Carnivore-Livestock Conflicts in Chile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humboldt Penguin Spheniscus Humboldti Population in Chile: Counts of Moulting Birds, February 1999–2008

Wallace & Araya: Humboldt Penguin population in Chile 107 HUMBOLDT PENGUIN SPHENISCUS HUMBOLDTI POPULATION IN CHILE: COUNTS OF MOULTING BIRDS, FEBRUARY 1999–2008 ROBERTA S. WALLACE1 & BRAULIO ARAYA2 1Milwaukee County Zoo, 10001 W. Blue Mound Road, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA ([email protected]) 2Calle Lima 193. Villa Alemana, V Región, Chile Received 19 August 2014, accepted 9 December 2014 SUMMARY WALLACE, R.S. & ARAYA, B. 2015. Humboldt Penguin Spheniscus humboldti population in Chile: counts of moulting birds, February 1999–2008. Marine Ornithology 43: 107–112 We conducted annual counts of moulting Humboldt Penguins roosting on the mainland coast and on offshore islands in north and central Chile during 1999–2008. The census area included the known major breeding colonies in Chile, where many penguins moult, as well as other sites. Population size was relatively stable across years, with an average of 33 384 SD 2 372 (range: 28 642–35 284) penguins counted, but the number of penguins found at any individual site could vary widely. Shifting penguin numbers suggest that penguins tend to aggregate to moult where food is abundant. While many of the major breeding sites are afforded some form of protected status, two sites with sizable penguin populations, Tilgo Island and Pájaros-1 Island, have no official protection. These census results provide a basis upon which future population trends can be compared. Key words: penguin, Spheniscus humboldti, census, Chile INTRODUCTION penguin taking less than three weeks to moult (Paredes et al. 2003). Penguins remain on land during moult, and they return to The Humboldt Penguin Spheniscus humboldti is a species endemic sea immediately after moulting (Zavalaga & Paredes 1997). -

Large Rock Avalanches and River Damming Hazards in the Andes of Central Chile: the Case of Pangal Valley, Alto Cachapoal

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-6079, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Large rock avalanches and river damming hazards in the Andes of central Chile: the case of Pangal valley, Alto Cachapoal Sergio A. Sepulveda (1,2), Diego Chacon (2), Stella M. Moreiras (3), and Fernando Poblete (1) (1) Universidad de O0Higgins, Instituto de Ciencias de la Ingeniería, Rancagua, Chile ([email protected]), (2) Universidad de Chile, Departamento de Geología, Santiago, Chile, (3) CONICET – IANIGLA- CCT, Mendoza, Argentina A cluster of five rock avalanche deposits of volumes varying from 1.5 to 150 millions of cubic metres located in the Pangal valley, Cachapoal river basin in the Andes of central Chile is studied. The landslides are originated in volcanic rocks affected by localised hydrothermal alteration in a short section of the fluvial valley. The largest rock avalanches, with deposit thicknesses of up to about 100 m, have blocked the valley to be later eroded by the Pangal river. Lacustrine deposits can be found upstream. A detailed geomorphological survey of the valley and dating of the landslide deposits is being performed, in order to assess the likelihood of new large volume landslide events with potential of river damming. Such events would endanger hydroelectric facilities and human settlements downstream. A total of eighteen potential landslide source areas were identified, with potential of damming up to 10^7 million cubic metres. This case study illustrates a poorly studied hazard of large slope instabilities and related river damming in the Chilean Andes, extensively covered by large landslide deposits along their valleys. -

La Campana-Peñuelas Biosphere Reserve in Central Chile: Threats and Challenges in a Peri-Urban Transition Zone

Management & Policy Issues eco.mont - Volume 7, Number 1, January 2015 66 ISSN 2073-106X print version ISSN 2073-1558 online version: http://epub.oeaw.ac.at/eco.mont La Campana-Peñuelas Biosphere Reserve in Central Chile: threats and challenges in a peri-urban transition zone Alejandro Salazar, Andrés Moreira-Muñoz & Camilo del Río Keywords: regional planning, sustainability science, ecosystem services, priority conservation sites, environmental threats Abstract Profile UNESCO biosphere reserves are territories especially suited as laboratories for Protected area sustainability. They form a network of more than 600 units worldwide, intended to be key sites for harmonization of the nature-culture interface in the wide diversity La Campana-Peñuelas of ecosystems existing on Earth. This mission is especially challenging in territories with high levels of land transformation and urbanization. The La Campana-Peñuelas Biosphere Reserve (BR) is one of these units: located in one of the world’s conserva- BR tion priority ecosystems, the Central Chilean Mediterranean ecoregion, it is at the same time one of the globally highly threatened spaces since the biota in this terri- Mountain range tory coexist with the most densely populated Chilean regions. This report deals with the main threats and land-use changes currently happening in the transition zone of Andes La Campana-Peñuelas BR, which pose several challenges for the unit as an effective model of sustainability on a regional scale. Country Chile Introduction local endemic species (Luebert et al. 2009; Hauenstein et al. 2009), see Figure 1. UNESCO biosphere reserves (BRs) can be consid- Recognizing that Central Chile possesses great spe- ered laboratories for sustainability (Bridgewater 2002; cies richness and endemism, which are under immi- Hadley 2011; Moreira-Muñoz & Borsdorf 2014). -

