Sustainability of Reusable Packaging–Current Situation and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Packing and Crating Basics C2C Care Webinar to Begin With

Packing and Crating Basics C2C Care Webinar To begin with... ● Determine the needs of your object ○ What is your object made out of? ○ How will your crate be used? ■ Storage? ■ Traveling? ● How many times will the crate travel? ○ Single venue vs. multi-venue Storage vs. Traveling Crates ● There is a difference between crates for storage and crates for transit ● Different materials will be used for storage vs. transit ● Types of foam: ○ Thermal insulating foams for transit ■ U-foam ■ Esterfoam ■ Polystyrene Extruded foam ○ Shock absorbing foams for transit and storage ■ Ethafoam (various densities) ■ Volara Storage Concerns ● Off-gassing inside the storage crate ○ Avoid using Esterfoam, U-foam, and Polystyrene foams. ■ Objects should not be stored in closed crates with these foams for more than 90 days. ○ Be aware of the materials the object will be contact with. ○ Be aware of the composition of the object itself. ● Object should be easy to access and identify Transit Concerns ● Vibration and shock ○ Use an appropriate amount and type of foam ● Changes in temperature and climate ○ Line crates with thermal insulating foam such as U-foam, Esterfoam, or Polystyrene Extruded foam ● Handling ○ Crate should have clear stencils, skids, and handles to encourage safe handling ● Ease of packing/unpacking ○ Clear packing/unpacking instructions/diagrams Flatworks Common packing solutions for flatworks: ● Trays ○ Usually for framed works ○ allows multiple objects to be packed in the same crate ● Travel frames ○ For unframed canvases, or objects that -

What Is Plastic Reusable Packaging?

Sustainability Advantages of Reusable Containers What is plastic reusable packaging? Plastic reusable packaging products are used to move, store and distribute product within a single operation or entire supply chain. From raw material to finished goods, plastic reusable packaging safely and efficiently moves material/product along different points of the supply chain and ultimately to its destination. It is ideal for multiple trip applications in a closed-loop environment or well-managed supply chain. It can also be used effectively in a managed open-loop system, with reverse logistics in place to return empty containers or pallets for re-use or replenishment. Products can include: • Hand-held containers, bins, boxes or totes • Pallets, slip sheets, top frames and top caps • Divider sheets • Bulk containers, bins, boxes or totes • Protective interior dunnage (custom) • Storage containers and metal systems • Custom designed and engineered packaging By design, plastic reusable packaging products offer durable, rigid construction; contoured surfaces; easy-to-grasp handles; high levels of recyclability and vast identification options. These dimensionally consistent containers and pallets are easy to handle and interface effortlessly with all types of high-speed automated equipment. In fact, some products are specially designed to be "hands-free" and solely handled by robots or conveyors. Plastic packaging has no nails or loose corrugated flaps to halt a high-speed system. And, in high-volume industries, hundreds of thousands of dollars are lost when an automated system is stopped. Whether shipping plastic bottles to a soft drink bottler for filling; trim parts to an automotive manufacturer; electronic components to a computer manufacturer or consumer goods to the mass retailer, plastic reusable containers and pallets will help move product faster, better, safer and more cost effectively. -

