High Dynamic Range Imaging by Perceptual Logarithmic Exposure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logarithmic Image Sensor for Wide Dynamic Range Stereo Vision System

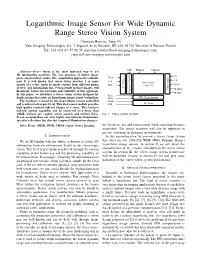

Logarithmic Image Sensor For Wide Dynamic Range Stereo Vision System Christian Bouvier, Yang Ni New Imaging Technologies SA, 1 Impasse de la Noisette, BP 426, 91370 Verrieres le Buisson France Tel: +33 (0)1 64 47 88 58 [email protected], [email protected] NEG PIXbias COLbias Abstract—Stereo vision is the most universal way to get 3D information passively. The fast progress of digital image G1 processing hardware makes this computation approach realizable Vsync G2 Vck now. It is well known that stereo vision matches 2 or more Control Amp Pixel Array - Scan Offset images of a scene, taken by image sensors from different points RST - 1280x720 of view. Any information loss, even partially in those images, will V Video Out1 drastically reduce the precision and reliability of this approach. Exposure Out2 In this paper, we introduce a stereo vision system designed for RD1 depth sensing that relies on logarithmic image sensor technology. RD2 FPN Compensation The hardware is based on dual logarithmic sensors controlled Hsync and synchronized at pixel level. This dual sensor module provides Hck H - Scan high quality contrast indexed images of a scene. This contrast indexed sensing capability can be conserved over more than 140dB without any explicit sensor control and without delay. Fig. 1. Sensor general structure. It can accommodate not only highly non-uniform illumination, specular reflections but also fast temporal illumination changes. Index Terms—HDR, WDR, CMOS sensor, Stereo Imaging. the details are lost and consequently depth extraction becomes impossible. The sensor reactivity will also be important to prevent saturation in changing environments. -

Receiver Dynamic Range: Part 2

The Communications Edge™ Tech-note Author: Robert E. Watson Receiver Dynamic Range: Part 2 Part 1 of this article reviews receiver mea- the receiver can process acceptably. In sim- NF is the receiver noise figure in dB surements which, taken as a group, describe plest terms, it is the difference in dB This dynamic range definition has the receiver dynamic range. Part 2 introduces between the inband 1-dB compression point advantage of being relatively easy to measure comprehensive measurements that attempt and the minimum-receivable signal level. without ambiguity but, unfortunately, it to characterize a receiver’s dynamic range as The compression point is obvious enough; assumes that the receiver has only a single a single number. however, the minimum-receivable signal signal at its input and that the signal is must be identified. desired. For deep-space receivers, this may be COMPREHENSIVE MEASURE- a reasonable assumption, but the terrestrial MENTS There are a number of candidates for mini- mum-receivable signal level, including: sphere is not usually so benign. For specifi- The following receiver measurements and “minimum-discernable signal” (MDS), tan- cation of general-purpose receivers, some specifications attempt to define overall gential sensitivity, 10-dB SNR, and receiver interfering signals must be assumed, and this receiver dynamic range as a single number noise floor. Both MDS and tangential sensi- is what the other definitions of receiver which can be used both to predict overall tivity are based on subjective judgments of dynamic range do. receiver performance and as a figure of merit signal strength, which differ significantly to compare competing receivers. -

For the Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products (Ba5105)

Technical Documentation Microphone Handbook For the Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products Brüel&Kjær B K WORLD HEADQUARTERS: DK-2850 Nærum • Denmark • Telephone: +4542800500 •Telex: 37316 bruka dk • Fax: +4542801405 • e-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.bk.dk BA 5105 –12 Microphone Handbook Revision February 1995 Brüel & Kjær Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products BA 5105 –12 Microphone Handbook Trademarks Microsoft is a registered trademark and Windows is a trademark of Microsoft Cor- poration. Copyright © 1994, 1995, Brüel & Kjær A/S All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without prior consent in writing from Brüel & Kjær A/S, Nærum, Denmark. 0 − 2 Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products Brüel & Kjær Microphone Handbook Contents 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 – 1 1.1 About the Microphone Handbook............................................................................... 1 – 2 1.2 About the Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products.................................................. 1 – 2 1.3 The Microphones ......................................................................................................... 1 – 2 1.4 The Preamplifiers........................................................................................................ 1 – 8 1 2. Prepolarized Free-field /2" Microphone Type 4188....................... 2 – 1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ -

Signal-To-Noise Ratio and Dynamic Range Definitions

Signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range definitions The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and Dynamic Range (DR) are two common parameters used to specify the electrical performance of a spectrometer. This technical note will describe how they are defined and how to measure and calculate them. Figure 1: Definitions of SNR and SR. The signal out of the spectrometer is a digital signal between 0 and 2N-1, where N is the number of bits in the Analogue-to-Digital (A/D) converter on the electronics. Typical numbers for N range from 10 to 16 leading to maximum signal level between 1,023 and 65,535 counts. The Noise is the stochastic variation of the signal around a mean value. In Figure 1 we have shown a spectrum with a single peak in wavelength and time. As indicated on the figure the peak signal level will fluctuate a small amount around the mean value due to the noise of the electronics. Noise is measured by the Root-Mean-Squared (RMS) value of the fluctuations over time. The SNR is defined as the average over time of the peak signal divided by the RMS noise of the peak signal over the same time. In order to get an accurate result for the SNR it is generally required to measure over 25 -50 time samples of the spectrum. It is very important that your input to the spectrometer is constant during SNR measurements. Otherwise, you will be measuring other things like drift of you lamp power or time dependent signal levels from your sample. -

High Dynamic Range Ultrasound Imaging

The final publication is available at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11548-018-1729-3 Int J CARS manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) High Dynamic Range Ultrasound Imaging Alperen Degirmenci · Douglas P. Perrin · Robert D. Howe Received: 26 January 2018 Abstract Purpose High dynamic range (HDR) imaging is a popular computational photography technique that has found its way into every modern smartphone and camera. In HDR imaging, images acquired at different exposures are combined to increase the luminance range of the final image, thereby extending the limited dynamic range of the camera. Ultrasound imaging suffers from limited dynamic range as well; at higher power levels, the hyperechogenic tissue is overexposed, whereas at lower power levels, hypoechogenic tissue details are not visible. In this work, we apply HDR techniques to ultrasound imaging, where we combine ultrasound images acquired at different power levels to improve the level of detail visible in the final image. Methods Ultrasound images of ex vivo and in vivo tissue are acquired at different acoustic power levels and then combined to generate HDR ultrasound (HDR-US) images. The performance of five tone mapping operators is quantitatively evaluated using a similarity metric to determine the most suitable mapping for HDR-US imaging. Results The ex vivo and in vivo results demonstrated that HDR-US imaging enables visualizing both hyper- and hypoechogenic tissue at once in a single image. The Durand tone mapping operator preserved the most amount of detail across the dynamic range. Conclusions Our results strongly suggest that HDR-US imaging can improve the utility of ultrasound in image-based diagnosis and procedure guidance. -

Preview Only

AES-6id-2006 (r2011) AES information document for digital audio - Personal computer audio quality measurements Published by Audio Engineering Society, Inc. Copyright © 2006 by the Audio Engineering Society Preview only Abstract This document focuses on the measurement of audio quality specifications in a PC environment. Each specification listed has a definition and an example measurement technique. Also included is a detailed description of example test setups to measure each specification. An AES standard implies a consensus of those directly and materially affected by its scope and provisions and is intended as a guide to aid the manufacturer, the consumer, and the general public. An AES information document is a form of standard containing a summary of scientific and technical information; originated by a technically competent writing group; important to the preparation and justification of an AES standard or to the understanding and application of such information to a specific technical subject. An AES information document implies the same consensus as an AES standard. However, dissenting comments may be published with the document. The existence of an AES standard or AES information document does not in any respect preclude anyone, whether or not he or she has approved the document, from manufacturing, marketing, purchasing, or using products, processes, or procedures not conforming to the standard. Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this AES standard or information document may be the subject of patent rights. AES shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patents. This document is subject to periodicwww.aes.org/standards review and users are cautioned to obtain the latest edition and printing. -

