The Improvisation of Tubby Hayes in ‘The New York Sessions’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annie Ross Uk £3.25

ISSUE 162 SUMMER 2020 ANNIE ROSS UK £3.25 Photo by Merlin Daleman CONTENTS Photo by Merlin Daleman ANNIE ROSS (1930-2020) The great British-born jazz singer remembered by VAL WISEMAN and DIGBY FAIRWEATHER (pages 12-13) THE 36TH BIRMINGHAM, SANDWELL 4 NEWS & WESTSIDE JAZZ FESTIVAL Birmingham Festival/TJCUK OCTOBER 16TH TO 25TH 2020 7 WHAT I DID IN LOCKDOWN [POSTPONED FROM ORIGINAL JULY DATES] Musicians, promoters, writers 14 ED AND ELVIN JAZZ · BLUES · BEBOP · SWING Bicknell remembers Jones AND MORE 16 SETTING THE STANDARD CALLUM AU on his recent album LIVE AND ROCKING 18 60-PLUS YEARS OF JAZZ MORE THAN 90% FREE ADMISSION BRIAN DEE looks back 20 THE V-DISC STORY Told by SCOTT YANOW 22 THE LAST WHOOPEE! Celebrating the last of the comedy jazz bands 24 IT’S TRAD, GRANDAD! ANDREW LIDDLE on the Bible of Trad FIND US ON FACEBOOK 26 I GET A KICK... The Jazz Rag now has its own Facebook page. with PAOLO FORNARA of the Jim Dandies For news of upcoming festivals, gigs and releases, features from the archives, competitions and who 26 REVIEWS knows what else, be sure to ‘like’ us. To find the Live/digital/ CDs page, simply enter ‘The Jazz Rag’ in the search bar at the top when logged into Facebook. For more information and to join our mailing list, visit: THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 BRITISH JAZZ AWARDS CANCELLED WWW.BIRMINGHAMJAZZFESTIVAL.COM Fax: 0121 454 9996 Email: [email protected] This is the time of year when Jazz Rag readers expect to have the opportunity to vote for the Jazz Oscars, the British Jazz Awards. -

Bbc Music Jazz 4

Available on your digital radio, online and bbc.co.uk/musicjazz THURSDAY 10th NOVEMBER FRIDAY 11th NOVEMBER SATURDAY 12th NOVEMBER SUNDAY 13th NOVEMBER MONDAY 14th NOVEMBER JAZZ NOW LIVE WITH JAZZ AT THE MOVIES WITH 00.00 - SOMERSET BLUES: 00.00 - JAZZ AT THE MOVIES 00.00 - 00.00 - WITH JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 1) SOWETO KINCH CONTINUED JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 2) THE STORY OF ACKER BILK Clarke Peters tells the strory of Acker Bilk, Jamie Cullum explores jazz in films – from Al Soweto Kinch presents Jazz Now Live from Jamie celebrates the work of some of his one of Britain’s finest jazz clarinettists. Jolson to Jean-Luc Godard. Pizza Express Dean Street in London. favourite directors. NEIL ‘N’ DUD – THE OTHER SIDE JAZZ JUNCTIONS: JAZZ JUNCTIONS: 01.00 - 01.00 - ELLA AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL 01.00 - 01.00 - OF DUDLEY MOORE JAZZ ON THE RECORD THE BIRTH OF THE SOLO Neil Cowley's tribute to his hero Dudley Ella Fitzgerald, live at the Royal Albert Hall in Guy Barker explores the turning points and Guy Barker looks at the birth of the jazz solo Moore, with material from Jazz FM's 1990 heralding the start of Jazz FM. pivotal events that have shaped jazz. and the legacy of Louis Armstrong. archive. GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER’S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - 02.00 - GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - THE OTHER SIDE OF THE POND: 02.00 - TRUMPET MASTERS (PT. 2) JAZZ FESTIVALS (PT. 1) JAZZ ON FILM (PT. -

