Races of Maize in South America by Hughc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Races of Maize in Bolivia

RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E. David H. Timothy Efraín DÍaz B. U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Edgar Anderson William L. Brown NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Publication 747 Funds were provided for publication by a contract between the National Academythis of Sciences -National Research Council and The Institute of Inter-American Affairs of the International Cooperation Administration. The grant was made the of the Committee on Preservation of Indigenousfor Strainswork of Maize, under the Agricultural Board, a part of the Division of Biology and Agriculture of the National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council. RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E., David H. Timothy, Efraín Díaz B., and U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Calle, Edgar Anderson, and William L. Brown Publication 747 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Washington, D. C. 1960 COMMITTEE ON PRESERVATION OF INDIGENOUS STRAINS OF MAIZE OF THE AGRICULTURAL BOARD DIVISIONOF BIOLOGYAND AGRICULTURE NATIONALACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONALRESEARCH COUNCIL Ralph E. Cleland, Chairman J. Allen Clark, Executive Secretary Edgar Anderson Claud L. Horn Paul C. Mangelsdorf William L. Brown Merle T. Jenkins G. H. Stringfield C. O. Erlanson George F. Sprague Other publications in this series: RACES OF MAIZE IN CUBA William H. Hatheway NAS -NRC Publication 453 I957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN COLOMBIA M. Roberts, U. J. Grant, Ricardo Ramírez E., L. W. H. Hatheway, and D. L. Smith in collaboration with Paul C. Mangelsdorf NAS-NRC Publication 510 1957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN CENTRAL AMERICA E. -

Ecosystems and Agro-Biodiversity Across Small and Large-Scale Maize Production Systems, Feeder Study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food”

Ecosystems and agro-biodiversity across small and large-scale maize production systems, feeder study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food” i Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge TEEB and the Global Alliance for the Future of Food on supporting this project. We would also like to acknowledge the technical expertise provided by CONABIO´s network of experts outside and inside the institution and the knowledge gained through many years of hard and very robust scientific work of the Mexican research community (and beyond) tightly linked to maize genetic diversity resources. Finally we would specially like to thank the small-scale maize men and women farmers who through time and space have given us the opportunity of benefiting from the biological, genetic and cultural resources they care for. Certification All activities by Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, acting in administrative matters through Nacional Financiera Fideicomiso Fondo para la Biodiversidad (“CONABIO/FFB”) were and are consistent under the Internal Revenue Code Sections 501 (c)(3) and 509(a)(1), (2) or (3). If any lobbying was conducted by CONABIO/FFB (whether or not discussed in this report), CONABIO/FFB complied with the applicable limits of Internal Revenue Code Sections 501(c)(3) and/or 501(h) and 4911. CONABIO/FFB warrants that it is in full compliance with its Grant Agreement with the New venture Fund, dated May 15, 2015, and that, if the grant was subject to any restrictions, all such restrictions were observed. How to cite: CONABIO. 2017. Ecosystems and agro-biodiversity across small and large-scale maize production systems, feeder study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food”. -

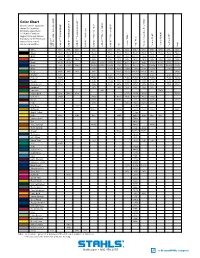

Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® Equivalent Shown

™ ™ II ® Color Chart ® ® ® ® Closest Pantone® equivalent shown. Due to printing limitations, colors shown 5807 Reflective ® ® ™ ® ® and Pantone numbers ® ™ suggested may vary from ac- ECONOPRINT GORILLA GRIP Fashion-REFLECT Reflective Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP ® ® ® ® ® ® ® tual colors. For the truest color ® representation, request Scotchlite our material swatches. ™ CAD-CUT 3M CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT CAD-CUT Felt Perma-TWILL Poly-TWILL Thermo-FILM Thermo-FLOCK Thermo-GRIP Vinyl Pressure Sensitive Poly-TWILL Sensitive Pressure CAD-CUT White White White White White White White White White* White White White White White Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black* Black Black Black Black Black Gold 1235C 136C 137C 137C 123U 715C 1375C* 715C 137C 137C 116U Red 200C 200C 703C 186C 186C 201C 201C 201C* 201C 186C 186C 186C 200C Royal 295M 294M 7686C 2747C 7686C 280C 294C 294C* 294C 7686C 2758C 7686C 654C Navy 296C 2965C 7546C 5395M 5255C 5395M 276C 532C 532C* 532C 5395M 5255C 5395M 5395C Cool Gray Warm Gray Gray 7U 7539C 7539C 415U 7538C 7538C* 7538C 7539C 7539C 2C Kelly 3415C 341C 340C 349C 7733C 7733C 7733C* 7733C 349C 3415C Orange 179C 1595U 172C 172C 7597C 7597C 7597C* 7597C 172C 172C 173C Maroon 7645C 7645C 7645C Black 5C 7645C 7645C* 7645C 7645C 7645C 7449C Purple 2766C 7671C 7671C 669C 7680C 7680C* 7680C 7671C 7671C 2758U Dark Green 553C 553C 553C 447C 567C 567C* 567C 553C 553C 553C Cardinal 201C 188C 195C 195C* 195C 201C Emerald 348 7727C Vegas Gold 616C 7502U 872C 4515C 4515C 4515C 7553U Columbia 7682C 7682C 7459U 7462U 7462U* 7462U 7682C Brown Black 4C 4675C 412C 412C Black 4C 412U Pink 203C 5025C 5025C 5025C 203C Mid Blue 2747U 2945U Old Gold 1395C 7511C 7557C 7557C 1395C 126C Bright Yellow P 4-8C Maize 109C 130C 115U 7408C 7406C* 7406C 115U 137C Canyon Gold 7569C Tan 465U Texas Orange 7586C 7586C 7586C Tenn. -

Common Corn Smut Tianna Jordan*, UW-Madison Plant Pathology

D0031 Provided to you by: Common Corn Smut Tianna Jordan*, UW-Madison Plant Pathology What is common corn smut? Common corn smut is a fungal disease that affects field, pop, and sweet corn, as well as the corn relative teosinte (Zea mexicana). Common corn smut is generally not economically significant except in sweet corn where relatively low levels of disease make the crop aesthetically unappealing for fresh market sale and difficult to process for freezing or canning. Interestingly, the early stages of common corn smut are eaten as a delicacy in Mexico where the disease is referred to as huitlacoche (see UW Plant Disease Facts D0065, Huitlacoche). What does common corn smut look like? Common corn smut leads to tumor-like swellings (i.e., galls) on corn ears, kernels, tassels, husks, leaves, stalks, buds and, less frequently, on aerial roots. Some galls (particularly those on leaves) are small and hard. More typically, however, galls are fleshy and smooth, silvery-white to green, and can be four to five inches in diameter. As fleshy galls mature, their outer surfaces become papery and brittle, and their inner tissues become powdery and black. Galls eventually rupture, releasing the powder (i.e., the spores of the causal fungus). Where does common corn smut come from? Common corn smut is caused by the fungus Ustilago maydis, which can survive for several years as spores in soil and corn residue. Spores are spread by wind or through water splashing up onto young plants. Spores can also be spread through the Common corn smut leads to tumor-like galls manure of animals that have eaten infected corn. -

The Comparative Study of Bt Corn and Conventional Corn Regarding the Ostrinia Nubilalis Attack and the Fusarium Spp

Romanian Biotechnological Letters Vol. 23, No. 4, 2018 Copyright © 2018 University of Bucharest Printed in Romania. All rights reserved ORIGINAL PAPER The comparative study of Bt corn and conventional corn regarding the Ostrinia nubilalis attack and the Fusarium spp. infestation in the central part of Oltenia DOI: 10.26327/RBL2018.138 Received for publication, April, 27, 2016 Accepted, June, 30, 2017 VIORICA URECHEAN 1, DORINA BONEA2* 1Agricultural Research and Development Station Simnic- Craiova, Dolj, Romania 2 University of Craiova, Faculty of Agronomy, Dolj, Romania *Address for correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract Ostrinia nubilalis or the European corn borer is a dangerous corn pest, especially in warmer Romanian regions, including Oltenia. To compare the attack produced by O. nubilalis on the transgenic Bt corn (MON 810) vs. the conventional corn (Deliciul verii), there were performed studies on unirrigated soil, in conditions of natural infestation. The experiments were made at ARDS Şimnic (in the central part of Oltenia) in 2012 and 2013. It was proven that there is a functional direct relation between the O. nubilalis attack and Fusarium spp, in that an intensive Ostrinia attack favors the installation of Fusarium-type pathogens. Our results have shown that the use of transgenic hybrid Bt-MON 810, which contains the gene CrylAb, reduced the O. nubilalis attack by 99.55% in 2012 and by 100.0% in 2013, and the infestation with Fusarium spp. by 95.54% in 2012 and by 100.0% in 2013. Therefore, Bt-MON 810 corn can reduce the damages caused to corn harvest by Ostrinia and implicitly by Fusarium, both quantitatively and qualitatively. -

Zea Mays Subsp

Unclassified ENV/JM/MONO(2003)11 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 23-Jul-2003 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English ENVIRONMENT DIRECTORATE JOINT MEETING OF THE CHEMICALS COMMITTEE AND Unclassified ENV/JM/MONO(2003)11 THE WORKING PARTY ON CHEMICALS, PESTICIDES AND BIOTECHNOLOGY Cancels & replaces the same document of 02 July 2003 Series on Harmonisation of Regulatory Oversight in Biotechnology, No. 27 CONSENSUS DOCUMENT ON THE BIOLOGY OF ZEA MAYS SUBSP. MAYS (MAIZE) English - Or. English JT00147699 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format ENV/JM/MONO(2003)11 Also published in the Series on Harmonisation of Regulatory Oversight in Biotechnology: No. 4, Industrial Products of Modern Biotechnology Intended for Release to the Environment: The Proceedings of the Fribourg Workshop (1996) No. 5, Consensus Document on General Information concerning the Biosafety of Crop Plants Made Virus Resistant through Coat Protein Gene-Mediated Protection (1996) No. 6, Consensus Document on Information Used in the Assessment of Environmental Applications Involving Pseudomonas (1997) No. 7, Consensus Document on the Biology of Brassica napus L. (Oilseed Rape) (1997) No. 8, Consensus Document on the Biology of Solanum tuberosum subsp. tuberosum (Potato) (1997) No. 9, Consensus Document on the Biology of Triticum aestivum (Bread Wheat) (1999) No. 10, Consensus Document on General Information Concerning the Genes and Their Enzymes that Confer Tolerance to Glyphosate Herbicide (1999) No. 11, Consensus Document on General Information Concerning the Genes and Their Enzymes that Confer Tolerance to Phosphinothricin Herbicide (1999) No. -

Popped Secret: the Mysterious Origin of Corn Film Guide Educator Materials

Popped Secret: The Mysterious Origin of Corn Film Guide Educator Materials OVERVIEW In the HHMI film Popped Secret: The Mysterious Origin of Corn, evolutionary biologist Dr. Neil Losin embarks on a quest to discover the origin of maize (or corn). While the wild varieties of common crops, such as apples and wheat, looked much like the cultivated species, there are no wild plants that closely resemble maize. As the film unfolds, we learn how geneticists and archaeologists have come together to unravel the mysteries of how and where maize was domesticated nearly 9,000 years ago. KEY CONCEPTS A. Humans have transformed wild plants into useful crops by artificially selecting and propagating individuals with the most desirable traits or characteristics—such as size, color, or sweetness—over generations. B. Evidence of early maize domestication comes from many disciplines including evolutionary biology, genetics, and archaeology. C. The analysis of shared characteristics among different species, including extinct ones, enables scientists to determine evolutionary relationships. D. In general, the more closely related two groups of organisms are, the more similar their DNA sequences will be. Scientists can estimate how long ago two populations of organisms diverged by comparing their genomes. E. When the number of genes is relatively small, mathematical models based on Mendelian genetics can help scientists estimate how many genes are involved in the differences in traits between species. F. Regulatory genes code for proteins, such as transcription factors, that in turn control the expression of several—even hundreds—of other genes. As a result, changes in just a few regulatory genes can have a dramatic effect on traits. -