Understanding Microphone Sensitivity by Jerad Lewis

Understanding Microphone Sensitivity By Jerad Lewis Sensitivity, the ratio of the analog output voltage or digital output value to the input pressure, is a key specification of any microphone. Mapping units in the acoustic domain to units in the electrical domain, it determines the magnitude of the microphone output signal given a known input. This article will discuss the distinction in sensitivity specifications between analog and digital microphones, how to choose a microphone with the best sensitivity for the application, and why adding a bit (or more) of digital gain can enhance the microphone signal. Analog vs. Digital Microphone sensitivity is typically measured with a 1 kHz sine wave at a 94 dB sound pressure level (SPL), or 1 pascal (Pa) pressure. The magnitude of the analog or digital output signal from the microphone with that input stimulus is a measure of its sensitivity. This reference point is but one characteristic of the microphone, by no means the whole story of its performance. The sensitivity of an analog microphone is straightforward and easy to understand. Typically specified in logarithmic units of dBV (decibels with respect to 1 V), it tells how many volts the output signal will be for a given SPL. For an analog microphone, sensitivity, in linear units of mV/Pa, can be expressed logarithmically in decibels: Sensitivity = × mV / Pa Sensitivity dBV 20 log10 Output REF where OutputREF is the 1000 mV/Pa (1 V/Pa) reference output ratio. Given this information, with the appropriate preamplifier gain, the microphone signal level can be easily matched to the desired input level of the rest of the circuit or system. -

A History of Audio Effects

applied sciences Review A History of Audio Effects Thomas Wilmering 1,∗ , David Moffat 2 , Alessia Milo 1 and Mark B. Sandler 1 1 Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London, London E1 4NS, UK; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (M.B.S.) 2 Interdisciplinary Centre for Computer Music Research, University of Plymouth, Plymouth PL4 8AA, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 December 2019; Accepted: 13 January 2020; Published: 22 January 2020 Abstract: Audio effects are an essential tool that the field of music production relies upon. The ability to intentionally manipulate and modify a piece of sound has opened up considerable opportunities for music making. The evolution of technology has often driven new audio tools and effects, from early architectural acoustics through electromechanical and electronic devices to the digitisation of music production studios. Throughout time, music has constantly borrowed ideas and technological advancements from all other fields and contributed back to the innovative technology. This is defined as transsectorial innovation and fundamentally underpins the technological developments of audio effects. The development and evolution of audio effect technology is discussed, highlighting major technical breakthroughs and the impact of available audio effects. Keywords: audio effects; history; transsectorial innovation; technology; audio processing; music production 1. Introduction In this article, we describe the history of audio effects with regards to musical composition (music performance and production). We define audio effects as the controlled transformation of a sound typically based on some control parameters. As such, the term sound transformation can be considered synonymous with audio effect. -

Fast Multiplierless Approximations of the DCT with the Lifting Scheme Jie Liang, Student Member, IEEE, and Trac D

3032 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SIGNAL PROCESSING, VOL. 49, NO. 12, DECEMBER 2001 Fast Multiplierless Approximations of the DCT With the Lifting Scheme Jie Liang, Student Member, IEEE, and Trac D. Tran, Member, IEEE Abstract—In this paper, we present the design, implementation, the sparse factorizations of the DCT matrix [12]–[17], and and application of several families of fast multiplierless approx- many of them are recursive [12], [14], [16], [17]. Besides imations of the discrete cosine transform (DCT) with the lifting one-dimensional (1-D) algorithms, two-dimensional (2-D) scheme called the binDCT. These binDCT families are derived from Chen’s and Loeffler’s plane rotation-based factorizations of DCT algorithms have also been investigated extensively [6], the DCT matrix, respectively, and the design approach can also [18]–[21], generally leading to less computational complexity be applied to a DCT of arbitrary size. Two design approaches are than the row-column application of the 1-D methods. However, presented. In the first method, an optimization program is defined, the implementation of the direct 2-D DCT requires much more and the multiplierless transform is obtained by approximating effort than that of the separable 2-D DCT. its solution with dyadic values. In the second method, a general lifting-based scaled DCT structure is obtained, and the analytical The theoretical lower bound on the number of multiplications values of all lifting parameters are derived, enabling dyadic required for the 1-D eight-point DCT has been proven to be 11 approximations with different accuracies. Therefore, the binDCT [22], [23]. In this sense, the method proposed by Loeffler et al. -

