Patripassianism, Theopaschitism and the Suffering of God Sarot, M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Historical Roots of the Death of God"

Portland State University PDXScholar Special Collections: Oregon Public Speakers Special Collections and University Archives 7-2-1968 "Historical Roots of the Death of God" Thomas J.J. Altizer Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/orspeakers Part of the History of Religion Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Altizer, Thomas J.J., ""Historical Roots of the Death of God"" (1968). Special Collections: Oregon Public Speakers. 57. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/orspeakers/57 This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections: Oregon Public Speakers by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Thomas J. J. Altizer "Historical Roots of the Death of God" July 2, 1968 Portland State University PSU Library Special Collections and University Archives Oregon Public Speakers Collection http://archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/11281 Transcribed by Nia Mayes, November 25, 2020 Audited by Carolee Harrison, February 2021 PSU Library Special Collections and University Archives presents these recordings as part of the historical record. They reflect the recollections and opinions of the individual speakers and are not intended to be representative of the views of Portland State University. They may contain language, ideas, or stereotypes that are offensive to others. MICHAEL REARDON: We’re very fortunate today to have Dr. Altizer, who is teaching on the summer faculty at Oregon State in the department of religion there, give the first in a series of two lectures. -

Sermon Notes: June 7, 2020 Focus: Trinity Sunday Lectionary Readings Trinitarian Images Are Everywhere in Our Liturgy

Sermon Notes: June 7, 2020 Focus: Trinity Sunday Lectionary Readings Trinitarian images are everywhere in our liturgy. At the same time, there are many Christian groups who reject the Trinity. Pentecostal churches (Church of God, independent Pentecostals); Jehovah’s Witness; Mormons and denominations that you’ve never heard of don’t believe “In the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” If you forget most of this sermon, just remember that Trinity is a relationship. I want to get into some theology; but my primary goal is to give you a reason to care about the Trinity or to know why you don’t care. There are lots of small pieces that one could use to cobble together a scriptural understanding of the Trinity. This is found especially in the beginning of Genesis and when people get baptized. The most explicit verse is at the end of Matthew. Therefore, go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. There is also a reference in 1st John - For there are three that testify: the Spirit, the water and the blood; and the three are in agreement. It’s a stretch to build the Trinity upon these and other oblique references, but that is exactly what the church in history has tried to do. Here are some historical “heresies” around the Trinity. I am willing to bet that one of them is your favorite. Sabellianism, Noetianism and Patripassianism Trinity is expressed in Could not find an image reference, but it leans to modal and tritheistic sensibility different “modes.” Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not distinct, but rather different faces God. -

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate by David Andrew Graham A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by David Andrew Graham 2013 The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate David Andrew Graham Master of Arts in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2013 Abstract This thesis contributes to the debate over the meaning and function of the doctrine of divine impassibility in theological and especially christological discourse. Seeking to establish the coherence and utility of the paradoxical language characteristic of the received christological tradition (e.g. the impassible Word became passible flesh and suffered impassibly), it argues that the doctrine of divine apatheia illuminates the apocalyptic and soteriological dimension of the incarnate Son’s passible life more effectively than recent reactions against it. The first chapter explores the Christology of Cyril of Alexandria and the meaning and place of apatheia within it. In light of the christological tradition which Cyril epitomized, the second chapter engages contemporary critiques and re-appropriations of impassibility, focusing on the particular contributions of Jürgen Moltmann, Robert W. Jenson, Bruce L. McCormack and David Bentley Hart. ii Acknowledgments If this thesis communicates any truth, beauty and goodness, credit belongs to all those who have shaped my life up to this point. In particular, I would like to thank the Toronto School of Theology and Wycliffe College for providing space to do theology from within the catholic church. -

Chapter 1 the Trinity in the Theology of Jürgen Moltmann

Our Cries in His Cry: Suffering and The Crucified God By Mick Stringer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology The University of Notre Dame Australia, Fremantle, Western Australia 2002 Contents Abstract................................................................................................................ iii Declaration of Authorship ................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements.............................................................................................. v Introduction.......................................................................................................... 1 1 Moltmann in Context: Biographical and Methodological Issues................... 9 Biographical Issues ..................................................................................... 10 Contextual Issues ........................................................................................ 13 Theological Method .................................................................................... 15 2 The Trinity and The Crucified God................................................................ 23 The Tradition............................................................................................... 25 Divine Suffering.......................................................................................... 29 The Rise of a ‘New Orthodoxy’................................................................. -