Structures and Exterior Envelope

Integration: Structure and Envelope Integrated Building Systems Part I: Integration Principles Part II: Structure and the Exterior Envelope Part III: Integration Case Studies 4.405Building Systems Building Systems: Definitions 1. Foundation/Subgrade (SITE) 2. Superstructure (STRUCTURE) Daly, Genik: Valley Center, CA, 2000. 3. Exterior Envelope (SKIN) 4. Interior Partitions (SPACE PLAN) 5. Mechanical Systems (SERVICES) 6. Furnishings (STUFF) Stuff Space Plan Services Structure Sources: Brand, Howard, Skin How Buildings Learn. Site Also see Turner, Gregory, Construction Economics and Building Design Bensonwood Timber Frame: 1996. Image by MIT OCW. 4.405Building Systems Building Systems: Definitions 1. Foundation/Subgrade (SITE) 2. Superstructure (STRUCTURE) 3. Exterior Envelope (SKIN) 4. Interior Partitions (SPACE PLAN) 5. Mechanical Systems (SERVICES) 6. Furnishings (STUFF) Rush specifies only four systems; • Structure • Envelope • Interior • Mechanical Source: Rush, Richard, The Building Systems Integration Handbook Curtainwall and raised floor construction. Image by MIT OCW. Integration Levels Definitions 1. Remote: systems are Remote physically separated from one another but yet still coordinated functionally Touching 2. Touching: One system rests on another Connected 3. Connected: one system is mechanically fastened and dependent on another Meshed 4. Meshed: systems occupy the same space Unified 5. Unified: systems share the same physical elements Five Levels of Integration Image by MIT OCW. Image by MIT OCW. Performance Mandates Roof Assembly: Performance is, generally, the Roof structure and measurement of achievement structural deck (S) Roofing (E) E against intention. Ceiling (I) Lighting (MI) Roof Assembly S Wall Assembly: 1. Spatial Performance Wall structure (the support plus any lateral bracing, shear panels, I MI 2. Thermal Performance or sheathing) (S) I Exterior wall covering (EI) 3. -

Paper 101 with Courtney Cerruti

Paper 101 with Courtney Cerruti Chapter 1 - Paper 101 Paper 101 (pop drum music) - Paper is one of those medium's that really is so versatile, and can be used for so many projects. I love to make a-million-and-one different things out of paper. Anywhere from book crafts, to paper crafts, things like making cards, doing collages, or even something like making paper flowers. And for all of those projects, I would use a different weight of paper. And it's really helpful to understand a little bit more about paper when you start to work with it. How to find grain and what projects should be used with which types of paper. If you're familiar with the concept that fabric has a grain, paper also has a grain. And that just indicates which way the fibers of the paper, when it's made, are running. If they're predominantly running vertically or horizontally. So, we do this things called the "bounce test," which always you to just fold the paper in one direction, and just gently bounce it to see how much resistance you have, and then you would turn it the opposite direction, and do the same thing. And you can see, that I really press this down. So, that means, that my grain is going parallel to where I'm creating this little fold. So, my grain runs this way. If we go back to that other direction, we can see how hard that is to press it down. And that's against the grain. -

Using Plastic Reusable Packaging to Support Your Lean Operation

Lean Packaging: Using Plastic Reusable Packaging to Support Your Lean Operation Copyright ã2004 ORBIS Corporation Executive Overview Today, more than 33% of US companies recognize the need for a lean philosophy to gain optimization in their operations and entire supply chain. Very simply….the lean philosophy emphasizes total system efficiency, continual improvement and value-added activity, to reduce costs. 1 This can be achieved in three ways: § The aggressive elimination of waste § Improved productive flow of material/product § Highly optimized inventory management According to the March 2001 issue of Modern Materials Handling, “Businesses succeed or fail based on their supply chain performance, therefore, the scope of lean thinking must encompass every aspect of every job within a company, including factory operations, engineering, project management, transportation and finance.” 2 And this includes packaging. According to Ford Motor Company, plastic reusable packaging drives lean production by facilitating the tremendous benefits. It opens the door to better scheduling, smaller batches and inventories, faster response to schedule changes and smaller, more frequent deliveries leading to the success of their "Synchronous Material Flow." It facilitates improved layouts and processes and provides a cleaner, safer, more ergonomic workplace. The net effect drives costs down. 3 The concepts behind lean production are not industry-specific. Whether shipping plastic bottles to a soft drink bottler for filling; trim parts to an automotive manufacturer; electronic components to a computer manufacturer or consumer goods to the mass retailer, plastic reusable packaging will help move product faster, better, safer and more cost effectively. While lean production seems is prevalent in the automotive industry, plenty of other leading industries have adopted lean philosophies, including: beverage, electronics, aerospace and pharmaceutical. -

Roundtable Sustainability Series: the Packaging Industry

Executive Insights Roundtable Sustainability Series: The Packaging Industry We recently held an in-depth conversation about Recycled packaging can involve different substrates, or materials, sustainability’s impact on packaging with three such as tin, recycled plastics, recycled paperboard and wood chips. Recycled packaging is the most prevalent sustainable leaders in L.E.K. Consulting’s Paper & Packaging packaging product. Over the years, the quality of recycled practice: Thilo Henkes, Managing Director and packaging products has improved so much that some recycled packaging can be used in contact with food. However, we have practice head; Jeff Cloetingh, Managing Director; yet to see a recycled or biodegradable packaging product that and Rory Murphy, Principal. Excerpts from our can be used in medical applications that require sterility. wide-ranging discussion can be found below. Reusable packaging has been coming into vogue over the past few years. It involves a reusable container — for example, a How do you define sustainability in packaging? metal container that you can bring back to the store and get Thilo Henkes: Sustainability is a pressing topic in packaging; it’s a refilled. You see it mostly with food — Nestle is using it for ice growing segment of the packaging sector that is experiencing a lot cream — and some personal care applications such as shampoos of innovation as consumers increasingly focus on how sustainable and body creams. the packaging is for the products they purchase. Brands and what they stand for are embodied in their packaging, and a lot What is defined as sustainable packaging? of packaging gets discarded, so brands are increasingly giving In the market today there are three types of substrates the sustainability of their packaging attention as some consumer that fall under the definition of sustainable: biodegradable segments are making brand selection decisions based on it. -

Food Packaging Technology

FOOD PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY Edited by RICHARD COLES Consultant in Food Packaging, London DEREK MCDOWELL Head of Supply and Packaging Division Loughry College, Northern Ireland and MARK J. KIRWAN Consultant in Packaging Technology London Blackwell Publishing © 2003 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered Editorial Offices: trademarks, and are used only for identification 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ and explanation, without intent to infringe. Tel: +44 (0) 1865 776868 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK First published 2003 Tel: +44 (0) 1865 791100 Blackwell Munksgaard, 1 Rosenørns Allè, Library of Congress Cataloging in P.O. Box 227, DK-1502 Copenhagen V, Publication Data Denmark A catalog record for this title is available Tel: +45 77 33 33 33 from the Library of Congress Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, British Library Cataloguing in Victoria 3053, Australia Publication Data Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 A catalogue record for this title is available Blackwell Publishing, 10 rue Casimir from the British Library Delavigne, 75006 Paris, France ISBN 1–84127–221–3 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 10 Originated as Sheffield Academic Press Published in the USA and Canada (only) by Set in 10.5/12pt Times CRC Press LLC by Integra Software Services Pvt Ltd, 2000 Corporate Blvd., N.W. Pondicherry, India Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA Printed and bound in Great Britain, Orders from the USA and Canada (only) to using acid-free paper by CRC Press LLC MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall USA and Canada only: For further information on ISBN 0–8493–9788–X Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: The right of the Author to be identified as the www.blackwellpublishing.com Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Bringing Reusable Packaging Systems to Life Lessons Learned from Testing Reusable Cups Table of Contents

Bringing Reusable Packaging Systems to Life Lessons Learned from Testing Reusable Cups Table of Contents Introduction SECTION 1 SECTION 4 Setting the Scene Experimentation in Action — Lessons Learned — Reuse Model Insights Piloting Innovative Reusable Top Insights for Reuse How It Works Cup Systems Models SECTION 2 SECTION 5 The Journey of a Reusable What’s Next? — Building the Cup — A Multi-Stage Journey Future for Reuse Models Customer Awareness Sign-up Point-of-Sale SECTION 6 Drink Preparation Point-of-Handoff Appendix Point-of-Return Terms to Know Washing & Sanitizing Citations Pick-up & Delivery Acknowledgements B L E Inventory A T O F SECTION 3 Bringing Reusable Packaging C Systems to Life – Critical O Inputs & Considerations for N Scale S T T Engage Diverse Stakeholders E N Make Sustainable Material Choices Select the Perfect Spot Choose the Right Payment Model Optimize Health & Safety Protocols Measure Impact and Success Bringing Reusable Packaging Systems to Life 2 Dear Reader, If you visualize the current journey of most products and packaging in our economy, including the single-use cup, it looks like a straight line that starts with extracting finite raw materials and ends at the landfill. fter decades of relying on this food, are accelerating the growth of reuse The key to success for reuse models is seemingly convenient linear models. Over the last few years, we’ve seen continually testing, honing and refining them. Asystem, its long hidden costs in innovative companies explore and harness And assessing the environmental impact of terms of economic and environmental groundbreaking reusable packaging and reusable packaging is paramount during this consequences have become clear, bringing refill models, such as Algramo piloting phase of experimentation — we must ensure we us to a tipping point that necessitates a their “smart dispensing” reuse model with don’t introduce new unintended consequences better way forward — one that considers companies like Nestlé and Unilever, among when replacing one system with another. -

Using Reusable Packaging to Optimize Your

60 Why Reusables? Using Plastic Reusable Packaging to Optimize Your Supply Chain Copyright ã2004 ORBIS Corporation Executive Overview Today’s supply chains are becoming more and more complex. With shorter product life cycles and rising customer demands, as well as the increasing spread of distribution, manufacturing, sourcing and engineering functions around the world, companies are seeking to successfully manage their supply chain, for improved profitability. 1 The good news: Those who have mastered supply chain excellence can experience up to 73% greater profit margins than other companies. 2 Plastic reusable packaging improves the flow of product all along the supply chain in many industries, to reduce total costs and achieve sustained optimization. Whether shipping plastic bottles to a soft drink bottler for filling; trim parts to an automotive manufacturer; electronic components to a computer manufacturer or consumer goods to the mass retailer, plastic reusable containers and pallets will help move product faster, better, safer and more cost effectively. Plastic reusable packaging is integrated in a single operation or entire supply chain to take the place of single-use corrugated shipping and storage boxes and limited-use wood pallets. Users experience a rapid return on their packaging investment…many times in 6-18 months or less. U.S. firms will spend on average $4.8 billion a year through 2008 to tune their supply network processes. 3 In this paper we will look closely at a basic supply chain model and address how companies, regardless -

The Shifting Beverage Landscape

IBDEA 2016 The Shifting Beverage Landscape March 19, 2016 Beverage Marketing Capabilities Beverage Marketing Corporation utilizes an integrated model for providing information, analysis and advice to beverage industry clients Unique Beverage Industry Expertise for Providing “Added-Value” to Selected Clients Cutting Edge Insights: New Age Emergence, Multiple Beverage Competition, Specialty Beer Opportunity, Bottled Water Dominance, Hyper-Category Competition, Micro-Marketing Age -2- Copyright © 2016 Beverage Marketing Corp. The Shifting Beverage Landscape Agenda I. Market Overview II. Key Trends III. Category Updates IV. Projections -3- Copyright © 2016 Beverage Marketing Corp. The Shifting Beverage Landscape State of the Industry – The Good and the Bad Beverage Headlines Liquid refreshment beverage market grows for second consecutive year in 2015 after flat performance in 2013 Carbonated soft drinks experience another modest sales decline in 2015 Bottled water continues its solid growth trend led by single-serve water segment Niche categories continue to outperform traditional mass-market categories Wine and spirits lead alcohol growth in 2015, and beer experiences slower growth performance -4- Copyright © 2016 Beverage Marketing Corp. The Shifting Beverage Landscape The economy continues to move in a positive direction with improved GDP growth and lower unemployment, but improvement has been slow due to severity of the recession Quarterly GDP Change Unemployment Rate 2010 – 2015 2000 – 2015 10% 9.6% 9.3% 9.0% 8% 8.1% 7.4% 6.2% 6% 6.0% 5.8% 5.8% 5.5% 5.1% 5.3% 4.7% 4.6% 4.6% 4% 4.0% 2% 0% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 '00 '01 '02 '03 '04 '05 '06 '07 '08 '09 '10 '11 '12 '13 '14 '15 Source: Beverage Marketing Corporation; Bureau of Economic Analysis, Department of Commerce, Department of Labor -5- Copyright © 2016 Beverage Marketing Corp. -

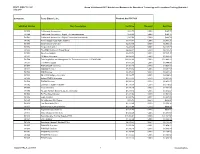

Festo Didactic, Inc. SKU/Part Number Item Description List Price Discount

FESTO DIDACTIC, INC. Group 38224-Award 23077 Materials and Equipment for Educational Technology and Occupational Training (Statewide) July 2019 Contractor: Festo Didactic, Inc. Contract No: PC67815 SKU/Part Number Item Description List Price Discount Net Price 581539 Cables and Accessories $258.71 5.00% $245.77 581540 Cables and Accessories - Digital Telecommunications $574.89 5.00% $546.15 581541 Cables and Accessories - Digital Communications Add-On $467.09 5.00% $443.74 581542 Power Supply / Dual Audio Amplifier $3,018.17 5.00% $2,867.26 581549 Dual Function Generator $2,903.19 5.00% $2,758.03 581552 Frequency Counter $2,249.25 5.00% $2,136.79 581555 True RMS Voltmeter / Power Meter $2,292.37 5.00% $2,177.75 581558 Spectrum Analyzer $8,407.76 5.00% $7,987.37 581561 RF/Noise Generator $4,024.23 5.00% $3,823.02 581564 Data Acquisition and Management for Telecommunications (LVDAM-COM) $23,642.33 5.00% $22,460.21 581571 TTS Power Supply $1,415.66 5.00% $1,344.88 581574 AM/DSB/SSB Generator $4,804.25 5.00% $4,564.04 581577 AM/DSB Receiver $3,370.14 5.00% $3,201.63 581580 SSB Receiver $3,370.14 5.00% $3,201.63 581583 Direct FM Multiplex Generator $5,162.77 5.00% $4,904.63 581586 Indirect FM/PM Generator $4,517.43 5.00% $4,291.56 581589 FM/PM Receiver $6,740.28 5.00% $6,403.27 581592 Enclosure / Supply Regulator $1,178.53 5.00% $1,119.60 581593 Clock Generator $2,486.40 5.00% $2,362.08 581596 Pseudo-Random Binary Sequence Generator $3,233.76 5.00% $3,072.07 581599 Bit Error Rate Indicator $1,624.06 5.00% $1,542.86 581602 Logic Analyzer $1,997.74 -

KMR Catalogue 2021

The partner of craftsmen Catalogue 2021 New! www.kmr-group.eu Company history Welcome to KMR! 1914 Karl Mathias Reich founded the business with 5 employees and started manufacturing wire and equipment that uses wire. 1925 The first stationary carpentry equipment. 1960s New creations like the first portable pneumatic nailers. 2000 Foundation of the Karl M. Reich GmbH production and distribution company. 2013 The Karl M. Reich Verbindungstechnik brand was taken over by the German BeA group. 2016 The products bear the initials of the founder Karl Mathias Reich: KMR. 2018 Introduction of gas nailers into the product range 2020 Relaunch of the KMR homepage, state-of-the-art technique: modern, quick, user-friendly and all information on tools and fasteners at your disposal any time and anywhere! 2021 Introduction of the new KMR 3-in-1 Multi tool AC/90-942C. The unique nailing tool for 3 different nail collation types. KMR – The partner of craftsmen All information concerning our tools and fasteners can be retrieved as of now on mobile devices at any time. Our product information is at your disposal exactly when you need it - in the office, on the construction site, in the factory or when visiting a client. www.kmr-group.eu gives you quick and easy all information on our product range: Our tools for professionals and fasteners in different materials and dimensions. Furthermore you will find all technical details on our tools, helpful application hints for your projects as well as a huge download area. The download area contains all important documents and declarations of performance (DoPs), CE-label, ETA approvals, as well as manuals - all these documents are available online at any time.