Teaching Food Studies in Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chimichanga Carne Asada Pollo Salad Fajita Texana Appetizers Chicken Wings Cheese Dip – 3.25 Chicken Wings Served with Celery and Ranch Dressing

Chimichanga Carne Asada Pollo Salad Fajita Texana Appetizers Chicken Wings Cheese Dip – 3.25 Chicken Wings Served with celery and ranch dressing. Bean Dip Choice of plain, hot and BBQ. Refried beans smothered with (10) – 8.50 our cheese sauce – 3.75 Jalisco Sampler Chorizo Dip Beef taquitos, grilled chicken Mexican sausage smothered with quesadillas and 4 wings – 8.75 our cheese sauce – 4.25 Triangle Quesadillas Guacamole Dip – 3.25 Grilled chicken or steak quesadilla Chunky Guacamole Dip with guacamole, pico de gallo, sour Our chunky guacamole made with diced cream and lettuce – 7.00 avocado, onions, tomatoes and cilantro – 4.50 Jalisco’s Spinach Dip Loaded Cheese Fries Chopped baby spinach smothered French fries covered with Monterey cheese, with our cheese sauce – 4.50 cheddar cheese and our own cheese Jalisco Dip sauce, bacon bits and jalapeños – 5.50 Triangle Quesadillas Ground beef smothered in cheese sauce – 3.50 Jalapeño Poppers (6) Pico de Gallo Filled with cream cheese – 4.55 Tomatoes, onions and cilantro mixed Mozzarella Sticks (6) – 4.55 together with squeezed lime juice and a pinch of salt – 1.75 Nachos Served anytime. All nachos include cheese. Fajita Nachos Nachos with Beef & Beans – 6.25 Nachos topped with chicken or steak strips cooked with grilled onions and bell peppers – 8.75 Nachos con Pollo Nachos with chicken and melted cheese – 6.25 Nachos Supreme Nachos topped with beef or chicken, lettuce, Fiesta tomato, sour cream and grated cheese – 6.75 Nachos topped with chicken, cheese, ground beef, beans, lettuce, guacamole, -

Chicken POLLO Vegetarian 999 Chimichangas

chicken POLLO | CHIMICHANGAS | CHICKEN STEAKS | VEGETARIAN | SPECIALTIES All dishes come with tortillas POLLO FAVORITO POLLO AZADO Grilled chicken breast with tropical Grilled chicken breast served with vegetables and a salad 12.99 a salad and avocado 12.50 POLLO FUNDIDO ARROZ CON POLLO Shredded chicken over rice with chorizo Chicken strips over a bed of rice, covered in our and cheese. Served with tortillas 12.99 cheese sauce and served with tortillas 13.99 POLLO LOCO ARROZ CON POLLO Y CAMARONES Grilled chicken breast with shrimp and Chicken strips and shrimp tossed with onion. Served with a salad and rice 14.50 cheese dip. Served with Mexican rice 14.50 HOT & SPICY CHICKEN NEW! POLLO JALISCO Chicken strips in a spicy Diabla sauce with Grilled chicken strips with mushrooms and spinach. onion. Served with rice and beans 13.50 Served with rice, beans, cheese and tortillas 13.50 POLLO TROPICAL NEW! POLLO CHIPOTLE Chicken breast with a tropical veggie mix Grilled chicken strips covered in our delicious chipotle and pineapple. Served with rice 13.50 sauce. Served with rice, beans and tortillas 13.50 NEW! POLLO HAWAIIANO NEW! ARROZ CON POLLO AND VEGGIES Grilled chicken breast cooked with onions, ham Grilled chicken strips and California veggies. Topped and pineapple, then topped with cheese. Served with cheese dip, Served on a bed of rice 12.99 with rice, beans and flour tortillas 13.50 NEW! POLLO MONTERREY Grilled chicken breast, onions, mushrooms, tomatoes and peppers, topped with cheese. Served with rice and beans 13.50 NEW! POLLO TOLUCA Grilled chicken breast with chorizo and cheese. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Botanas (Appetizers)