The Air Quality in Chile: and F

em • feature by Luis Díaz-Robles, Herman Saavedra, Luis Schiappacasse, The Air Quality in Chile: and F. Cereceda-Balic Today, with a population of 16 million, Chile is one of South America’s most Luis Díaz-Robles, 1 Herman Saavedra, and stable and prosperous nations. It leads Latin America in human development, Luis Schiappacasse are competitiveness, income per capita, globalization, economic freedom, low per- with the Air Quality Unit at the Catholic University ception of corruption, and state of peace.2 It also ranks high regionally in terms of Temuco in Chile. F. Cereceda-Balic is with of freedom of the press and democratic development. Its economy is recovering CETAM at the Universidad Técnica Federico Santa fast from the last global economy recession, growing by 5.2% in 2010. The María in Chile. E-mail: Monthly Economic Activity Grow Index for March 2011 was 15.2%, the highest [email protected]. value since 1992.3 In May 2010, Chile became the first South American country to join the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). However, Chile has serious air quality problems. Cerro Alegre Hill, Valparaiso, Chile. 28 em august 2011 awma.org Copyright 2011 Air & Waste Management Association 20 Years of Challenge Geography and Climate subtropical anticyclone marks for much of the year Chile occupies a long, narrow coastal strip between the emergence of the phenomenon of temperature the Andes Mountains to the east and the Pacific inversion and a heavy coastal fog (called “vaguada Ocean to the west, with small mountains in the costera” in Spanish). This favors the generation of center of the country, called the Coast Mountains. -

The Mw 8.8 Chile Earthquake of February 27, 2010

EERI Special Earthquake Report — June 2010 Learning from Earthquakes The Mw 8.8 Chile Earthquake of February 27, 2010 From March 6th to April 13th, 2010, mated to have experienced intensity ies of the gap, overlapping extensive a team organized by EERI investi- VII or stronger shaking, about 72% zones already ruptured in 1985 and gated the effects of the Chile earth- of the total population of the country, 1960. In the first month following the quake. The team was assisted lo- including five of Chile’s ten largest main shock, there were 1300 after- cally by professors and students of cities (USGS PAGER). shocks of Mw 4 or greater, with 19 in the Pontificia Universidad Católi- the range Mw 6.0-6.9. As of May 2010, the number of con- ca de Chile, the Universidad de firmed deaths stood at 521, with 56 Chile, and the Universidad Técni- persons still missing (Ministry of In- Tectonic Setting and ca Federico Santa María. GEER terior, 2010). The earthquake and Geologic Aspects (Geo-engineering Extreme Events tsunami destroyed over 81,000 dwell- Reconnaissance) contributed geo- South-central Chile is a seismically ing units and caused major damage to sciences, geology, and geotechni- active area with a convergence of another 109,000 (Ministry of Housing cal engineering findings. The Tech- nearly 70 mm/yr, almost twice that and Urban Development, 2010). Ac- nical Council on Lifeline Earthquake of the Cascadia subduction zone. cording to unconfirmed estimates, 50 Engineering (TCLEE) contributed a Large-magnitude earthquakes multi-story reinforced concrete build- report based on its reconnaissance struck along the 1500 km-long ings were severely damaged, and of April 10-17. -