This Is Our Music V.2-2

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by BCU Open Access 20/11/2015 16:38:00 This Is Our Music?: Tradition, community and musical identity in contemporary British jazz Mike Fletcher As we reach the middle of the second decade of the twenty-first century we are also drawing close to the centenary of jazz as a distinct genre of music. Of course, attempting to pinpoint an exact date would be a futile endeavour but nevertheless, what is clear is that jazz has evolved at a remarkable rate during its relatively short lifespan. This evolution, which encompassed many stylistic changes and innovations, was aided in no small part by the rapid technological advances of the twentieth century. Thus, what was initially a relatively localised music has been transformed into a truly global art form. Within a few short decades of the birth of the music, records, radio broadcasts and globe-trotting American jazz performers had already spread the music to a listening audience worldwide, and it was not long after this that musicians began to make attempts to ‘adapt jazz to the social circumstances and musical standards with which they were more familiar’.1 In the intervening decades, subsequent generations of indigenous musicians have formed national lineages that run parallel to those in America, and variations in cultural and social conditions have resulted in a diverse range of performance practices, all of which today fall under the broad heading of jazz. As a result, contemporary musicians and scholars alike are faced with increasing considerations of ownership and authenticity, ultimately being compelled to question whether the term jazz is still applicable to forms of music making that have grown so far away from their historical and geographic origins. -

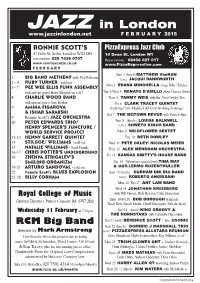

JAZZ in London F E B R U a R Y 2015

JAZZ in London www.jazzinlondon.net F E B R U A R Y 2015 RONNIE SCOTT’S PizzaExpress Jazz Club 47 Frith St. Soho, London W1D 4HT 10 Dean St. London W1 reservations: 020 7439 0747 Reservations: 08456 027 017 www.ronniescotts.co.uk www.PizzaExpresslive.com F E B R U A R Y Sun 1 (lunch) MATTHEW VanKAN with Phil Robson 1 BIG BAND METHENY (eve) JACQUI DANKWORTH 2 - 4 RUBY TURNER - sold out Mon 2 sings Billie Holiday 5 - 7 PEE WEE ELLIS FUNK ASSEMBLY EDANA MINGHELLA with special guest Huey Morgan on 6 & 7 Tue 3/Wed 4 RENATO D’AIELLO plays Horace Silver 8 CHARLIE WOOD BAND Thur 5 TAMMY WEIS with the Tom Cawley Trio with special guest Guy Barker Fri 6 CLARK TRACEY QUINTET 9 AMINA FIGAROVA featuring Chris Maddock & Henry Armburg-Jennings & ISHAR SARABSKI Sat 7 THE MOTOWN REVUE with Patrick Alan 9 Ronnie Scott’s JAZZ ORCHESTRA 10 PETER EDWARDS TRIO/ Sun 8 (lunch) LOUISE BALKWILL (eve) HENRY SPENCER’S JUNCTURE / SOWETO KINCH BAND WORLD SERVICE PROJECT Mon 9 WILDFLOWER SEXTET 11- 13 KENNY GARRETT QUINTET Tue 10 BETH ROWLEY 14 STILGOE/ WILLIAMS - sold out Wed 11 PETE OXLEY/ NICOLAS MEIER 15 - Soul Family NATALIE WILLIAMS Thur 12 ALEX MENDHAM ORCHESTRA 16-17 CHRIS POTTER’S UNDERGROUND Fri 13 18 ZHENYA STRIGALEV’S KANSAS SMITTY’S HOUSE BAND SMILING ORGANIZM Sat 14 Valentine’s special with TINA MAY 19-21 ARTURO SANDOVAL - sold out & GUILLERMO ROZENTHULLER 22 Ronnie Scott’s BLUES EXPLOSION Sun 15 (lunch) DURHAM UNI BIG BAND 23-28 BILLY COBHAM (eve) ROBERTO ANGRISANI Mon 16/ Tue17 ANT LAW BAND Wed 18 JONATHAN KREISBERG Royal College of Music with Will Vinson, Rick Rosato, Colin Stranahan (Britten Theatre) Prince Consort Rd. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

