Learning.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nominalism and Constructivism in Seventeenth-Century Mathematical Philosophy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Historia Mathematica 32 (2005) 33–59 www.elsevier.com/locate/hm Nominalism and constructivism in seventeenth-century mathematical philosophy David Sepkoski Department of History, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH 44074, USA Available online 27 November 2003 Abstract This paper argues that the philosophical tradition of nominalism, as evident in the works of Pierre Gassendi, Thomas Hobbes, Isaac Barrow, and Isaac Newton, played an important role in the history of mathematics during the 17th century. I will argue that nominalist philosophy of mathematics offers new clarification of the development of a “constructivist” tradition in mathematical philosophy. This nominalist and constructivist tradition offered a way for contemporary mathematicians to discuss mathematical objects and magnitudes that did not assume these entities were real in a Platonic sense, and helped lay the groundwork for formalist and instrumentalist approaches in modern mathematics. 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Résumé Cet article soutient que la tradition philosophique du nominalisme, évidente dans les travaux de Pierre Gassendi, Thomas Hobbes, Isaac Barrow et Isaac Newton, a joué un rôle important dans l’histoire des mathématiques pendant le dix-septième siècle. L’argument princicipal est que la philosophie nominaliste des mathématiques est à la base du développement d’une tradition « constructiviste » en philosophie mathématique. Cette tradition nominaliste et constructiviste a permis aux mathématiciens contemporains de pouvoir discuter d’objets et quantités mathématiques sans présupposer leur réalité au sens Platonique du terme, et a contribué au developpement desétudes formalistes et instrumentalistes des mathématiques modernes. -

Calculation and Controversy

calculation and controversy The young Newton owed his greatest intellectual debt to the French mathematician and natural philosopher, René Descartes. He was influ- enced by both English and Continental commentators on Descartes’ work. Problems derived from the writings of the Oxford mathematician, John Wallis, also featured strongly in Newton’s development as a mathe- matician capable of handling infinite series and the complexities of calcula- tions involving curved lines. The ‘Waste Book’ that Newton used for much of his mathematical working in the 1660s demonstrates how quickly his talents surpassed those of most of his contemporaries. Nevertheless, the evolution of Newton’s thought was only possible through consideration of what his immediate predecessors had already achieved. Once Newton had become a public figure, however, he became increasingly concerned to ensure proper recognition for his own ideas. In the quarrels that resulted with mathematicians like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) or Johann Bernoulli (1667–1748), Newton supervised his disciples in the reconstruction of the historical record of his discoveries. One of those followers was William Jones, tutor to the future Earl of Macclesfield, who acquired or copied many letters and papers relating to Newton’s early career. These formed the heart of the Macclesfield Collection, which has recently been purchased by Cambridge University Library. 31 rené descartes, Geometria ed. and trans. frans van schooten 2 parts (Amsterdam, 1659–61) 4o: -2 4, a-3t4, g-3g4; π2, -2 4, a-f4 Trinity* * College, Cambridge,* shelfmark* nq 16/203 Newton acquired this book ‘a little before Christmas’ 1664, having read an earlier edition of Descartes’ Geometry by van Schooten earlier in the year. -

Isaac Barrow

^be ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE S>et»otc^ to tbe Science of l^eUdion, tbe l^elfdfon ot Science, anb tbc BXiCnsion ot tbe Itelidioud parliament Ibea Founded by Edwabo C. Hegeuol VOL. XXX. (No. 2) FEBRUARY, 1916 NO. 717 CONTENTS: MM Frontispiece. Isaac Barrow. Isaac Barrow: The Drawer of Tangents. J. M. Child 65 ''Ati Orgy of Cant.'' Paul Carus 70 A Chippewa Tomahawk. An Indian Heirloom with a History (Illus- trated). W. Thornton Parker 80 War Topics. —In Reply to My Critics. Paul Carus 87 Portraits of Isaac Barrow 126 American Bahaism and Persia 126 A Correction 126 A Crucifix After Battle (With Illustration) ^ 128 ^be i^pen Court publiebing CompaniS i CHICAGO Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U.P.U., 5i. 6d). Entered w Secoad-QaM Matter March j6, 1897, at the Post Office at Chicago. III., under Act of Marck 3, \\j% Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Company, 1916 tTbe ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE S>et»otc^ to tbe Science ot l^eUdion, tbe l^elfdfon ot Science* anb tbe BXiCndion ot tbe 1{eliaiou0 parliament Ibea Founded by Edwabo C Hegeueb. VOL. XXX. (No. 2) FEBRUARY, 1916 NO. 717 CONTENTS: Frontispiece. Isaac Barrow. Isaa£ Barrow: The Drawer of Tangents. J. M. Child 65 ''A7i Orgy of Cant.'" Paul Carus 70 A Chippewa Totnahawk. An Indian Heirloom with a History (Illus- trated). W. Thornton Parker 80 War Topics. —In Reply to My Critics. Paul Carus 87 Portraits of Isaac Barrow • 126 American Bahaism and Persia 126 A Correction 126 A Crucifix After Battle (With Illustration) 128 ^be ®pen Court publisbino CompaniS I CHICAGO Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). -