A Study of the Pollination of the Sour Cherry, Prunus Cerasus Linnaeus

THE S IS on A STUDY OF THE POLLINATION OF THE SOUR CHERRY PRTJNIJS ERASUS L INNAEUS Submitted to the OREGON AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Require!rßnte For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE by Loue Arrowood 1etchor May 5, 126. PRQYO: Redacted for privacy £eoc1at ProfEor of In ohare of Major Redacted for privacy 4-.----- - - - - 'j Road of Dopartnent of Redacted for privacy of Redacted for privacy atzn of comi.ttee on Graivate Study. III QNQLEDGE lIE NT The writer wishes to express hie appreciation to Dr. E. M. Harvey of the Research Division, for hie untiring help and many suggestion. which aided greatly in carrying out the following prob- leì; and to Prcfesaor C. E. Schuster, for his critciems and timely suggestions on the field work; and to Mr. R. V. Rogers of Eugene, for use of his trees; and to Professor J. S. Brown, who made this problem poasble. Iv - INDEX- Page. Title Page I Approval Sheet II Acknowledgment III Index IV List of Table. V List of Plates VI Introduction i Review of Literature 3 Methods and Materials 10 Germination Tests 12 Preliminary Survey of Work 14 Sterility Tests 15 Cross Pollination Studies 20 Dicusiion 28 Si.ary 29 Histological Studies 31 Methode and Materials A - Bud Development Studies 31 B - Pieti]. Studies 33 Methods and Materials 33 Diecuseion of Results A - Bud Development Studies 35 B - Pistil Studies 37 Swary 38 Explanation of Plates 39 Platos 42 BiblIography 47 V -LIST OF TABLES- Table No. Pag. I Germination Teats 13 II Sterility Test. -

X-Disease in Peaches 44

X-disease pathogen Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni. Hosts Sweet and tart cherry, peach and nectarine. Alternate hosts include clovers, dandelion, chokecherry, almond and several wild plum and cherry species. Time of concern Management is focused on removing infected hosts before leafhopper spread can occur. Symptoms and damage William Shane, MSU Extension Peach and nectarine leaves develop red, necrotic Sweet cherry leaf with enlarged leaf-like stipules at the base of the areas that drop out, leaving a shot-hole effect and petiole due to X-disease. tattered leaves. Defoliation at the base of a shoot gives a poodle tail or pompom appearance. Fruit on infected branches is smaller, lacks flavor often with a bitter taste and may drop before ripening. Usually by the third year after infection, most branches will show symptoms. Young trees die within one to two years after the first symptoms appear. Older trees gradually decline in vigor. Sweet and tart cherries infected with X-disease phy- toplasma show stunted growth, enlarged stipules and immature, small, poorly colored fruit. Infected cherry trees on mahaleb rootstock decline quickly, whereas those on mazzard rootstock may persist for many years. Pest cycle Chokecherry is an important natural reservoir of peach X-disease phytoplasma in eastern USA. Infected sweet and sour cherries, especially on maz- zard rootstock, can be sources of X-disease, although chokecherry is often the principal reservoir. Other reservoirs of X-disease include weeds such as clover and dandelion. Peaches and nectarines, although severely affected William Shane, MSU Extension by the pathogen, are poor hosts for further disease Peach leaf with wine-red splotches typical of X-disease symptoms. -