Music Outside? the Making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde 1968-1973

Banks, M. and Toynbee, J. (2014) Race, consecration and the music outside? The making of the British jazz avant-garde 1968-1973. In: Toynbee, J., Tackley, C. and Doffman, M. (eds.) Black British Jazz. Ashgate: Farnham, pp. 91-110. ISBN 9781472417565 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/222646/ Deposited on 28 August 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Race, Consecration and the ‘Music Outside’? The making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde: 1968-1973 Introduction: Making British Jazz ... and Race In 1968 the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), the quasi-governmental agency responsible for providing public support for the arts, formed its first ‘Jazz Sub-Committee’. Its main business was to allocate bursaries usually consisting of no more than a few hundred pounds to jazz composers and musicians. The principal stipulation was that awards be used to develop creative activity that might not otherwise attract commercial support. Bassist, composer and bandleader Graham Collier was the first recipient – he received £500 to support his work on what became the Workpoints composition. In the early years of the scheme, further beneficiaries included Ian Carr, Mike Gibbs, Tony Oxley, Keith Tippett, Mike Taylor, Evan Parker and Mike Westbrook – all prominent members of what was seen as a new, emergent and distinctively British avant-garde jazz scene. Our point of departure in this chapter is that what might otherwise be regarded as a bureaucratic footnote in the annals of the ACGB was actually a crucial moment in the history of British jazz. -

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic “When Johnny Cash comes on the radio, no one changes the station. It’s a voice, a name with a soul that cuts across all boundaries and it’s a voice we all believe. Yours is a voice that speaks for the saints and the sinners – it’s like branch water for the soul. Long may you sing out. Loud.” – Tom Waits audio int‘l p. o. box 560 229 60407 frankfurt/m. germany www.audio-intl.com Catalog: IMP 6008 Format: 180-gram LP tel: 49-69-503570 mobile: 49-170-8565465 Available Spring 2011 fax: 49-69-504733 To order/preorder, please contact your favorite audiophile dealer. Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat. Shout-Cisco (three 200g 45rpm LPs). Joan Baez, In Concert. Vanguard-Cisco (180g LP). The 20th Anniversary reissue of Warnes’ stunning Now-iconic performances, recorded live at college renditions from the songbook of Leonard Cohen. concerts throughout 1961-62. The Cisco 45 rpm LPs define the state of the art in vinyl playback. Holly Cole, Temptation. Classic Records (LP). The distinctive Canadian songstress and her loyal Jennifer Warnes, The Hunter. combo in smoky, jazz-fired takes on the songs of Private-Cisco (200g LP). Tom Waits. Warnes’ post-Famous Blue Raincoat release that also showcases her own vivid songwriting talents in an Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Déjá Vu. exquisite performance and recording. Atlantic-Classic (200g LP). A classic: Great songs, great performances, Doc Watson, Home Again. Vanguard-Cisco great sound. The best country guitar-picker of his day plays folk ballads, bluegrass, and gospel classics. -