The History of Newton' S Apple Tree

Contemporary Physics, 1998, volume 39, number 5, pages 377 ± 391 The history of Newton’s apple tree (Being an investigation of the story of Newton and the apple and the history of Newton’s apple tree and its propagation from the time of Newton to the present day) R. G. KEESING This article contains a brief introduction to Newton’s early life to put into context the subsequent events in this narrative. It is followed by a summary of accounts of Newton’s famous story of his discovery of universal gravitation which was occasioned by the fall of an apple in the year 1665/6. Evidence of Newton’s friendship with a prosperous Yorkshire family who planted an apple tree arbour in the early years of the eighteenth century to celebrate his discovery is presented. A considerable amount of new and unpublished pictorial and documentary material is included relating to a particular apple tree which grew in the garden of Woolsthorpe Manor (Newton’s birthplace) and which blew down in a storm before the year 1816. Evidence is then presented which describes how this tree was chosen to be the focus of Newton’s account. Details of the propagation of the apple tree growing in the garden at Woolsthorpe in the early part of the last century are then discussed, and the results of a dendrochronological study of two of these trees is presented. It is then pointed out that there is considerable evidence to show that the apple tree presently growing at Woolsthorpe and known as `Newton’s apple tree’ is in fact the same specimen which was identi®ed in the middle of the eighteenth century and which may now be 350 years old. -

Isaac Barrow on God, Geometry, and the Nature of Space Antoni Malet

Isaac Barrow on God, Geometry, and the Nature of Space Antoni Malet Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona INTRODUCTION Historians used to portray Isaac Barrow (1630-1677) as an obscure figure in Newton's background. He was a Janus-faced figure mainly of interest —one of his biographers once famously said— because he was “a link between the old and the new philosophy,” the old being his and the new Newton's.1 This theme became commonplace in dealing with Barrow. For decades, and with the exception of Barrow’s role in the philosophical articulation of the idea of absolute time, Barrow’s contributions were found to be hopelessly out of tune with contemporary modern intellectual tendencies. Consequently, attempts to trace any kind of substantial influence from Barrow on Newton always found an unsympathetic reception.2 The most important attempt to 1 P.H. Osmond, Isaac Barrow, His Life and Times (London: Soc. for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, 1944), p. 1. 2 Barrow’s articulation of the notion of absolute time is particularly well analyzed in E.A. Burtt’s old but still useful The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1989, first ed. 1924), p. 150-61. On Barrow’s notion of space, see E. Grant, Much ado about nothing. Theories of space and vacuum from the Middle Ages to the Scientific Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 236-238. See also E.W. Strong, 'Barrow and Newton', Journal of the History of Philosophy (1970), 8, 155-72; A. R. Hall, Henry More. -