RCIA, Session #06: Major Heresies of the Early Church

RCIA, Session #06: Major Heresies of the Early Church Adoptionism A 2nd-3rd century heresy that affirmed that Jesus’ divine identity began with his baptism (God adopted the man Jesus to be his Son, making him divine through the gift of the Holy Spirit). It was advocated by Elipandus of Toledo and Felix of Urgel, but condemned by Pope Adrian I in 785 and again in 794. When Peter Abelard (1079-1142) renewed a modified form of this teaching in the twelfth century, it was condemned by Pope Alexander III in 1177 as a theory proposed by Peter Lombard. Apollinarianism Heretical doctrine of Appolinaris the younger (310-90), Bishop of Laodicea, that Christ had a human body and only a sensitive soul, but had not rational mind or a free human will (i.e., Jesus was not fully human). His rational soul was replaced by the Divine Logos, or Word of God. The theory was condemned by Roman councils in 377 and 381, and also by the 1st Council of Constantinople in 381. Arianism A fourth century heresy that denied the divinity of Jesus Christ. Its author was Arius (256-336), a priest of Alexandria who in 318 began to teach the doctrine that now bears his name. According to Arius, there are not three distinct persons in God, co-eternal and equal in all things, but only one person, the Father. The Son is only a creature, made out of nothing, like all other created beings. He may be called God by only by an extension of language, as the first and greatest person chosen to be divine intermediary in the creation and redemption of the world. -

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Heresy Description Origin Official

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Official Heresy Description Origin Other Condemnation Adoptionism Belief that Jesus Propounded Theodotus was Alternative was born as a by Theodotus of excommunicated names: Psilanthro mere (non-divine) Byzantium , a by Pope Victor and pism and Dynamic man, was leather merchant, Paul was Monarchianism. [9] supremely in Rome c.190, condemned by the Later criticized as virtuous and that later revived Synod of Antioch presupposing he was adopted by Paul of in 268 Nestorianism (see later as "Son of Samosata below) God" by the descent of the Spirit on him. Apollinarism Belief proposed Declared to be . that Jesus had by Apollinaris of a heresy in 381 by a human body Laodicea (died the First Council of and lower soul 390) Constantinople (the seat of the emotions) but a divine mind. Apollinaris further taught that the souls of men were propagated by other souls, as well as their bodies. Arianism Denial of the true The doctrine is Arius was first All forms denied divinity of Jesus associated pronounced that Jesus Christ Christ taking with Arius (ca. AD a heretic at is "consubstantial various specific 250––336) who the First Council of with the Father" forms, but all lived and taught Nicea , he was but proposed agreed that Jesus in Alexandria, later exonerated either "similar in Christ was Egypt . as a result of substance", or created by the imperial pressure "similar", or Father, that he and finally "dissimilar" as the had a beginning declared a heretic correct alternative. in time, and that after his death. the title "Son of The heresy was God" was a finally resolved in courtesy one. -

CHURCH HISTORY the Council of Nicea Early Church History, Part 13 by Dr

IIIM Magazine Online, Volume 1, Number 27, August 30 to September 5, 1999 CHURCH HISTORY The Council of Nicea Early Church History, part 13 by Dr. Jack L. Arnold I. INTRODUCTION A. As the church grew in numbers, the false church (heretics) grew numerically also. It became increasingly more difficult to control the general thinking of all Christians on the fundamentals of the Christian Faith. Thus, there was a need to gather the major leaders together to settle different theological and practical matters. These gatherings were called “councils.” B. The first major council was in the first century: the Jerusalem Council. There were four major councils in early Church history which are of great significance: (1) the Council of Nicea; (2) the Council of Constantinople; (3) the Council of Ephesus; and (4) the Council of Chalcedon. II. HERESIES OPPOSED TO THE TRINITY A. The great question which occupied the mind of the early church for three hundred years was the relationship of the Son to the Father. There were a great many professing Christians who were not Trinitarian. B. Monarchianism: Monarchianism was a heresy that attempted to maintain the unity of God (one God), for the Bible teaches that “the Lord our God is one God.” Monarchianism, however, failed to distinguish the Persons in the Godhead, and the deity of Christ became more like a power or influence. This heresy was opposed by Tertullian and Hippolytus in the west, and by Origen in the east. Tertullian was the first to assert clearly the tri-personality of God, and to maintain the substantial unity of the three Persons of the Godhead. -

Being of God: a Trinitarian Critique of Postmodern A/Theology

RICE UNIVERSITY (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE (NON)BEING OF GHD: A TRINITARIAN CRITIQUE OF POSTMODERN A/THEOLOGY by B. KEITH PUTT A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE Niels C. Nielsen, Jr.,Director Professor Emeritus of Philoso¬ phy and Religious Thought Werner H. Kelber Isla Carroll Turner and Percy E. Turner Professor of Reli¬ gious Studies Stjeven G. Crowell Associate Professor of Philoso¬ phy Houston, Texas May, 1995 Copyright B. Keith Putt 1995 ABSTRACT (DE) CONSTRUCTING THE (NON) BEING OF G8D: A TRINITARIAN CRITIQUE OF POSTMODERN A/THEOLOGY by B. KEITH PUTT Langdon Gilkey maintained in 1969 that theological language was in "ferment" over whether "God" could be ex¬ pressed in language. He argued that "radical theology," specifically the kenotic christology in Altizer's "death of God" theology, best represented that ferment. Some twenty- five years later, in the postmodern context of the 1990's, whether one can speak of God and, if so, how remain promi¬ nent issues for philosophers of religion and theologians. One of the most provocative contemporary approaches to these questions continues to focus on the "death of God." Mark Taylor's a/theology attempts to "do" theology after the divine demise by thinking the end of theology without ending theological thinking. Taylor's primary thesis, predicated upon his reading of Jacques Derrida's deconstruetive philos¬ ophy, is that God gives way to the sacred and the sacred may be encountered only within the "divine milieu" of writing. God is dead, the self is dead, history has no structure, and language cannot be totalized in books; consequently, theo¬ logy must be errant and textually disseminative. -

Early Christological Heresies

Early Christological Heresies Introduction When a Bible student reads some of the history of the early church regarding the theological debates about the Trinity and the natures of Christ, he can be easily overwhelmed with detail and thrown into complete confusion. Doctrines such as Apollinarianism or Monothelitism just flummox him. Sadly some of the books and dictionary articles on these subjects are technical, full of jargon and confusing. Indeed, it is not easy even for students who have studied this for some time. Well, this paper is written to try to make this complex web of theology a little bit easier to understand. The reason for this difficulty is the complexity of the wonderful person of Christ. The theological statements are so difficult because they are trying to evaluate the depths and glory of something that is too high for us to grasp; we can only seek to encapsulate this glory in human terms as best as we can. Consequently, as a clearer doctrinal statement arose, heretics quickly appeared to countermand that because they felt that the former teaching denied or contradicted something else about Christ; thus the church went back and forth in a pendulum effect either overstating Christ’s deity or his humanity (see Appendix One). Another factor is that in post-apostolic early church there was no single orthodox party. As new ideas arose, there would be a number of parties vying for support. For instance, as Docetism became a threat, some Christians confronted it with a type of Adoptionist doctrine, others with more Biblical teachings; but at the same time there were people with Modalistic theology. -

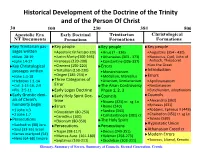

Historical Development of the Doctrine of the Trinity

Historical Development of the Doctrine of the Trinity and of the Person Of Christ 30 100 230 381 500 Apostolic Era Early Doctrinal Trinitarian Christological NT Documents Formations Formations Formations Key Trinitarian pas‐ Key people Key people Key people sages written •Apostolic fathers(60‐120) •Arius (? ‐ 336) •Augustine (354 ‐ 430) •Matt. 28:19 •Justin Martyr(100‐166) •Athanasius (303 ‐ 373) •Nestorius, Cyril, John of •John 14‐17 •Irenaeus (120‐200) •Constantine (306‐337) Antioch, Theodoret Key Christological •Clement (150‐220) Errors •Leo the Great passages written •Tertullian (150‐230) •Monarchianism Introduction •John 1:1‐18 •Origen (185‐254) e •Modalism, Marcellus Errors •Hebrews 1:1‐14 Three Categories of •Arianism, Semiarianism •Apollinarianism •Col. 1:15‐16, 2:9 Error The Arian Controversy •Nestorianism •Phi. 2:5‐11 Early Logos Doctrine Phase 1, 2, 3 •Eutichianism, adoptionism Early Gnostic deni‐ Early Holy Spirit Doc‐ Councils Councils als of Christ’s trine •Nicaea (325) cr. sg Ln •Alexandria (362) humanity begin •Ephesus (431) Errors •Rome (340) •Robbers, Ephesus II (449) •1 John 4:3 •Gnosticism (80‐250) •Sardica (343) •2 John 1:7 •Constantinople (381) cr. •Chalcedon (451) cr. sg Ln •Cerinthus (100) •Toledo (589) Persecutions •Ebionism (80‐350) The Holy Spirit Hypostatic Union •Sanhedrin (30) Jeru. Persecutions Persecutions •Saul (33‐35) Israel Athanasian Creed cr •Trajan (98‐117) •Decius (249‐251) •James martyred (54) •Marcus Aure. (161‐180) •Valerian (258‐273) Modern Errors •Nero (64‐68) Empire •Septimus (193‐211) •Diocletian (303‐311) •Socinus, Liberal, Kenotic Glossary, Summary of Errors, Summary of Councils, Eternal Generation, Creeds Historical Development Early Doctrinal Formations 100 - 230 A.D. -

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies Edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press. Cover design by David Manahan, o.s.b. Cover symbol by Frank Kacmarcik, obl.s.b. © 2007 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, P.O. Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies / edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff. p. cm. “A Michael Glazier book.” ISBN-13: 978-0-8146-5856-7 (alk. paper) 1. Religion—Dictionaries. 2. Religions—Dictionaries. I. Espín, Orlando O. II. Nickoloff, James B. BL31.I68 2007 200.3—dc22 2007030890 We dedicate this dictionary to Ricardo and Robert, for their constant support over many years. Contents List of Entries ix Introduction and Acknowledgments xxxi Entries 1 Contributors 1519 vii List of Entries AARON “AD LIMINA” VISITS ALBIGENSIANS ABBA ADONAI ALBRIGHT, WILLIAM FOXWELL ABBASIDS ADOPTIONISM -

Denying the Involvement of the Father in the Son's Work

The Error of Denying the Involvement of the Father in the Son’s Work In the special “We Were Wrong” issue of the Christian Research Journal, veteran apologist Gretchen Passantino, who participated in the earliest criticisms of the local churches published in the United States over thirty years ago, made an impassioned appeal. She asked her fellow apologists and the signers of an open letter criticizing the teachings of Living Stream Ministry (LSM) and the local churches to reconsider their condemnation, saying that her own further research had changed her opinion.1 Norman Geisler and Ron Rhodes rejected her appeal out of hand, saying: However, it is clear that truth does not always reside with the persons who have read more or studied longer. Rather, it rests with those who can reason best from the evidence.2 Thus, Geisler and Rhodes dismissed the need for further research in spite of the lapse of thirty- five years since the original research was performed in which Gretchen Passantino participated. Instead, Geisler and Rhodes assert their own superior ability to reason apart from further evidence. In fact, their reasoning is flawed in many respects. This article examines one such case in which Geisler and Rhodes’ “reasoning” is woefully deficient. Geisler and Rhodes backhandedly accuse the local churches of espousing the ancient heresy of patripassianism, which states that Jesus Christ, as the Son of God, was simply the Father in another mode of existence, so that it was the Father who suffered on the cross. Geisler and Rhodes say: Likewise, the LC’s alleged repudiation of patripassianism (the heresy that the Father suffered on the cross-17) is unconvincing since they also claim (and CRI apparently supports) the view, based on the doctrine of coinherence, that both the Father and the Son are involved in each other’s activities.