200911 Lista De EDS Adheridas SCE Convenio GM-Shell

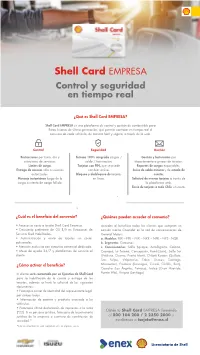

Control y seguridad en tiempo real ¿Qué es Shell Card EMPRESA? Shell Card EMPRESA es una plataforma de control y gestión de combustible para flotas livianas de última generación, que permite controlar en tiempo real el consumo de cada vehículo, de manera fácil y segura, a través de la web. Restricciones por hora, día y Sistema 100% integrado cargas / Gestión y facturación por estaciones de servicios. saldo / facturación. departamento o grupos de tarjetas. Límites de carga. Tarjetas con PIN, que se puede Reportes de cargas exportables. Entrega de accesos sólo a usuarios cambiar online. Aviso de saldo mínimo y de estado de autorizados. Bloqueo y desbloqueo de tarjetas cuenta. Mensaje instantáneo luego de la en línea. Solicitud de nuevas tarjetas a través de carga o intento de carga fallida. la plataforma web. Envío de tarjetas a todo Chile sin costo. ¿Cuál es el beneficio del convenio? ¿Quiénes pueden acceder al convenio? • Acceso sin costo a tarjeta Shell Card Empresa. Acceden al beneficio todos los clientes que compran un • Descuento preferente de -20 $/lt en Estaciones de camión marca Chevrolet en la red de concesionarios de Servicio Shell Habilitadas. General Motors. • Administración y envío de tarjetas sin costos a. Modelos: FRR – FTR – FVR – NKR – NPR – NPS - NQR. adicionales. b. Segmento: Camiones. • Atención exclusiva con ejecutivo comercial dedicado. c. Concesionarios: Salfa (Iquique, Antofagasta, Calama, • Mesa de ayuda 24/7 y plataformas de servicio al Copiapó, La Serena, Concepción, Rondizzoni), Salfa Sur cliente. (Valdivia, Osorno, Puerto Montt, Chiloé) Kovacs (Quillota, San Felipe, Valparaíso, Talca, Linares, Santiago, ¿Cómo activar el beneficio? Movicenter), Frontera (Rancagua, Curicó, Chillán, Buin), Coseche (Los Ángeles, Temuco), Inalco (Gran Avenida, El cliente será contactado por un Ejecutivo de Shell Card Puente Alto), Vivipra (Santiago). -

Chile & Easter Island 9

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over. So go!” TONY WHEELER, COFOUNDER – LONELY PLANET Get the right guides for your trip PAGE PLAN YOUR PLANNING TOOL KIT 2 Photos, itineraries, lists and suggestions YOUR TRIP to help you put together your perfect trip Welcome to Chile ........... 2 Map .................................. 4 20 Top Experiences ....... 6 Welcome to Chile Need to Know ................. 16 If You Like ........................ 18 COUNTRY • The original Month by Month ............. 21 • Comprehensive • AdventurousAdventu Itineraries ........................ 23 (p ) g Artes (Beautiful Art) – says it all. Fan À ne arts can spend the day admiring works at the Museo Nacional de Bel and the Museo de Arte Contemporá housed in the stately Palacio de Bell Chile Outdoors ............... 28 before checking out edgy modern ph and sculpture at the nearby Museo d Meet A LandVisuales. of Along the way, take stayeda brea kintact for so long. The very human Extremes several sidewalk cafes along thequest co bfor development could imperil these pedestrian streets. Palacio detreasures Bellas A sooner than we think. For now, Travel with Children ....... 33 20Preposterously thin and unreasonably Chile guards parts of our planet that re- ong, Chile stretches from the belly of main the most pristine, and they shouldn’t outh America toParque its foot, reaching Nacional from be To missed.r he driest desert delon earth Paine to vast southern TOP lacial À elds. It’s nature on a symphonic La Buena Onda Some rites of passage never los EXPERIENCEScale. Diverse landscapes unfurl over a In Chile, close borders foster intimacy. -

The 2010-2015 Mega Drought in Central Chile: Impacts on Regional Hydroclimate and Vegetation

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., doi:10.5194/hess-2017-191, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discussion started: 26 April 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. The 2010-2015 mega drought in Central Chile: Impacts on regional hydroclimate and vegetation René Garreaud1,2,*, Camila Alvarez-Garreton3,2, Jonathan Barichivich3,2, Juan Pablo Boisier1,2, Duncan 3,2 4,2 3 5 5 Christie , Mauricio Galleguillos , Carlos LeQuesne , James McPhee , Mauricio Zambrano- Bigiarini6,2 1Department of Geophysics, Universidad de Chile, Santiago-Chile 2Center for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), Santiago-Chile 10 3Laboratorio de Dendrocronología y Cambio Global, Instituto de Conservación Biodiversidad y Territorio, Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia-Chile. 4Faculty of Agronomic Sciences, Universidad de Chile, Santiago-Chile 5Department of Civil Engineering, Universidad de Chile, Santiago-Chile 6Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Sciences, Universidad de La Frontera, Temuco-Chile 15 Correspondence to: René. D. Garreaud ([email protected]) 1 Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., doi:10.5194/hess-2017-191, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discussion started: 26 April 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. Abstract. Since 2010 an uninterrupted sequence of dry years, with annual rainfall deficits ranging from 25 to 45%, has prevailed in Central Chile (western South America, 30-38°S). Although intense 1- or 2-year droughts are recurrent in this Mediterranean-like region, the ongoing event stands out because of its longevity and large extent. The extraordinary character of the so-called Central Chile mega drought (MD) was established against century long historical records and a 5 millennial tree-ring reconstruction of regional precipitation. -

