Developing Joint Masters Programmes for Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuning Educational Structures in Europe

Cub 5 Tuning (20 mm) 3/7/08 10:58 Página 1 / Julia González & Robert Wagenaar (eds.) / Julia González & Robert Wagenaar Final Report Pilot Project - Phase 1 Carried out by over 100 Universities, coordinated by the University of Deusto (Spain) and the University of Groningen (The Netherlands) and supported by the European Commission uning Educational Structures in Europe uning Educational Structures T University of University of Education and Culture Deusto Groningen • • • • • • Socrates 0 Tuning Educational (Frutiger) 3/7/08 10:57 Página 3 Tuning Educational Structures in Europe 0 Tuning Educational (Frutiger) 3/7/08 10:57 Página 4 0 Tuning Educational (Frutiger) 3/7/08 10:57 Página 5 Tuning Educational Structures in Europe Final Report Phase One Edited by Julia González Robert Wagenaar 2003 University of University of Deusto Groningen The Tuning Project was supported by the European Commission in the Framework of the Socrates Programme. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the European Commission cannot be held responsi- ble for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. No part of this publication, including the cover design, may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by and means, whether electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, recording or photocopying, without prior permission of the publisher. Publication printed on ecological paper © Universidad de Deusto Apartado 1 - 48080 Bilbao ISBN: 978-84-9830-641-5 Design by: IPAR, S. Coop. - Bilbao 0 Tuning Educational (Frutiger) -

International Partners

BOSTON COLLEGE OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS International Partners Boston College maintains bilateral agreements for student exchanges with over fifty of the most prestigious universities worldwide. Each year the Office of International Programs welcomes more than 125 international exchange students from our partner institutions in approximately 30 countries. We are proud to have formal exchange agreements with the following universities: AFRICA Morocco Al Akhawayn University South Africa Rhodes University University of Cape Town ASIA Hong Kong Hong Kong University of Science and Techonology Japan Sophia University Waseda University Korea Sogang University Philippines Manila University AUSTRALIA Australia Monash University Murdoch University University of New South Wales University of Notre Dame University of Melbourne CENTRAL & SOUTH AMERICA Argentina Universidad Torcuato di Tella Universidad Catolica de Argentina Brazil Pontificia Universidad Católica - Rio Chile Pontificia Universidad Católica - Chile Universidad Alberto Hurtado Ecuador Universidad San Francisco de Quito HOVEY HOUSE, 140 COMMONWEALTH AVENUE, CHESTNUT HILL, MASSACHUSETTS 02467-3926 TEL: 617-552-3827 FAX: 617-552-0647 1 Mexico Iberoamericana EUROPE Bulgaria University of Veliko-Turnovo Denmark Copenhagen Business School University of Copenhagen G.B-England Lancaster University Royal Holloway University of Liverpool G.B-Scotland University of Glasgow France Institut Catholique de Paris Mission Interuniversitaire de Coordination des Echanges Franco-Americains – Paris -

University of Deusto

UNIVERSITY OF DEUSTO EMA Director Prof. Dr. Felipe Gómez Isa Websites: Fields of competence: Public International Law and International Human Rights Law www.deusto.es Other academics involved in EMA 2017/2018 www.idh.deusto.es Prof. Dr. Joana Abrisketa Uriarte Prof. Dr. Gorka Urrutia Department: Prof. Dr. Eduardo Ruiz Vieytez Prof. Dr. Trinidad L. Vicente Torrado Faculty of Social and Prof. Dr. Cristina Churruca Prof. Dr. Cristina de la Cruz Human Sciences Prof. Dr. Dolores Morondo The University and the city Contact persons: The University of Deusto was inaugurated in 1886. The concerns and cultural Prof. Felipe Gómez Isa interest of the Basque Country in having its own university, as well as the interest of EMA Director the Jesuits in establishing higher studies in some part of the Spanish State coincided Instituto de Derechos in its conception. Bilbao, a seaport and commercial city which was experiencing Humanos Pedro Arrupe considerable industrial growth during that era, was chosen as the ideal location. Universidad de Deusto Bilbao is the centre of a metropolitan area with more than one million inhabitants, Avda. de las a city traditionally open to Europe. It is, in addition, an important harbour, a Universidades 24, 48007 commercial and financial centre of the Basque Country and the north of Spain. In Bilbao September 1997, the city underwent a significant transformation under a symbol, Spain an emblematic building, the Bilbao Guggenheim Museum. The central headquarters Tel. +34 94 4139102 of the University of Deusto is situated on the opposite side of the estuary, facing the Email: Guggenheim Museum . [email protected] The University is located on two campuses, in the two coastal capitals of the Basque Country: Bilbao and San Sebastian. -