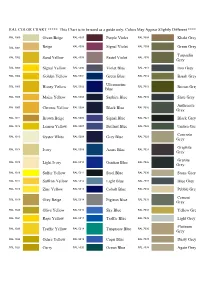

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Root-Hair Endophyte Stacking in Finger Millet Creates a Physicochemical Barrier to Trap the Fungal Pathogen Fusarium Graminearum

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Root-hair endophyte stacking in finger millet creates a physicochemical barrier to trap the fungal pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7b87c4z1 Journal Nature microbiology, 1(12) ISSN 2058-5276 Authors Mousa, Walaa K Shearer, Charles Limay-Rios, Victor et al. Publication Date 2016-09-26 DOI 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.167 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLES PUBLISHED: 26 SEPTEMBER 2016 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 16167 | DOI: 10.1038/NMICROBIOL.2016.167 Root-hair endophyte stacking in finger millet creates a physicochemical barrier to trap the fungal pathogen Fusarium graminearum Walaa K. Mousa1,2, Charles Shearer1, Victor Limay-Rios3, Cassie L. Ettinger4,JonathanA.Eisen4 and Manish N. Raizada1* The ancient African crop, finger millet, has broad resistance to pathogens including the toxigenic fungus Fusarium graminearum. Here, we report the discovery of a novel plant defence mechanism resulting from an unusual symbiosis between finger millet and a root-inhabiting bacterial endophyte, M6 (Enterobacter sp.). Seed-coated M6 swarms towards root-invading Fusarium and is associated with the growth of root hairs, which then bend parallel to the root axis, subsequently forming biofilm-mediated microcolonies, resulting in a remarkable, multilayer root-hair endophyte stack (RHESt). The RHESt results in a physical barrier that prevents entry and/or traps F. graminearum, which is then killed. M6 thus creates its own specialized killing microhabitat. Tn5-mutagenesis shows that M6 killing requires c-di-GMP-dependent signalling, diverse fungicides and resistance to a Fusarium-derived antibiotic. Further molecular evidence suggests long-term host–endophyte– pathogen co-evolution. -

Prunus X Yedoensis Yoshino Cherry1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-523 October 1994 Prunus x yedoensis Yoshino Cherry1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Yoshino Cherry grows quickly to 20 feet, has beautiful bark marked with prominent lenticels but is a relatively short-lived tree (Fig. 1). It has upright to horizontal branching, making it ideal for planting along walks and over patios. The white to pink flowers which occur in early spring before the leaves develop are sometimes damaged by late frosts or very windy conditions. This is the tree along with ‘Kwanzan’ Cherry in Washington, DC, which makes such a show each spring. Figure 1. Mature Yoshino Cherry. GENERAL INFORMATION DESCRIPTION Scientific name: Prunus x yedoensis Pronunciation: PROO-nus x yed-oh-EN-sis Height: 35 to 45 feet Common name(s): Yoshino Cherry Spread: 30 to 40 feet Family: Rosaceae Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a USDA hardiness zones: 5B through 8A (Fig. 2) regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more Origin: not native to North America or less identical crown forms Uses: Bonsai; wide tree lawns (>6 feet wide); Crown shape: round; vase shape medium-sized tree lawns (4-6 feet wide); Crown density: moderate recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or Growth rate: medium for median strip plantings in the highway; near a deck Texture: medium or patio; shade tree; narrow tree lawns (3-4 feet wide); specimen; sidewalk cutout (tree pit); no proven urban Foliage tolerance Availability: generally available in many areas within Leaf arrangement: alternate (Fig. 3) its hardiness range Leaf type: simple Leaf margin: double serrate; serrate Leaf shape: elliptic (oval); oblong; ovate Leaf venation: banchidodrome; pinnate Leaf type and persistence: deciduous Leaf blade length: 2 to 4 inches 1.