AFGHANS in KARACHI: Migration, Settlement and Social Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Supervisory System of School Education in Sindh Province of Pakistan

A STUDY OF THE SUPERVISORY SYSTEM OF SCHOOL EDUCATION IN SINDH PROVINCE OF PAKISTAN By Mc) I-i a mm aci. I sma i 1 13x--cptil Thesis submitted to the University of London in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Administration. Department of Curriculum Studies Institute of Education University of London March 1991 USSR r- • GILGIT AGENCY • PAKISTAN I ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS q PESH4WAA ISLAMABAD OCCUPIED KASHMIR ( • MIRPUR (AK) RAWALPINDI \., .L.d.) 1■ •-....., CO f ) GUJRAT • --"'-',. • GUJRANWALA X' / 1).--1. •• .'t , C, p.'fj\.,./ ' • X • •• FAISALABAD LAHORE- NP* ... -6 , / / PUNJAB • ( SAHIWAL , / • ....-• .1 • QUETTA MULTAN I BALUCHISTAN RAHIMYAR KHAN/ • .1' \ •,' cc SINDH MIRPURKHAS %.....- \ • .■. • HYDERABAD •( ARABIAN SEA ABSTRACT The role of the educational supervisor is pivotal in ensuring the working of the system in accordance with general efficiency and national policies. Unfortunately Pakistan's system of educational management and supervision is too much entrenched in the legacy of past and has not succeeded, over the last forty years, in modifying and reforming itself in order to cope with the expanding and changing demands of eduCation in the country since independence( i.e. 1947). The empirical findings of this study support the following. Firstly, the existing style of supervision of secondary schools in Sindh, applied through traditional inspection of schools, is defective and outdated. Secondly, the behaviour of the educational supervisor tends to be too rigid and autocratic . Thirdly, the reasons for the resistance of existing system of supervision to change along the lines and policies formulated in recent years are to be found outside the education system and not merely within the education system or within the supervisory sub-system. -

Malir-Karachi

Malir-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Malir Karachi Gadap Town NA 408180381 GBLSS - HUSSAIN BLAOUCH Middle Boys 14,324 2,865 8,594 5,729 2,865 11,459 45,836 11,459 57,295 2 Malir Karachi Gadap Town NA 408180436 GBELS - HAJI IBRAHIM BALOUCH Elementary Mixed 24,559 4,912 19,647 4,912 4,912 19,647 78,588 19,647 98,236 3 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180426 GBELS - HASHIM KHASKHELI Elementary Boys 42,250 8,450 33,800 8,450 8,450 33,800 135,202 33,800 169,002 4 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180434 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.3 OLD Elementary Mixed 35,865 7,173 28,692 7,173 7,173 28,692 114,769 28,692 143,461 5 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180435 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.3 NEW Elementary Mixed 24,882 4,976 19,906 4,976 4,976 19,906 79,622 19,906 99,528 6 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 2-Darsano Channo 408180073 GBELS - AL-HAJ DUR MUHAMMAD BALOCH Elementary Boys 36,374 7,275 21,824 14,550 7,275 29,099 116,397 29,099 145,496 7 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 2-Darsano Channo 408180428 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.1 Elementary Mixed 33,116 6,623 26,493 6,623 6,623 26,493 105,971 26,493 132,464 8 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 3-Gujhro 408180441 GBELS - SIRAHMED VILLAGE Elementary Mixed 38,725 7,745 30,980 7,745 7,745 30,980 123,919 -

12086393 01.Pdf

Exchange Rate 1 Pakistan Rupee (Rs.) = 0.871 Japanese Yen (Yen) 1 Yen = 1.148 Rs. 1 US dollar (US$) = 77.82 Yen 1 US$ = 89.34 Rs. Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Karachi Transportation Improvement Project ................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Background................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1.2 Work Items ................................................................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.3 Work Schedule ........................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.2 Progress of the Household Interview Survey (HIS) .......................................................................... 1-5 1.3 Seminar & Workshop ........................................................................................................................ 1-5 1.4 Supplementary Survey ....................................................................................................................... 1-6 1.4.1 Topographic and Utility Survey................................................................................................. 1-6 1.4.2 Water Quality Survey ............................................................................................................... -

Subject: Details of Vehicles and Routes Plying for MAJU As Third Party

March 17, 2021 Muhammad Ali Jinnah University, Block – 6, PECHS, Shahrah-E- Faisal, Karachi. Subject: Details of Vehicles and Routes Plying for MAJU as Third Party Rout Driver Cell Registration Total Capacity Driver Name Vehicle Type Rout Code No. No. Capacity Utilized MAJU 1 Kumail Hussain 03162458082 CU-9807 Hijet 7 7 Model Colony - Tariq Bin Ziyad – Malir Halt MAJU 2 Kashif Hussain 03142994018 CD-5224 Hiroof Bolan 7 7 Khokrapar - Malir Cantt. – Shahrah-E-Faisal MAJU 3 Raheel Ahmed 03096551061 CR-9530 Hiroof Bolan 7 7 Malir City – Shah Faisal – Drig Road MAJU 4 Raja Khan 03142254080 CV-2294 Suzuki Every 7 6 Landhi 1 & 6 - Korangi 1 & 2 ½ - Crossing MAJU 5 Faisal Khan 03162111826 CN-9870 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Korangi 5 & 5 1/2 – Qayyumabad – Kala Pul MAJU 6 Yahya 03101043920 CG-7681 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Saadi Town - Mosmiat - New Rizviya – Johar 1 MAJU 7 M. Ibrahim 03011109270 JF-7063 Hilex 15 14 Safora - Samama - Continental – Gul. Johar MAJU 8 Imran 03340298838 CU-6365 Hiroof Bolan 7 5 Maymaar - Scheme 33 - Abul Asfahani Road MAJU 9 Sunny 03322399422 CS-6522 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Abul Afahani - Nipa - Hasan Square – Stadium MAJU 10 M. Shariq 03222112478 CG-7001 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Sarjani - North Karachi - North Nazimabad MAJU 11 M. Zakir 03118481919 CP-9062 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 New Nazimabad - Anda Mod - North Nazimabd MAJU 12 Fahim 03337143644 CP-8171 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Nagan - Bafarzone - Sohrab Goth – Rashid Min. MAJU 13 Nasir 03008967707 CN-2540 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Bada Board - Nazimabad – Paposh – Lasbila MAJU 14 Shehroz 03172175553 CK-8868 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Board office - Golimar - Lalo Kheth – New town MAJU 15 Moiz 03113246303 CY-2289 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Five Star - Sakhi Hasan – FB Area – Azizabad MAJU 16 Ali 03342575308 CN-4047 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Gulberg - Waterpump - Mukka Chok – 13D MAJU 17 Aashiq 03022480771 CU-0496 Hiroof Bolan 7 7 FB Area - Ancholi - Alnoor - Sohrab Goth MAJU 18 M. -

Pakistan's Future Policy Towards Afghanistan. a Look At

DIIS REPORT 2011:08 DIIS REPORT PAKISTAN’S FUTURE POLICY TOWARDS AFGHANISTAN A LOOK AT STRATEGIC DEPTH, MILITANT MOVEMENTS AND THE ROLE OF INDIA AND THE US Qandeel Siddique DIIS REPORT 2011:08 DIIS REPORT DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2011:08 © Copenhagen 2011, Qandeel Siddique and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: The Khyber Pass linking Pakistan and Afghanistan. © Luca Tettoni/Robert Harding World Imagery/Corbis Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-455-7 Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk This publication is part of DIIS’s Defence and Security Studies project which is funded by a grant from the Danish Ministry of Defence. Qandeel Siddique, MSc, Research Assistant, DIIS [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2011:08 Contents Abstract 6 1. Introduction 7 2. Pakistan–Afghanistan relations 12 3. Strategic depth and the ISI 18 4. Shift of jihad theatre from Kashmir to Afghanistan 22 5. The role of India 41 6. The role of the United States 52 7. Conclusion 58 Defence and Security Studies at DIIS 70 3 DIIS REPORT 2011:08 Acronyms AJK Azad Jammu and Kashmir ANP Awani National Party FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FDI Foreign Direct Investment FI Fidayeen Islam GHQ General Headquarters GoP Government -

Analysis of Pakistan's Policy Towards Afghan Refugees

• p- ISSN: 2521-2982 • e-ISSN: 2707-4587 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2019(IV-III).04 • ISSN-L: 2521-2982 DOI: 10.31703/gpr.2019(IV-III).04 Muhammad Zubair* Muhammad Aqeel Khan† Muzamil Shah‡ Analysis of Pakistan’s Policy Towards Afghan Refugees: A Legal Perspective This article explores Pakistan’s policy towards Afghan refugees • Vol. IV, No. III (Summer 2019) Abstract since their arrival into Pakistan in 1979. As Pakistan has no • Pages: 28 – 38 refugee related law at national level nor is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its Protocol of 1967; but despite of all these obstacles it has welcomed the refugees from Afghanistan after the Russian aggression. During their Headings stay here in Pakistan, these refugees have faced various problems due to the non- • Introduction existence of the relevant laws and have been treated under the Foreigner’s Act • Pakistan's Policy Towards Refugees of 1946, which did not apply to them. What impact this absence of law has made and Immigrants on the lives of these Afghan refugees? Here various phases of their arrival into • Overview of Afghan Refugees' Pakistan as well as the shift in policies of the government of Pakistan have been Situation in Pakistan also discussed in brief. This article explores all these obstacles along with possible • Conclusion legal remedies. • References Key Words: Influx, Refugees, Registration, SAFRON and UNHCR. Introduction Refugees are generally casualties of human rights violations. What's more, as a general rule, the massive portion of the present refugees are probably going to endure a two-fold violation: the underlying infringement in their state of inception, which will more often than not underlie their flight to another state; and the dissent of a full assurance of their crucial rights and opportunities in the accepting state. -

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan

February 2002 Vol. 14, No. 2(G) AFGHANISTAN, IRAN, AND PAKISTAN CLOSED DOOR POLICY: Afghan Refugees in Pakistan and Iran “The bombing was so strong and we were so afraid to leave our homes. We were just like little birds in a cage, with all this noise and destruction going on all around us.” Testimony to Human Rights Watch I. MAP OF REFUGEE A ND IDP CAMPS DISCUSSED IN THE REPORT .................................................................................... 3 II. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 III. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 6 To the Government of Iran:....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 To the Government of Pakistan:............................................................................................................................................................... 7 To UNHCR :............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Health, Education and Literacy Programme Annual Report

Health, Education and Literacy Programme Annual Report 2016-2017 Contents Mission Executive Committee Management General Body Members Sub committees Chairperson’s Message About HELP Our Donors Accountability and Transparency Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Our Projects Our Friends Financials / Audit Report Our Mission “Through needs assessment to design and implement replicable models of health promotion, health delivery and education for women and children” Executive Committee (Honorary) Prof. Dure Samin Akram Chairperson Associate Prof. S.K Kausar Vice President Prof. Dr. Fehmina Arif General Secretary Dr. Gulrukh Nency Joint Secretary Associate Prof. Dr. Neel Kanth Treasurer Members Ms. Mona Sheikh. Mr. Fareed Khan Ms. Hilda Saeed Ms. Rabia Agha Ms. Reema Jaffery Management Senior Program Manager Dr. Yasmeen Suleman Program Manager Dr. Amara Shakeel General Body members Dr. Fazila Zamindar Dr. Jaleel Siddiqui Dr. Sabin Adil Dr. Qadir Pathan Dr. Shakir Mustafa Ms. Shala Usmani Ms. Erum Ghazi Dr. Imtiaz Mandan Annual Report 2017 Sub committees Audit Committee Mr. Farid Khan Prof. Dr. Fehmina Arif Dr. Yasmeen Suleman Fund Raising Committee Ms. Reema Jaffery Dr. Fazila Zamindar Dr. Amara Shakeel Ms. Mona Shaikh Ms. Rabia Agha Research Committee Prof. Dure Samin Akram Associate Prof. Dr. Neel Kanth Associate Prof. S.K Kausar Prof. Dr. Fehmina Arif Purchasing and Procurement committee Prof. Fehmina Arif Dr. Yasmeen Suleman Associate Prof. Neel Kanth Editorial Board Dr. Yasmeen Suleman Ms. Hilda Saeed Annual Report 2017 Chairperson’s Message HELP has been blessed with many friends, well-wishers and philanthropic assistance. In return, we continue to push towards our Mission “to help those who help themselves”. This translates to empowering people in communities towards improving their living environment and standards of living. -

