African Workers Strike Against Apartheid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIFE and WORK in the BANANA FINCAS of the NORTH COAST of HONDURAS, 1944-1957 a Dissertation

CAMPEÑAS, CAMPEÑOS Y COMPAÑEROS: LIFE AND WORK IN THE BANANA FINCAS OF THE NORTH COAST OF HONDURAS, 1944-1957 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda January 2011 © 2011 Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda CAMPEÑAS Y CAMPEÑOS: LIFE AND WORK IN THE BANANA FINCAS OF THE NORTH COAST OF HONDURAS, 1944-1957 Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 On May 1st, 1954 banana workers on the North Coast of Honduras brought the regional economy to a standstill in the biggest labor strike ever to influence Honduras, which invigorated the labor movement and reverberated throughout the country. This dissertation examines the experiences of campeños and campeñas, men and women who lived and worked in the banana fincas (plantations) of the Tela Railroad Company, a subsidiary of the United Fruit Company, and the Standard Fruit Company in the period leading up to the strike of 1954. It describes the lives, work, and relationships of agricultural workers in the North Coast during the period, traces the development of the labor movement, and explores the formation of a banana worker identity and culture that influenced labor and politics at the national level. This study focuses on the years 1944-1957, a period of political reform, growing dissent against the Tiburcio Carías Andino dictatorship, and worker agency and resistance against companies' control over workers and the North Coast banana regions dominated by U.S. companies. Actions and organizing among many unheralded banana finca workers consolidated the powerful general strike and brought about national outcomes in its aftermath, including the state's institution of the labor code and Ministry of Labor. -

Atlanta's Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class

“To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 by William Seth LaShier B.A. in History, May 2009, St. Mary’s College of Maryland A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Eric Arnesen James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that William Seth LaShier has passed the Final Examinations for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 20, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 William Seth LaShier Dissertation Research Committee Eric Arnesen, James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History, Dissertation Director Erin Chapman, Associate Professor of History and of Women’s Studies, Committee Member Gordon Mantler, Associate Professor of Writing and of History, Committee Member ii Acknowledgements I could not have completed this dissertation without the generous support of teachers, colleagues, archivists, friends, and most importantly family. I want to thank The George Washington University for funding that supported my studies, research, and writing. I gratefully benefited from external research funding from the Southern Labor Archives at Georgia State University and the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Books Library (MARBL) at Emory University. -

Strikebreaking and the Labor Market in the United States, 1881-1894

Strikebreaking and the Labor Market in the United States, 1881-1894 JOSHUA L. ROSENBLOOM Using data from a sample of over 2,000 individual strikes in the United States from 1881 to 1894 this article examines geographic, industrial, and temporal variations in the use of strikebreakers and the sources from which they were recruited. The use of strikebreakers was not correlated with the business cycle and did not vary appreciably by region or city size, but employers located outside the Northeast or in smaller cities were more likely to use replacement workers recruited from other places. The use of strikebreakers also varied considerably across industries, and was affected by union authorization and strike size. he forces determining wages and working conditions in American labor Tmarkets were radically altered in the decades after the Civil War. Im- provements in transportation and communication increased the ability of workers to migrate in response to differential opportunities and encouraged employers in labor-scarce areas to recruit workers from relatively more labor-abundant regions. As local labor markets became increasingly in- tegrated into broader regional and national labor markets during the late nineteenth century, competitive pressures on wages and working conditions grew, and the scope for local variations in the terms of employment de- clined.1 In many industries these pressures were further compounded by technological changes that encouraged the increasingly fine division of labor and enabled employers to replace skilled craftworkers with semiskilled operatives or unskilled laborers.2 The impact of these developments on American workers was profound. Broader labor markets and technological changes expanded employment opportunities for some workers, but for others they undermined efforts to increase wages and improve working conditions.3 The increasing elasticity The Journal of Economic History, Vol. -

Download (Pdf)

55th Congress. ) HOUSE OP BEPBESENTATIVES. (Doc.>\j » ANo.n K J. A207. 3d Session. Part 4. BULLETIN OF THE NO. 23— JULY, 1899. ISSUED EVERY OTHER MONTH. EDITED BY CARROLL D. WRIGHT, COMMISSIONER. OREN W. WEAVER, CHIEF CLERK. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 180 9. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis CONTENTS. Pago. The attitude of women’s clubs and associations toward social economics, by Ellen M. Henrotin............................................................................................ 501-545 The production of paper and pulp in the United States, from January 1 to J une 30, 1898.............................................................-......................................... 546-550 Digest of recent reports of State bureaus of labor statistics: Kansas ...• •.......................................................... 5o 1—553 Maine...................................... 553-555 Missouri................................................................................................................. 555, 556 Pennsylvania....................................................................................................... 557-559 West Virginia...................................................................................................... 559,560 Census of Massachusetts for 1895............................................................................ 561-567 Eleventh annual report -