The Geometrical Lectures of Isaac Barrow, Translated, with Notes And

Open Court Classics of Science and Philosophy, iOMETRICAL LECTURES OP ISAAC BARROW J. M, CHILD CO GEOMETRICAL LECTURES ISAAC BARROW Court Series of Classics of Science and Thilosophy, 3\(o. 3 THE GEOMETRICAL LECTURES OF ISAAC BARROW . HI TRANSLATED, WITH NOTES AND PROOFS, AND A DISCUSSION ON THE ADVANCE MADE THEREIN ON THE WORK OF HIS PREDECESSORS IN THE INFINITESIMAL CALCULUS BY B.A. (CANTAB.), B.Sc. (LOND.) 546664 CHICAGO AND LONDON. THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY 1916 Copyright in Great Britain under the Ad of 191 1 33 LECTI ONES Geometric^; In quibus (praffertim) GEHERALJA Cttr varum L iacaruw STMPTOUATA D E. C L A II 7^ A T^ T !(, Audore IsAACoBARRow Collegii S S. Trhiitatn in Acad. Cant ah. SociO, & Socictatif lie- ti< Sodale. Oi H< TO. <fvftt Aoj/r/ito; iruiv]<t nxSHfufla, at tr& wVi^C) o%*( OITTI a* i r>riu- GfetJfft , rttrv -mufAttli <iow it, yupi mt , *'Ao &.'> n$uw, O 6)f TO fi>1/Si' H tr;t ^urt^i oTi a'uT&i/yi'jrf **ir. Plato de Repub. VII. L ON D IN I, Cttlielmi Godkd & venales Typis , proftant apud OR.ivi.innm Jh-tnitf>t Tt-wmsre, & Pullejn Juniorcm. UW. D C L X X. " Note the absence of the usual words Habitae Cantabrigioe," which on the title-pages of his other works indicate that the latter were delivered as Lucasian Lectures. J. M. C. PREFACE ISAAC BARROW was Ike first inventor of the Infinitesimal Calculus ; Newton got the main idea of it from Barrow by personal communication ; and Leibniz also was in some measure indebted to Barrow's work, obtaining confirmation of his oivn original ideas, and suggestions for their further development, from the copy of JJarrow's book (hat he purchased in 1673. -

Introduction: 'Mind Almost Divine'

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66310-6 - From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University’s Lucasian Professors of Mathematics Edited by Kevin C. Knox and Richard Noakes Excerpt More information Introduction: ‘Mind almost divine’ Kevin C. Knox1 and Richard Noakes2 1Institute Archives, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 2Department of History of Philosophy of Science, Cambridge, UK Whosoever to the utmost of his finite capacity would see truth as it has actually existed in the mind of God from all eternity, he must study Mathematics more than Metaphysics. Nicholas Saunderson, The Elements of Algebra1 As we enter the twenty-first century it might be possible to imag- ine the world without Cambridge University’s Lucasian professors of mathematics. It is, however, impossible to imagine our world with- out their profound discoveries and inventions. Unquestionably, the work of the Lucasian professors has ‘revolutionized’ the way we think about and engage with the world: Newton has given us universal grav- itation and the calculus, Charles Babbage is touted as the ‘father of the computer’, Paul Dirac is revered for knitting together quantum mechanics and special relativity and Stephen Hawking has provided us with startling new theories about the origin and fate of the uni- verse. Indeed, Newton, Babbage, Dirac and Hawking have made the Lucasian professorship the most famous academic chair in the world. While these Lucasian professors have been deified and placed in the pantheon of scientific immortals, eponymity testifies to the eminence of the chair’s other occupants. Accompanying ‘Newton’s laws of motion’, ‘Babbage’s principle’ of political economy, the ‘Dirac delta function’ and ‘Hawking radiation’, we have, among other things, From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University’s Lucasian Professors of Math- ematics, ed. -

Hobbes on Natural Philosophy As “True Physics” and Mixed Mathematics

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Philosophy Faculty Scholarship Philosophy 2016 Hobbes on Natural Philosophy as “True Physics” and Mixed Mathematics Marcus P. Adams University at Albany, State University of New York, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/cas_philosophy_scholar Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Marcus P., "Hobbes on Natural Philosophy as “True Physics” and Mixed Mathematics" (2016). Philosophy Faculty Scholarship. 12. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/cas_philosophy_scholar/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hobbes on Natural Philosophy as “True Physics” and Mixed Mathematics Marcus P. Adams Department of Philosophy University at Albany, SUNY Email: [email protected] Web: https://marcuspadams.wordpress.com/ Forthcoming in Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. This is an author’s pre-print; please cite the published version. The published version is available at the Studies in History and Philosophy of Science (Elsevier) website: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0039368115001600 Hobbes on Natural Philosophy as “True Physics” and Mixed Mathematics [...] physics (I mean true physics), that depends on geometry, is usually numbered among the mixed mathematics. De homine 10.5 (Hobbes 1994) [...] all the sciences would have been mathematical had not their authors asserted more than they were able to prove; indeed, it is because of the temerity and the ignorance of writers on physics and morals that geometry and arithmetic are the only mathematical ones. -

Toward a New Heaven and a New Earth: the Scientific Revolution and the Emergence of Modern Science