The First Modern Piano Quartet a Gallery of Gershwin Mp3, Flac, Wma

The First Modern Piano Quartet A Gallery Of Gershwin mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: A Gallery Of Gershwin Country: US Released: 1958 Style: Space-Age, Easy Listening MP3 version RAR size: 1385 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1871 mb WMA version RAR size: 1522 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 850 Other Formats: WMA MP1 MP2 FLAC WAV DTS AIFF Tracklist A1 Fascinatin' Rhythm 3:08 A2 Love Walked In 3:03 A3 Clap Yo' Hands 2:05 A4 The Man I Love 3:06 A5 Someone To Watch Over Me 3:11 A6 Mine 2:36 B1 Liza 2:14 B2 Bess You Is My Woman 4:45 B3 Our Love Is Here To Stay 3:25 B4 Somebody Loves Me 3:35 B5 Soon 3:05 Credits Piano – Dick Marx, Eddie Costa, Hank Jones, John Costa Notes Laminated gatefold cover with mono catalog number on spine and Black and Silver "stereo" sticker on front. Stereo banner and catalog number on deep groove maroon labels with silver/gold print, "Manufactured by Decca Records, Inc. New York USA." Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side 1): 7 6206 1 Matrix / Runout (Side 2): 7 6207 5 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Manny Albam And His Manny Albam And His Orchestra Introducing The Orchestra Introducing CRL 59102 First Modern Piano Quartet - Coral CRL 59102 US 1958 The First Modern A Gallery Of Gershwin (LP, Piano Quartet Album, Mono, Gat) Manny Albam And His Manny Albam And His Orchestra Introducing The Orchestra Introducing CRL 59102 First Modern Piano Quartet - Coral CRL 59102 US 1958 The First Modern A Gallery Of Gershwin (LP, Piano Quartet Album, Mono, Promo, Gat) The First Modern The First Modern Piano CRL Piano Quartet, Manny Quartet, Manny Albam And CRL Coral US 1958 759102 Albam And His His Orchestra - A Gallery Of 759102 Orchestra Gershwin (LP, Album, Gat) Related Music albums to A Gallery Of Gershwin by The First Modern Piano Quartet Various - I Got Rhythm (Jazz Stars Play Gershwin) Dvořák, London Symphony Orchestra, Istvan Kertesz - Symphonic Variations / The Golden Spinning- Wheel Mozart, The Concertgebouw Orchestra Of Amsterdam, Eduard Van Beinum - Symphony No. -

Boosey & Hawkes

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Howell, Jocelyn (2016). Boosey & Hawkes: The rise and fall of a wind instrument manufacturing empire. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16081/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Boosey & Hawkes: The Rise and Fall of a Wind Instrument Manufacturing Empire Jocelyn Howell PhD in Music City University London, Department of Music July 2016 Volume 1 of 2 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Figures...................................................................................................................................... -

JREV3.8FULL.Pdf

JAZZ WRITING? I am one of Mr. Turley's "few people" who follow The New Yorker and are jazz lovers, and I find in Whitney Bal- liett's writing some of the sharpest and best jazz criticism in the field. He has not been duped with "funk" in its pseudo-gospel hard-boppish world, or- with the banal playing and writing of some of the "cool school" Californians. He does believe, and rightly so, that a fine jazz performance erases the bound• aries of jazz "movements" or fads. He seems to be able to spot insincerity in any phalanx of jazz musicians. And he has yet to be blinded by the name of a "great"; his recent column on Bil- lie Holiday is the most clear-headed analysis I have seen, free of the fan- magazine hero-worship which seems to have been the order of the day in the trade. It is true that a great singer has passed away, but it does the late Miss Holiday's reputation no good not to ad• LETTERS mit that some of her later efforts were (dare I say it?) not up to her earlier work in quality. But I digress. In Mr. Balliett's case, his ability as a critic is added to his admitted "skill with words" (Turley). He is making a sincere effort to write rather than play jazz; to improvise with words,, rather than notes. A jazz fan, in order to "dig" a given solo, unwittingly knows a little about the equipment: the tune being improvised to, the chord struc• ture, the mechanics of the instrument, etc. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

Skidmore Lead Miners of Derbyshire, and Their Descendants 1600-1915

Skidmore Lead Miners of Derbyshire & their descendants 1600-1915 Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study 2015 www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com [email protected] SKIDMORE LEAD MINERS OF DERBYSHIRE, AND THEIR DESCENDANTS 1600-1915 by Linda Moffatt 2nd edition by Linda Moffatt© March 2016 1st edition by Linda Moffatt© 2015 This is a work in progress. The author is pleased to be informed of errors and omissions, alternative interpretations of the early families, additional information for consideration for future updates. She can be contacted at [email protected] DATES Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate.