Mapping the Quality of Land for Agriculture in Western Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1992 Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier Randy William Widds University of Regina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Widds, Randy William, "Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier" (1992). Great Plains Quarterly. 649. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/649 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SASKATCHEWAN BOUND MIGRATION TO A NEW CANADIAN FRONTIER RANDY WILLIAM WIDDIS Almost forty years ago, Roland Berthoff used Europeans resident in the United States. Yet the published census to construct a map of En despite these numbers, there has been little de glish Canadian settlement in the United States tailed examination of this and other intracon for the year 1900 (Map 1).1 Migration among tinental movements, as scholars have been this group was generally short distance in na frustrated by their inability to operate beyond ture, yet a closer examination of Berthoff's map the narrowly defined geographical and temporal reveals that considerable numbers of migrants boundaries determined by sources -

GOLD PLACER DEPOSITS of the EASTERN TOWNSHIPS, PART E PROVINCE of QUEBEC, CANADA Department of Mines and Fisheries Honourable ONESIME GAGNON, Minister L.-A

RASM 1935-E(A) GOLD PLACER DEPOSITS OF THE EASTERN TOWNSHIPS, PART E PROVINCE OF QUEBEC, CANADA Department of Mines and Fisheries Honourable ONESIME GAGNON, Minister L.-A. RICHARD. Deputy-Minister BUREAU OF MINES A.-0. DUFRESNE, Director ANNUAL REPORT of the QUEBEC BUREAU OF MINES for the year 1935 JOHN A. DRESSER, Directing Geologist PART E Gold Placer Deposits of the Eastern Townships by H. W. McGerrigle QUEBEC REDEMPTI PARADIS PRINTER TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING 1936 PROVINCE OF QUEBEC, CANADA Department of Mines and Fisheries Honourable ONESIME GAGNON. Minister L.-A. RICHARD. Deputy-Minister BUREAU OF MINES A.-O. DUFRESNE. Director ANNUAL REPORT of the QUEBEC BUREAU OF MINES for the year 1935 JOHN A. DRESSER, Directing Geologist PART E Gold Placer Deposits of the Eastern Townships by H. W. MeGerrigle QUEBEe RÉDEMPTI PARADIS • PRINTER TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING 1936 GOLD PLACER DEPOSITS OF THE EASTERN TOWNSHIPS by H. W. McGerrigle TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 5 Scope of report and method of work 5 Acknowledgments 6 Summary 6 Previous work . 7 Bibliography 9 DESCRIPTION OF PLACER LOCALITIES 11 Ascot township 11 Felton brook 12 Grass Island brook . 13 Auckland township. 18 Bury township .. 19 Ditton area . 20 General 20 Summary of topography and geology . 20 Table of formations 21 IIistory of development and production 21 Dudswell township . 23 Hatley township . 23 Horton township. 24 Ireland township. 25 Lamhton township . 26 Leeds township . 29 Magog township . 29 Orford township . 29 Shipton township 31 Moe and adjacent rivers 33 Moe river . 33 Victoria river 36 Stoke Mountain area . -

Introductionntroduction

CCHAPTERHAPTER 1:1: IINTRODUCTIONNTRODUCTION In This Chapter: Historical Setting - History & Memories Location in the County & Region - Location & Description, Municipal Boundaries Regional Influences on the Township - Accessibility, Urban Development, Transportation, Recreation and Cultural Facilities PORT HURON TOWNSHIP MASTER PLAN INTRODUCTION The information presented here is a combination of input from citizens and elected and appointed officials, as well as Township Planning Commission members and staff, along with the assistance and guidance of the St. Clair County Planning Commission. It contains statistical data and information, both past and present, that can give some insight for our future. While we cannot definitively project future development, we can try to help determine efficient and effective ways of managing and shaping the way our Township develops. In concert with that thought, this plan also includes a chapter on a Vision for the Township which includes both goals and objectives. This can help us focus on what we would like development to look like when it comes, and to give direction to developers on the expectations we have as a community. Knowing that these goals and objectives have been developed by our citizens gives them guidance as to what is desirable and marketable to our residents and therefore profitable to them. While many master plans contain an overwhelming amount of statistical information, we hope to provide a fair amount of usable information in the form of maps, charts and tables that demonstrate logical and historical reasons and trends for what has taken place in the Township and how we can benefit from that in our future. -

Largely Granted to and Settled by United Empire Loyalists Under Who Married Reuben B

