Plant Community and Ethnomedicinal Study towards Biodiversity Conservation of an Ancestral Land in Northern Mindanao Mariche B. Bandibas1 and Proserpina G. Roxas2 1Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau Department of Environment and Natural Resources Los Baños, College, Laguna 2Mindanao State University at Naawan, Naawan, Misamis Oriental [email protected] ABSTRACT The dependence of many rural communities in the Philippines on herbal medicine represents a long history of human interactions with the environment. The use of plant resources as indigenous sources of cure for a wide variety of ailments has been part of traditional cultures, however, urban development and its sprawl into rural areas has somehow eroded this traditional practice. An assessment of the forest plant community within the vicinity of Lake Danao in the upland area of Naawan, Misamis Oriental was conducted to evaluate the status of biodiversity and ethnomedicinal value of plant resources and determine the community’s perceptions toward forest conservation. Standard methods in assessment of plant community structure were adopted. Knowledge, perceptions, and attitude of the respondents towards forest resources and ethnomedicinal plants were obtained through semi-structured interview. Extracts from five species of medicinal plants were tested for antibacterial action against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus using the disc diffusion method and using chloramphenicol as positive control. Sixty one species of trees, saplings and herbs belonging to 29 families were recorded in the survey. Acacia mangium, Leukosyke capitellata and Nephrolepis hirstula were the most numerically important plant species. Thirty-three out of 61 species have medicinal value to local residents which are used to treat various disorders. -

SOIL Ph MAP ( Key Rice Areas ) Sugbongcogon

8 2 124°15' 124°30' 124°45' 125°0' 125°15' 125°30' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S D E PA R T M E N T O F A G R IIC U LT U R E BUREAU OF SOILS AND Magsaysay WATER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Road Cor. Visayas Ave., Diliman, Quezon City Balingoan 9°0' Talisayan 9°0' Kinogitan SOIL pH MAP ( Key Rice Areas ) Sugbongcogon PROVINCE OF MISAMIS ORIENTAL Binuangan G I N G O O G B A Y ° Medina SCALE 1:310,000 0 2 4 6 8 10 Kilometers Projection : Transverse Mercator Datum : PRS 1992 DISCLAIMER : All political boundaries are not authoritative Salay Province of Agusan Del Norte Gingoog Lagonglong M I N D A N A O S E A 8°45' Balingasag 8°45' B A L I N G A S A G B A Y Jasaan C A B U L I C B A Y Area estimated based on actual field survey, other information from DA-RFO's, MA's NIA Service Area, NAMRIA Land Cover (2010) and BSWM Land Use System Map. Claveria Gitagum A L U B I J I D B A Y Villanueva Province of Agusan Del Sur Laguindingan El Salvador M A C A L A J A R B A Y Libertad Alubijid Tagoloan Opol 8°30' Initao 8°30' Cagayan De Oro I L I G A N B A Y LOCATION MAP Naawan 20° Camiguin Manticao 9° Province of Bukidnon LUZON 15° MISAMIS ORIENTAL VISAYAS 10° Lanao Bukidnon Lugait del Norte Lanao MINDANAO del Sur 5° 8° 125° 120° 125° MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION CONVENTIONAL SIGNS SOURCES OF INFORMATION:Topographic information taken from NAMRIA Topographic Map at a scale of 1:50,000. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BUKIDNON

2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BUKIDNON 1,299,192 BAUNGON 32,868 Balintad 660 Buenavista 1,072 Danatag 2,585 Kalilangan 883 Lacolac 685 Langaon 1,044 Liboran 3,094 Lingating 4,726 Mabuhay 1,628 Mabunga 1,162 Nicdao 1,938 Imbatug (Pob.) 5,231 Pualas 2,065 Salimbalan 2,915 San Vicente 2,143 San Miguel 1,037 DAMULOG 25,538 Aludas 471 Angga-an 1,320 Tangkulan (Jose Rizal) 2,040 Kinapat 550 Kiraon 586 Kitingting 726 Lagandang 1,060 Macapari 1,255 Maican 989 Migcawayan 1,389 New Compostela 1,066 Old Damulog 1,546 Omonay 4,549 Poblacion (New Damulog) 4,349 Pocopoco 880 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Sampagar 2,019 San Isidro 743 DANGCAGAN 22,448 Barongcot 2,006 Bugwak 596 Dolorosa 1,015 Kapalaran 1,458 Kianggat 1,527 Lourdes 749 Macarthur 802 Miaray 3,268 Migcuya 1,075 New Visayas 977 Osmeña 1,383 Poblacion 5,782 Sagbayan 1,019 San Vicente 791 DON CARLOS 64,334 Cabadiangan 460 Bocboc 2,668 Buyot 1,038 Calaocalao 2,720 Don Carlos Norte 5,889 Embayao 1,099 Kalubihon 1,207 Kasigkot 1,193 Kawilihan 1,053 Kiara 2,684 Kibatang 2,147 Mahayahay 833 Manlamonay 1,556 Maraymaray 3,593 Mauswagon 1,081 Minsalagan 817 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, -

Adaptive Measures to Climate Change Among the Higaonon Communities in Naawan and Initao,Misamis Oriental, Mindanao, Philippines

American Journal of Social Sciences, Arts and Literature Vol. 4, No. 1, January 2017, pp. 1 - 7, E - ISSN: 2334 - 0037 Available online at http://ajssal.com/ Research article Adaptive measures to climate change among the Higaonon communities in Naawan and Initao,Misamis Oriental, Mindanao, Philippines Geralyn D. Dela Peña 1,9 , QuiniGine W. Areola 2,9 , Cristobal C. Tanael 3,9 , Florence C. Paler 4,9 , Dinnes M. Cortez 5,9 , AldrinB. Librero 5,9 , Jan Rey M. Flores 5,9 , John Philip A. Viajedor 6,9 , Juvelyn B. Lugatiman 7,9 , Ruth S. Talingting 8,9 and SonnieA. Vedra 1,9 1 Institute of Fisheries Research and Development, Mindanao State University at Naawan, Naawan, Misamis Oriental 2 Initao College, Initao, Misamis Oriental 3 City Agriculture Office, Iligan city 4 Department of Trade and Industry, Region X 5 Department of Social Welfare and Development, Region X 6 City Environment and Natural Resources Office, Oroquieta City 7 Dep artment of Environment and Natural Resources, Region X 8 Department of Education, Region X 9 School of Graduate Studies, Mindanao State University at Naawan, 9023 Naawan,Misamis Oriental, Philippines This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License . ______________________________________________ Abstract Traditional knowledge systems of indigenous peoples are now acknowledged globally as crucial in combatting climate change.Thus, this study was conducted to determine the adaptive measures to climate change undertaken by theHigaonon communities within the hinterlands of Initao and Naawan, Misamis Oriental, Philippines. Collections of data were done th rough Focused Group Discussion (FGD) and Key Informant Interview (KII) using semi - structured open - ended questionnaires. -

Assessing Macroinvertebrate Population Inhabiting the Talabaan River, Naawan, Misamis Oriental, Philippines

World Journal of Environmental and Agricultural Sciences Vol. 2, No. 1, December 2017, pp. 1- 5 Available online at http://www.wjeas.com/ Research article ASSESSING MACROINVERTEBRATE POPULATION INHABITING THE TALABAAN RIVER, NAAWAN, MISAMIS ORIENTAL, PHILIPPINES Michael James O. Baclayon9, John Philip A. Viajedor1,9, Cristobal C. Tanael2,9, Juvelyn B. Lugatiman3,9 , Dinnes M. Cortes4,9, Aldrin B. Librero4,9, Jan Rey M. Flores5,9, Florante G. Requina6,9, Romersita D. Dadayan7,9, QuiniGine W. Areola8,9, Sotico P. Micabalo8,9, Ruth S. Talingting8,9, Geralyn D. Dela Peña,9 and Sonnie A. Vedra9 1 University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines 2City Agriculture Office, Iligan City 3 Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Region X 4 Department of Social Welfare and Development, Region X 5 Caraga State University 6 Northwestern Mindanao State College of Science and Technology 7 Mindanao State University, Main Campus, Marawi City 8 Department of Education, Region X 9 School of Graduate Studies, Mindanao State University at Naawan, 9023, Naawan, Misamis Oriental, Philippines This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ______________________________________________ ABSTRACT Water pollution is rampant due to uncontrolled human activities and using bioindicators could contribute some promising results. As such, this study tried to describe the Talabaan River in terms of the macroinvertebrate population, of which, could be used to assess the water quality condition of the River. Standard methods of specimen collection were done. Results showed that the water quality condition of the upstream until midstream portions of Talabaan River were relatively good, while relatively polluted water was observed at downstream, although it harboured all macroinvertebrate species.