Health Bulletin July.Pdf

July, 2014 - Volume: 2, Issue: 7 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: Polio spread feared over mass displacement 02 English News 2-7 Dengue: Mosquito larva still exists in Pindi 02 Lack of coordination hampering vaccination of NWA children 02 Polio Cases Recorded 8 Delayed security nods affect polio drives in city 02 Combating dengue: Fumigation carried out in rural areas 03 Health Profile: 9-11 U.A.E. polio campaign vaccinates 2.5 million children in 21 areas in Pakistan 03 District Multan Children suffer as Pakistan battles measles epidemic 03 Health dept starts registering IDPs to halt polio spread 04 CDA readies for dengue fever season 05 Maps 12,14,16 Ulema declare polio immunization Islamic 05 Polio virus detected in Quetta linked to Sukkur 05 Articles 13,15 Deaths from vaccine: Health minister suspends 17 officials for negligence 05 Polio vaccinators return to Bara, Pakistan, after five years 06 Urdu News 17-21 Sewage samples polio positive 06 Six children die at a private hospital 06 06 Health Directory 22-35 Another health scare: Two children infected with Rubella virus in Jalozai Camp Norwegian funding for polio eradication increased 07 MULTAN HEALTH FACILITIES ADULT HEALTH AND CARE - PUNJAB MAPS PATIENTS TREATED IN MULTAN DIVISION MULTAN HEALTH FACILITIES 71°26'40"E 71°27'30"E 71°28'20"E 71°29'10"E 71°30'0"E 71°30'50"E BUZDAR CLINIC TAYYABA BISMILLAH JILANI Rd CLINIC AMNA FAMILY il BLOOD CLINIC HOSPITAL Ja d M BANK R FATEH MEDICAL MEDICAL NISHTER DENTAL Legend l D DENTAL & ORAL SURGEON a & DENTAL STORE MEDICAL COLLEGE A RABBANI n COMMUNITY AND HOSPITAL a CLINIC R HOSPITALT C HEALTH GULZAR HOSPITAL u "' Basic Health Unit d g CENTER NAFEES MEDICARE AL MINHAJ FAMILY MULTAN BURN UNIT PSYCHIATRIC h UL QURAN la MATERNITY HOME CLINIC ZAFAR q op Blood Bank N BLOOD BANK r ishta NIAZ CLINIC R i r a Rd X-RAY SIYAL CLINIC d d d SHAHAB k a Saddiqia n R LABORATORY FAROOQ k ÷Ó o Children Hospital d DECENT NISHTAR a . -

(Rfp) for Front End Collection and Disposal of Municipal Solid Waste for Zone Korangi (Dmc Korangi Area) Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) FOR FRONT END COLLECTION AND DISPOSAL OF MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE FOR ZONE KORANGI (DMC KORANGI AREA) KARACHI, SINDH, PAKISTAN. Executive Director (Operation-I) Sindh Solid Waste Management Board (SSWMB) Govt. of Sindh SSWMB – NIT-16 Table of Content Sindh Solid Waste Management Board Section-I Preamble Clause# Page# 1.1 Purpose of Request for Proposal 8 1.2 Scope of Work/Assignment 8 1.3 Brief Description of DMC Korangi 8 1.4 MAP of DMC Korangi 9 1.5 Definition & Interpretation 9 1.6 Abbreviation 10 1.7 Section of RFP/Bidding Documents 11 1.8 Procuring Agency Right to cancel any or all proposals/tenders 11 Section-II Instructions to Contractors/Bidders. Clause# Page# 2.1 Information related to procuring agency 13 2.2 Language of proposal and correspondence 13 2.3 Method of Procurement 13 2.4 Period of Contract 13 2.5 Pre-proposal Meeting 13 2.6 Clarification and modifications of Bidding Document 14 2.7 Visit of the area of Service 14 2.8 Utilization of Existing Work Force on SWM of DMC Korangi 14 2.9 Utilization of Existing Solid Waste Collection & Transportation Vehicle of 16 DMC Korangi. 2.10 Utilization of Existing Facilities i.e. Workshop, Offices of DMC Korangi 17 2.11 Amendment through Addendums 17 2.12 Cancelation of Tender before Tender Time 17 2.13 Proposal Preparation Cost/Cost of bidding 17 2.14 Bid submitted by a Joint Venture/Consortium 18 2.15 Place, date, time and manner of submission of Tender/Bid Document 19 2.16 Currency Unit of Offers and Payments 21 2.17 Conditional and Partial Offers 22 2.18 -