376 37T largely granted to and settled by United Empire Loyalists under who married Reuben B. Scott, and settled at Colborne. Their Captain Michael Grass. children and grandchildren are now quite widely scattered, some The second township, called Ernesttown, was settled mainly of them being in the United States, others in Toronto, while a few by the officers and soldiers of Sir John Johnson's regiment, also are in the neighborhood of Colborne and the Bay district. His known as the King's New York Eoyal Eangers. The third town- son, James P. Scott, married M. Agatha Ives; they reside in ship, or Fredericksburg, was granted mainly to the soldiers of a Toronto and have four children, namely, Susannah Ives, Luella particular regiment while the fourth township, or Adolphus- Isabel, Agatha J. and Helen A. The two last named are twins, town, was granted to and settled by some of the best people who born September 17, 1904. * made up the United Empire Loyalist movement. They had served in the Eevolutionary War, and they were nearly all of them peo- LIEUT. JOHN HUYCK. ple of property, and their average intelligence and education was THE CHILDREN AND GRANDCHILDREN: remarkably high. Hence we find that while Adolphustown is the I. John Huyck, m. Jemima Clapp; set. Adolphustown. Issue: smallest township in Ontario in area, it has occupied for many (1) John, (2) Benjamin, (3) William H., (4) Burger, (5) years a commanding place in the province, and from its founda- Thomas, (6) Henry, (7) Jane, (8) Anne, (9) Phoebe, and tion to this time has contributed many men to public life. -

Stanley Township

Municipal Inventory of Cultural Heritage Properties - Stanley Township Inventory of Designated and Potential Heritage Properties Municipality of Bluewater, Ontario (Comprised of the former Geographical Townships of Hay and Stanley and the villages of Bayfield, Hensall and Zurich) Written by Jodi Jerome for the Bluewater Heritage Committee, 2014 Introduction When the Municipality of Bluewater amalgamated the townships and hamlets of Hay and Stanley and the villages of Bayfield, Hensall and Zurich in 2001, the result was a municipality rich in built heritage, culture and tradition. The Bluewater Heritage Committee has enlarged the work started by the earlier Bayfield Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee (LACAC) and the Bayfield Historical Society. The plaquing program that began with the Bayfield LACAC has been continued by the Bluewater Heritage Committee, who have enlarged the original plaquing program recognizing, not designating, sites of significance throughout the municipality. At present, there are no properties in the Stanley Township area of the Municipality of Bluewater that have been designated. There are century farms recognized by the Junior Farmers and properties recognized by historical plaques from the Bluewater Heritage Committee, which relies on members of the public volunteering their home and/or farm for a plaque and splitting the cost for the plaque. Bluewater Heritage Committee Goals: -expand the recognition of potential heritage resources within the municipality -locate and publicly recognize the rich -

Irish John Willson United Empire Loyalist Family Fonds 1772-1978 (Non-Inclusive)

Irish John Willson United Empire Loyalist Family Fonds 1772-1978 (non-inclusive) RG 169-1 Brock University Archives Creator: Maclean Family members Extent: 1.67m textual records - 2 ½ cartons, 1 large format storage box 78 photographs Abstract: This fonds contains materials relating to the family of Irish John Willson. The bulk of the materials contains correspondence, financial records; including deeds, indentures, insurance papers. The collection also contains photographs as well as personal and military ephemera and some items of realia. Materials: Typed and handwritten correspondence, photographs, ephemera, realia, reciepts, deeds, grants, and certificates. Repository: Brock University Archives Processed by: Jen Goul Last updated: November 2007 ______________________________________________________________________________ Terms of Use: The Irish John Willson United Empire Loyalist Family Fonds is open for research. Use Restrictions: Current copyright applies. In some instances, researchers must obtain the written permission of the holder(s) of copyright and the Brock University Archives before publishing quotations from materials in the collection. Most papers may be copied in accordance with the Library's usual procedures unless otherwise specified. Preferred Citation: RG 169, Irish John Willson United Empire Loyalist Family Fonds , 1772- 1978, n.d., Brock University Archives. Acquisition Info.: This fonds was donated by Alexis MacLean Newton on March 9, 2006; on behalf of herself, and the estate of Sheila Jean MacLean. ______________________________________________________________________________ History: John Willson first came to Upper Canada along with his friend Nathaniel Pettit in the late 1700s. They both moved with their families from New Jersey where they had both been imprisioned for not siding with the rebels and maintaining Loyalist allegiences. Pettit arrived with his four daughters, leaving his son behind. -