Strikes in Canada, 1891-1950

CANADIAN STRIKES 123 Strikes in Canada, 1891-1950 II. Methods and Sources Douglas Cruikshank and Gregory S. Kealey NOW THAT THE STRIKES AND LOCKOUTS files of the Department of Labour have been microfilmed, they are likely to be consulted more than ever by labour historians and other researchers. If these records and the statis tics derived from them are to be used effectively, it is important to know how they were compiled. Soon after it was founded in 1900, the Department of Labour established a procedure for systematically gathering information on Canadian labour disputes, a procedure that was to remain essentially the same throughout the period covered in this report. When the department first received news of a strike, either from the correspondents of The Labour Gazette or through the regular press, it sent strike inquiry forms to representatives of the em ployers and employees involved in the dispute. Initially, a single form was mailed asking for the beginning and end dates of the dispute, the "cause or object" and "result," and the number of establishments and number of male and female workers directly and indirectly involved. In 1918 the depart ment began sending two forms — one to be returned immediately and the other after settlement — which requested more detailed information regard ing the usual working day and week. The department also asked for month ly reports from participants in longer strikes. These questionnaires sometimes provided all of the data needed to complete the various lists and statistical series, but because they were often not returned or contained conflicting responses, the department also relied on newspaper coverage and supplemen tary reports from fair wage and conciliation officers, Labour Gazette cor respondents, Royal Canadian Mounted Police informants, and Employment Service of Canada/Unemployment Insurance Commission officials. -

Direct Action

\ ASBEST if KILLS Most of us are aware, as of the different types of asbestos men. Furthermore, one would expect of the group chosen at late, a lot of publicity has only the blue type (crocidolite) been given to the material is dangerous. It is an opinion random 16 would die of lung asbestos. The controversial Y I myself have heard all to fre- cancer. Of the 632 insulation programme screened by Yorksh- quently and is a dangerous myth workers, 105 died of lung can- cer and 50 died of mesothelioma ire T.V., "Alice A Fight For however popular a notion it may The chances that anyone would Life", whiched slammed the be. In Britain alone, a trem- die of this disease are one or materials use in industry, as endous amount of research is two in ten thousand. done much to enlighten public taking place which suggests You may ask what is the gov- awareness to the health risks that one fibre, be it blue, wh- ernment doing about it? The associated with asbestos con- ite or brown, can kill. During answer to that is quite simply, taining materails. the l970's a voluntary ban was little or nothing. The fact Why so much controversy sh- put on Blue asbestos in this that at least 200 former empl- ould surround asbestos, is in country. However, it is inter- oyees of Acre Mill, Hebden itself cause for much discuss- esting to note that blue asbest- Bridge, a factory once owned ion, when one considers that os at the time amounted to only by Cape Asbestos, have contr- there is not one single use 5% of the industries business. -

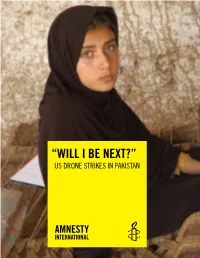

Drone Strikes in Pakistan

“WILL I BE NEXT?” US DRONE STRIKES IN PAKISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. Amnesty International Publications First published in 2013 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2013 Index: ASA 33/013/2013 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Nabeela, eight-year-old granddaughter of drone strike victim Mamana -

The 9/11 Commission Report

THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States official government edition For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 0-16-072304-3 CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

To Download the Whole Issue As a PDF

A LABOR NOTES GUIDE HOW TO STRIKE AND WIN 7435 Michigan Ave., Detroit, Michigan 48210 labornotes.org/strikes #488 November 2019 Jim West / jimwestphoto.com Jim West WHY STRIKES MATTER something that employers would prefer Strikes are where our power is. Without a credible we not notice: they need us. Workplaces are typically run as dic- tatorships. The discovery that your strike threat, workers are at the boss's mercy. boss does not have absolute power over you—and that in fact, you and your co- “Why do you rob banks?” a reporter Notes Conference that spring. “It is up workers can exert power over him—is a once asked Willie Sutton. “Because to us to give our labor, or to withhold it.” revelation. that’s where the money is,” the infa- That’s the fundamental truth on There’s no feeling like it. Going on mous thief replied. which the labor movement was built. strike changes you, personally and as a Why go on strike? Because that’s Strikes by unorganized workers led union. where our power is. to the founding of unions. Strikes won “Walking into work the first day back Teachers in West Virginia showed it in the first union contracts. Strikes over the chanting ‘one day longer, one day stron- 2018 when they walked out, in a strike years won bigger paychecks, vacations, ger’ was the best morning I’ve ever had at Verizon,” said Pam Galpern, a field that bubbled up from below, surprising seniority rights, and the right to tell the tech and mobilizer with Communica- even their statewide union leaders. -

ONA Nurses' Proposals

ONA/CMH 2016 Proposal Tracking Form Contract Proposal Summary Chart *Tentative Agreement subject to a ratification by ONA/CMH Nurses ONA Nurses' Proposals Contract Area ONA Nurses' Proposal Employer Response ONA Nurses' Rationale Tentative Agreement* Section Bargaining Team Hospital to pay ONA/CMH bargaining team for Don't agree. We haven't paid in the past. Salaried A good contract is important to both nurses and Withdrawn. Pay time spent in negotiations administrative staff are also putting in extra hours. CMH, but bargaining responsibly takes a significant time commitment. Besides working during their personal time, nurses also often lose pay or burn EL in order to participate. Administration won't A1, S2 bargain outside normal business hours. They get paid by CMH but they won't allow the same for the nurses' negotiating team. New Employee Increase ONA portion of NEO from 15 minutes to Don't agree. Schedule of NEO is too tight. We need 30 minutes to give a meaningful Withdrawn. A1, S3 Orientation (NEO) 30 minutes. presentation. New Positions Hospital to inform ONA/CMH of any new RN Don't agree. ONA doesn't need to know about ONA has the right to this information in order to Withdrawn. positions supervisory positions. determine whether positions belong in the bargaining unit. Providing it regularly would A1, S7 prevent potential grievances regarding proper placement in or out of the unit. Personnel Eliminate the word "regularly" from all definitions. Agree. Nurses are scheduled a range of hours. They are Eliminate the word "regularly" from all definitions. A4, S2 Categories not regularly or consistently scheduled any particular number. -

Strikes and Lockouts in Sweden Reconsidering Raphael's List Of

Strikes and Lockouts in Sweden Reconsidering Raphael’s List of Work Stoppages 1859-1902 Karlsson, Tobias 2019 Document Version: Other version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Karlsson, T. (2019). Strikes and Lockouts in Sweden: Reconsidering Raphael’s List of Work Stoppages 1859- 1902. (Lund Papers in Economic History. Education and the Labour Market; No. 2019:192). Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Lund Papers in Economic History No. 192, 2019 Education and the Labour Market Strikes and Lockouts in Sweden: Reconsidering Raphael’s List of Work Stoppages 1859-1902 Tobias Karlsson DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY, LUND UNIVERSITY Lund Papers in Economic History ISRN LUSADG-SAEH-P--19/192--SE+36 © The author(s), 2019 Orders of printed single back issues (no. -

Labor and Politics in the 1930'S

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Plan B Papers Student Theses & Publications 1-1-1967 Labor and Politics in the 1930's Charles E. Gillespie Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b Recommended Citation Gillespie, Charles E., "Labor and Politics in the 1930's" (1967). Plan B Papers. 618. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b/618 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Plan B Papers by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LABOR AND POLITICS IN THE 1930's (TITLE) BY Charles E. Gillespie PLAN B PAPER SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION AND PREPARED IN COURSE HISTORY 563 (Seminar on the 1930's) IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1967 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS PLAN B PAPER BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE DEGREE, M.S. IN ED. CL .J / lf I r,7 (c" 1 U r\ DAiE -- INTRODUCTION Today, American labor is recognized as a part of the greatest productive machine the world has ever known. The present status of labor, however, developed only within the past thirty years. In this general survey of labor in hte 1930's the many barriers and obstacles experienced in the growth of organized labor will be discussed. In the history of the United States periods of great change have emerged. New conditions and attitudes take root and break long established precedents.