Dynamic Range White Paper

www.vialite.com +44 (0)1793 784389 [email protected] +1 (855) 4-VIALITE [email protected] White Paper The Importance of Dynamic Range in Fiber Optic Links Traditionally satellite transponders were 36 MHz wide and Spurious Free Dynamic Range (SFDR) of an RF over fiber link was less important. Ultra-wide dynamic range fiber optic links were a “nice-to- have” because the same product could be used for both the up and down links. However now, with High Throughput Satellites (HTS) which have transponder bandwidths of 500 or 800 MHz, the signals have increased hugely and consequently so have the demands on dynamic range. This means that ultra-wide dynamic range fiber optic links have become a “must-have” for anyone transporting HTS signals. Within this document we compare the SFDR and real dynamic range obtained with HTS satellite signals, and demonstrate why RF over fiber links used in satellite teleports should have a SFDR of 110 dB/Hz2/3 or better for 500 MHz wide signals. As the satellite industry moves towards increasing mobile data capacity, through the use of new satellites and wider channel bandwidths, the demand on higher link dynamic range has increased. Calculating Spurious Free Dynamic Range SFDR is a measure of the dynamic range of a fiber optic link and is relative to 1 Hz of bandwidth - which is not particularly relevant as most signals are much greater than 1 Hz. To calculate SFDR you must use the thermal noise floor (kTB), the noise figure (nf), and the third order intercept point (IP3). -

Linear-Logarithmic CMOS Image Sensor with Reduced FPN Using Photogate and Cascode MOSFET †

Proceedings Linear-Logarithmic CMOS Image Sensor with Reduced FPN Using Photogate and Cascode MOSFET † Myunghan Bae 1, Byung-Soo Choi 1, Sang-Hwan Kim 1, Jimin Lee 1, Chang-Woo Oh 2, Pyung Choi 1 and Jang-Kyoo Shin 1,* 1 School of Electronics Engineering, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 41566, Korea; [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (B.-S.C.); [email protected] (S.-H.K.); [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (P.C.) 2 Department of Sensor and Display Engineering, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 41566, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-53-950-5531 † Presented at the Eurosensors 2017 Conference, Paris, France, 3–6 September 2017. Published: 18 August 2017 Abstract: We propose a linear-logarithmic CMOS image sensor with reduced fixed pattern noise (FPN). The proposed linear-logarithmic pixel based on a conventional 3-transistor active pixel sensor (APS) structure has additional circuits in which a photogate and a cascade MOSFET are integrated with the pixel structure in conjunction with the photodiode. To improve FPN, we applied the PMOSFET hard reset method as a reset transistor instead of NMOSFET reset normally used in APS. The proposed pixel has been designed and fabricated using 0.18-μm 1-poly 6-metal standard CMOS process. A 120 × 240 pixel array of test chip was divided into 2 different subsections with 60 × 240 sub-arrays, so that the proposed linear-logarithmic pixel with reduced FPN could be compared with the conventional linear-logarithmic pixel. -

Neuromorphic Camera Guided High Dynamic Range Imaging

Neuromorphic Camera Guided High Dynamic Range Imaging Jin Han1 Chu Zhou1 Peiqi Duan2 Yehui Tang1 Chang Xu3 Chao Xu1 Tiejun Huang2 Boxin Shi2∗ 1Key Laboratory of Machine Perception (MOE), Dept. of Machine Intelligence, Peking University 2National Engineering Laboratory for Video Technology, Dept. of Computer Science, Peking University 3School of Computer Science, Faculty of Engineering, University of Sydney Abstract Conventional camera Reconstruction of high dynamic range image from a sin- gle low dynamic range image captured by a frame-based Intensity map guided LDR image HDR network conventional camera, which suffers from over- or under- 퐼 exposure, is an ill-posed problem. In contrast, recent neu- romorphic cameras are able to record high dynamic range scenes in the form of an intensity map, with much lower Intensity map spatial resolution, and without color. In this paper, we pro- 푋 pose a neuromorphic camera guided high dynamic range HDR image 퐻 imaging pipeline, and a network consisting of specially Neuromorphic designed modules according to each step in the pipeline, camera which bridges the domain gaps on resolution, dynamic range, and color representation between two types of sen- Figure 1. An intensity map guided HDR network is proposed to sors and images. A hybrid camera system has been built fuse the LDR image from a conventional camera and the intensity to validate that the proposed method is able to reconstruct map captured by a neuromorphic camera, to reconstruct an HDR quantitatively and qualitatively high-quality high dynamic image. range images by successfully fusing the images and inten- ing attention of researchers. Neuromorphic cameras have sity maps for various real-world scenarios.