VITTORIO QUEIROLO Vittorio Queirolo

1 VITTORIO QUEIROLO Vittorio Queirolo Vittorio Esteban Queirolo Ayala nació el 26 de diciembre de 1963 en Talcahuano, Chile. Biografía Vittorio Esteban Queirolo Ayala nació el 26 de diciembre de 1963 en Talcahuano, Chile. Entre 1986 y 1991 estudió Licenciatura en Arte, Mención Dibujo, en la Universidad Católica de Chile. Al terminar sus estudios regresó a Talcahuano, donde creó su taller de arte en los años noventa y destacó en distintos salones nacionales. A mediados de la década se trasladó a Santiago, ciudad en la que entre 1995 y 2003 realizó clases de pintura. Su trabajo como pintor, que ha sido expuesto en Chile y en el extranjero, aborda diversos temas y estilos como naturalezas muertas, paisajes de corte expresionista y, más recientemente, ha explorado las posibilidades de la abstracción. Además, es socio fundador del Foto Cine Club de la Universidad de Temuco, inaugurado en 1987. El artista reside en Santiago, Chile. Premios, distinciones y concursos 2013 Premio in situ Ricardo Anwanter categoría figurativo y mención honrosa categoría envío, XXX Salón Internacional Valdivia y su Río, Valdivia, Chile. 2011 Segundo lugar, Concurso Nacional Pinceladas Contra Viento y Marea, Municipalidad de Talcahuano, Talcahuano, Chile. 2000 Tercer lugar especialidad Pintura, X versión del Concurso nacional de pintura El color del sur, Santiago, Chile. 1999 Tercer lugar, Segundo Salón Nacional de Pintura Invierno-Primavera, Instituto Chileno Japonés de Cultura, Santiago, Chile. 2 1999 Premio Municipal de Arte, Municipalidad de Talcahuano, Talcahuano, Chile. 1994 Mención Especial In Situ, El color del sur, Puerto Varas, Chile. 1993 Primer Premio en Pintura, Empresas Empremar, Valparaíso, Chile. -

210315 Eds Adheridas Promo Ilusión Copia

SI ERES TRANSPORTISTA GANA UN K M Disponible Estaciones de servicios Shell Card TRANSPORTE Dirección Ciudad Comuna Región Pudeto Bajo 1715 Ancud Ancud X Camino a Renaico N° 062 Angol Angol IX Antonio Rendic 4561 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Caleta Michilla Loteo Quinahue Antofagasta Antofagasta II Pedro Aguirre Cerda 8450 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Panamericana Norte Km. 1354, Sector La Negra Antofagasta Antofagasta II Av. Argentina 1105/Díaz Gana Antofagasta Antofagasta II Balmaceda 2408 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Pedro Aguirre Cerda 10615 Antofagasta Antofagasta II Camino a Carampangue Ruta P 20, Número 159 Arauco Arauco VIII Camino Vecinal S/N, Costado Ruta 160 Km 164 Arauco Arauco VIII Panamericana Norte 3545 Arica Arica XV Av. Gonzalo Cerda 1330/Azola Arica Arica XV Av. Manuel Castillo 2920 Arica Arica XV Ruta 5 Sur Km.470 Monte Águila Cabrero Cabrero VII Balmaceda 4539 Calama Calama II Av. O'Higgins 234 Calama Calama II Av. Los Héroes 707, Calbuco Calbuco Calbuco X Calera de Tango, Paradero 13 Calera de Tango Santiago RM Panamericana Norte Km. 265 1/2 Sector de Huentelauquén Canela Coquimbo IV Av. Presidente Frei S/N° Cañete Cañete VIII Las Majadas S/N Cartagena Cartagena V Panamericana Norte S/N, Ten-Ten Castro Castro X Doctor Meza 1520/Almirante Linch Cauquenes Cauquenes VII Av. Americo Vespucio 2503/General Velásquez Cerrillos Santiago XIII José Joaquín Perez 7327/Huelen Cerro Navia Santiago XIII Panamericana Norte Km. 980 Chañaral Chañaral III Manuel Rodríguez 2175 Chiguayante Concepción VIII Camino a Yungay, Km.4 - Chillán Viejo Chillán Chillán XVI Av. Vicente Mendez 1182 Chillán Chillán XVI Ruta 5 Sur Km. -