They Planted Well: New England Planters in Maritime Canada

They Planted Well: New England Planters in Maritime Canada. PLACES Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia, 9, 10, 12 Amherst Township, Nova Scotia, 124 Amherst, Nova Scotia, 38, 39, 304, 316 Andover, Maryland 65 Annapolis River, Nova Scotia, 22 Annapolis Township, Nova Scotia, 23, 122-123 Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia, 10, 14-15, 107, 178 Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, 20, 24-26, 28-29, 155, 258 Annapolis Gut, Nova Scotia, 43 Annapolis Basin, Nova Scotia, 25 Annapolis-Royal (Port Royal-Annapolis), 36, 46, 103, 244, 251, 298 Atwell House, King's County, Nova Scotia, 253, 258-259 Aulac River, New Brunswick, 38 Avon River, Nova Scotia, 21, 27 Baie Verte, Fort, (Fort Lawrence) New Brunswick, 38 Barrington Township, Nova Scotia, 124, 168, 299, 315, Beaubassin, New Brunswick (Cumberland Basin), 36 Beausejour, Fort, (Fort Cumberland) New Brunswick, 17, 22, 36-37, 45, 154, 264, 277, 281 Beaver River, Nova Scotia, 197 Bedford Basin, Nova Scotia, 100 Belleisle, Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, 313 Biggs House, Gaspreau, Nova Scotia, 244-245 Blomidon, Cape, Nova Scotia, 21, 27 Boston, Massachusetts, 18, 30-31, 50, 66, 69, 76, 78, 81-82, 84, 86, 89, 99, 121, 141, 172, 176, 215, 265 Boudreau's Bank, (Starr's Point) Nova Scotia, 27 Bridgetown, Nova Scotia, 196, 316 Buckram (Ship), 48 Bucks Harbor, Maine, 174 Burton, New Brunswick, 33 Calkin House, Kings County, 250, 252, 259 Camphill (Rout), 43-45, 48, 52 Canning, Nova Scotia, 236, 240 Canso, Nova Scotia, 23 Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, 40, 114, 119, 134, 138, 140, 143-144 2 Cape Cod-Style House, 223 -

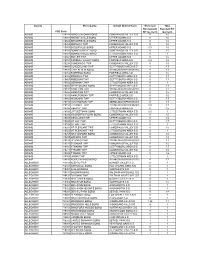

County PSD Code Municipality School District Name

County Municipality School District Name Municipal Total Nonresident Resident EIT PSD Code EIT (percent) (percent) ADAMS 010201 ABBOTTSTOWN BORO CONEWAGO VALLEY S D 0 1.5 ADAMS 010601 ARENDTSVILLE BORO UPPER ADAMS S D 0 1.6 ADAMS 010602 BENDERSVILLE BORO UPPER ADAMS S D 0 1.6 ADAMS 010202 BERWICK TWP CONEWAGO VALLEY S D 0 1.5 ADAMS 010603 BIGLERVILLE BORO UPPER ADAMS S D 0.5 1.6 ADAMS 010203 BONNEAUVILLE BORO CONEWAGO VALLEY S D 0 1.5 ADAMS 010501 BONNEAUVILLE BORO LITTLESTOWN AREA S D 0 1 ADAMS 010604 BUTLER TWP UPPER ADAMS S D 0 1.6 ADAMS 010301 CARROLL VALLEY BORO FAIRFIELD AREA S D 0.5 1.5 ADAMS 010204 CONEWAGO TWP CONEWAGO VALLEY S D 0 1.5 ADAMS 010401 CUMBERLAND TWP GETTYSBURG AREA S D 1 1.7 ADAMS 010101 EAST BERLIN BORO BERMUDIAN SPRINGS S D 0 1.7 ADAMS 010302 FAIRFIELD BORO FAIRFIELD AREA S D 0 1.5 ADAMS 010402 FRANKLIN TWP GETTYSBURG AREA S D 0 1.7 ADAMS 010403 FREEDOM TWP GETTYSBURG AREA S D 0 1.7 ADAMS 010502 GERMANY TWP LITTLESTOWN AREA S D 0 1 ADAMS 010404 GETTYSBURG BORO GETTYSBURG AREA S D 0 1.7 ADAMS 010102 HAMILTON TWP BERMUDIAN SPRINGS S D 0 1.7 ADAMS 010205 HAMILTON TWP CONEWAGO VALLEY S D 0 1.5 ADAMS 010303 HAMILTONBAN TWP FAIRFIELD AREA S D 0 1.5 ADAMS 010405 HIGHLAND TWP GETTYSBURG AREA S D 0 1.7 ADAMS 010103 HUNTINGTON TWP BERMUDIAN SPRINGS S D 0 1.7 ADAMS 010104 LATIMORE TWP BERMUDIAN SPRINGS S D 0.5 1.7 ADAMS 010304 LIBERTY TWP FAIRFIELD AREA S D 0 1.5 ADAMS 010503 LITTLESTOWN BORO LITTLESTOWN AREA S D 0.5 1 ADAMS 010206 MCSHERRYSTOWN BORO CONEWAGO VALLEY S D 0 1.5 ADAMS 010605 MENALLEN TWP UPPER ADAMS S D 0 1.6 -