CHAPTER 16 Toward a New Heaven and a New Earth: The Scientific Revolution CHAPTER OUTLINE • Background to the Scientific Revolution and the • Toward a New Heaven: A Revolution in Astronomy • Advances in Medicine • Women in the Origins of Modern Science Emergence of • Toward a New Earth: Descartes, Rationalism, and a New View of Humankind Modern • The Scientific Method • Science and Religion in the Seventeenth Century • The Spread of Scientific Knowledge Science • Conclusion FOCUS QUESTIONS L • What developments during the Middle Ages and Renaissance contributed to the Scientific Revolution of the seventeenth century? • What did Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton contribute to a new vision of the universe, and how did it differ from the Ptolemaic conception of the universe? • What role did women play in the Scientific Revolution? • What problems did the Scientific Revolution present for organized religion, and how did both the church and the emerging scientists attempt to solve these problems? • How were the ideas of the Scientific Revolution disseminated, and what impact did they have on society? N ADDITION to the political, economic, social, and international crises of the seventeenth century, we need to add an intellectual Ione. The Scientific Revolution questioned and ultimately challenged conceptions and beliefs about the nature of the external world and real- ity that had crystallized into a rather strict orthodoxy by the Late Mid- dle Ages. Derived from the works of ancient Greeks and Romans and grounded in Christian thought, the medieval worldview had become a formidable one. No doubt, the breakdown of Christian unity during the Reformation and the subsequent religious wars had created an environ- ment in which Europeans had become accustomed to challenging both 460 the ecclesiastical and political realms. -

228 Mordechai Feingold. the Newtonian Moment

228 SEVENTEENTH -CENTURY NEWS Mordechai Feingold. The Newtonian Moment: Isaac Newton and the Making of Modern Culture. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. xv + 215 pp. $22.50. Review by IRV I NG A. KELTER , UN I VERS I TY OF ST. THOM A S , HOUSTON . Sir Isaac Newton was a towering figure in seventeenth-century English science and culture and, indeed, in the development of all of modern Western culture. The book under review by Dr. More- dechai Feingold, the well-known historian of early modern English mathematics and science, was a companion volume to the wonderful exhibition on Isaac Newton and his influence which ran at the New York Public Library form October 8, 2004 until February 5, 2005. This reviewer was lucky enough to view this splendid exhibition at the New York Public Library. The first chapter, “The Apprenticeship of Genius,” takes the reader through Newton’s early years, his education, his relations with teachers and fellow scientists such as Isaac Barrow and Robert Hooke, and ends with the publication of the Principia in 1687. Chap- ter Two, “The Lion’s Claws,” begins the discussion of the reception of Newton’s work with reactions of supporters such as Halley and Locke and critics such as Huygens and Leibniz. This chapter also details the appearance of Newton’s Opticks (1704) and the beginnings of the fierce priority dispute between Newton and Leibniz over the invention of calculus. Chapters Three and Four, “Trial By Fire” and “The Voltaire Ef- fect,” cover the reception of Newton’s Principia and Opticks on the continent and the struggle against rival views, especially Cartesianism. -

Mathematicians Timeline

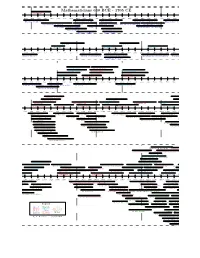

Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold Sergey Bernstein Gotthold Eisenstein Edmund Landau Issai Schur Leoplod Kronecker Paul Halmos Hermann Minkowski Hermann von Helmholtz Paul Erd}os Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Vladimir Steklov Karl Weierstrass Kurt G¨odel Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Andrei Markov Ernst Eduard Kummer Alexander Grothendieck Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Sofia Kovalevskya Andrey Kolmogorov Moritz Stern Friedrich Hirzebruch Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Georg Cantor Carl Goldschmidt Ferdinand von Lindemann Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Pafnuti Chebyshev Oscar Zariski Carl Gustav Jacobi F Georg Frobenius Peter Lax Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Solomon Lefschetz Julius Pl¨ucker Hermann Weyl Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Karl von Staudt Eugene Wigner Martin Ohm Emil Artin Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold August Ferdinand -

Orozco-Echeverri2020.Pdf (3.437Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. How do planets find their way? Laws of nature and the transformations of knowledge in the Scientific Revolution Sergio Orozco-Echeverri Doctor of Philosophy in Science and Technology Studies University of Edinburgh 2019 To Uğur In his own handwriting, he set down a concise synthesis of the studies by Monk Hermann, which he left José Arcadio so that he would be able to make use of the astrolabe, the compass, and the sextant. José Arcadio Buendía spent the long months of the rainy season shut up in a small room that he had built in the rear of the house so that no one would disturb his experiments. Having completely abandoned his domestic obligations, he spent entire nights in the courtyard watching the course of the stars and he almost contracted sunstroke from trying to establish an exact method to ascertain noon.