Glacier Runoff Variations Since 1955 in the Maipo River Basin

https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2019-233 Preprint. Discussion started: 5 November 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Glacier runoff variations since 1955 in the Maipo River Basin, semiarid Andes of central Chile Álvaro Ayala1,2, David Farías-Barahona3, Matthias Huss1,2,4, Francesca Pellicciotti2,5, James McPhee6,7, Daniel Farinotti1,2 5 1Laboratory of Hydraulics, Hydrology and Glaciology (VAW), ETH Zurich, Zurich, 8093, Switzerland. 2Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research, Birmensdorf, 8903, Switzerland. 3Institut für Geographie, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, 91058, Germany 4Department of Geosciences, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, 1700, Switzerland 5Department of Geography, Northumbria University, Newcastle, NE1 8ST, UK. 10 6Department of Civil Engineering, University of Chile, Santiago, 8370449, Chile. 7Advanced Mining Technology Centre (AMTC), University of Chile, Santiago, 8370451, Chile. Correspondence to: Alvaro Ayala ([email protected]), now at Centre for Advanced Studies in Arid Zones (CEAZA) Abstract (max 250 words). As glaciers adjust their size in response to climate variations, long-term changes in meltwater production can be expected, affecting the local availability of water resources. We investigate glacier runoff in the period 15 1955-2016 in the Maipo River Basin (4 843 km2), semiarid Andes of Chile. The basin contains more than 800 glaciers covering 378 km2 (inventoried in 2000). We model the mass balance and runoff contribution of 26 glaciers with the physically-oriented and fully-distributed TOPKAPI-ETH glacio-hydrological model, and extrapolate the results to the entire basin. TOPKAPI- ETH is run using several glaciological and meteorological datasets, and its results are evaluated against streamflow records, remotely-sensed snow cover and geodetic mass balances for the periods 1955-2000 and 2000-2013. -

The New Zealand Gazette 581

MAY 9] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 581 CHILE CHILE-continued Name. Address. Name. Address. A.E.G., Cia Sudamerikana de Bandera 581, Casilla 9393', De la Ruelle, Jean Marie Santiago. Elecricidad Santiago. Deutsch-Chilenischer Bund Agustinas 975, Santiago. Aachen y Munich, Cia de Seguros Blanco 869, Valparaiso. Deutsche Handelskammer Prat 846, Casilla. 1411,VaIapraiso, Ackerknecht, E. " Esmeralda, 1013, Casilla 1784, and Morande 322, Casilla 4252, Valparaiso. Santiago. Ackermann Lochmann, Luis San Felipe 181, Casilla 227, Deutsche Lufthansa A.G. Bandera 191, Santiago, and .all Puerto Montt. branches in Chile. Agricola Caupolican Ltda. Soc ... Santiago. Deutsche Zeitung fur Chile Merced 673, Santiago. Agricola e Industrial "San Agustinas 975, Santiago, and all Deutscher Sports Verein Margarita 2341, Santiago. Pedro" Ltda., Soc. branches in Chile. Deutscher Verein Salvador Dorroso 1337, Val- Akita Araki, Y osokichi Aldunate 1130, Coquimbo. paraiso. Albingia Versicherungs A.G. Urriola 332, Casilla 2060, Val- Deutscher Verein Plaza Camilo Henriquez 540, Valdivia. paraiso. Deutscher Verein Union Independencia 451, Valdivia. Alemana de Vapores Kosmos, Cia Valparaiso. Diario L'Italia O'Higgins 1266, Valparaiso. Allianz und Stuttgarter Verin Esmeralda 1013, Valparaiso. Diaz Gonzalez, Alicia Madrid 944, Santiago. Versicherungs A.G. Dittmann, Bruno Prat 828, Valparaiso. Amano, Y oshitaro Funda Andalien, Concepcion. Doebbel, Federico Bandera 227, Casilla 3671, San- Anilinas y Productos Quimicos Santiago. tiago. Soc. Ltda., Cia. Generale de Dorbach Bung, Guillermo Colocolo 740, Santiago. Anker von Manstein, Fridleif Constitucion 25, San Francisco Doy Nakadi, Schiochi 21 de Mayo 287, Arica. 1801, and Maria Auxiliadora Dreher Pollitz, Boris Pasaje Matte 81, and San Antonio 998, Santiago. 527, Santiago. Asai,K. Ave. B.