Shuttle Route

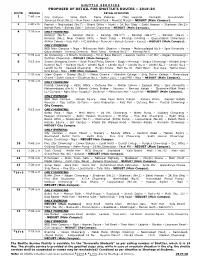

SHUTTLE SERVICES PROPOSED OF DETAIL FOR SHUTTLE’S ROUTES – 2019-20 ROUTE TIMINGS DETAIL OF ROUTES 1 7:40 a.m City Campus – Jama Cloth – Radio Pakistan – 7Day Hospital – Numaish – Gurumandir – Jamshed Road (No.3) – New Town – Askari Park – Mumtaz Manzil – NEDUET (Main Campus). 2 7:40 a.m Paposh – Nazimabad (No.7) – Board Office – Hydri – 2K Bus Stop – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman (No.2)– Namak Bank – Sohrab Goth – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 4 7:20 a.m ONLY MORNING: Korangi (No.5) – Korangi (No.4) – Korangi (No.31/2) – Korangi (No.21/2) – Korangi (No.2) – Korangi (No.1, Near Chakra Goth) – Nasir Jump – Korangi Crossing – Qayyumabad Chowrangi – Akhtar Colony – Kala Pull – FTC Building – Nursery – Baloch Colony – Karsaz – NEDUET (Main Campus). ONLY EVENING: NED Main Campus – Nipa – Millennium Mall– Stadium – Karsaz – Mehmoodabad No.6 – Iqra University – Qayyumabad – Korangi Crossing – Nasir Jump – Korangi No.21/2 – Korangi No.5. 5 7:45 a.m 4K Chowrangi – 2 Minute Chowrangi – 5C-4 (Bara Market) – Saleem Centre – U.P Mor – Nagan Chowrangi – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 6 7:15 a.m Shama Shopping Centre – Shah Faisal Police Station – Bagh-e-Korangi – Singer Chowrangi – Khaddi Stop – Korangi No.5 – Korangi No.6 – Landhi No.6 – Landhi No.5 – Landhi No.4 – Landhi No.3 – Landhi No.1 – Landhi No.89 – Dawood Chowrangi – Murghi Khana – Malir No.15 – Malir Hault – Star Gate – Natha Khan – Drig Road – Nipa – NED Main Campus. 7 7:35 a.m Islam Chowk – Orangi (No.5) – Metro Cinema – Abdullah College – Ship Owner College – Qalandarya Chowk – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman No.1 – Buffer Zone – Fazal Mill – Nipa – NEDUET (Main Campus). -

List of Settlements Evicted 1997

List of displaced settlements 1997 – 2005 Urban Resource Centre A-2/2, 2nd Floor, Westland Trade Centre, Commercial Area, Shaheed-e-Millat Road, Karachi Co-operative Housing Society Union, Block 7 & 8 Karachi Pakistan Tel: +92 21 - 4559317 Fax: 4387692 Web site : www.urckarachi.org E-mail: [email protected] XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX I Appendix – : List 1 Details of the some recent Evictions cases Settlement /area Date No. Reasons Houses bulldozed Noor Muhammad Village Karsaz 29/05/97 400 KWSB wanted to build its office building Junejo Town Manzoor Colony 05/10/97 150 KDA land Garam Chashma Goth Manghopir 22/11/97 150 Land grabbers were involved. Umer Farooq Town Kalapul 23/02/98 100 Bridge extension Manzoor Colony 21/05/98 20 Liaquat Colony Lyari 17/10/98 190 KMC declared a 100 years old settlement as an amenity plot. Glass Tower Clifton 26/11/98 10 Parking for Glass Tower Ghareebabad, Sabzi Mandi and Quaid 28/12/98 250 Access road for law & order e Azam Colony agencies Buffer Zone 10/02/99 35 Land dispute Kausar Niazi colony North Nazimabad 17/02/99 30 Land dispute Zakri Baloch Goth Gulistan-e-Jauhar 15/03/99 250 Builders wanted the land for high rise construction Al Hilal Society Sabzi Mandi 15/03/99 62 Builders involved Sikanderabad Clony KPT 23/08/99 40 KPT reclaimed its land Gudera Camp New Karachi 17/11/99 350 Operation against encroachments Sher Pao Colony M.A. Society 29/11/99 60 Amenity plot Gilani railway station 20/01/00 160 Railway land Grumandir 02/08/00 37 shops Road extension by the KMC Chakara Goth Nasir Colony