Saskatchewan Provinical Standard System of Rural Addressing

300 – 10 Research Drive Regina, Canada S4S 7J7 Phone Ask ISC at 1-866-275-4721 www.isc .ca Saskatchewan Provincial Standard System of Rural Addressing Adopted by Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities (SARM) at the 2005 mid-term convention under the Rural Municipal Signing System Resolution No. 7-05M Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Required Attributes of an Addressing System ........................................................................... 1 Standard Address System ......................................................................................................... 2 Road Name................................................................................................................................... 2 Access Numbers...................................................................................................................................2 Unit Numbers.....................................................................................................................................3 Road Signage................................................................................................................................. 3 Figures ........................................................................................................................................ -

The Loyalists Preschool/Elementary Area

HOME ABOUT LEARN SERVICES AND PUBLICATIONS CONTACT US HELP SITE MAP FRANÇAIS Search Username •••••••• You are in the Students - You Are Here: Elementary Curriculum>Elementary Social Sciences>Cycle 3>The Loyalists Preschool/Elementary area. (Click to change area.) Elementary Curriculum Preschool Education Arts Education Personal Development Languages Elementary Social Sciences Program Information About the Project Supplementary Resources Cycle 1 During and following the American Revolution (1775-1783), an estimated 50,000 American colonists who Cycle 2 remained loyal to the British Crown sought refuge in the remaining provinces of British North America, now Cycle 3 The Loyalists part of Canada. While most of the Loyalists who came to present-day Quebec eventually relocated to what Overview (after 1791) became Upper Canada, a significant number remained in what became Lower Canada, where Curricular Fit they settled in various areas, particularly in the Eastern Townships and the south coast of Gaspé, and Background made notable contributions to the development of the Province as a whole. Their descendants are many information and include both English-speaking and French-speaking Quebecers. Learning Activities Materials The Loyalists website was designed for Elementary Cycle 2 and 3 Geography, History and Citizenship Additional Resources Kids' Zone Education. We have provided resources to help you guide your students as they travel through time 1820s exploring the lives of Loyalists who left the Thirteen Colonies and settled in present-day Canada from 1776- Community Info. 1792. For a detailed description of the site, see the Overview section. For more information on links to the Math, Science & Technology Social Sciences program, see the Curricular Fit section. -

The United Empire Loyalists' Association Of

The United Empire Loyalists’ Association of Canada UE CERTIFICATE APPLICATION FORM — July April 2018 Computer Fillable Form INSTRUCTIONS *NB: some details may vary somewhat between the PDF and the WORD versions. 1) ALWAYS use page 7 for the Loyalist Generation. 2) READ THROUGH THE ENTIRE FORM, and PLAN out which pages YOU will use. You have a choice between using page 6 (which has space for 2 half-page generations) or using pages 6A and 6B which allow MORE space should you have more information that page 6 allows. Yes, you can use ONE half-page generation on page 6 and use either 6A or 6B as suitable. READ the instruction CUES under the fields that help you learn what information goes where. 3) MERGE or SUBSEQUENT FAMILY APPLICATION: This version allows you to change the generation numbers on an existing completed application. Therefore, if you have a family member, even a cousin, who wishes to apply later, either using a ‘merge’ or even after the 12 months of merge eligibility has passed, one need not re-enter all the information. Simply open & save a renamed copy of the completed form. THEN change the generation numbers on pages 3 to 7 as needed to suit the new applicant. Create a new page 1 and 2 from a NEW BLANK form for each new applicant. In the PRINT function, you can select WHICH PAGES to print. Print ONLY the ones that you need and have completed. AND with your Proof pages, a similar renumbering will be needed. Having them saved in a word document, in the correct order, and with the citations will allow ease of again changing the numbering and a submission can be completed without much difficulty. -

Warwick Township Demographic and Industrial Profile Mellor Murray Consulting August 28, 2017

Warwick Township Demographic and Industrial Profile Mellor Murray Consulting August 28, 2017 Contents Warwick: Summary Demographic Profile ..................................................................................................... 3 Warwick Industrial Profile: Introduction ........................................................................................................ 5 Initial Observations ................................................................................................................................... 5 Primary Industries ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Construction, Manufacturing, Trade and Transportation .......................................................................... 7 Information, Finance and Professional Services ...................................................................................... 8 Education, Health Care and Public Administration ................................................................................... 8 Tourism ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Other Sectors ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Appendix .....................................................................................................................................................