Global Partners —

EXCHANGE PROGRAM Global DESTINATION GROUPS Group A: USA/ASIA/CANADA Group B: EUROPE/UK/LATIN AMERICA partners Group U: UTRECHT NETWORK CONTACT US — Office of Global Student Mobility STUDENTS MUST CHOOSE THREE PREFERENCES FROM ONE GROUP ONLY. Student Central (Builing 17) W: uow.info/study-overseas GROUP B AND GROUP U HAVE THE SAME APPLICATION DEADLINE. E: [email protected] P: +61 2 4221 5400 INSTITUTION GROUP INSTITUTION GROUP INSTITUTION GROUP AUSTRIA CZECH REPUBLIC HONG KONG University of Graz Masaryk University City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong Baptist University DENMARK BELGIUM The Education University of Aarhus University Hong Kong University of Antwerp University of Copenhagen The Hong Kong Polytechnic KU Leuven University of Southern University BRAZIL Denmark UOW College Hong Kong Federal University of Santa ESTONIA HUNGARY Catarina University of Tartu Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas FINLAND ICELAND Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro University of Eastern Finland University of Iceland University of São Paulo FRANCE INDIA CANADA Audencia Business School Birla Institute of Management Technology (BIMTECH) Concordia University ESSCA School of Management IFIM Business School HEC Montreal Institut Polytechnique LaSalle Manipal Academy of Higher McMaster University Beauvais Education University of Alberta Lille Catholic University (IÉSEG School of Management) O.P. Jindal Global University University of British Columbia National Institute of Applied University of Calgary -

Welcome Guide

Deusto International Welcome guide Information for your stay at the University of Deusto international.deusto.es 3 Dear student, It is an honour for me to welcome you to the University of Deusto- a university that strives to blend contrasting features: our local roots and global challenges, knowledge from a historical perspective and concern for the future, leadership and social commitment, intellectual rigour and experience-based learning, competition and cooperation, tradition and innovation. Deusto will be your educational community for an important period of your life, and we trust that Deusto Educational Model, which was designed having students in mind, will help you develop your entrepeneurship and creative potential as you study, make key decisions, take part in teamwork and make commitments concerning your future and the persons around you. We aim to ensure that your Deusto experience is rewarding in every way, from relationships with classmates and lecturers to our administrative and services staff. We hope that you will find it fulfilling to be part of our diverse academic community, with people from over eighty countries. It will afford you a unique opportunity to broaden your horizons and explore your own ways of thinking, while learning how others see the world around us. We also hope that you make find friends and enjoy your stay in either Bilbao or San Sebastian. We have carefully prepared this Guide for you, to make sure your time at the University of Deusto will contribute to your success in the near future and will be fondly remembered in the future. We are pleased to offer you the assistance of our highly qualified staff who can provide you with the inspiration and help you require during your stay at our Institution. -

E-Proceedings

E-PROCEEDINGS Page 1/153 E-PROCEEDINGS INDEX Does Bank Screening Matter? Private Information and Public Securities Issues Edwin H. Neave - Queen's University School of Business .......................................................... 13 How do Price Limits Influence French Market Microstructure? A high Frequency Data Analysis in Terms of Return, Volatility and Volume Karine Michalon - Université Paris Dauphine ........................................................................... 14 Bailout Uncertainty in a Microfounded General Equilibrium Model of the Financial System Alex Cukierman - Interdisciplinary Center & Tel-Aviv University Yehuda Izhakian - New York University -Stern School of Business .......................................... 15 Is the World Heading towards Crisis-Induced Irrational Exuberance in International Assets? Investigating under Global Financial Stability APT Indranarain Ramlall - University of Mauritius ........................................................................ 16 Interest Rates and Credit Spread Dynamics Brice Dupoyet - Florida International University Xiaoquan Jiang - Florida International University Douglas Rolph - Nanyang Technological University Robert Neal - Indiana University .............................................................................................. 17 Explaining Hedge Fund Performance Fees Minli Lian - Kwantlen Polytechnic University Peter Klein - Simon Fraser University ...................................................................................... 18 FX Market -

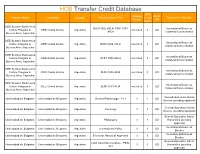

HCB Transfer Credit Database UTK Foreign LD Or Program Name Institution Country Foreign Course Title Credit Transfer Credit Type Credits UD Hours

HCB Transfer Credit Database UTK Foreign LD or Program Name Institution Country Foreign Course Title Credit Transfer Credit Type Credits UD Hours CIEE Summer Business & BUSI 3002 AFLA/ FINC 3001 International Business Culture Program in CIEE Global Insitute Argentina not listed 3 UD AFLA Collateral/Concentration Buenos Aires, Argentina CIEE Summer Business & International Business Culture Program in CIEE Global Insitute Argentina BUSI 3004 AFLA not listed 3 UD Collateral/Concentration Buenos Aires, Argentina CIEE Summer Business & International Business Culture Program in CIEE Global Insitute Argentina PLST 3002 AFLA not listed 3 UD Collateral/Concentration Buenos Aires, Argentina CIEE Summer Business & International Business Culture Program in CIEE Global Insitute Argentina BUSI 3004 AFIA not listed 3 UD Collateral/Concentration Buenos Aires, Argentina CIEE Summer Business & International Business Culture Program in CIEE Global Insitute Argentina BUSI 3003 AFIA not listed 3 UD Collateral/Concentration Buenos Aires, Argentina General Education Social Universidad de Belgrano Universidad de Belgrano Argentina General Psychology - 1-11 4 4 UD Science (pending apporval) General Education Social Universidad de Belgrano Universidad de Belgrano Argentina Sociology 3 3 UD Science (pending apporval) General Education Arts & Universidad de Belgrano Universidad de Belgrano Argentina Philosophy 3 3 UD Humanities (pending approval) International Business Universidad de Belgrano Universidad de Belgrano Argentina International Policy 3 3 UD Elective -

Bilbao, Spain, You Have a Bird's Eye View of This Elegant and Eclectic

Identity Cri sis rom Professor Eduardo Ruiz’S office in the University of Deusto in Bilbao, Spain, you have a bird’s eye view of this elegant and eclectic city’s center. Below, the Nervion River frames Frank Gehry’s mammoth wavy titanium mas- terwork, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Joggers and bikers amble and glide along separate running and bike paths. Well-fed business execu- tives in suits tuck in for long and decadent lunches with friends. Indeed, on a sunny day in May, the city recalls the hedonistic good feel of Los Angeles. This Basque city is a plainly cosmopoli- tan and wealthy, as is much of the Basque region of Spain. Viewing this sunny postcard, it is sometimes difficult for the casual visitor to imagine that a violent and vexing nationalist conflict, that between many Basques and the rest of Spain, persists. But it does. Around Bilbao, the green and wild Basque hills that are the domi- nant feature of the region’s topology encroach. Those hills hold a tiger in the tall grass. In June, ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, Basque for SEP.+OCT.07 r “Basque Homeland and Freedom”), the militant Basque nationalist movement, announced that it was formally ending its ceasefire that, with some exceptions, had helped cato staunch additions to ETA’s more than 800 killings in 40 years. Violence haunts the Spanish side, too, Edu with 700 ETA affiliated individuals in Spanish jails, deaths in Spanish prisons under questionable cir- ONAL i cumstances, and allegations of Spanish torture by human rights groups like Amnesty International. -

Legal Education Through Minority Languages Chapter Six

PART II LEGAL EDUCATION THROUGH MINORITY LANGUAGES CHAPTER SIX BASQUE-MEDIUM LEGAL EDUCATION IN THE BASQUE COUNTRY Xabier Arzoz A. Introduction In an area of 20,742 km2 and with a population of approximately three million, the Basque-speaking territories of Spain and France possess a high density of law schools. Legal education is off ered in the Basque- speaking territories through the medium of three languages: Spanish, French and Basque. However, most of the law schools follow single- medium education. French is the medium of instruction at the multi- disciplinary Faculty of Bayonne (France) which teaches law and forms part of the Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour, and Spanish is the medium of instruction at the law schools of the two Universities of Navarre (the Public University of Navarre and the private, Opus Dei- owned University of Navarre) and at the Spanish Distance Univer- sity (UNED), which has premises in Portugalete and Bergara. Legal education is only bilingual (Spanish-Basque) at the law schools of the public University of the Basque Country and of the private, Jesuit- owned University of Deusto. Th ere is a third private University, Mondragon University, that is highly committed to Basque-medium education but it does not include a law school. It is not casual that both the University of the Basque Country and the University of Deusto have the only bilingual law schools. Th ey are located in the Basque autonomous community, which, on the one hand, with 2.1 million inhabitants, is the most populated Basque terri- tory and, on the other hand, constitutes a region (or ‘autonomous community’ in the terms of Spanish constitutional law) that has used the devolution of power from 1978 onwards to advance the legal status and the social use of the Basque language. -