Salsa Macha GF Botanas (Appetizers) chile de arbol and garlic roasted to a nutty, spicy, crumbly salsa, served with queso Cochinita Pibil GF fresco, avocado and mini tortillas (spice up any entrée!) marinated pork in an achiote recipe, slowly roasted until tender, served wrapped in Shrimp Jalapeño Poppers three lightly seared mini tortillas, topped with seasoned marinated onions and mexican three tiger prawn shrimp stuffed with a hint of our house blend cheese, wrapped in crema 9 bacon, grilled jalapeño fried in beer batter, served with our chipotle cream sauce 15 Quesadilla Mini Empanaditas GF flour or corn masa tortillas with melted house blend oaxaca cheese, served with melted house blend oaxaca cheese with a jalapeño slice, or shrimp and chorizo topped guacamole, pico de gallo and sour cream 11 with crema and queso cotija, three empanaditas 9, six empanaditas 18 Add Shredded Chicken, Shredded Beef, Grilled Chicken, Carnitas, Chicken Tinga, Carne Asada, Sautéed Veggies or Shrimp 2 Guacamole GF avocado, tomatoes, onions, cilantro, jalapeños and fresh limes, topped with queso Quesadilla de Chipotle GF fresco and crispy tortillas 11 / 18 fresh corn masa with chipotle, filled with melted house blend oaxaca cheese, stuffed Add Shrimp or Crab Seared in Abuelo Spicy Sauce 2 with choice of sautéed veggies or black beans, served with pico de gallo, guacamole and sour cream 10 Queso Fundido GF Sopas y Ensaladas mexican blend of traditional oaxaca cheese melted in a cast iron pan, served with Sopa de Fideo choice of flour or corn mini tortillas -

Footscrayfood Guide Lauren Wambach Picks from the Footscray Food Blogger Getting to Footscray

Australia. cuisine. each end of Vietnam on offer. offer. on Vietnam of end each occasional wayward seal. wayward occasional quality and freshness. and quality or spiced potato (right). potato spiced or Maribyrnong River attracts birdlife and even the the even and birdlife attracts River Maribyrnong authentic cuisines you will find in in find will you cuisines authentic to introduce you to this unique unique this to you introduce to pho, and traditional dishes from from dishes traditional and pho, Footscray food scene a consistently high standard in in standard high consistently a scene food Footscray brown lentil, chickpea, carrot carrot chickpea, lentil, brown an important inner city conservation park. The The park. conservation city inner important an produce centre, Little Saigon Market, giving the the giving Market, Saigon Little centre, produce silverbeet, cabbage, red lentil, lentil, red cabbage, silverbeet, and Newells Paddock Wetland Reserve is considered considered is Reserve Wetland Paddock Newells and offers up some of the most most the of some up offers of restaurants in the country ready ready country the in restaurants of style food, iced coffee, pork rolls, rolls, pork coffee, iced food, style wholesale fish market or specialty Vietnamese Vietnamese specialty or market fish wholesale a sampling of stews with with stews of sampling a Park is one of the largest Edwardian parks in Australia Australia in parks Edwardian largest the of one is Park sourced direct from the local Footscray Market, Market, Footscray local the from direct sourced Vegetarian combination: combination: Vegetarian from the homeland, Footscray Footscray homeland, the from hosting the highest concentration concentration highest the hosting street from everything There is natural beauty too. -

Luxury Culinary Tours Vietnam: 28Th February – 7Th March 2018 8 DAYS / 7 NIGHTS

Luxury Culinary Tours Vietnam: 28th February – 7th March 2018 8 DAYS / 7 NIGHTS Authentic Flavour Filled Food Adventure FULLY ESCORTED FROM HO CHI MINH CITY TO HANOI BY TANIA SIBREY FROM FOOD I AM & A NATIONAL TOUR ESCORT IN VIETNAM Wednesday 28th February 2018: Ho Chi Minh City Day 1 In the city formerly known as Saigon, Art Deco treasures, magnificent French colonial buildings and traditional Chinese temples abound. Upon independent arrival to HCMC check into your Luxury hotel. Meet Tania (Food I Am) 6.30pm at the hotel rooftop bar and watch over the city lights of Ho Chi Minh City. Your culinary journey through Vietnam begins! Dinner tonight will be at a destination for gourmet food lovers. It won’t take you long to discover the diversity of Vietnamese cuisine! The subtle flavours of the food highlight the three regions of Vietnam. From the gentle flavour of the steamed rice rolls stuffed with pork and mushroom, hot rice flour cake with ground pork or the profound flavour of fresh water crab noodle soup to the noodle soup with steamed snail!! All leave a strong impression for the gourmet food lover. Meals: Dinner Accommodation: Luxury Accommodation Food I Am Luxury Culinary Vietnam Tour - Feb/Mar 2018 For bookings or further information, phone Tania on 0427 250 498 Thursday 1st Friday 2nd March 2018: March 2018: Ho Chi Minh City to Mekong Delta to Mekong Delta Hoi An Day 2 Day 3 After buffet breakfast at the hotel we will depart bustling Breakfast on the Mekong is something you will Ho Chi Minh City for the Mekong. -

Hi on 55 Menus.Cdr

55 High Street, West on Fremantle WA Menus Ph: 9336 2604 M O R N I N G 7am to 10:30am sleep is a time machine to breakfast! 2 EGGS ON TOAST-poached, fried or scrambled 9.5 TOASTED BACON & EGG SANDWICH 8.5 B.E.L.T SANDWICH-bacon, egg, lettuce. tomato 9.5 THICK CUT FRUIT TOAST-served with butter 6.5 2 SLICES OF TOAST-served with butter, jam or honey or vegemite 5.5 MARINATED MUSHROOMS, FETA & TOAST 11.5 BAKED BEANS ON TOAST 7.0 KIDS BREAKFAST-1 slice bacon, hash brown, beans, toast 8.5 TOASTED MUESLI-served with fruit, yogurt & milk 8.5 BIG BREAKIE-eggs, bacon, hashbrown, tomato, mushrooms, toast 19.5 make it that little bit extra? BACON 3.5 BAKED BEANS 4.0 EXTRA EGG 3.0 SMOKED SALMON 4.5 GRILLED TOMATO 3.0 BABY SPINACH 2.0 FRESH AVOCADO 3.0 GLUTEN FREE TOAST 2.0 HASH BROWN 2.0 N O O N 10:30am to 2:30pm happiness is a good lunch! PHO BO–noodle soup with beef & rice stick noodles 14.5 PHO GA–noodle soup with chicken & rice stick noodles 14.5 PENANG LAKSA-coconut curry soup as chicken or vegetarian 14.5 served with yellow wheat noodle or rice vermicelli Seafood 16.0 CANH CHUA-traditional vegtarian or chicken spicy sour soup 14.5 with rice vermicelli Seafood 16.0 BUN BO HUE-spicy noodle soup with beef, pork & rice vermicelli 14.5 BUN BI THIT NUONG-grilled marinated pork chop & rice vermicelli 14.5 BUN BO XAO-braised lemongrass beef with rice vermicelli 14.5 BUN GA XAO-marinated wok cooked chicken with rice vermicelli 14.5 BUN BI CHA GIO-meat spring rolls with pork & rice vermicelli 14.5 BUN CHA GIO CHAY-vegetarian spring rolls with rice vermicelli -

The W Orld's Bes T Bowl Fo Od

the world’s best bowl food bowl best the world’s Discover 100 one-pot recipes from all over the globe that’ll set you up for the day, warm the core or humbly feed friends and family. From sizzling bibimbap soul food in Korea to spiced Algerian chicken soup, explore the culture and cooking methods behind the planet’s most comforting dishes. Authentic recipes from around the world Contents FOReWoRD 6 Pozole Mexico 56 Samgyetang Korea 58 BREAKFAST BOWLS 8 Sopa do Espirito Santo Chia pudding Central Portugal 60 and South America 10 Tom yam gung Thailand 62 Congee China 12 Fèves au lard Canada 14 SALADS & Frumenty England 16 HEALTHY BOWLS 64 Ful medames Egypt 18 Bibimbap Korea 66 Museli Europe, USA, Burrito bowl USA 68 Australia and UK 20 Caesar salad Mexico 70 Porridge Ireland 22 Ceviche Peru 72 Zucchini and fig smoothie bowl Chinese chicken salad USA 74 Tempeh with spicy kale Macaroni and cheese USA 132 Boeuf bourguignon France 160 Sancocho de gallina Panama 196 USA 24 Chirashi sushi Japan 76 and black quinoa USA 104 Manti Turkey 134 Bunny chow South Africa 162 Stovies Scotland 198 Cobb salad USA 78 Waldorf salad USA 106 Mohinga Myanmar (Burma) 136 Cassoulet France 164 Tomato bredie South Africa 200 SOUPS 26 Fattoush Lebanon and Syria 80 Wild rice and sweet potato Nasi goreng Indonesia 138 Charquican Chile 166 Welsh cawl Wales 202 Ajiaco Colombia 28 Horiatiki Greece 82 power bowl USA 108 Oyako donburi Japan 140 Chilli con carne USA 168 Avgolemono Greece 30 Jewelled couscous Pat thai Thailand 142 Colcannon Ireland 170 DESSERTS 204 Borscht -

Galangal and Chilies That Are Pounded Together Into a Paste

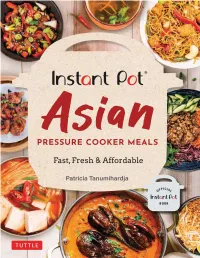

Instant Pot® Asian PRESSURE COOKER MEALS Fast, Fresh & Affordable Patricia Tanumihardja Contents Getting the Most from Your Instant Pot® About Your Instant Pot® Instant Pot® Accessories Useful Tips My Asian Pantry Staples THE BASICS Cooking Rice in an Instant Pot® Making Asian-Style Chicken Stock Making Japanese-Style Dashi Fish Stock SOUPS, STARTERS & SIDES Homemade Wonton Soup Japanese-Style Soy Sauce Eggs Seasoned Bamboo Shoots Pickled Chinese Mustard Cabbage Quick Cucumber Kimchi Japanese Savory Egg Custard Thai Chicken Coconut Soup VEGETABLES & MEATLESS MAINS Tips for Cooking Instant Pot Vegetables Panang Vegetable Curry with Tofu Lohan Mixed Vegetables Spiced Cauliflower and Potatoes Curried Lentils with Dates & Caramelized Onions Spicy Chickpeas in Tomato Sauce Kimchi Tofu Stew Baby Eggplant Curry ONE-DISH MEALS FOR A CROWD Indian Chicken Biryani Rice Vietnamese Chicken Noodle Soup Hainanese Chicken Rice Vietnamese Meatballs with Rice Noodles Thai Red Curry Chicken Noodles Fragrant Oxtail Stew Japanese Shoyu Ramen Noodles Taiwanese Spicy Beef Noodles Korean Bibimbap Mixed Rice Bowl NOODLES & RICE Korean Glass Noodles Chicken Lo Mein Thai Basil Chicken Rice Filipino Pancit Canton Noodles with Pork Pad Thai Filipino-Style Spaghetti Fried Rice “Risotto” Vietnamese Garlic Butter Noodles BEEF DISHES Japanese-Style Beef and Potato Stew Braised Korean Short Ribs Tangy Filipino Beefsteak Beef with Broccoli CHICKEN DISHES Lemon Teriyaki Glazed Chicken Orange Chicken Chicken and Egg Rice Bowls Chicken Adobo Chicken Rendang Curry Yellow Chicken -

View of ASEAN Food William W

Foreword Amb. Kim Young-sun Secretary General, ASEAN-Korea Centre The ASEAN* region has a great variety of cuisines that are distinctive despite having some common elements. ASEAN cuisine is a celebration of cultural diversity and unique ways of life, delivered through appetite-whetting dishes and exotic aromas. It embraces the unique characteristics of many different ethnicities, and in that way is a history of the culture of the region. The ASEAN spirit and passion permeate each and every dish, and food is an important link in the chain that binds the ASEAN community together. The ASEAN Culinary Festival 2016, organized by the ASEAN-Korea Centre, aims to introduce ASEAN cuisine to the Korean public by presenting a wide spectrum of ASEAN dishes. Thirty distinctive dishes are included; they were selected to suit the Korean palate while showcasing the diverse flavors of ASEAN. Under the theme “Gourmet Trips to ASEAN,” the Festival will help Koreans, also known for their cuisine, discover the sweet and savory ASEAN culinary delights. In line with the “Visit ASEAN@50: Golden Celebration” campaign to celebrate the 50th anniversary of ASEAN, the Festival also intends to promote ASEAN culinary destinations by showcasing fascinating food trails across the region to the Korean public. Food is a universal language that brings people and cultures together. It is an essential part of life to all people of all nations. With the rise in the number of tourists traveling specifically to experience the cuisine of other peoples, food is increasingly important in enhancing harmony around the world. In this regard, I am certain that the ASEAN Culinary Festival will serve as a platform to strengthen the partnership between ASEAN and Korea by connecting the hearts and minds of the people and creating a bond over a “shared meal of diversity.” With the ASEAN-Korea Cultural Exchange Year in 2017, the ASEAN Culinary Festival is a new way to bring deeper cultural understanding between ASEAN and Korea. -

Enchilada Loca RECIPES

Enchilada Loca RECIPES 24 96 INGREDIENTS SERVINGS SERVINGS 1 Serving = 2 Rolls 1 Serving = 2 Rolls El Monterey® Chicken & Cheese 48 Taquitos 192 Taquitos Taquitos 40818 Enchilada Sauce 7 cups 1.75 gallons Vegetable Oil 6 Tbsp 1.5 cups Flour, All Purpose 6 Tbsp (17 gm) 1.5 cups (2.4 oz) Chili Powder 6 Tbsp 1.5 cups Coriander 2 tsp 2 2/3 Tbsp Cumin 1 tsp 1 1/3 Tbsp Cinnamon 1/16 tsp 1/4 tsp Granulated Garlic 1 tsp 1 1/3 Tbsp Cocoa Powder 1 tsp (1.6 gm) 1 1/3 Tbsp (6.4 gm) NUTRIENTS PER SERVING Chicken Stock 4 cups 1 gallon Calories: 292 Saturated Fat (g): 3 Water 1 cup 1 qt Sodium (mg): 878 Kcal from Sat.: 9% Tomato Paste 1 cup 1 qt Total Fat (g): 12 Carbohydrate (g): 32 Cheddar-Mozzarella 12 oz 3 lb Kcal from Fat: 37% Sugars (g): 3 Mix Allergens: Milk, gluten, wheat, soy DIRECTIONS PREPARE THE INGREDIENTS: Collect all ingredients, ASSEMBLY: Spray a 2-inch full pan, bottom and sides. Pour a half cup of sauce measured by volume or weight as indicated. One and tilt pan to spread as evenly as possible. Place 24 rolls into the 2-inch full pan 2-inch hotel pan per 12 servings is needed. 8 wide and 3 long. Pour one cup of sauce over each row of 8 rolls, covering the ends. Cover tightly and bake at 350°F for 10-14 minutes. PREPARE THE SAUCE*: Add oil and our to stock pot and cook on medium-high heat while stirring until GARNISH: Remove cover and sprinkle with 3/4 lb of cheese per pan. -

List of Asian Cuisines

List of Asian cuisines PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 26 Mar 2014 23:07:10 UTC Contents Articles Asian cuisine 1 List of Asian cuisines 7 References Article Sources and Contributors 21 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 22 Article Licenses License 25 Asian cuisine 1 Asian cuisine Asian cuisine styles can be broken down into several tiny regional styles that have rooted the peoples and cultures of those regions. The major types can be roughly defined as: East Asian with its origins in Imperial China and now encompassing modern Japan and the Korean peninsula; Southeast Asian which encompasses Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines; South Asian states that are made up of India, Burma, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan as well as several other countries in this region of the Vietnamese meal, in Asian culture food often serves as the centerpiece of social continent; Central Asian and Middle gatherings Eastern. Terminology "Asian cuisine" most often refers to East Asian cuisine (Chinese, Japanese, and Korean), Southeast Asian cuisine and South Asian cuisine. In much of Asia, the term does not include the area's native cuisines. For example, in Hong Kong and mainland China, Asian cuisine is a general umbrella term for Japanese cuisine, Korean cuisine, Filipino cuisine, Thai cuisine, Vietnamese cuisine, Malaysian and Singaporean cuisine, and Indonesian cuisine; but Chinese cuisine and Indian cuisine are excluded. The term Asian cuisine might also be used to Indonesian cuisine address the eating establishments that offer a wide array of Asian dishes without rigid cuisine boundaries; such as selling satay, gyoza or lumpia for an appetizer, som tam, rojak or gado-gado for salad, offering chicken teriyaki, nasi goreng or beef rendang as the main course, tom yam and laksa as soup, and cendol or ogura ice for dessert.