(E.MA JOINT PROGRAMME) Preamble Considering Th

AGREEMENT ON THE EUROPEAN MASTER’S DEGREE IN HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATISATION (E.MA JOINT PROGRAMME) Preamble Considering that human rights and democracy are fundamental values for all human beings and societies; Considering that the European Union, as stated in article 6 of the Treaty on European Union, is founded on the principles of liberty, democracy, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and the rule of law, and that it promotes respect for human rights, according to the principles of universality, interdependence and indivisibility of all human rights, rights, as well as considering the adoption and entry into force of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights; Considering the necessity of developing the teaching of human rights and democracy in the universities, as well as in the overall teaching systems both in school and out of school, in co-operation with national, European and international organisations and civil society entities; Fully aware of the importance of the university in promoting a law-based civilisation, at the national, European, and international levels, infused with the universal human values, as proclaimed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and all relevant international and regional instruments; Bearing in mind the spirit of the Sorbonne Declaration of 25 May 1998 on “Harmonizing the Architecture of Higher Education Systems in Europe”, and of the Bologna Declaration of 19 June 1999 on the “European Space for Higher Education”, that emphasize the importance of a “Europe of Knowledge” -

Msca- Cofund Programme

MSCA- COFUND PROGRAMME OPENING UP NEW HORIZONS FOR RESEARCHERS ONGOING COFUND PROGRAMMES IN SPAIN: EXPECTED CALLS FOR THE RECRUITMENT OF RESEARCHERS (2019-2020) MSCA-COFUND PROGRAMME: OPENING UP NEW HORIZONS FOR RESEARCHERS ONGOING COFUND PROGRAMMES IN SPAIN: EXPECTED CALLS FOR THE RECRUITMENT OF RESEARCHERS This document compiles information relative to those ongoing MSCA-COFUND PROGRAMMES in Spain with foreseen open calls in 2019 and 2020 for the recruitment of researchers. Further information about other opportunities for researchers in Spain can be found at EURAXESS SPAIN under section “Science in Spain”: https://www.euraxess.es. September 2019 Edited: FECYT Design and layout: FECYT e-NIPO: 69219017X Table of contents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 MSCA COFUND ONGOING PROGRAMMES IN SPAIN 2019-2020 Expected calls for early stage researchers 6i-DIRS: A growing attractive collaborative ecosystem for boosting impact driven research careers (University of Deusto) .............................................. 8 ENLIGHTEN, ENhanced PhD Fellowship Programme in the Sciences of LIGHT (ICFO) ...................................................................................................... 10 IberusTalent, International Doctoral Programme for Talent Attraction to the Campus of International Excellence of the Ebro Valley ....................... 12 Expected calls for experienced researchers BP3, Beatriu de Pinos-3 Postdoctoral Programme ..................................... -

Bilbao, Spain

2013 Remaking Cities Congress Re-Positioning the Post-Industrial City in the Global Economy Case Study Summary Bilbao, Spain Juan Alayo Bilbao Ria 2000 October 3, 2013 Over the last 30 years, Bilbao has evolved from a city with severe environmental problems and a structurally run-down industrial system to being one of the most attractive cities in Europe to live in, visit and invest in. Bilbao has undergone a remarkable and recognized transformation, living out a dream which has put the city at the international forefront of urban transformation, but along with this physical transformation we have to also highlight its economic and knowledge transformation. Founded in the year 1300 as a medieval villa or town, Bilbao became in 1511, when the trade and shipping office or Consulado was created, a trade outlet and subsequently, at the end of the 19th century, it was transformed into an industrial city covering its entire metropolitan area. The industrial stage experienced a major crisis between late 70s and early 80s and facing a need for change, the City lived a physical change undergoing a resetting in the economic scheme, in early 80s Basque Country’s economy structure accounted 48% Industry sector and 36% Service Sector, between 1983 and 2008 this became 62% Services and 27% Industry and after the Urban transformation Bilbao has been focusing its economy in Creativity, New Technologies, Innovation moving forward to Knowledge economy. Reopening citizenship to a new attitude towards the global sphere was also a hard task for authorities but the City’s success restored their faith in the future of Bilbao, lost during the harsh years of economic crisis.